“The very unlikely Forrest Gump of the avant-garde.” A Nicholas Day Q&A about Nothing: John Cage and 4’33”

I like a book that explains to me in the simplest possible terms concepts that have eluded me my entire life. This is probably why I have a tendency to prefer to deal with children’s books, and it further explains my particular fondness for nonfiction. Take, for example, the composer John Cage. Not being particularly proficient in the avant-garde, I think it would be fair to say that until very recently I have been dismissive (at best) of his famous work 4’33”. You’ve probably heard of it. It was the composition that consisted of a pianist sitting down at a piano, playing nothing for four minutes and thirty-three seconds. For my part, it always struck me as the equivalent of painting a giant white canvas entirely in white paint. What’s the point? And then, I had to go and read Nicholas Day’s latest book.

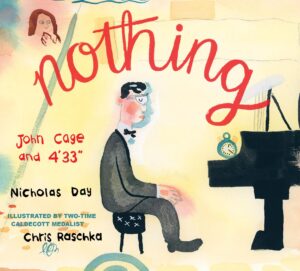

Nicholas Day, as you may recall, won the Sibert Award for children’s nonfiction just this past January for his incredible The Mona Lisa Vanishes. That book clocked in at a whopping 276 pages. This next title? It’s a picture book. Slim and sleek, with art from none other than two-time Caldecott Award winner Chris Rashka a.k.a. the guy who loves doing musician-based picture book bios so much that he once did one on Sun Ra. No kidding.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

The description of this book, called Nothing: John Cage and 4’33”, is fairly simple, but I’ll let Neal Porter Books take it from here:

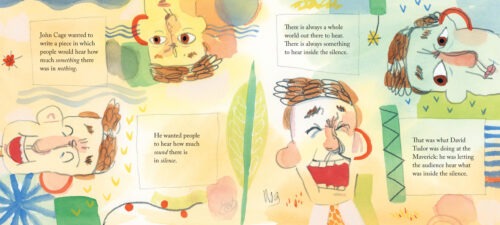

One night in 1952, master pianist David Tudor took the stage in a barnlike concert hall called the Maverick. A packed audience waited with bated breath for him to start playing. Little did they know that the performance had already begun.

A rain patters.

A tree rustles.

An audience stirs.David was performing John Cage’s 4’33”, whose purpose is to amplify the ambient sounds of whatever venue it inhabits. That shocking first performance earned 4’33” plenty of haters; and yet the piece endures, “performed” by the smallest garage bands and the grandest symphonies alike, year after year. Its fans hear what John Cage hoped we would hear: “Nothing” is never silent, and you don’t need a creative genius, a concert hall, or even a piano to hear something worthwhile. All you have to do is stop and listen.

Nicholas Day’s text is reverent with a healthy drop of humor, warm and refined; two-time Caldecott Medalist Chris Raschka’s childlike pencil-on-watercolor artwork is uninhibited and electrifying, with all the visionary spirit of the work it chronicles. Guaranteed to spark generative thought and lively debate among readers of all ages, Nothing is not to be missed.

The chance to talk to Nick? Nothing could stop me:

Betsy Bird: Nick! What a delight to lob questions in your general direction. And congrats on that shiny Sibert Award you nabbed for THE MONA LISA VANISHES. Well deserved! Not content to rest upon your laurels, I see that you’ve switched gears slightly and decided to conquer the world of nonfiction picture books as well. And rather than do something easy, like the metamorphosis of butterflies or some such stuff, you’ve opted to explain to kids what precisely was going on with John Cage’s “4’33”. Where on earth did this project come from?

Nicholas Day: Betsy! It’s wonderful to be back here and thank you for your very kind words about The Mona Lisa Vanishes.

I wrote the manuscript for Nothing many years ago now—well before I was publishing for children. I actually remember where I wrote it: in Remedy House, a (perfect) cafe in Buffalo, New York. (I think I even remember the table.) I’d written a few picture book manuscripts before, but I’d never published anything and I’d never written a nonfiction manuscript. I suppose that John Cage’s 4’33” is a somewhat unusual topic for your first nonfiction foray, but it all felt very natural at the time.

That’s partly because I’m a fool, of course, but also because 4’33” –a composition of nothing at all—is an idea that seems perfectly suited to young readers. It’s weird. It’s funny. The whole thing feels like something you’re obviously not supposed to do—and of course that’s appealing. The whole thing made very serious people very mad—and of course that’s appealing. And once you get past the idea of the nothingness of it all—of a blank where the something should be—Cage’s core idea makes perfect sense. I’d wager that it makes more sense to younger minds: they’re more willing to hear what’s always out there, all the sounds—the world—that we skip over every day.

BB: Can’t argue with you there. You know, often I find that when I, as the adult gatekeeper, am confronted with information in a work of children’s nonfiction that I did not already know/appreciate, I cannot help but reflect on how lucky kids are today to have access to such books. How much of Cage’s story behind this music did you already know when you dove into the research process and how much did you yourself learn?

Nick: Yes, there’s so much out there now—these children today have no idea how impoverished the nonfiction stacks of our youth were. We pretty much just had George Washington, Betsy Ross, and one extremely beaten-up book about shark attacks.

I’ve known about 4’33” for years, but only in the broadest strokes. I knew almost nothing about the premiere at the Maverick Hall in Woodstock, which became the backbone of the book. The composition received… a mixed reception, let’s put it that way. Once I realized I could tell the story through that premiere—the reader discovering what’s going on in much the same way that the audience discovered it—the whole manuscript snapped into place. Reading about Cage is always a treat because his life touched of the last century—not just music, but dance and art, too. He’s everywhere, the very unlikely Forrest Gump of the avant-garde.

BB: The book is a marvelous complement to last year’s fellow John Cage-related title Beautiful Noise by Lisa Rogers and Il Sung Na. But while that book sort of encompassed Cage’s entire life, yours zeroes in specifically on this piece as its focus. Was there ever any inclination to show more of his life in the book, or did you keep your focus centered tightly on the piece alone?

Nick: I was always focused on the piece. There’s a whole world in 4’33”—in many ways that’s the point of it—and so I wanted to highlight that. The reader needs to know enough about Cage to contextualize the piece, and that’s in the book, but I wanted the story to be centered on 4’33”.

I like that sort of limitation, though; I don’t mind losing the biography. It’s a little strange to write a nonfiction picture book and say you’re not interested in information, and I’m exaggerating for effect here, but that’s sort of how I feel. The facts are less important than the resonance. All that information—it has a short half-life. The feeling of the story is what sticks around. You can cut everything except the feeling.

BB: When we think of music in children’s nonfiction, we think of Chris Raschka. Pairing him with your writing feels like an “Oh, of course” moment. It simply seems made to be. Were you familiar with Chris’s other jazz and music-related books prior to this? And what do you think of the final project?

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Nick: I was very familiar with Chris’s work—as is anyone who cares about picture books. So when Brenda Bowen, who represents both of us, suggested sending him the manuscript, it seemed both logical (because of his music books) and incredible (because, you know, he’s Chris Raschka). I was delighted when he said yes, and then astonished when I saw what he’d done with it.

BB: And now the question I’ve been wanting to ask from the start: What’s next for you? What’s coming up? What’s on your plate?

Nick: The next major thing is a narrative nonfiction book about the so-called Year without Summer—how a couple of hundred years ago, there was a massive volcanic eruption, and that eruption sparked a climate shock. All over the world, people discovered that things they’d taken for granted—rain and sun in the right amounts at the right times, for example—were no longer to be taken for granted.

Then the skies shifted again and all that the chaos and fear were forgotten. The fact that we live by the grace of a habitable planet, a habitable climate—that was forgotten, too.

But it was, you know, a warning.

There’s tragedy here, but there’s also hope—and there’s Frankenstein.

That’ll be out in 2025 from Random House Studio and Annie Kelley.

As far as I’m concerned, it’s not a good interview unless it literally ends with tragedy, hope and Frankenstein.

Thank you, Nick, for taking the time to talk with us about your book! Many thanks too to Anna Abell and the folks at Holiday House for giving me this chance to chat with him. Nothing: John Cage and 4’33” is available for purchase right now, so I absolutely insist that you raid you nearest library/bookstore for a copy. There’s nothing to it (okay, okay, I’ll stop now).

Filed under: Best Books, Best Books of 2024, Interviews

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Tegan and Sara: Crush | Review

The Seven Bills That Will Safeguard the Future of School Librarianship

Take Five: Dogs in Middle Grade Novels

Gayle Forman Visits The Yarn!

ADVERTISEMENT

Thank you for bringing this book to my attention. John Cage’s revolutionary role in modernism can’t be understated, nor can the value of quiet, nor can the importance of communal performing arts experiences. I can’t wait to check it out.

I am grateful for my experience listening to live performances of classical piano when only the one instrument and performer were involved. I have experienced the pause between notes and that precious few moments of silence between movements and also at the conclusion of a piece. Those moments of silence are as profound and meaningful for me as the actual musical sounds. I look forward to exploring NOTHING.