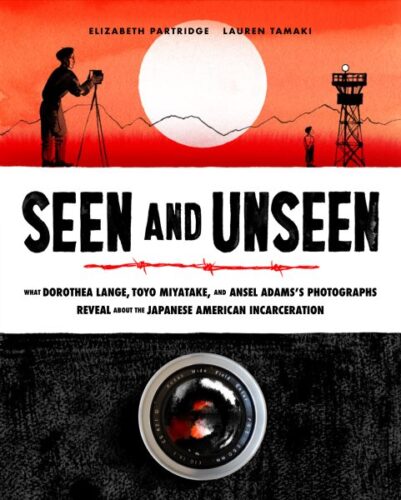

Review of the Day: Seen and Unseen by Elizabeth Partridge, ill. Lauren Tamaki

Seen and Unseen: What Dorothea Lange, Toyo Miyatake, and Ansel Adams’s Photographs Reveal About the Japanese American Incarceration

By Elizabeth Partridge

Illustrated by Lauren Tamaki

Chronicle Books

$21.99

ISBN: 9781452165103

Ages 9-12

On shelves October 25th

My son is very into asking hard questions these days. He’s eight and has discovered the beauty of putting adults on the spot with a hard-hitting query. “What’s your greatest regret?” he might ask one day. Or “What was the best day of your life?” Very into superlatives my son. It isn’t all personal, though. We might be discussing politics at the dinner table when he’ll suddenly interject with, “Who was the greatest president of all time?” And we all have our favorites but most of the time FDR rises to the top. Now here’s where it becomes a little more difficult to be a parent in the early part of the 21st century. You can’t just say FDR was the greatest president, full stop. Sometimes (often) a little nuance is in order. So you could list all the good things that FDR did and then couch that with some complexity. “He was great, but he wasn’t perfect. He did some awful things.” And when the child asks for clarification (which they will) that’s when you get into the subject of the incarceration of the Japanese and Japanese Americans living on the West Coast of the U.S. If you want to really take a deep dive into the subject there are a lot of different children’s books you can use. Want middle grade fiction? Try Weedflower by Cynthia Kadohata. A graphic novel more your speed? Stealing Home by J. Torres works well. For the younger end of the scale, as in a picture book form, you could do Love in the Library by Maggie Tokuda-Hall. But I think that for a long time from now, the book I’m going to keep coming back to will be Elizabeth Partridge and Lauren Tamaki’s Seen and Unseen. Not only does it show the incarceration camps for what they were but it also offers a clever lesson on how the media is able to frame, crop, and generally direct the images we see in our news and that manipulates our opinions. By taking three photographers that shot the camps in three different ways, we get a well-rounded portrait of a government desperate to sell a bad idea to the American public under the guise of openness.

On December 7, 1941 the Japanese bombed a U.S. Navy Base at Pearl Harbor in Hawai’i. On February 19, 1942 President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued the removal of 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry from the West Coast. It took that little time. In Seen and Unseen we follow three photographers that captured images of the detention centers where American citizens were interred. The first of these was Dorothea Lange, who was horrified by the government’s plan and decided to take photos that would show what was happening to the people. When she turned in her images, Major Beasley at the army’s Western Defense Command disliked any shot that truthfully showed the harsh conditions suffered by the imprisoned. As a result, many images were impounded until long after the war. The second photographer was Toyo Miyatake, imprisoned himself from 1942-1945, who was able to smuggle in film and other supplies. To this day the most accurate images from inside the camps are attributed to him. Finally, the last photographer was Ansel Adams, a man uninterested in showing things as bleak. Whenever possible he showed things as happy, people in the camps working hard, living their best lives. While his intentions were to show to white Americans that Japanese Americans were trustworthy and patriotic, his photos told a lie of the lives they were forced to lead. Copious backmatter shows the aftermath of the camps, sections on civil liberties and the constitution, further info on the photographers and creators of this book, and a keen two-page breakdown of “the model minority myth” by artist Lauren Tamaki.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

I was a photography major in college and I never quite lost my love of the format. My ache for it comes and goes over the years, but this book really reminded me why I love this art more than so many others. Elizabeth Partridge is, herself, the goddaughter of Dorothea Lange, which lends a certain personal aspect to the book. Though many children’s books utilize photography in some capacity, few of them give such a clear cut understanding of why photos can be an important tool when fighting injustice. Not that Partridge is drumming that message into anybody’s head. “Show don’t tell” is the name of the game here. She lets the facts and photos bear the bulk of the burden. And as the premise of the book is to show why they were so dire, not simply to us today but to the government and the people then, you can’t walk away from this and not be aware of the impact of how you (literally) frame the truth.

Partridge’s choice to focus on the three photographers in particular is keen, and it’s interesting to work out her process. She structures the book with Lange first, Miyatake second, and Adams third. I think she went with chronology as her guide. Certainly, if that wasn’t a factor, you might want to switch it up a bit. Place the put-on-a-happy-face Adams first, Lange with her gimlet eye second, and the pure truth of Miyatake third. But the way it currently stands works too. With Lange first you start with how these camps came to be, and Lange’s fury with them right from the start. Then you cut to what it’s like inside the camps and Miyatake’s work there. Ending with Ansel Adams feels like backtracking but has everything to do with not simply how the government was trying to sell this situation to the American public, but also how history was in danger of doing the same. Without Lange and Miyatake, the Adams photographs could remain dangerously unchallenged.

Which makes it all the more impressive that Lauren Tamaki was brought on to this project. Partridge has produced photo-centric books before, all to the good. But to the best of my knowledge this kind of illustrated, photographic mash-up is new to her. At an initial glance I figured the illustrations would simply fill in the gaps where photographs could not go. The bulk of Toyo Miyatake’s incarceration, for example, would be a prime time to do so. But the art is much cleverer than that. It fills the book, giving it a graphic novel feel. More to the point, it incorporates actual photographs into the images. A drawing of Toyo Miyatake photographs a photo of a man and woman in his studio. A horrific racist drawing of a “Jap” hangs on a street, the watercolors of Japanese-Americans averting their eyes. Ms. Tamaki’s use of color is also particularly interesting. In the sequence where film is smuggled into the camps to Miyatake, the sole source of color is a man’s coat. When the supplies are removed from the coat and Miyatake gazes at them in his hands, there’s just the faintest echo of the reddish-peach color there. Turn the page and now that color has been amplified into a gorgeous sky, as Miyatake takes a few photographs in the early morning light. There is such care and attention paid to when and where Tamaki punctuates a page with her art. Every last leaf of this book has been strategically designed by Tamaki and Lydia Ortiz, and the sheer amount of work results in something folks sometimes forget about when they review books for kids: A kid would actually want to read this. I’m serious! Any kid into graphic novels and comics is going to fall naturally into reading this factual history. The transition is almost seamless.

All of this reminds me of an interesting debate that surrounds illustrated nonfiction for children. Some of us (guilty party here) spend a lot of time speculating about truth in works of biography. For example, to include fake dialogue within quotation marks implies that someone actually said those words, so that’s no good. Likewise merging real people together or mucking with the facts is frowned upon. But what about illustrations? We cannot for certain say that this man stood at this angle and leaned his body in this particular way at this point in history, can we? All this means that Ms. Tamaki must often walk a fine line between fact and fiction. We cannot say that this particular woman passed a racist sign and then wiped her eyes with the back of her hand, but since the book does not precisely say who this woman was, we can extrapolate that she represents the many women who did exactly that. The people waiting in line, huddled under umbrellas, or lying in the shade of a building on a hot day, they existed. Maybe not at that exact moment but the truth lies in the representation if not the exactitude of the moment. As such, I’d say that this book is wholly factual, from its art to its photography, to its writing.

This year, some of my colleagues and I came to a new realization about backmatter in children’s books. Simply put, if the backmatter is better than the main text, more interesting or more nuanced or simply contains the facts you wish you’d seen in the story itself, that’s a problem. Here? Not a problem. That said, the backmatter is absolutely fascinating. We’ve come a long way from the days when nonfiction for kids could just throw a bunch of suppositions together and call it a day. Here, Partridge and Tamaki have split the backmatter into eleven different sections. There’s “After the War”, “Why Words Matter”, “Citizenship Violated”, “Civil Liberties and the Constitution,” “Keeping Our Democracy Strong,” bios of the three photographers, an Author’s Note (accompanied by a photo that I suspect is of Partridge as a kid with Lange), an Illustrator’s Note, “The Damage of the Model Minority Myth”, Notes, and Photo Credits. Each one highlights a different aspect of the book itself. I was particularly taken with “Why Words Matter” which explains how the U.S. government used language to downplay what it did to the incarcerated Japanese and Japanese-Americans. The book mentions that the words used in this book (“forced removal”, “detention centers”, “inmates”, “prisoners”, and “concentration camps”) are more accurate than many of the terms you usually hear about this time. It explains as well why “concentration camps”, though it may initially sound overly harsh, is the more accurate phrase here.

I am writing this review at a time in our country where any books that present American history through anything less than rose-colored glasses are, by some people, considered supremely suspect. I have no doubt at all in my mind that there are book banners around the U.S. that would very much like to keep this book out of the hands of children. In spite of that fact, have you considered at all how lucky our kids are right now? We live at a time when writers and illustrators for children are, by and large, inclined to tell children the truth about history. About mistakes made and how we need to learn from them when going into the future. As books about this moment in history go, Seen and Unseen has gotta be one of the most enjoyable I’ve ever encountered. Not that the subject matter is dappled in sunlight or anything, but it’s just a pleasure to read. The mix of illustration and photography is expertly done, the text never thick and dull. You are sucked into Partridge’s telling and Tamaki’s art from the get go. And if a couple kids become interested in how visual images are used by governments to sway or by citizens to reveal, all to the good. History, photography, comic art, and a distinctly contemporary take on telling kids the truth about the past. What could be better?

On shelves October 25th

Filed under: Best Books, Best Books of 2022, Reviews, Reviews 2022

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Name That LEGO Book Cover! (#53)

Exclusive: Vol. 2 of The Weirn Books Is Coming in October | News

Fighting Public School Book Bans with the Civil Rights Act

Take Five: Middle Grade Anthologies and Short Story Collections

ADVERTISEMENT

Thank you, Betsy for your poignant review of this book illuminating the truths of a time in history that we mustn’t keep in the dark. It is timely now and is needed for children and adults alike to be aware of the whole history of the past so we may do better, be better present day and onward. Children deserve examples of truth in its entirety, not just versions of truths that may be more comfortable to absorb. Children are capable of openness, goodness, and compassion. They are our hope for humanity. We must inform them of the past, learn from our mistakes and empower them with the knowledge they need to be a part of the change we desperately need.

As someone who experienced loss of home, loss of country and the isolation of living at a refugee camp for six months uncertain of our new life in America, I felt each and every one of your words. Vietnamese Americans also carry the burden of a complicated history. Though our history is intertwined with the American people, we too have been shamed into believing that our history about the Vietnam War, though complicated, doesn’t deserve to be acknowledged. Some members of the press and journalists during that era also chose to paint a less than accurate picture of our experiences—one that shares half truths. I’m grateful to add my voice, my words, and my stories to Vietnamese Americans who are telling their stories or that of their family who came before them. We have a responsibility to share our narrative from our lived experiences. I’m honored to share stories inspired by my Vietnamese heritage and refugee experiences from the lenses of my eight years old self. I want children to be aware of the goodness that existed even in the midst of war and the challenges of starting over in uncharted territory.

I’m grateful for the important work you’re doing to help us share our stories authentically and lift up voices that echo and honor the complexities of our shared history.

I look forward to reading this book. I would like to add some thoughts about FDR; I agree with you that he was one of our greatest presidents. Nevertheless, he failed in several ways, one of which was his executive order depriving Japanese Americans of their most basic rights. FDR’s insistence on placating southern Democrats was one of the reasons for his dismal record on race. He allowed Black Americans to be effectively excluded from many New Deal programs and would not desegregate the armed forces. Finally, his appalling refusal to respond in any meaningful way to the Holocaust is one of his worst failures. He ignored pleas for changing immigration restrictions, nor would he consider specific military responses to the slaughter of Europe’s Jews. I fear that readers, even some who know about the Japanese American internment camps, may not be aware of how he turned his back on victims of Nazi extermination camps. Finally, although I don’t categorically object to the use of the term “concentration camp” to describe the unlawful and cruel imprisonment of Japanese Americans, there are legitimate issues to raise about it. Although the term pre-dates the Holocaust, some would argue that its connotation as places where Nazis murdered, tortured, and starved Jews (as well as other people), has now replaced its previous definition.