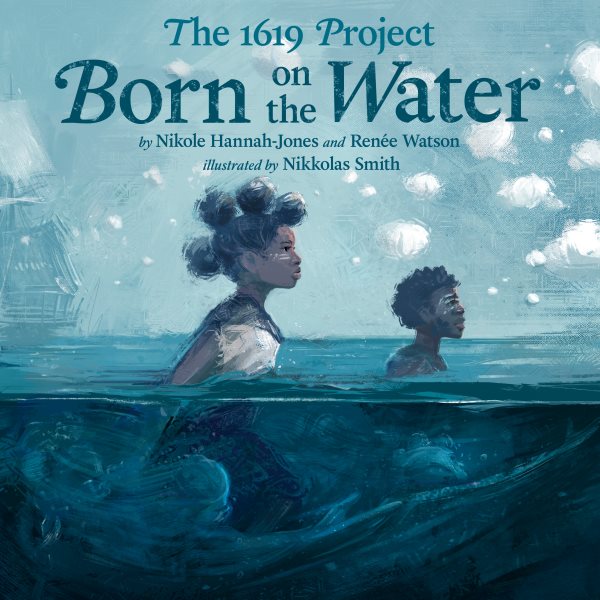

Review of the Day – The 1619 Project: Born on the Water by Nikole Hannah-Jones & Renée Watson, ill. Nikkolas Smith

The 1619 Project: Born on the Water

By Nikole Hannah-Jones & Renée Watson

Illustrated by Nikkolas Smith

Kokila (an imprint of Penguin Random House)

$18.99

ISBN: 9780593307359

On shelves November 16th

For as long as authors of books for children have determined that they should be open and honest with their young readers, they have struggled with how much trauma is appropriate. You hear this debate a lot as it pertains to the Holocaust. Should we put it in books? How often? How young should readers be to hear about it? How young is too young? There are strong opinions but no clear-cut answers. The same could be said about slavery in America. But for too long, the Black American history taught in schools has hooked its beginnings on the existence of slavery. Meanwhile the books kids were given to read with Black characters tended to rely on trauma and misery. It’s only been recently that the concept of #blackjoy, and handing kids books that star Black characters but aren’t all slavery or Civil Rights titles, has entered the mainstream vocabulary. And I want to be clear that yes, there is slavery in The 1619 Project: Born on the Water, but like this year’s surprisingly good Timelines From Black History: Leaders, Legends, Legacies, this book begins long before that slavery took place. “Their story does not begin with whips and chains,” says the book. And poetry, at least this poetry, doesn’t lie.

Author Nikole Hannah-Jones and Renée Watson says in their Author’s Note that the intention here was to, “show that Black Americans have their own proud origin story, one that does not begin in slavery, in struggle, and in strife but that bridges the gap between Africa and the United States of America. We begin this book with the rich cultures of West Africa and then weave the tale of how after the Middle Passage, Black Americans created a new people here on this land.” And so our story starts with a Black girl in school being given an assignment to trace her roots and “Draw a flag that represents your ancestral land.” The girl is stumped. While the white kids around her are bragging on how many generations they have, she feels ashamed that she can only count back three. When she mentions this to her grandmother, Grandma gathers the whole family and begins to tell a story. She doesn’t begin in slavery, though. She begins before 1619 and the ship White Lion that brought slaves before even The Mayflower. She relates times in the Kingdom of Ndongo where the people, “knew the power of a seed, how to plant it, water it, how to make something out of nothing.” And yes, slavery took their ancestors. But the way she tells it you realize that this is a much bigger, more complicated story than the ones they teach the kids in school. Best of all, it leaves kids, just like the main character, holding up their heads with pride.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Like other librarians I was more familiar with Renée Watson and her work than I was with Nikole Hannah-Jones. That is, until I realized that this was the same Nikole Hannah-Jones that declined a tenure offer at University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, accepting a Knight Chair Appointment at Howard University. What’s more, she’s the creator of the 1619 Project itself. Collaborator Renée Watson, on the other hand, has vast experience writing children’s and YA materials in a variety of different forms and formats. Whether it’s the picture book biography of Florence Mills (Harlem’s Little Blackbird), early chapter book series (the Ryan Hart, stories), fictionalized biographies (Betty Before X), realistic contemporary middle grades (Some Places More Than Others), multiple anthologies or YA novels, she has this vast range. She’d never really done historical poetry before, but after reading this book you can see how well she adapts to new styles.

So why poetry? Why use that particular form to tell this story? I’m always intrigued by an author’s choice to turn a book into verse. There are times that this choice feels off-handed and superficially stylistic. This is most often the case when you half suspect the designer of the book reset the typeface and rearranged the book so that it looks like verse, just so that they could fill space. Not so here. Since this is Grandma’s story in Grandma’s voice, you need a clear delineation between the present and the past. Poetry provides that important break, but has other functions as well. For example, look at how repetition in the book is key. Notice how Watson uses that repetition on lines like, “They spoke Kimbundu, had their own words”. There are others too. “We are in a strange land … But we are here and we will make this home.” It’s a chant. Thanks to poetry, the child reader finds a comfort in the repeated lines, both before and after the traumatizing events. More to the point, the repetition in the second half of the book harkens back to the repetition in the first half, making it clear that the people who have been stolen are carrying with them things from home that cannot be carried anywhere but inside.

The book also goes right for the jugular. Talking about the moment when the people were stolen the text reads that, “They did not get to pack bags stuffed with cherished things, with the doll grandmamma had woven from tall grass…” Watch how artist Nikkolas Smith renders the village, empty and destroyed, one doll woven from grass tied to a tree alone. “Ours is no immigration story.” This story does not begin with slavery because if you start with slavery then you have no sense of what has been lost. Roots knew this. Kids books have a tendency to forget.

Now I would love to hear the story of how artist Nikkolas Smith was added to this project. Out of curiosity I took a look at his website and what I saw there was this jaw-dropping range of styles to rival Renée Watson herself . The man is just as comfortable rendering an image with Pixar-level smoothness as he is the broad, thick brush strokes of paint you’d find in any Impressionist painting. Yet when it comes to books for kids, it feels as though he’s been reigning himself in. This isn’t uncommon amongst fine artists making the transition to picture books. Too often they dumb down their style or iron out whatever it is that makes them unique. This in spite of the fact that if they embrace the bookmaking process with the same vigor they do their art, they could end up with a multi-award winner like Gordon C. James’s work on Crown: An Ode to the Fresh Cut. Fortunately, somewhere between his first few books and Born on the Water a switch was flipped. These paints are unrestrained, the brush strokes thick, plentiful, and beautiful. In his Note at the back of the book he credits Central West Africa for the details in architecture, hair, instruments, clothing, and more he chose to include. He uses “African scarification pattern motifs, where Life, Death, and Rebirth are present.” But on top of all that, on top of the sheer beauty of the paint itself, he knows how to render laughter. Sometimes I think laughter that looks like laughter must be the most difficult thing an artist can create. Not so for Mr. Smith. He can do misery and cruelty and pain as well as anyone else, but he does full-throated joy just as well. Not everyone is so talented.

A person could take a much deeper dive into the art than I have here. The endpapers alone are worth a ten-minute discussion, after all. There’s a lot more to say about the text too. We could discuss how this whole endeavor could easily have tipped sideways. How countless books with good intentions have sunk under the weight of their material, rendering their subject matter flat and, in spite of the content, uninteresting to kids. This book, I believe kids will like. Effort has been put into the text, and the framing sequence (a class assignment that more than one kid will recognize from their own life) is a brilliant way to couch this. This book is clever and gutting and gorgeous. And here’s the highest compliment of all: I truly believe that a kid, on their own, would read this multiple times. It’s a marvelous testament to not just the power of reclaiming your own story, but the story of your ancestors as well. A rarity deserving of discovery.

On shelves November 16th

Source: E-galley from publisher

Filed under: Best Books, Best Books of 2021, Reviews, Reviews 2021

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Name That LEGO Book Cover! (#53)

K is in Trouble | Review

Fighting Public School Book Bans with the Civil Rights Act

ADVERTISEMENT