Review of the Day: The Crayon Man by Natascha Biebow and Steven Salerno

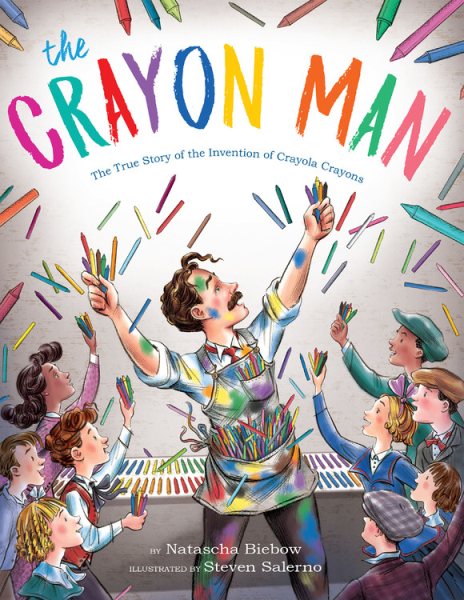

- The Crayon Man: The True Story of the Invention of Crayola Crayons

- By Natascha Biebow

- Illustrated by Steven Salerno

- Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

- $17.99

- ISBN: 9781328866844

- Ages 4-7

- On shelves now

Someone once pointed out to me that a good 30% of my reviews start out with me saying, in one form or another, something along the lines of “I didn’t think I’d like this book but then I read it blah blah blah amazing blah blah blah original blah blah blah go read it.” And the jury finds me . . . guilty as charged. See, writing original reviews can be tricky so it’s easy for a reviewer to fall into some old established (read: brainless) methods of putting words to a page. I mean, it’s not like it’s untrue when I write that stuff. I really didn’t think I’d like the book in question, but even so, do you know what I never care to examine in those reviews? Whether or not my inexperience with the subject matter has given a rosy-colored tint to the book itself. Would I be as gaga about it if I hadn’t walked in with lowered expectations? It’s not the kind of thing that’s easy to ascertain. Naturally, all of this brings us to The Crayon Man by Natascha Biebow and Steven Salerno. Here we have yet another book that I viewed initially with distain. I mean, a picture book biography of the man who invented Crayola? Doesn’t that just make this book essentially a 40-page advertisement for a product? As per usual I read it, loved it, and started proselytizing it to anyone in my immediate vicinity. Lowered expectations aside, though, is it actually any good? Let’s take into account the writing, the subject matter, the art, and the accuracy. A nonfiction picture book biography is only as good as the sum of its parts. And these parts? Good to the last drop.

Running a company that specializes in the color black would seem to be an unlikely beginning for the future creator of Crayola crayons, but that’s how Edwin Binney started out. His company sold the carbon black pigment that got used in everything from shoe polish to rubber car tires. An inventor at heart, Binney listened when his wife, a former schoolteacher, told him that the world needed better, cheaper crayons. After much trial and error, experimentation and failure, and moments of inspiration, Binney had it down. Not by himself. Not alone. But with the help of others along the way who, together, made the world a little more colorful.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Right from the start I liked what Biebow was laying down here. She knows how to use repetition to keep the reader interested. She places little text boxes of facts in the margins for those readers that would like to learn more. This is perfect for readers of different age levels (and interests too!). Then, in the text itself, not even the art, Biebow lists Binney’s prior accomplishments. The gray slate pencil, the white chalk, and the black crayon (that wasn’t really for kids). She doesn’t shy away from the chemistry that went into making this new iteration of crayons. I also couldn’t help but love that Biebow drills home the idea that Binney’s genius came not from his own cranium, but because he listened to other people’s advice. This is particularly true of his wife. The book makes a point to repeat that Binney listened to her, whether she was telling him that kids needed better crayons in the first place or when she personally came up with the name Crayola from the French word for stick (“craie”) and “ola” from the work “oleaginous”.

Okay, but let’s get back to a concern I had walking into this book. Is it, in fact, a walking advertisement for Crayola? Putting aside the fact that Crayola’s pretty much the only name brand crayon a person can think of off the top of their heads, there’s no denying that the book paints Binney in a pretty sunny light. Yet there’s also no getting around the fact that here we have a man dedicated to making something fun for kids. There’s a lot to be said for writing a biography about a product that children have not only heard of but also taken for granted. Crayons are so ubiquitous to the childhood of a number of American children that this might actually be a book they take an interest in. Finally, consider the cover. Think about how easy it could have been to take the word “Crayola” and make it bigger, bolder, and more prominent. Instead, it’s squirreled away in the subtitle without so much as a different colored font. The focus here is on the man, not the company, for the most part.

So impressed was I by Biebow’s skills at the nonfiction picture book bio form that I skipped on ahead to her biographical bookflap to see what else she’d done. You can imagine my surprise when I found that this book is, in fact, her nonfiction debut. Apparently she just knows how to knock ‘em out of the park on a first go-round. Honestly, when I’m reading other biographies and hitting things like fake dialogue, false histories, made up characters, etc. I kind of want to grab this book and hand it to those other authors saying, “Look! Look! You don’t have to rely on any of that garbage. You can make a book fun, and interesting, and accurate without all of that! See?” Because it isn’t just the writing of the book itself that wins a person over. It’s the backmatter. For a woman who grew up watching the episode of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood where they see how crayons get made, the full-color photographic section “How Crayola Crayons Are Made Today” just hit all my buttons. Then you get a full page of additional info on Binney himself. And then finally you get the motherload. A Selected Bibliography that separates itself out into Primary Sources (subdivided into “Print” and “Interviews & Correspondence”) and Secondary Sources (subdivided into “Books & Articles”, “Websites”, and “Videos”). And yes, that old Mister Rogers video? It’s there in the Bibliography. Wonder of wonder, miracles of miracles.

Selecting Steven Salerno to do the art in this book was an inspired choice. Salerno’s not unfamiliar with picture book biographies, having worked on titles like Brothers at Bat and Pride. His is a difficult artistic style to describe. It is, above all, distinctive. Would you like to know the difference between a good picture book biography and a really good picture book biography? The difference is in the details. Take the opening of this book. Biebow writes about a man who loved color, but ran a company that worked almost exclusively in the medium of black. Seeing an opportunity, Salerno takes this opening and works hard to make that contrast palpable. Standing amidst reds, blues, yellows, purples, blues, and greens is an Edwin Binney with a happy upturned mustache. Turn the page and the colors are muted considerably, overwhelmed by the soot and dark colors of the factory. Binney stands in the same position, but his mustache has drooped considerably. That mustache, by the way, should get a supporting role nomination alongside his eyebrows. The two facial hairpieces work in tandem to clarify the man’s moods, confusion, and thought process.

If I could change anything about the art, I might try to give it a greater range of ethnicities. It is entirely possibly that Binney employed an all-white workforce. That said, just because you’ve placed your book in the past, that doesn’t mean you can’t work in a diverse array of people in other places. For example, for the section on the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis, I couldn’t help but notice that the throngs of people were all white. Not the case in real life and unnecessary here, I’m afraid. There are other little moments that like that could have given the book a depth it lacks in this area. A missed opportunity to give this book a little actual color.

Some wag will probably say (if they haven’t already) that it seems strange that a picture book biography of Edwin Binney isn’t illustrated in the medium of crayons. An interesting point, I’m sure. Would a crayon-illustrated version of Binney’s life be better for its reliance on his preferred form? Or would it just be a kind of unnecessary gimmick? Only one way to find out. Clearly there need to be more books on Binney out there. But since the likelihood of any of them being quite as good as this one is slim, I’m happy to stick with Biebow and Salerno’s creation in the meantime. It’s just the ideal use of great writing without cheating. It’s filled with facts and backmatter, but also makes the subject interesting to kids. It’s beautiful to look at and while I would have made some changes, it stands as a pretty darn good look at a man, a plan, a crayon. Crayola.

On shelves now.

Source: Galley sent from publisher for review.

Filed under: Best Books, Best Books of 2019, Reviews, Reviews 2019

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Name That LEGO Book Cover! (#53)

K is in Trouble | Review

Fighting Public School Book Bans with the Civil Rights Act

ADVERTISEMENT

You’ve sold me on this book. I also like the category of “books I didn’t think I would like, but did.” That would make a nice anthology. A related book, from 2009, is The Day-Glo Brothers: The True Story of Bob and Joe Switzer’s Bright Ideas and Brand-New Colors, by Chris Barton and Tony Persiani. It won a Siebert Honor. There is day-glo lettering on the cover, and the book is wonderful.

I also like a picture book about the possibly controversial Barbie, and her creator, Ruth Handler. The Story of Barbie and the Woman Who Created Her, by Cindy Eagan and Amy June Bates, might also fall into the category which you apply, at least for some readers who are not so judgmental about the 11 inch doll.