31 Days, 31 Lists: 2023 Translated Picture Books

What can a translated picture book win in America? Well, if memory serves then the Batchelder Award can technically go to picture books. So that’s one! That said, the rules changed slightly recently and the only books available to the nominating committee are the ones where the translator’s name appears on the cover. That’s great for me! After all, part of my job on this site consists of tracking down these translators, wherever their names may hide in their books.

Today, you’re going to witness some of the most interesting, original, and downright beautiful books of the year. They run the gamut from hilarious to tear-jerking.

You can find the full PDF of today’s titles here.

Interested in other lists of translated children’s books? Then check out these lists from previous years:

2023 Translated Picture Books

Afterward, Everything Was Different by Rafael Yocktend, ill. Jairo Buitrago, translated by Elisa Amado

[Translation – Spanish]

A group of early humans struggles to survive during the Pleistocene era. Meanwhile, a single girl watches and records everything that happens to them for posterity. An epic wordless tale about our earliest ancestors. I hereby declare 2023 The Year of the Wordless Picture Book. Between this and Aaron Becker’s The Tree and the River, we’re seeing massive time periods covered without a word on the page. Amazingly, this book highlights that impossible moment where humanity went from just trying to exist to trying to tell our stories to one another. It’s black and white, but you quickly forget about all that as you follow this group of humans (and their a human-adjacent friend, which I kind of love) tromping about during the Pleistocene era. I love the cinematic opening and it’s interesting watching their numbers deplete over time. I could read this again and again and notice something new with each read. Wholly, utterly engaging and original.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

The Amazing and True Story of Tooth Mouse Pérez by Ana Cristina Herreros, ill. Violeta Lópiz, translated by Sara Lissa Paulson

[Translation – Spanish]

Losing teeth is “the gift of growing up”. See how the Spanish Tooth Mouse tradition has changed over the years and how it connects to our very own Tooth Fairy. Oh, I just love this! I’ve heard of teeth mice before and I’ve even seen books about different losing-your-teeth traditions from around the world (anyone remember I LOST MY TOOTH IN AFRICA by Penda Diakite?). Still I’ve never seen a really really really good book on the subject before. Now, at long last, I think I have. This covers traditional tooth mouse folktales, sure, but it also acknowledges how times change and how people, and traditions, have to adapt. If you don’t live in houses with roofs then throw your tooth in the fireplace. There aren’t fireplaces now? Then put the teeth under your pillow! And then to weave in other tooth fairy/insect ideas as well? Fantastico. A thorough winner from start to finish.

The Bear and the Wildcat by Kazumi Yumoto, ill. Komako Sakai, translated by Cathy Hirano

[Translation – Japanese] +(BB

A little bird has died and Bear, the bird’s best friend, misses him dearly. When a new friend urges him to remember the bird, the story becomes a beautiful one of hope and healing, deftly told. Great writing (“His downy feathers were the colour of coral and his tiny black beak gleamed like onyx”) and the black images appear on the page as if they were scrubbed away from the surrounding brownish gray, like relief paintings released. It’s quiet and contemplative and rather lovely. I personally consider it this year’s Circles in the Sky.

Bear Is Never Alone by Marc Veerkamp, ill. Jeska Verstegen, translated by Laura Watkinson

[Translation – Dutch]

These days if I see a bear playing a piano in the woods then the first thing I think of is The Bear and the Piano by David Litchfield. This book certainly has some surface similarities, but at its core it’s just an interesting take on being alone and being alone together with someone you like. Bear’s pretty much the most amazing pianist you’ve ever heard. But when his woodland fans insist that he keep on playing, he has difficulty ditching them without causing offense. Only the zebra expresses gratitude for Bear’s playing and offers to read to him in return. The story is nice, but it’s Verstegen’s striking black and white mix media illustrations, with just a hint of red, that suck you into the story. I love these front endpapers, with their almost foggy view of the animals attentively listening amongst the trees. An immersive, slightly strange, rather touching tale.

Because I Already Loved You by Andrée-Anne Cyr, ill. Bérengère Delaporte, translated by Karen Li

[Translation – French]

There is no one right way to write a book about a baby sibling dying at birth. And considering how sad and common this is, this is the first book of its kind that I can recall seeing. Topics of this sort too often are published by people with the requisite “M.D.” or “PhD” after their names on the cover. I don’t know that I particularly like such books, most of the time. Now Ms. Cyr is an early childhood educator from Quebec with a background in special education. Somehow she perfectly captures some of the feelings a child may have when all that build up to a new baby sibling is met with the heartbreaking news that there will be no new baby at all. This book is unafraid to dip into the deep well of sadness that the whole family feels after such an event. It also offers the light of hope, and I truly feel that that hope is earned by the text. The gentle assurance that this is no one’s fault is key. In her Author’s Note, Cyr notes that “I have worked with children for many years, and for me, it is essential to be honest and explain the truth to them in accessible words. I wanted to make sure that young readers understand that it’s normal to be sad, while also leaving them with a feeling of hope and love at the end of the story.” I can think of no better book on this subject than this. Previously Seen On: The Message Book List

The Biggest Mistake by Camilla Pintonato, translated by Debbie Bibo

[Translation – Italian]

Overconfidence is the name of the game in this lovely little title. Given the chance to catch a gazelle on his own, a little lion is fairly certain that he’s got this. To his complete bafflement, however, the gazelle gets away. Over. And over. And over. With all the high humor of a coyote and roadrunner cartoon, the two duke it out. The lion receives a variety of unhelpful advice from a bunch of other creatures and Pintonato gets a fair amount of humor out of the facial expression on the creatures in this book. Also, and to be perfectly frank, I think she nails that ending. It’s silly and it works. A title that eschews giving kids some moral lesson in favor of guffaws.

The Bridge by Eva Lindström, translated by Annie Prime

[Translation – Swedish]

For all that I say that we currently live in a Golden Age of Children’s Literature (and truly I believe this to be so) I can’t help but note that the bulk of the picture books I read any given week are awfully samey samey. Kids like samey samey fine since they often lack a system of comparison, but I would like to propose that we pepper our regular old standard picture book literature with the occasional bit of bizarreness. What kind? Introducing, The Bridge. A story that seemingly goes nowhere until it ends on a disconcerting note. Now this is a Swedish import and I will tell you right now that there are a fair number of parents out there that are not amused by any book that disconcerts them, particularly if it’s written for four-year-olds. Nevertheless, it would do your child’s brain a bit of good to indulge in this particular beauty, at least once. The storyline follows a little pig who is informed by a wolf that the bridge is closed up ahead. While it is repaired he is redirected to the wolf’s house, where he sups with two wolves. It’s laden with the sense of something threatening waiting in the wings, and yet nothing bad ever happens to the pig. Nonetheless, you may feel a bit of a shiver down your spine when you learn at the end, alongside the pig, that there was never any bridge in the first place. An excellent book for discussion, I’ll tell you that!

The Brothers Zzli by Alex Cousseau, ill. Anne-Lise Boutin, translated by Vineet Lal

[Translation – French]

Let’s say that you are a writer of picture books and you are handed an assignment to write one about inclusion, immigration, and acceptance. Make it good. Make it furry. Just fill the darn thing up with bears. Now go. Of the requirements I just listed the most difficult one, without a doubt, is the “Make it good” part. Lord knows we’ve seen plenty of books on immigration or “accepting others” but boy can they get preachy real fast. To do the job properly you need to be a little weird. And Alex Cousseau is unafraid to bring the weird. The whole concept of this book is bizarre, but as extended metaphors go, I’m really quite fond of it. It’s told entirely in the first person (which is kind of rare right there) by a little girl who lives in a simply marvelous little green house deep in the forest. One day three bears arrive introducing themselves as “the four brothers Zzli”. Why four? “Maybe because we eat enough for four.” In spite of their prodigious appetites she finds them “truly delightful.” Driven out of their home they’ve gone through a lot of hardship in their travels and just want to settle down somewhere safe. She invites them to stay with her and all is well for a time. Unfortunately it soon becomes clear that the other animals in the forest do not trust these bears a jot and when that fear turns into pretty much firebombing the girl’s cottage, the bears decide to leave. She goes with them (I mean who would want to live in that community?) with the hope that someday they’ll find a spot where they can all belong. There’s a wordless four-page spread at the end that suggests that they succeed. One can hope, that’s for sure. Done entirely in primary colors, it’s just the loveliest story, but doesn’t skimp on showing how fear makes people do terrible terrible things. Man. You gotta read this one. Previously Seen On the: Message Book List

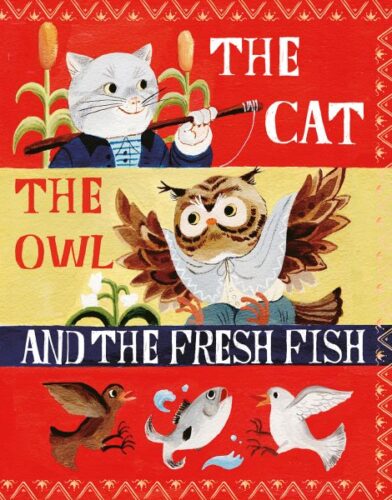

The Cat, the Owl, and the Fresh Fish by Nadine Robert, ill. Sang Miao, translated by Nick Frost and Catherine Ostiguy

[Translation – French]

I’m sort of old-fashioned when it comes to folk and fairy tales. Generally speaking I try to avoid including any original ones on these lists. I don’t mind fractured tales, of course. Or tales that add some more contemporary elements. But wholly new? Not usually my style. Yet here we are, with me taking a gander at this little French-Canadian import and just absolutely adoring it! The story has all the hallmarks of an Aesop fable. In it, you’ve an owl who is trapped by a log on his foot. A nearby cat refuses to help because it has spotted a basket of fish in an abandoned boat in the middle of the pond. The owl keeps surreptitiously giving the cat advice on how to get closer until it manages to accidentally/not accidentally get the cat to pick up the log on its foot. The art of Sang Miao, meanwhile, has all the hallmarks of a classic picture book from 70 years ago. I walked in uncertain (the cursive letters threw me off at first) and then was utterly charmed. A delight.

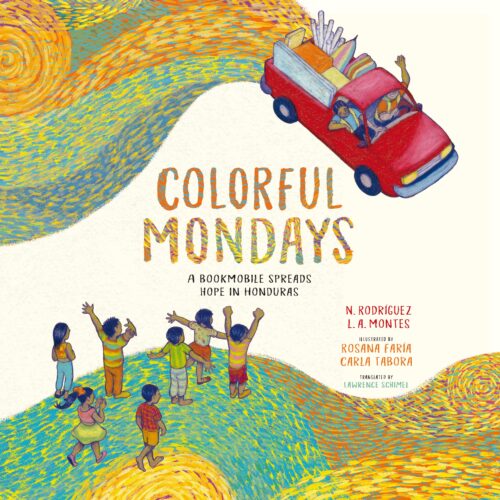

Colorful Mondays: A Bookmobile Spreads Hope in Honduras by Nelson Rodríguez and Leonardo Agustín Montes, ill. Rosana Faría and Carla Tabora, translated by Lawrence Schimel

[Translation – Spanish]

Right off the bat, love love love the art in this book. I’m not sure in what way Rosana Faría and Carla Tabora collaborated together, but whatever their magic is, let’s get some more of it! In this title they create the art with crayon and computers, and the results are stunning. Set in Honduras, the book is a paean to a particular bookmobile/mobile library project that travels around Villa Nueva, Nueva Suyapa, and Los Pinos. The book itself is written by the director of the JustWorld International Asociación Compartir mobile library project and a bookseller. It tells about a kid living in an economically depressed town who finds and gives so much joy thanks to the bookmobile. And I know you’ve seen a lot of bookmobile/burro/pack horse/camel related mobile library tales before but this one has a great deal of heart and is worth looking at closely. Trust me.

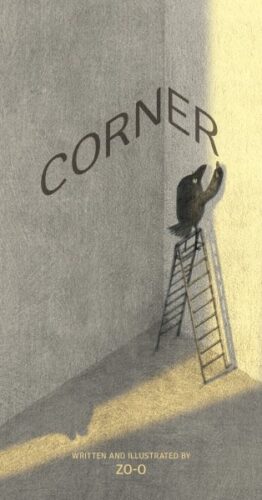

Corner by Zo-O, translated by Ellen Jang

[Translation – Korean]

This past March I had the opportunity to attend the Bologna Children’s Book Fair, and almost immediately I made a beeline for the Korean booth. If you want innovative international picture books that appeal to Americans, that’s the place to be. Owl Kids knows this. They’re Canadian and you can bet that they didn’t hesitate to snatch this book up when they saw it. It has a distinctly Suzy Lee feel to it, since, like her, it’s a book unafraid to use its gutter. Tall and thin, the gutter is a corner in a room. The view of it never changes and a crow slowly begins to install furniture and then to design the walls. As it does so, the entire feel of the place changes. The information on creator Zo-O says that the O in her name stands for “the Chinese character for crow, making her full name “Crow Zoo” in English.” Which, as names go, has gotta be my favorite for a picture book creator in a while. It’s a marvelous, almost entirely wordless, and highly unconventional book. My sole objection is the cover. It’s a bit of a pity that it comes off as colorless as it is. And because of the nature of the design, it’s not an accurate depiction of the read since that corner, by definition, has to be in the gutter of the book. But, of course, if it showed the end of the book it would give everything away. A conundrum, indeed.

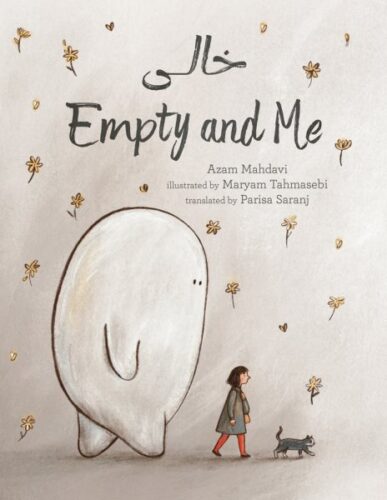

Empty and Me by Azam Mahdavi, ill. Maryam Tahmasebi, translated by Parisa Saranj [Translation – Persian]

We get a fair number of books about grief in a given year. Of those books, almost none come from other countries and cultures. So to receive an Iranian grief book is interesting in and of itself. That is not, however, any guarantee of quality, so it was very nice indeed to discover that together Mahdavi and Tahmasebi have constructed a uniquely thoughtful take on loss. In this story a young girl has lost her mother. As she says, “Then, Mom died, and Empty took her place.” This being a translation, I’d love to hear what other terms could have been used for that word “Empty” here. It’s a very specific choice to use that and not “Sadness” or “Grief” or anything quite like that. In the book, Empty is depicted as a large white blob, two dots for eyes, looking a little like Baymax from Big Hero 6. And Empty isn’t seen as a vicious or mean-spirited companion. We see her holding its hand on the train and going everywhere with it. Then, slowly, the girl’s father begins to insert himself into the story more and more. The book is not particularly interested in investigating his own grief. Honestly, the book isn’t really focused on him at all, he just appears a little more and more as the story continues. Most interestingly, Empty doesn’t leave at the end, or even really change that much except to contain some flowers that the girl put inside of it. It’s such a gentle, caring title. One that refuses to explain too much, leaving a lot of the interpretation up to the reader. One to remember. Previously Seen on the: Message Book List

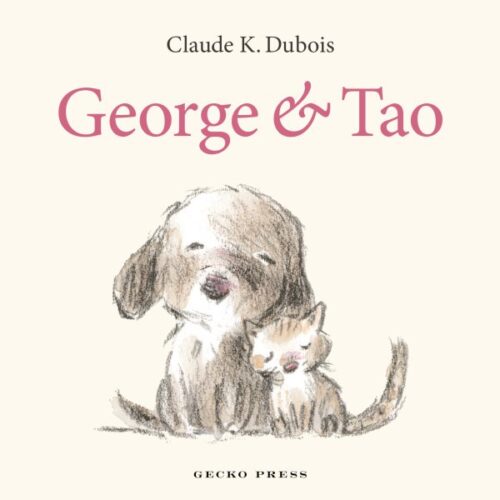

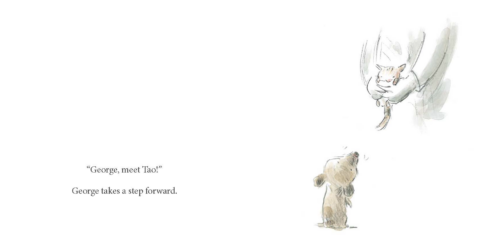

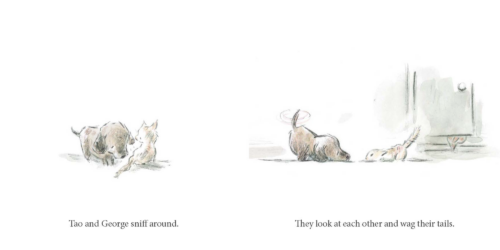

George & Tao by Claude K. Dubois, translated by Daniel Hahn

[Translation – French]

Kind of what you’d get if you blew up two characters from a Sempé cartoon and made ‘em real big. This book is small. Small in format (it clocks in at a mere 6 x 6.5 inches). The characters are small (puppy and kitten). Even the story is relatively small. George is a dog. Tao is a kitten. They are friends but one day Tao gets hurt and disappears for (what seems to George) a very very long time). Tao then comes back. That’s the long and short of it, folks, but let’s not ignore the fact that it is Dubois’s art that elevates the whole kerschmozzle. It’s so incredibly sweet, and remarkable how just a few strokes of a pencil or washes of watercolor can evoke so much feeling. Tiny and rather perfect.

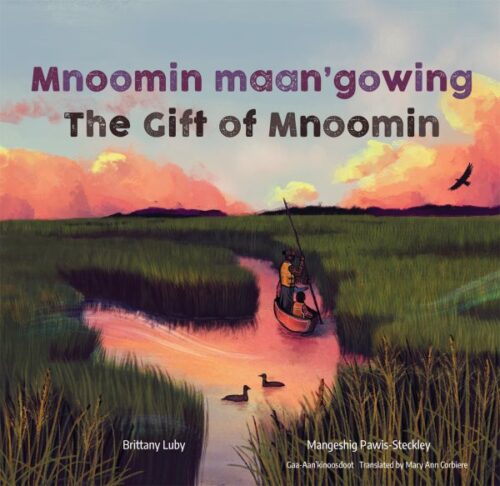

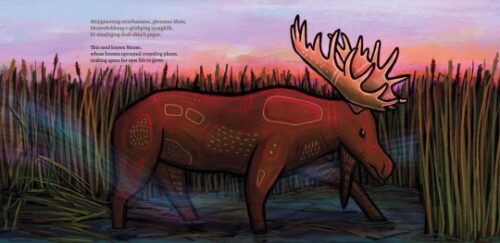

The Gift of Mnoomin / Mnoomin Maan’gowing by Brittany Luby, ill. Joshua Mangeshig Pawis-Steckley, translated by Mary Ann Corbiere

[Translation – Anishinaabemowin]

The ecosystem around the growth of mnoomin is highlighted in this sumptuous dive into the interconnectedness of nature, published simultaneously in English and Anishinaabemowin. Oo! Look at this little charmer. If you’ve a fondness for picture books that highlight the nature and how all aspects rely upon one another, have I got a book for you! The central focus of this book is the harvesting of a plant often mistermed “wild rice”. But rather than make humans out to be the primary instigators of its creation, this story shows how all the different insects, mammals, fish, and birds work together as the mnoomin continues to grow. And the art! Joshua Mangeshig Pawis-Steckley is an Ojibwe Woodland artist and he brings this incredible depth of color and style to all the art here. His sunsets and sunrises alone are worth looking into deeply. Truly beautiful and inconveniently Canadian.

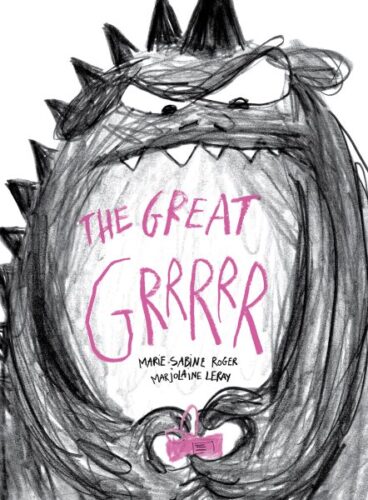

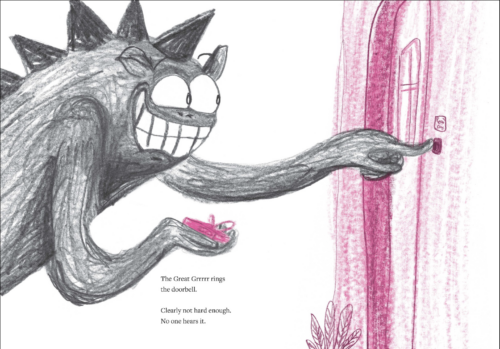

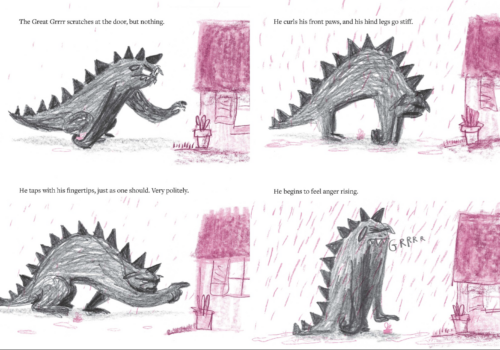

The Great Grrrrr by Marie-Sabine Roger, ill. Marjolaine Leray, translated by Angus Yuen-Killick

[Translation – French]

Who the HECK is Marjolaine Leray?!? I only ask this because I think I’m in love with her artistic style. There is some art in this world so good that you only need to see a glimpse to know how accomplished its creator is. Marjolaine is such a woman. I had seen this book previously in a Myrick Publisher Preview and there was a picture in this book that delighted me. In my preview recap, I summed it up this way:

I don’t know what it was that got to me the most. The eagerness verging on desperation? The sheer toothiness to the toothy grin? Whatever it was, I was hooked, and even more so when I actually read the story. In this book The Great Grrrrr works delivering packages. Unfortunately, while speed may be its primary skill, patience is not. The Great Grrrrr attempts to deliver a package to a house that refuses to open the door and this drives the Grrrrr into an absolute frenzy. A frenzy, that is, until all is revealed. It looks as though Leray is using just graphite and maybe some fluorescent pastels to create this art. I have no idea, but whatever it is it works like a charm. And, best of all, I got to see what its original French name was. You wanna guess? You probably already have: “Le Grand Grrrrr”. Love!

I Can Open It For You by Shinsuke Yoshitake, translated by Lisa Wilcut

[Translation – Japanese]

You know, part of the reason that Shinsuke Yoshitake is as successful as he is at creating picture books is that he’s incredibly good that finding those childhood frustrations and challenges that we adults have all completely forgotten about. For example, the mere act of opening things. We do it all the time, but often kids need help, whether it’s a milk carton or a candy wrapper. In this book, a child fantasizes about all the different things he’ll be able to open when he’s bigger. His dreams start off pretty standard but quickly morph into their most logical extremes (“opening” a politician’s fly or a rock containing ancient bones). What sort of sets this book a little apart from some of Yoshitake’s other works is how it gets a bit touching near the end. The boy’s dad confesses to him that he enjoys opening things for his kid so much because he knows that someday soon he won’t have to anymore. As ever, Yoshitake nails the ending, and I love the more Japanese elements of the book are. From a bath in a home to bowing thanks to your mom when she opens something for you, it may be located in a specific place but it touches on a universal theme. Previously Seen On: The Funny Picture Book List

Kind Crocodile by Leo Timmers, translated by the élami agency [Translation – Dutch]

This one’s definitely more on the upper end of the whole board book spectrum, I have to say, straddling both picture books and board books in its wake. Leo Timmers, of course, is the Dutch vunderkind who can do no wrong on the page. The book pretty much establishes right there with this title that this crocodile is of the sweeter variety. Indeed, when the story opens a plethora of animals come running to him for help, as they escape their natural predators. The crocodile scares each hungry baddy off with an appropriate “GRRRR” even as the animals he saves start to create a kind of Bremen Town Musicians stack on his back. Timers utilizes a limited number of words and his usual palette that looks both two and three-dimensional at the same time. Not sure how he does it, but by gum I hope he never stops. Previously Seen On: The Board Book List.

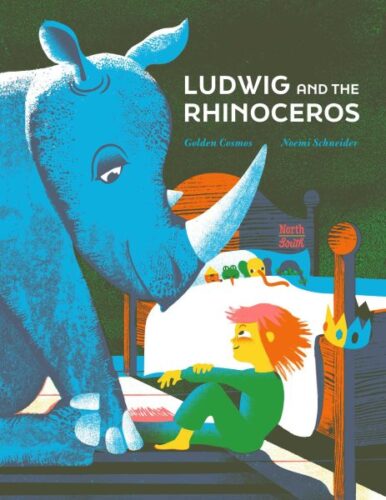

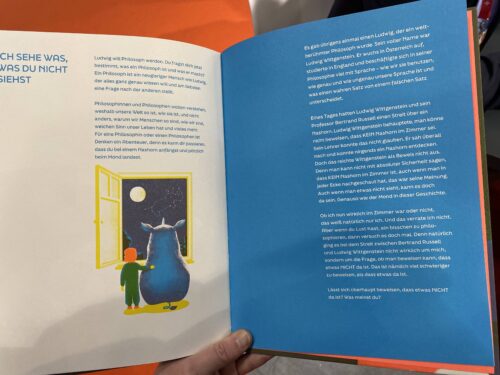

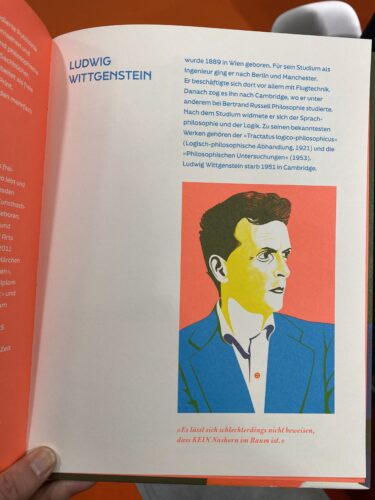

Ludwig and the Rhinoceros: A Philosophical Bedtime Story by Noemi Schneider, ill. Golden Cosmos, translated by Marshall Yarbrough

[Translation – German]

Ahh. One of the few books I first saw at the Bologna Children’s Book Fair that actually made it to the States. Do you need some concrete reasons why we need to see more translated children’s books on our nation’s shelves? Here’s one: How often in America are philosophical suppositions by Ludwig Wittgenstein turned into picture books? The conceit behind this is delightful. Apparently, Wittgenstein and his professor Bertrand Russell (another name you don’t usually see in books for 5-year-olds) got into an argument about whether or not there was a rhinoceros in the room. As the book’s backmatter explains, “Ludwig claimed that you couldn’t prove that there was NOT a rhinoceros in the room.” You can’t prove a negative. This idea is taken to its logical extreme here, with the story of a kid named Ludwig who tells his dad that there’s a rhino in his bedroom. No matter where dad looks, it’s never where the rhino is. The art, by duo Doris Freigofas and Daniel Dolz under the truly awesome name of “Golden Cosmos” (we should pair them with Red Nose Studio one of these days) use only three fluorescent colors to print the book. As it says at the end, “Three special luminous colors that mix when printed on top of one another. In this way three colors become seven colors.” The result has a classic feel but with mighty contemporary colors.

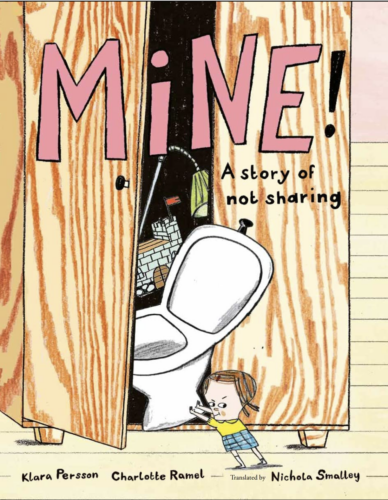

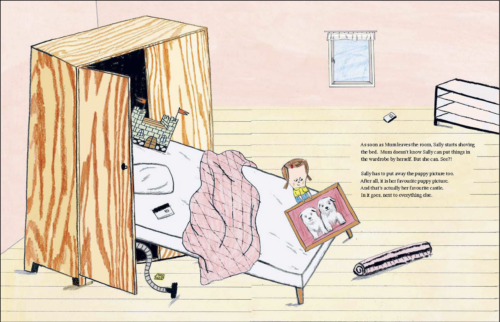

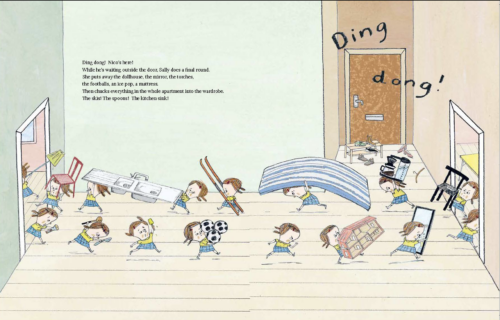

Mine! A Story of Not Sharing by Klara Persson, ill. Charlotte Ramel, translated by Nichola Smalley

[Translation – Swedish]

We have all been Sally at some point in our lives. Sure, the whole concept of sharing sounds great on paper, but when push comes to shove and you actually have to do it? Count me out!! Sally’s friend Nico is coming over to play and right from the start Sally informs Mom that there is no way in the world that Nico’s going to play with her stuffed squirrel. Her mom, being a patient and logical soul, suggests putting the squirrel in the wardrobe until Nico’s gone. Unfortunately this well-meaning suggestion just gets Sally started. If the squirrel can go in the wardrobe then so can her train. And her car park (love that translation). And her fish you catch with a fishing rod. Then things start to get extreme. In goes her bed! Her bathtub! Her mom!! And even when Nico comes she doesn’t stop because what if her friend Eva came by and wanted to play with HIM? Into the wardrobe goes Nico! It’s only when Sally hears how much fun everyone’s having in the wardrobe without her that she relents and lets everyone and everything out. Persson ratchets up the humor by taking Sally’s instincts to their logical extreme. Meanwhile Ramel knows how to give this already spartan (compared to a couple American houses I know) home a real thorough emptying out. Sharing may be caring but hoarding isn’t boring. Forgive me. Previously Seen On: The Funny Picture Book List

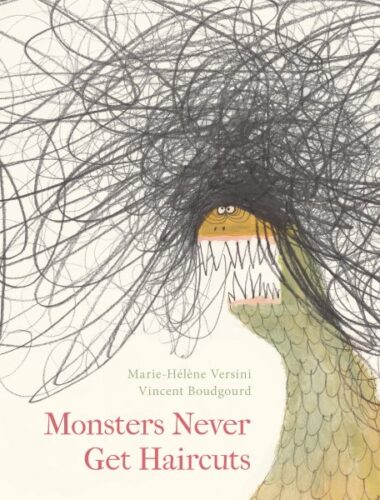

Monsters Never Get Haircuts by Marie-Hélène Versini, ill. Vincent Boudgourd

[Translation – French]

I’ve been making TikTok videos this year for the first time and though I haven’t done anything with this one in particular, if I were to make a video of it, it would probably consist of me holding it up and comparing the DO on the cover to my own. As covers go, this may be one of my favorite picture book jackets of 2023. Boudgourd is just having a ball with his socially inept monster subjects. The book is written almost entirely in the negative, explaining what it is that monsters do not do. They don’t go to the dentist, or wear glasses. They don’t swim and they certainly aren’t afraid of the dark. Now as you’re reading through this, you’re mostly just enjoying the sheer array of monsters on display on these pages. The white of the page serves as the backdrop to their antics. You begin to wonder how Versini will choose to end the book. She has an array of options before her, but I like her particular solution. Near the end you see a big pink monster with sharp pointy teeth explaining to a child peeking out from under some bedsheets, “Monsters aren’t like this. Monsters don’t do that. And do you know why?” Turn the page and the final image is of the kid, smiling sweetly in a bed, no monsters in sight. “Because monsters don’t exist”. Lives up to its premise.

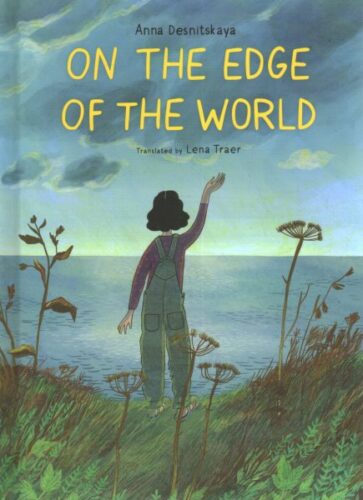

On the Edge of the World by Anna Desnitskaya, translated by Lena Traer

[Translation – Russian]

What could be more unconventional than a title where its two storylines meet in the center of the book? Loneliness is the name of the game here. Depending on how you hold this book, you can chose to begin by reading the story of Vera, a girl living on the eastern coast of the Kamchatka Peninsula in Russia. Determined to someday be a ship captain, Vera goes about her day playing and pretending she had a friend to share all her knowledge with. At the end of her story she takes a flashlight and points it out over the dark water, using morse code to say, “Hi, I’m Vera.” And the, suddenly, she sees a response. “Hi, I’m Lucas.” Now flip the entire book upside down and meet Lucas himself! He’s a lonely kid too and currently lives in Santiago, the capital of Chile. Like Vera he spends the day playing but he wishes he had a friend. So at night he turns his flashlight across the sea . . . and you know the rest. There’s no true conclusion to this story but in the center of the book you can watch the beams of light impossibly splay out over different oceanic scenes. There’s a gentle melancholy to the book but there’s also a great deal of hope in there as well. The tone is so key to its success, and to that we must credit Lena Traer, translator extraordinaire. Consider this a writing prompt book, or a title where you can get kids to tell the rest of the story. However they want to tell it.

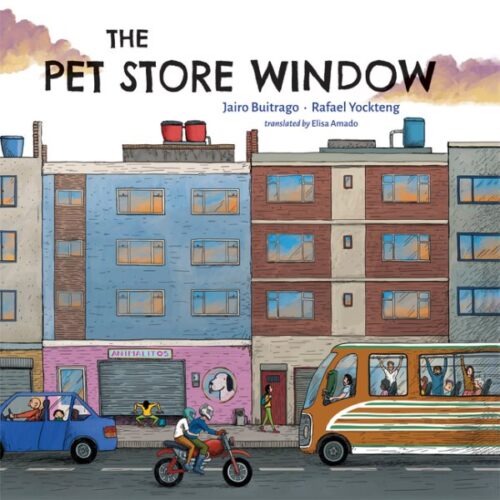

The Pet Store Window by Jairo Buitrago, ill. Rafael Yockteng, translated by Elisa Amado

[Translation – Spanish]

I think we’re going to have to come up with a word for what precisely to call books by Buitrago and Yockteng. They seem to have carved out a very specific little niche for themselves in the vast pantheon of picturebookdom. No one really does what they do either, and I think a lot of that comes down to tone. They have such a distinctive vibe in all their books. Take Pet Store Window as a perfect example. I was just coming back to this book after having read and enjoyed it a week or two prior, but when I opened it up I was surprised to see that it had words. I don’t know why, but I remembered it as having been a wordless book. The story is about a dog that nobody wants at the pet store. “He was a dog. A normal, regular dog, not too big, not too small. Not that smart and not very handsome, either.” Anna is the woman who works in the store and you can tell pretty early on that she doesn’t get paid enough. It’s not just the dog that never gets adopted either, but also a mouse and a hedgehog. When the store is closed but she can’t get the animals to be taken in by anyone, she actually goes to the pet store owner’s house and you have this WONDERFUL shot of him looking bored as hell as she yells at him, and inside there’s a swanky party he would much rather be getting back to. Is there a happy ending? Of course there is! But truly, I love the translation of this almost as much as the art and story. “The store owner didn’t care what Ana did. Because there are people who don’t care what happens to others.” Preach it, Buitrago.

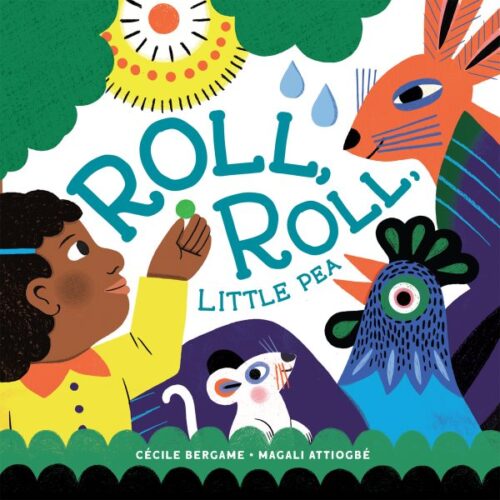

Roll, Roll, Little Pea by Cecile Bergame, ill. Magali Attiogbe, translated by Angus Yuen-Killick

[Translation – French]

Did anyone else grow up listening to the cassette tape of “Wee Sing Silly Songs”? That whole chunk of my childhood takes up residence in large portions of my brain to this very day. In any case, I ask this mostly because there was a song on that tape mighty familiar to many kids that have ever done summer camp: “On Top of Spaghetti”. The song is about a wayward meatball that escapes being devoured. This is very in keeping with the plot of this particular book as well, though instead of it being about a wayward meat product on the run it’s about a small pea. I will tell you all right here and right now that since this book is a translation I approached it with trepidation. Not all translations are created equal and I was concerned that perhaps this book wouldn’t read aloud particularly well. Turns out, my fears were completely unfounded. Filled with incredible, vibrant colors and hues, the words on these pages are delightful. Once the pea has made its escape the text reads something like, “Roll Roll, Little Pea, along the floor and under the stairs”, (always changing where it heads) and on the opposite page is some kind of critter who would like to crunch or nibble or peck or even “Devour” the pea. With pictures you can make out across a room and that steady diet of repetition, the end result is a great readaloud and stellar translation. Two thumbs up! Previously Seen On: The Readaloud List

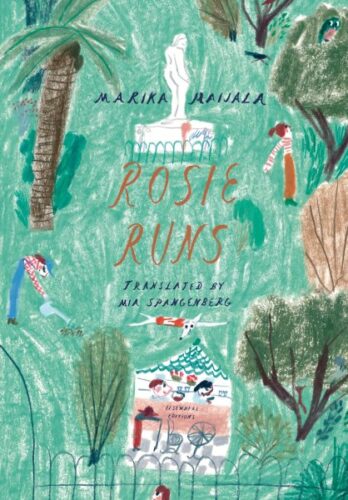

Rosie Runs by Marika Maijala, translated by Mia Spangenberg

[Translation – Finnish]

On occasion, a translated work is a breath of fresh air in a sea of picture book sameness. I had the distinct feeling that I’d seen a picture book along the lines of Rosie Runs before when I picked this title up, but after a few pages that feeling dissipated entirely. Clocking in at an impressive 13” x 9”, the book has the same feel as a Ludwig Bemelmans title. It follows a white greyhound named Rosie who escapes the confines of her dog racing life and flees into the wider world. In an American book this would end with a pat little ending where a kind child ultimately befriends and adopts Rosie. This book, however, has no interest in trapping its titular character any longer. She finds other dogs at the end, absolutely, but for her it’s the spirit of running that infuses the storytelling. I couldn’t help but pair it in my mind with this year’s longer spiritual kin, the middle grade novel The Eyes and the Impossible by Dave Eggers. In both cases you’ve a canine running faster than the wind itself. Winner of the Rudolph Koivu Award, I suppose you might even go so far as to call the book a metaphor. What I can say is that it’s an original that just feels good to read.

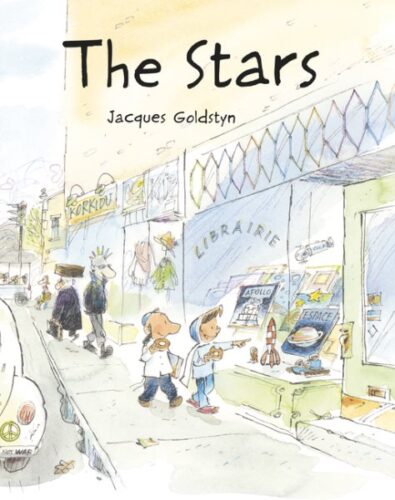

The Stars by Jacques Goldstyn, translated by Helen Mixter

[Translation – French]

Yakov loves space. Aïcha loves space. A sublimely sweet story about how our passions bring us together. Wow! It’s like Sempé all over again! This little French-Canadian import is sort of what I wish folks understood about portraying a range of different voices and perspectives in children’s books. You’ve got two kids from two different cultures, both completely obsessed with space. It’s a love story, sure, but it’s also a story about how things change and how if you follow your passions, that is the right choice in the end. I loved the jokes and the art and the little details, like that final shot of their entire family’s feet. An utter charmer.

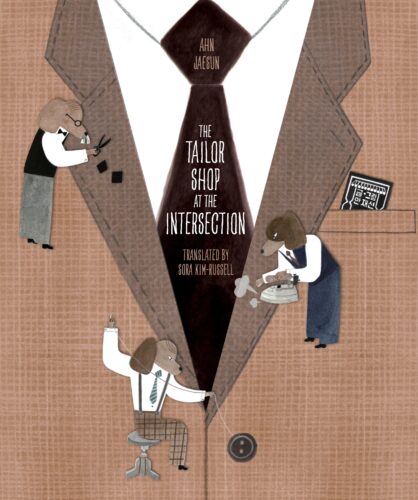

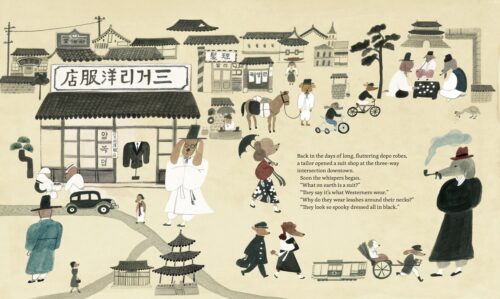

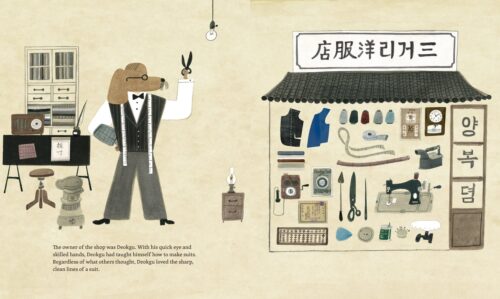

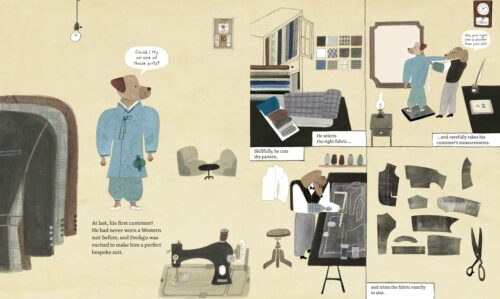

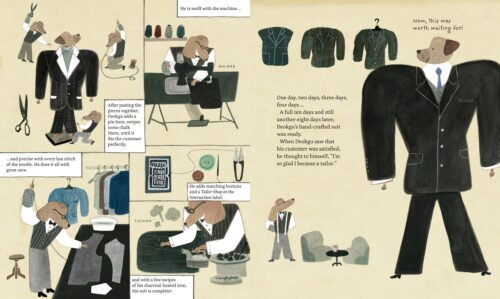

The Tailor Shop at the Intersection by Ahn Jaesun, translated by Sora Kim-Russell

[Translation – Korean]

At the end of this book, author/illustrator Ahn Jaesun has including the following statement: “I always thought it would be wonderful to have a favorite place that I could go back to again and again with my two sons, and with their children as well in the future. The Tailor Shop at the Intersection was inspired by that idea.” Now this book is an excellent example of an import that we Americans may read but will only understand partially. Back in April I interviewed Adam Levy and Ashley Nelson Levy, the duo behind Transit Books, and they discussed this title. At the time I said of it, “The book is a kind of statement about urban development, capitalism, and artisanal craft.” In the course of our talk, they mentioned some of those details I just alluded to. You see, this is a book about three generations of dogs who are also tailors and who specialize in Western style business suits”. … when Transit acquired the book, it was the translator who pointed out that when you look at the city’s signs there is a subtle but significant shift over time. Initially, the signs display Chinese long words that were more common in the 20th century. Then, as time goes by, the script changes in a way that would be familiar to Korean readers. At Transit, they felt it was important to preserve that element of the book. As they described it, a publisher has as much power to erase cultural specifics as to highlight them. For Adam and Ashley, though, there’s little point in a translation unless you make sure that you’re not whitewashing or domesticating the spirit of the original.” As for the final product, once I saw it firsthand I was utterly charmed. It really doesn’t feel like any other book I’ve ever seen, but it’s the tone that stays with you. It’s soothing. Like a warm bath you just kind of sink into.

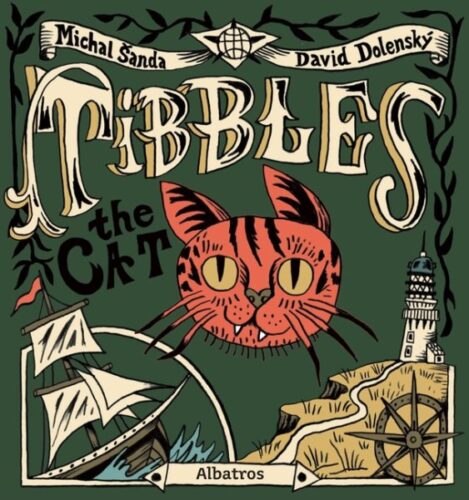

Tibbles the Cat by Michal Šanda, ill. David Dolenský, translated by Mark Worthington

[Translation – Czech]

When a new lighthouse keeper takes a position on a remote island in New Zealand, he’s surprised when his kitty cat brings home a new kind of bird. Based on a true story, this is technically the tale of an adorable invasive species. The book does an amazing job at showing how just one little innocent kitty cat in the wrong place at the wrong time can cause massive destruction to a previously untouched ecosystem. It’s funny because I truly wasn’t thinking about that when the book went on. Instead, I found myself cooing over how nice it was for the cat to have a whole island to explore. More fool me. This title beautifully hammers home how our good intentions can wipe out entire species when we’re not paying attention.

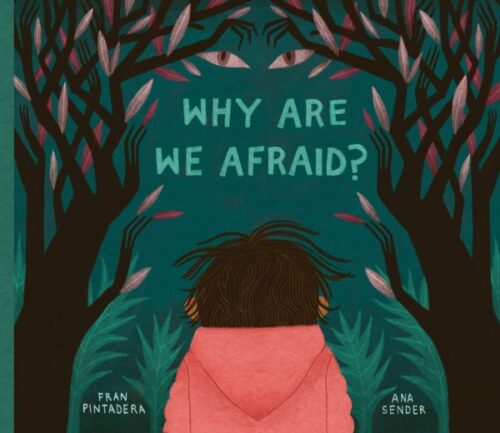

Why Are We Afraid? by Fran Pintadera, ill. Ana Sender, translated by Mihaila Petricic

[Translation – Spanish]

Fear gets a proper treatment in a rather lovely Spanish import. It’s interesting that often when I see Spanish nonfiction titles for children brought to the States I don’t see a lot of backmatter. Then here we have this nice little fictional picture book and voila! Backmatter galore about “the original fear”, “the types of fear”, “the lessons behind our fears”, “the masks of fear”, “the appeal of fear”, and finally some activities for talking through fears with kids. All this makes the book sound a bit like one of those purposeful books, but the title is quite an artistic endeavor more than anything else. Lovely, deep, and sumptuous art tells the story of Max who asks his father, “Dad, have you ever been afraid?” It’s an interestingly evocative story full of deep-seated fears brought to life. I think that a kid could get quite engulfed in a book of this sort. The message may stay with them, but it’s just as likely that the images will. My personal favorite is the two-page spread where Max is seen with wings staring up at flying people, a ball and chain attached to his leg while the text reads, “Often we’re afraid of freedom, strange as it seems.” A more artistic rendering of something all children, on some level, know very well. Previously Seen On: The Message List

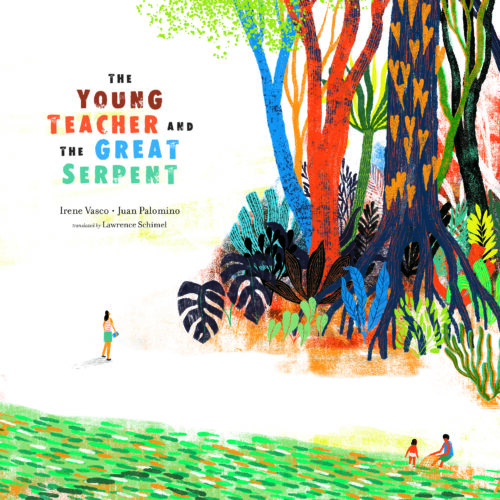

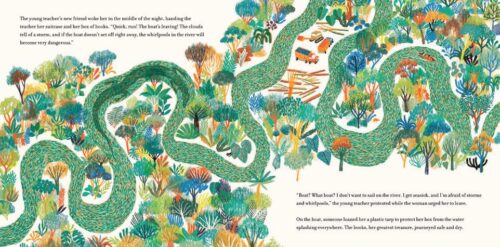

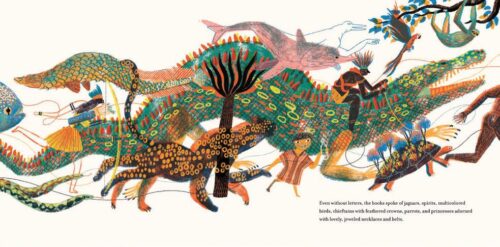

The Young Teacher and the Great Serpent by Irene Vasco, ill. Juan Palomino, translated by Lawrence Schimel

[Translation – Spanish]

I’m getting mild Anno vibes from this, though I think that’s simply a response to the size of the characters themselves. The story is nothing the same. There’s a theory out there that you won’t see a picture book about an adult unless it’s nonfiction or the adult is a furry animal that wears clothing. Obviously in situations like Miss Rumphius this is not the case, but it’s true that they don’t happen as often as all that. This title is different. There’s a reality that I enjoyed behind this book, though, that I think kids will dig as well. It doesn’t hurt that Palomino has drawn these remarkable vistas on each page. I’m admittedly a little fascinated by what this book is doing with distance. You view all the happenings from a great height or distance, and it gives you a kind of omnipotent feel over the proceedings. Sometimes you get a bit closer, but that’s when you’re viewing story characters and not real people. That the art itself is frame-worthy, whether it’s lightning or the rage of a swollen river, is beyond question. Oh, and the story? A young teacher comes to a difficult to reach part of the Amazon on her first assignment. She also comes with a load of assumptions that may be somewhat upended with the help of nature itself. Just lovely. Juan Palomino is a Mexican artist and you can find an interview with him here. Previously Seen On: The Caldenott List

Hope you enjoyed these! Here are the lists you can expect for the rest of this month:

December 1 – Great Board Books

December 2 – Picture Book Readaloud

December 3 – Simple Picture Book Texts

December 4 – Transcendent Holiday Picture Books

December 5 – Rhyming Picture Books

December 6 – Funny Picture Books

December 7 – CaldeNotts

December 8 – Picture Book Reprints

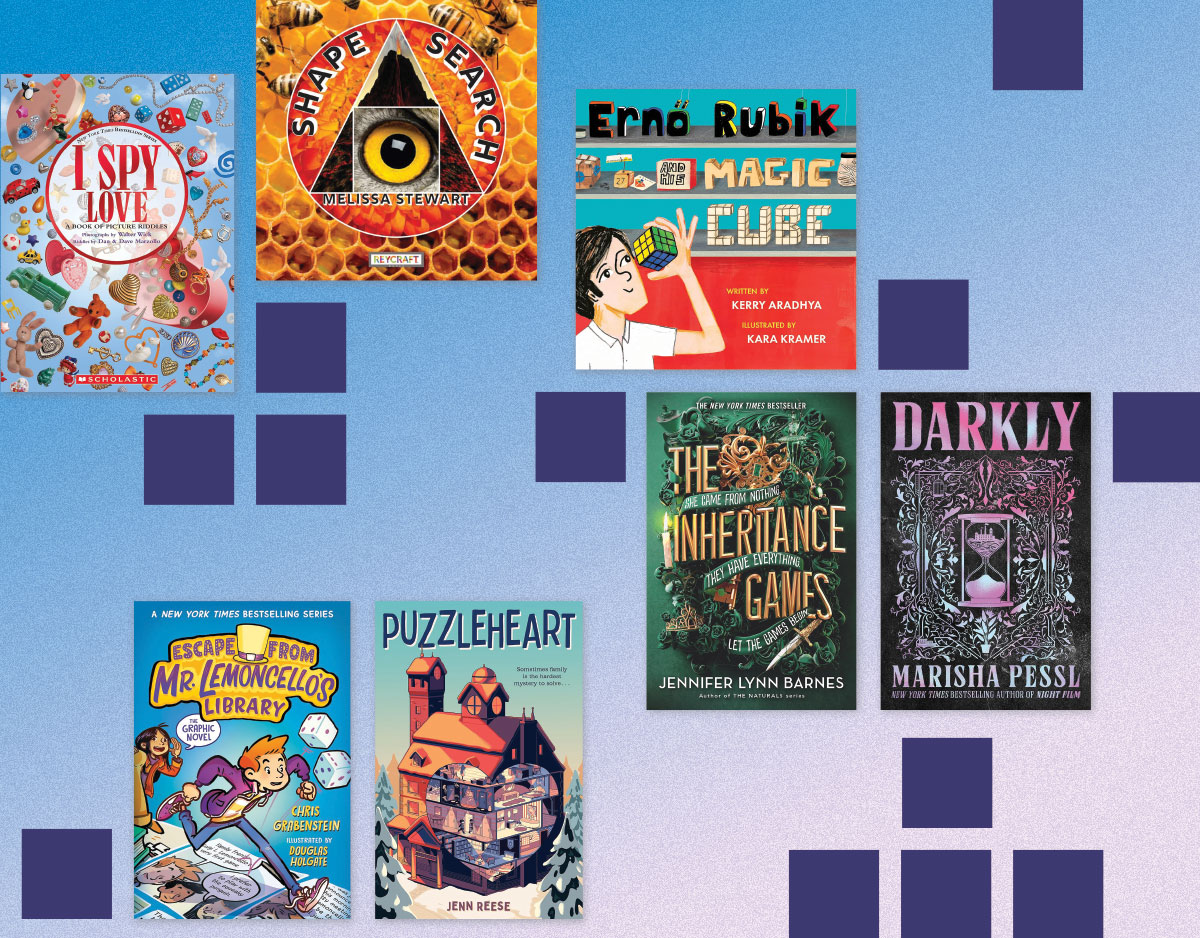

December 9 – Math Books for Kids

December 10 – Gross Books

December 11 – Books with a Message

December 12 – Fabulous Photography

December 13 – Translated Picture Books

December 14 – Fairy Tales / Folktales / Religious Tales

December 15 – Wordless Picture Books

December 16 – Poetry Books

December 17 – Unconventional Children’s Books

December 18 – Easy Books & Early Chapter Books

December 19 – Older Funny Books

December 20 – Science Fiction Books

December 21 – Fantasy Books

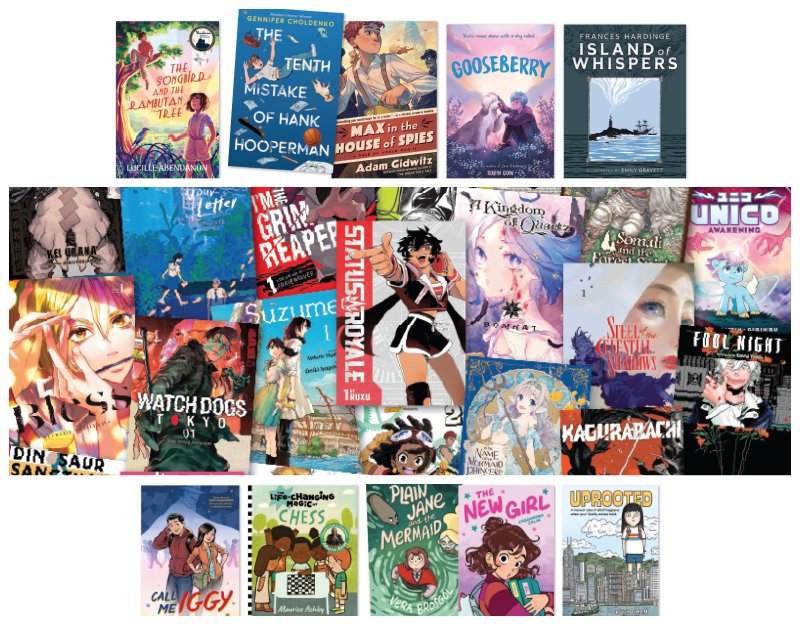

December 22 – Comics & Graphic Novels

December 23 – Informational Fiction

December 24 – American History

December 25 – Science & Nature Books

December 26 – Unique Biographies

December 27 – Nonfiction Picture Books

December 28 – Nonfiction Books for Older Readers

December 29 – Audiobooks for Kids

December 30 – Middle Grade Novels

December 31 – Picture Books

Filed under: 31 Days 31 Lists, Best Books, Best Books of 2023

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Magda, Intergalactic Chef: The Big Tournament | Exclusive Preview

Fifteen early Mock Newbery 2026 Contenders

When Book Bans are a Form of Discrimination, What is the Path to Justice?

ADVERTISEMENT

What a diverse collection today. Heaven would be sitting down to a table and having time to explore each one. Obviously “enough” are written, illustrated, and published in American to take care of the our need for new titles each year, but oh, how wonderful it is that we also have an opportunity to explore contributions from all over the world. The cover of MONSTERS NEVER GET HAIRCUTS is so fabulous. TIBBLES THE CAT might be a perfect companion to a non fiction scientific book about invasive species.

Yes, my library’s Blueberry Award committee is considering TIBBLES seriously for that very reason.

Just learned of this:

SLJ Webcast FOUND IN TRANSLATION

Dec. 14. 2-3 pm ET