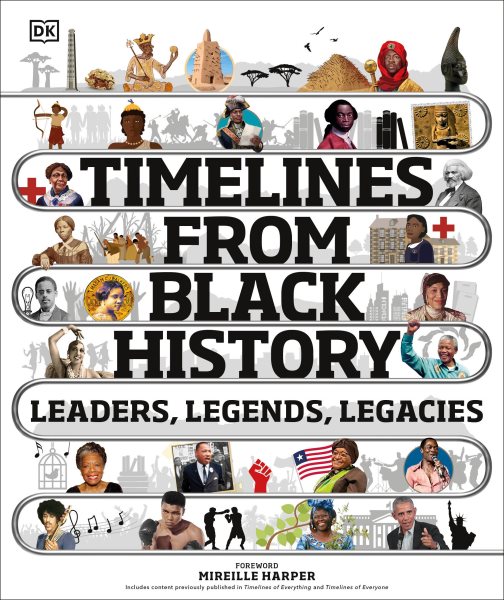

Review of the Day: Timelines From Black History: Leaders, Legends, Legacies by D.K. Publishing

Timeline From Black History: Leaders, Legends, Legacies

Edited Steven Carton

D.K. Publishing (a division of Penguin Random House)

$19.99

ISBN: 9780-7440-3909-2

Ages 9-12

On shelves now.

In the course of a given week I tend to place loads of new and upcoming children’s books on hold at my library. As a result, I’m not precisely sure how Timeline From Black History showed up on my radar. Could have been from a review. Could have been sitting on a shelf in my library’s children’s room. Could have been from an ad somewhere. The point is that under normal circumstances I probably would have discounted it for a rather unfair reason: It’s a DK Book. You know what I’m talking about. I was a children’s librarian during the great thrall of the Eyewitness books that held children under their sway for a time. And while I’m sure there are still plenty of Eyewitness books out there, they just don’t have as strong a command over our young readers as they once did. Maybe that’s the internet’s fault. Maybe it was their own fault too. I mean, sometimes the facts were too brief, too normal, or too chintzy. That was my worry with this Timeline so I had a fairly simple wish for it: That it cover information that other Black histories did not. That it look above and beyond the usual slavery/Civil Rights Movement focus. Turns out, I was thinking too small. This book, which combines and updates some sections from the previously published Timelines of Everything and Timelines of Everyone is a marvelous panoply of moments long before slavery and far beyond the Civil Rights movement. You’ll find quite a lot of African history, both ancient and contemporary, as well as highlights of individuals, some you know, some you don’t. This book is NOT the only book on the subject that will ever be written, but right now it appears to be the only book so far. And I’m just relieved that it was good to begin with.

“Black History” is too broad a topic to encapsulate in 96 pages, so what do you do if you want to give an overview? Well, begin at the very beginning. The “Human origins” section shows how the entire human story begins in Africa. This is followed by a look at “Early African kingdoms”, notable personages extending between 1280 and 1663, and a dive into “Later African kingdoms” as well. When the slave trade is introduced it’s discussed within the context of the United States. Notable individuals receive two-page spreads, which not only tell their stories but will mention other related people in sidebars. For example, when discussing Harriet Tubman a sidebar highlights “Female activists of the 19th century”, particularly Sojourner Truth and Maria W. Stewart. Large moments in history like The Civil War and The Civil Rights Movement are mentioned, but do not get an inordinate amount of attention. There are consistent mentions of Africa throughout the book, and a shift to writers and artists throughout time. By the end you have two children highlighted (Mari Copeny of Flint and Marley Dias) and a host of “Black history stars” and groups that presumably didn’t quite fit in the rest of the book, including everyone from gay rights activist and drag queen Marsha P. Johnson to The Black Panthers to Black Lives Matter to Simone Biles. A glossary and index round out the backmatter.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

For adults like myself, paging through the book, what a person comes away with the most is this overwhelming sense that our history lessons in school failed us miserably. It took a Drunk History episode for me to learn about Mansa Musa. It took Hark, A Vagrant comics to teach me about Mary Seacole. And now it has taken this book to teach me, conservatively, a hundred more new things. The nomenclature in the Glossary section isn’t half bad either. Here you’ll find a definition for “enslaved person” but not a “slave”, which I appreciated. I wouldn’t call the book perfect by any means, though. The Harlem Renaissance, for example, gets shockingly short shrift, though it is mentioned in passing in the Zora Neale Huston section. The Caribbean, I would argue, deserved more time than the Toussaint L’Ouverture section and tiny mention of Aime Cesaire, and could have stood a contemporary examination. But there are so many mentions in this book of people and historical moments that seem vaguely familiar but which I never gave adequate attention. If this book has the potential to rectify this problem for new readers, even just a little, the implications could be huge.

I imagine the editorial conversations of what to include and whom to include must have been both intense and fascinating. A fly on a wall would have special insight into some of their decisions, I’m sure. Things like, why was Serena Williams included in a two-page feature while Venus was relegated to just a tiny encapsulation of her life? Who gets to be included as those tiny mentions on the larger two-page spreads? For example, inventor Lewis Howard Latimer (who, amongst many things, invented the carbon filament in light bulbs that lets them last longer) gets a sidebar of “Ignored inventors”. These include Sarah Boone (ironing board), Garrett Morgan (who got a picture book bio in 2019 called The Unstoppable Garrett Morgan by Joan Dicicco), and Marie Van Brittain Brown (home security). Surely there were other people to consider. Why these three? The decision making is almost half the fun of the book itself. I think that you could actually have a really interesting discussion with older kids where you show them the selections then ask them to make their own in the same style. What other inventors would YOU have mentioned? How would you redesign the page to show more? Could be a heck of an assignment.

But let’s address the elephant in the room here. The reason that I wanted to read this book the most was that I saw right away that it had a focus on the history of the African continent that I knew I wouldn’t be able to find in a children’s book anywhere else. “Early African Kingdoms” kicks us off and right away you see information that is all too brief. That’s sort of the point of it, though. It whets your appetite to see the pyramids of the Kingdom of Kush or to see the Aksumite Empire obelisks. Soon you’re taking a two-page deep dive into the life of Askia the Great, another on Mansa Musa, another on Nzinga Mbandi. And just to drill home that this book is not playing around, you immediately go from that into a section on “Later African kingdoms.” And yes, slavery enters into the story after that, but consider how many histories just begin with that part. Here, the book makes it very clear that Africa is a continent that deserves to be remembered as more than just a footnote. In fact, my favorite part of the book was the part I felt the most ashamed to see. Here I am, a 43-year-old woman, incapable of telling you what nations were colonizing Africa, where they were colonizing, and (fascinatingly) where they weren’t. I did not know that “Only Liberia and Ethiopia held onto their independence,” during the late 19th century land grab. Liberia I could have guessed at, but Ethiopia? To answer that question, we learn about Taytu Betul, the empress that successfully fought off the Italians to keep Ethiopia free. And just to be clear, after this, the book keeps including two-page spreads on people like Ellen Johnson Sirleaf (the first woman to become a head of state in Africa), Fela (Nigerian musician and political activist), Wangari Maathai (Kenyan environmentalist), and Kwame Nkrumah (revolutionary and politician). And don’t forget the two pages on Postcolonial Africa with a timeline that goes from 1957 to 2017. Is it insufficient? Of course. But it’s a starting point, where kids can take the Rwandan Genocide or the civil war in Sudan or the Angolan Civil War, get a brief sense of what they mean, and go from there.

Originally this book would have been published in Britain, yet for most of the book you don’t really get much of a sense of that. American dominates this discussion. I do wonder if the Brits, with an understanding of their own role in colonialism, weren’t better suited than us to lay out precisely what happened in Africa, particularly between the years of 1870-1900. But for the most part this book felt very American-made… right up until you get to Stormzy. And do not get me wrong. I absolutely love the Stormzy section. Stormzy, fellow Yankees, specializes in grime (def: “An type of electronic music that originated in Longdon, England”), is “one of England’s most successful musicians of the 21st century,” and started the literary venture #Merky Books. His sidebar focusing on “Black British music” turns out to be one of the most informative sections. Even so, tell me that it would have been there if this book hadn’t originally come out of London.

It’s an odd sensation to read a title that feels simultaneously like it’s packed full to brimming with so much pertinent information and, at the same time, be left with the understanding that it is completely insufficient in terms of additional details. It’s covering such a wide swath of history, but due to the nature of the piece it can’t dig down. All that can be done is to use Timelines From Black History as a starting point. You take this book and you use it to explore every person, place, and thing that it mentions on your own. It’s not going to help you there, of course. Like all DK Books there is no Bibliography or recommended list of Sources. And it should be quite clear that this book is where this conversation begins and NOT where it ends. Better books than this one, more complete books, absolutely 100% have to start getting written and published. But if I had to begin somewhere, this is a decent place to begin. If nothing else, it truly conveys how ridiculous it is to try to encapsulate the entirety of the Black experience in a single book. Now take this, give it to a kid, blow their minds, and then run to a library to supplement, supplement, supplement. A beautifully designed starting point. Now can I have a Mansa Musa picture book biography, please?

On shelves now.

Source: Copy borrowed from library for review.

Filed under: Best Books, Best Books of 2021, Reviews, Reviews 2021

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

The Moral Dilemma of THE MONSTER AT THE END OF THIS BOOK

K is in Trouble | Review

Fighting Public School Book Bans with the Civil Rights Act

ADVERTISEMENT

Wow, sounds fascinating! I’ve been deep diving into West African history and yes it’s incredible!! Liberia probably remained independent because it was established and protected by America, it was actually America’s attempt at colonization. There’s a Canadian scholar who’s delved into historical documents and proven that long before Columbus arrived in America, Mansa Musa’s uncle did. He presented his thesis to a body of McGill scholars who were planning on excoriating him, but at the end of his presentation they admitted the evidence was overwhelming, hiding in plain sight.

Just speaks to the incredible erasure of African accomplishments.

I knew about Liberia but NOT about Mansa Musa’s uncle! I hope that man wrote a book of some sort. Or, if not, that someone else will.

Thanks for calling attention to this DK book; I still like them!

It’s out of print, but Leo and Diane Dillon did a gorgeous picture book biography: Mansa Musa: The Lion of Mali (2001).

*only a cloud of dust remains where once I stood*

Getting that book NOW!

He did! It’s called Deeper Roots. The evidence is compelling. It’s a summation of all the research he’s done. I used it for my research into West Africa for an adult historical novel I’m writing.

I can’t get into all the Mansa Musa stuff but I do touch on it.