Guest Post: Mildred L. Batchelder and the International Youth Library: Part I – Who Was Batchelder? by David Jacobson

On September 14, the International Youth Library (IYL) in Munich, Germany, will mark its 75th birthday. When it opened its doors, it occupied a few rooms of a war-damaged villa and amounted to just several thousand books. Today it’s the world biggest children’s book library, by far.

The Youth Library was the creation of the German Jewish émigré Jella Lepman who, remarkably, decided to return to Germany immediately after World War II. Her goal was to eradicate the ultra-nationalism and ethnocentrism that led to the war by teaching children to be more understanding of their peers in other countries. She aimed to do that by sharing children’s books across borders and thereby instilling empathy at a young age.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

America played a major part in the creation of the Library, too. In the following two blog posts, which we will post over the next two days, David Jacobson will introduce the work of Mildred L. Batchelder, a long-time ALA administrator and Evanston, IL resident (yay!), and share how she helped make the IYL a reality, from 4,500 miles away.

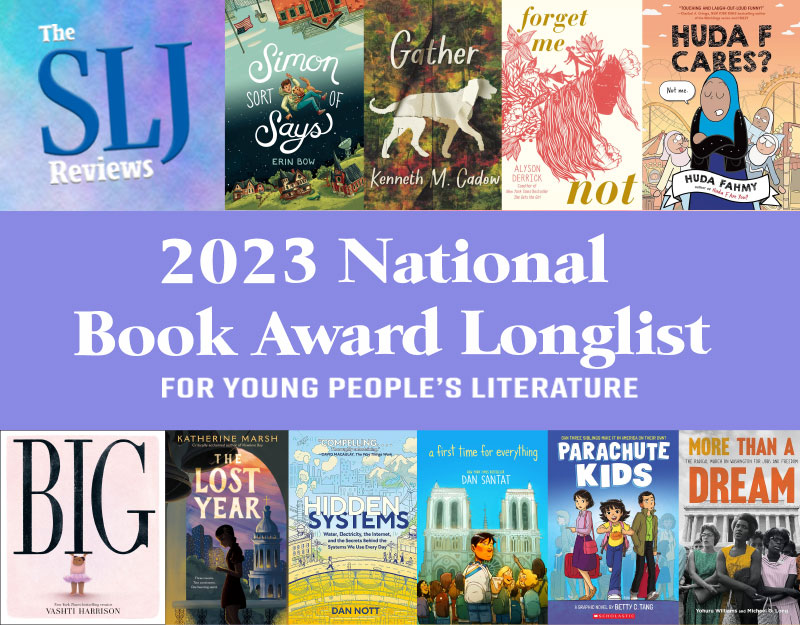

Few of you probably know much about Mildred L. Batchelder. If at all, you might have heard of the ALA’s Mildred L. Batchelder Award, which was, of course, created in her honor. The prize, sadly one of the lesser-known awards of those bestowed by the ALA every January, honors children’s books translated from other languages and published outside the United States.

The prize recognizes Batchelder’s deep interest in and contribution to internationalizing children’s literature and children’s libraries. Her contribution was indeed significant, as I will explain, but the award hardly recognizes Batchelder’s many other contributions to librarianship. According to Dorothy J. Anderson, whose 1981 dissertation on Batchelder remains the only comprehensive biography of her life (and who, for three years in the early 1960s, acted as her assistant), Batchelder played “an early and significant part in the promotion of school library service, federal funds for libraries, audio-visual materials, interagency cooperation, intellectual freedom, child advocacy, and [italics, mine] international relations.”i

Batchelder joined the ALA in 1936 as its first school library specialist, after eight years as a practicing school librarian. For the first 15 of her 30 years at ALA, she “basically served as ALA’s specialist and division chief in the fields of school, children’s, and young people’s library service.”ii This small and physically unassuming woman grew to become a powerhouse in the library world, much like prominent New York City librarian Anne Caroll Moore had been a generation before her. Unlike Moore, however, who had the reputation of being able to destroy the fortunes of a single children’s title by penning a negative review, Batchelder took a somewhat less imperious approach. Though she had an “acerbic tongue” and her confrontations with provincial thinking were “legendary,” according to Anderson, she “often chose to reach her goals through the training and encouragement of others” and was also “known for her charm and international diplomacy.”iii Still, “Batch”, as she was sometimes called by those who knew her, was perceived to be so powerful as head of the ALA’s Division of Libraries for Children and Young People, that in the late 1940s, school librarians staged an open revolt, seeking their own division in the ALA separate from that of the public librarians. They succeeded and for a time, Batchelder lost her job as executive secretary of the division.

Nevertheless, Batchelder continued to soldier on for another 15 years at the ALA. A legendary story has come down to us, again through Dorothy Anderson, suggesting her fixity of purpose:

“Apparently Mae Graham, Nettie Taylor, Margaret Nicholsen [Batchelder’s life partner] and Mildred Batchelder were motoring through Maine one summer. They all like to swim and watch birds. Driving along through the Maine woods one warm afternoon, they came upon an absolutely beautiful pond, but alas, they had no swimming suits with them. It was decided that Margaret would watch for cars while the others went skinny-dipping! They were enjoying the water when suddenly Margaret heard a car approaching. “DUCK! DUCK!” she yelled. Mae and Nettie plunged under the water. Mildred, however, rose up from the water and said, ‘Where? Where?’”iv

It was in Batchelder’s early, and rare, commitment to international children’s literature where she made her greatest mark. In 1937, barely a year after she joined the ALA, long-running Executive Secretary Carl Milam asked her to prepare a list of Latin American children’s books. Batchelder canvassed libraries in the region, but found few books in English which “authoritatively and sympathetically” portrayed Latin American countries. She therefore recommended that the ALA conduct a complete study of all such books. Librarians, she wrote Milam, “believe that the best children’s books of all countries should be made available in appropriate languages to the children of all countries.”v

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Only a few years before, President Franklin D. Roosevelt had announced the Good Neighbor Policy. Though its primary purpose was to end US interventionism in Latin America, it also sought to improve cultural relations between America and its neighbors. This took on greater significance and urgency as the US observed growing Axis influence in the region. In 1938 the State Department set up a Division of Cultural Relations, whose mandate was to develop a coordinated international cultural relations policy which included the use of books and libraries to strengthen relations between America and other nations. The ALA, in conjunction with the federal government and private philanthropies, most notably the Rockefeller Foundation, helped spearhead these efforts.

“For a brief span of years,” explains Gary Karske, author of Missionaries of the Book, The American Library Profession and the Origin of United States Cultural Diplomacy, “the American Library Association occupied a unique position as a voluntary organization, able to bring to bear on a worldwide basis its expertise and its ideals. It was a singular period in the organized library profession’s century-long history, a period during which its influence in government and foundation circles and abroad, reached an apogee in ways not again attained and when American librarianship achieved a new respectability and recognition as a profession with cultural and intellectual significance to the world.”vi

It was in this context that Batchelder was able to contribute to the internationalization of the world of children’s books. During World War II, the ALA section for library work with children recommended books for translation, created an exhibit of Latin American children’s books which could be sent to North American libraries, and worked with the Children’s Library Association to send books in 12 languages to children in war-torn countries. In 1943, Batchelder even suggested establishing an international children’s book collection in Chicago. She believed the collection would be “useful to students of education and library science, valuable in the training of people for postwar international relations, interesting for students of propaganda to see ways in which children are being indoctrinated with ideas considered important by national leaders, and finally, the collection would aid publishers in their decision of what books to translate for English speaking children.”vii

It was therefore no surprise that Batchelder responded enthusiastically when Jella Lepman sought her help with plans to build an international youth library in postwar Germany.

David Jacobson is a writer, journalist and Japanese translator. In 2016, he published Are You an Echo? The Lost Poetry of Misuzu Kaneko, a picture book about and by a beloved Japanese children’s poet. He is in the process of writing a biography of Jella Lepman and this September will be participating in a conference on her life to be held at the International Youth Library in Munich.

i Dorothy J. Anderson. “Mildred Batchelder, a Study in Leadership,” PhD diss., (Texas Woman’s University, 1981) iv.

ii Anderson, 59.

iii Anderson, X.

iv Anderson, 330.

v Anderson, 52.

vi Gary E. Kraske, Missionaries of the Book, The American Library Profession and the Origin of United States Cultural Diplomacy. (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1985) 3.

vii Anderson, 100.

Filed under: Guest Posts

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Magda, Intergalactic Chef: The Big Tournament | Exclusive Preview

Fifteen early Mock Newbery 2026 Contenders

When Book Bans are a Form of Discrimination, What is the Path to Justice?

ADVERTISEMENT

The photograph of this site is so beautiful. My husband was stationed in Heidelberg, Germany during the Vietnam War. We lived there for eighteen months. Munich was not far away but I had no idea this library existed.

What an incredibly interesting post today. All the information was new to me. I’m looking forward to reading the next two.