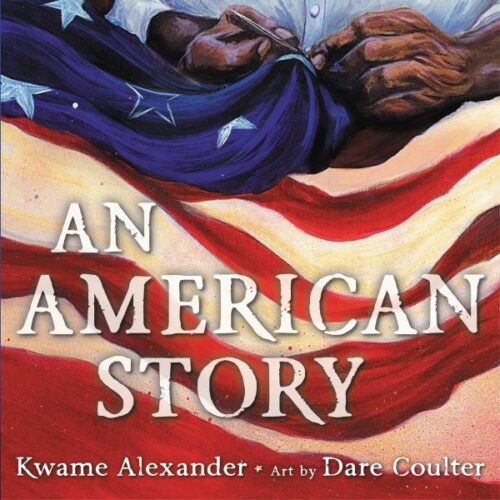

Review of the Day: An American Story by Kwame Alexander, ill. Dare Coulter

An American Story

By Kwame Alexander

Illustrated by Dare Coulter

Little, Brown and Company

$18.99

ISBN: 978-0-316-47312-5

Ages 7 and up

On shelves now

How soon is too soon? How early is too early? Is it possible to teach the hard parts of American history (putting back in all the people who were left out of our history books when we were kids) to children of a young age? I’m not just saying this off the top of my head, because all across this nation right now this debate is raging, sometimes literally. Changing anything about education is going to meet with resistance, sure. That said, there seems to be a very specific thoughtless objection out there to the notion that children should learn from the get-go that, for much of our history, America hasn’t been all that great for large swaths of the population. The fear, I suspect, is rooted in an understanding that by showing the mistakes of the past, children will be less inclined to show mindless nationalism at a drop of a hat. There is also a fear, and this often baffles me, that by learning about historical facts like slavery, white children will “feel bad”. Both of these possibilities sort of baffle me, but the latter is particularly out there. They’ll feel bad. I mean . . . great! They should! These were bad things that happened! I don’t think I want anyone coming away from that feeling cheery. Kwame Alexander knows that. He discovered that his daughter’s fourth grade class was learning about life in the thirteen colonies without any mention of “the impact and trauma of slavery”. When confronted, the teacher was defensive and distressed because, Kwame surmised, she was never taught how to teach the subject. An American Story (the title is key) is his answer to that problem. Pairing with miraculous, marvelous artist Dare Coulter, Kwame tackles this subject matter head on, providing a template not just for teachers, but for any adult wishing to give the kids of today a better grasp on material that so many have worked so hard to avoid for all these years.

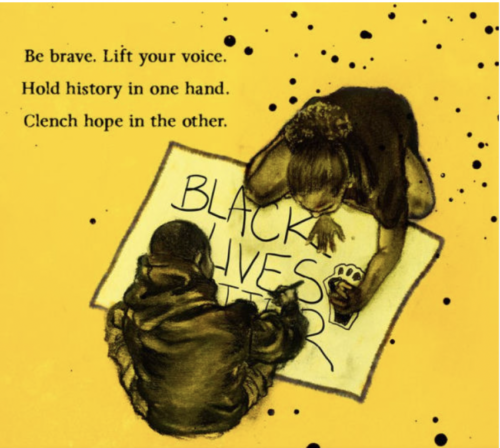

“How do you tell a story that starts in Africa and ends in horror?” It’s a fair question. Readers watch as people on African shores live their lives, tell their stories, and dream. Turn the page and all you see are hands, shackled. Lives uprooted. But then the narrative shifts and we see another shot of hands. These are the hands of kids in a classroom today. Occasionally, throughout the book, you hear their words. “But you can’t sell people,” they say. We watch hard things, like people jumping off the slave boats to their death in the sea. We see an enslaved boy picking cotton and, on the other page, a little white boy playing and reading a book at the same time. We see the people that were stolen finding joy where they can, but we also see then wading through waters and running at night to escape. We see children taken from their mamas. And then the book says, “I don’t think I can continue. It’s just too painful. I shouldn’t have read this to you. I’m so sorry, children.” It’s present day, and the students object. They know it’s hard but they also know it’s important. Because this American story is, “About yesterday’s nightmare and the courage to dream a new tomorrow.” And as the book says, you deal with this information, “by being brave enough to lift your voice, by holding history in one hand and clenching hope in the other.”

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

“An American Story” isn’t the first book along these lines to exist, necessarily. For example, just two years ago we saw the beautiful 1619 Project: Born on the Water by Nikole Hannah-Jones and Renée Watson (illustrated by Nikkolas Smith) cover much the same ground. Like this book, it took time to show the people that would later be enslaved first living their lives fully, long before they were in chains. Like this book it draws some connections to the children living today here in the States, but in terms of the storytelling, Kwame introduces a specific element into this book that I haven’t seen used very often before. As I mentioned before, periodically, as the difficult material comes to the fore, we cut to a contemporary classroom of kids, raising their hands, asking questions. These sections are particularly interesting because these kids do NOT look happy to be learning this information. But as you go through it, the teacher who is reading this information to the class is the one who wants to stop, not the kids. The kids call her on it. They say, “But don’t you tell us to always speak the truth, Ms. Simmons, even when it’s hard?” That’s a theme I’m seeing come up more and more in my books for kids. The easy thing and the right thing are not often the same thing.

I want to talk about a key element of this story that shows how far we’ve come since 2016. I’ve picked that date specifically because almost exactly seven years before this book was published, there was another book that discussed slavery in some way. A Birthday Cake for George Washington is one of the few American children’s books ever pulled from publication mere days after it hit shelves, due to a public outcry. The outcry was not from people objecting to slavery being featured in a picture book, in the same way that we’re seeing it today. Rather, the outcry was about the way in which the enslaved were depicted. The term “smiling slaves” came up many times, because if you read through the book you came away from it with the distinct impression that the enslaved didn’t really mind being forced to work for George Washington’s family. That they were happy about it. The book was released close on the heels of another book called A Fine Dessert which also featured what was dubbed the “smiling slaves” trope, and though one was a bit more egregious in its depictions than the other, it could be fair to say that context was missing from the latter. Now we fast forward to 2023 and Kwame Alexander, I think we can all agree, is aware of that bit of recent history. Fully and completely aware of what was said at that time. But for him, it’s important to show something more than despair. He writes, “How do you tell a story about strength and pride and refusing to be broken and refusing to stop smiling and loving…” And then, on the page, we see enslaved people in the night, gathering together, smiling in the moonlight. And I think the key here is Kwame’s intent. He’s filling this book with historical horrors while at the same time making it clear repeatedly that these were real people who went through all of this. And real people smile, and those smiles belong to themselves and themselves alone. There’s been a big push for more children’s books to show Black joy on the page, and not just trauma. Kwame is determined to include both in a single book, making it complicated and interesting and human. After all, in one of the shots of a man smiling, holding his children, you can easily see the cuts and scars on his arms where injury was inflicted upon him not too long ago.

The fact that I’ve gotten this far into this review and I haven’t said boo about the art is as egregious as it is a testament to the writing and subject matter. Now I need to give a little context to what I experienced as I read this book. Do any of you reading this suffer from a knee-jerk reaction to stuff you’re told you have to like? I swear, if someone or something gets too big or too much attention, and I haven’t read or seen it yet, I’m already biased against it. I just am! And I’ve liked Kwame’s books over the years just fine, but y’know,, he’s got a reality show and he just keeps on cranking out these award winning books. So here I am picking this book up and I see the cover and think immediately that there’s no way I’m going to like this more than the aforementioned Born on the Water. And indeed, the first two, three, four, five, six or so pages are convincing me otherwise. I don’t know Dare Coulter’s work, but the initial images in the book are built to start slow. She’s keeping the visual storytelling on a low boil in those first few pages, and I admit, it completely fooled me. Then I got to the page turn that reveals two girls playing in front of a fire while a storyteller stands behind them. I stare and I stare and I stare at these pages, trying to make sense of what I’m seeing because suddenly these painted pages have taken on weight and depth that they didn’t have before. What I’m seeing isn’t two-dimensional. This is modelwork and lighting and who knows what all. It is at this moment that I stopped being so silly about whether or not I should be so critical of this book that’s already acquired five stars from from review journals. There’s something going on here, and it’s something I’ve never before.

Flip to the back of the book and you’ll learn that Dare Coulter, a self-described painter, sculptor, and muralist, has created this book “with a combination of spray paint, acrylic paint, charcoal, graphite, ink, and digital painting on wood panel and watercolor paper,” while the sculptures, “are both ceramic and polymer clay with added materials.” Lest you think her work has come out of the blue, Coulter has done a number of picture books in the past. The bulk of them were published independently (though she did do one for the North Carolina Office of Archives and History), and none of them look like this book. The difference may lay, in large part, in these sculptures. On her website Dare writes, “In my opinion my sculptures are the most important thing that I create.” So to find a project where that love could be integrated with the text, that is one of the many keys to this book’s success. But it isn’t just that the sculpture work pops up periodically in the book. Oftentimes it’s seamlessly integrated alongside the illustrations. There’s an early shot of a young man lying on his back, where his body is modeled, but somewhere between the grasses he’s lying on and the fabric wrapped around his waist, it becomes illustration again. After a while, you realize that the past morphs between sculptures and illustrations seamlessly over and over again. The present, however, is portrayed as a shock of yellow paper with drawings of contemporary kids that look like they were sketched in charcoal. This gives the necessary contrast you need between the past and the present, and sets us up for that last two-page spread that bridges the two.

You know how else I can tell that this is not Ms. Coulter’s first book? The page turns. Kwame’s enough of an expert in the field that I’m sure when he wrote the book he knew exactly where each turn would hit. But what he could not have anticipated was how Dare Coulter would create emotional beats with those turns all on her own. For example, there’s a shot early on of a girl in a contemporary classroom looking particularly sad about what she’s hearing. If you turn the page you’re in the past again and sitting there, staring right at you, is a girl around the same age, holding someone’s crying baby at night. It’s not just the page turns, though. The way in which Ms. Coulter can pair the pages together requires an entirely different set of muscles. Two shots, different locations, from above of people attempting to escape are followed not long after by two shots of two boys of the same age, one from the past with a rope about his neck and a boy of today staring into space. Ms. Coulter is inviting you to make these comparisons. To flip back and forth throughout the book finding the things you missed the first time, or to just stare at what’s in front of you and take it in.

After a third or fourth read of this book, I realized that you could, potentially, make this book a class readaloud. What if a teacher read the parts about the history, and the contemporary pages of kids today was read by kids in a classroom? It could work. It could fail too. It would be a risk. In some parts of the country, reading this book in a classroom at all would be considered a risk for some teachers. Some people wouldn’t even attempt to give it an initial try, and those are the cases when you want people to do the right thing. As last year’s nonfiction picture book Choosing Brave said about Mamie Till-Mobley, sometimes in this life you have to decide whether or not to do the easy thing or the right thing. This book… it helps teachers, parents, educators, all of us, to do the right thing. To teach our kids An American Story that they won’t find in most of their textbooks. Because you know what happens when you teach children about the truth of history? You might make them sad, yeah. But they’ll learn and maybe, thanks to books like this one, they might even remember. All it takes, is the attempt.

On shelves now.

Source: Galley sent from publisher for review.

Interviews: You can read this interview with Kwame and Dare about the book here at SLJ.

You can also hear Kwame and Dare talking together, as they are interviewed at News 4 Jax (of Jacksonville, Florida) on their Morning Show here. Dare even shows one of the sculptures from the book.

Filed under: Best Books, Best Books of 2023, Reviews, Reviews 2023

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

One Star Review, Guess Who? (#202)

More Geronimo Stilton Graphic Novels Coming from Papercutz | News

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

Take Five: LGBTQIA+ Middle Grade Novels

ADVERTISEMENT

Betsy, I don’t know if you’re familiar with the Great Blacks in Wax Museum of Baltimore, but the minute you said “sculpture,” I realized that that’s what this book reminds me of. I wonder if Dare Coulter’s visited it.

Perfect review of this amazing book, Betsy. It is hard in January to talk about the Caldecott, but Dare Coulter has to be in that conversation for 2023.