The Editorial Director and the Translator: A Talk About EBYR’s Stories from Latin America with Kathleen Merz and Lawrence Schimel

If you saw the news this week then you know that Simon & Schuster has just been acquired by private equity firm KKR for $1.62bn. But as we watch large firms acquire massive publishing companies, the experience can be a bit like watching sharks devour sharks. Meanwhile, elsewhere, it doesn’t take much effort to notice that it’s the small publishers doing the innovative, interesting, imaginative work that makes the American children’s book scene as vibrant and interesting as it is today.

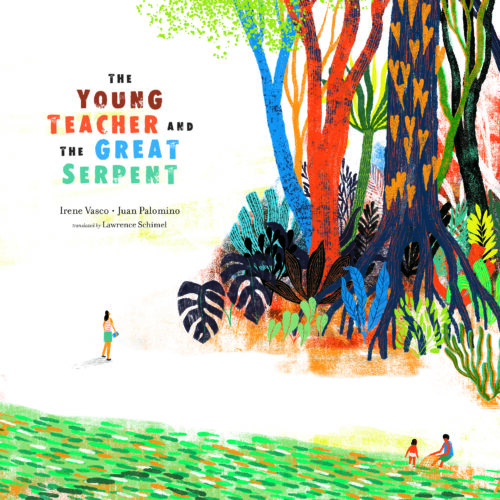

Today, I’ve the very great pleasure to be talking with Eerdmans Books for Young Readers Editorial Director Kathleen Merz alongside award-winning translator, Lawrence Schimel. Together, they’ve agreed to talk to me about the EBYR Stories from Latin America series that’s coming out this year. Anchoring this launch are three frontlist titles (Colorful Mondays, On the Edge of the World, and The Young Teacher and the Great Serpent).

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Now here’s the thing. You folks know me. And if you know me then you know that I don’t really care if you’re a big publisher or a small publisher as long as the quality of your books is there. And these three books? Some of the best I’ve seen this year.

Let’s find out where the heck they came from:

Betsy Bird: Kathleen! Lawrence! What a delight having the two of you in conversation today! And, to be perfectly frank, these three books are amazing. There are certain publishers that I read immediately when I receive their books. Eerdmans falls into that category. So just to kick us off right from the start, I’d love it if the two of you could talk about how you came to discover these titles. Or, in your case Lawrence, how you were approached to translate some of them.

Lawrence Schimel: I’ve been translating for Eerdmans for years now. Another translator they have worked with for years—Laura Watkinson, who translates from Dutch, German, and Italian—recommended me when they had a title to translate from Spanish. And we’ve now worked on a dozen projects together.

Often, they’re books that have come to Eerdmans’ attention via literary agents or foreign rights directors; although, if I see a book I think might appeal, I’ll also bring it to their attention. And it sometimes works the other way. I had a feeling that one of Eerdmans’ titles, Building an Orchestra of Hope by Carmen Oliver and Luisa Uribe (written in English but set in Paraguay), would appeal to some Spanish publishers I know. So I asked to pitch it on their behalf and brought the project with me to the Guadalajara Book Fair. Everything worked out, and now my Spanish translation is coming from Juventud in October.

Publishing can sometimes be a small world, especially in the case of my longtime friend Irene Vasco, author of Eerdmans’ The Young Teacher and the Great Serpent (Oct. 10). I’ve translated into English another title by her, Letters in Charcoal (Lantana), also illustrated by Juan Palomino. A handful of her titles were originally published by Ekaré, who also published one of my own picture books as an author, ¡VAMOS A VER A PAPÁ!, illustrated by Alba Marina Rivera and translated into English by Elisa Amado.

And even though we each came to the project separately, Eerdmans will be publishing What Makes Us Human by Victor DO Santos and Ana Forlati (Spring 2024), which I had already translated into Spanish for La Maleta Ediciones in Spain. Coincidence, perhaps, or another confirmation of being on the same “wavelength” and, therefore, why we work together so well.)

Kathleen Merz: Thanks for your very kind words about our books—and for giving us the chance to talk about them with you!

The answer to your question about how we came to discover these books is very much as Lawrence described: We review many, many projects each year from literary agents and foreign rights directors who represent publishers around the world. A few of them make the cut—most of them don’t.

On the Edge of the World came to us from a literary agent we’ve worked with for years on a number of previous titles. She represents Anna Desnitskaya directly, along with a number of other talented creators.

Colorful Mondays and The Young Teacher and the Great Serpent both came to us from a rights agency that was familiar with our program and reached out to me a couple years ago. They represent Editorial Juventud, the books’ original publisher.

We’re always looking to make new connections and continue exploring the publishing work that’s being done around the world. Those connections often make for the best opportunities: when an agent or a translator knows us and our publishing house well enough to be able to say, “This could be an Eerdmans book.” Relationships like the one we have with Lawrence—where we know and respect his work, know that he has a good sense for what kind of books we do, and also just generally love working with him—are such an important part of the process of finding books to publish.

Sometimes there’s a great feeling of serendipity to the discovery process, too. In the case of the other book that Lawrence mentioned, What Makes Us Human, the author actually approached me directly. He was a fan of our publishing house, and he’s a linguist—so it caught his attention that linguistics is a passion area of mine. And he was absolutely right that a book about the importance of language, and how it connects us all as humans, was the perfect fit for us.

As Lawrence says, publishing is often a small world, and international publishing is definitely a specific niche within that—even as it reminds me every day how wide and varied and surprising (often in the best possible ways) the global landscape is, in books and beyond.

BB: Each of these three books is so different from the other two. Certainly they all originate from Latin America but in terms of tone, content, and voice they vary vastly. Lawrence, how do you capture that ineffable quality when you translate? How do you vary tone?

LS: My philosophy with translations is always to recreate the reading experience. So if one book has a voice that uses a sophisticated vocabulary, say, or maybe lots of word play, I would try and recreate that in the translation as well. I say recreate, because it often isn’t just a one-to-one substitution. So a pun may not work in the translation, but maybe a different one can be used in the same place or on the same page. And voice can also be a question of sentence structures, or even sentence lengths, not just word choices. So even if I am the same translator for books from Chile, Honduras, Colombia, and Spain, they shouldn’t all sound alike in English, even though they’re all in “my” English.

For the two most recent Eerdmans titles I translated, Colorful Mondays and The Young Teacher and the Great Serpent, they’re both about the joy of reading and books but each with a very different voice and tone. Colorful Mondays is from the point of view of a young boy whose life is filled with joy each week when the bibliobus arrives, and we tried to reflect that in the language used. We often flipped syntax around, or broke long sentences into two shorter ones, to keep the focus on the joy that books brought to the whole village.

The Young Teacher and the Great Serpent, on the other hand, has a slightly “older” feel to it, with language that is richer in texture and description (the title itself is a perfect example). A young teacher on her first assignment after graduating, who dreams of bringing literacy and books to a remote Amazon village and winds up learning as much or more from her students. So the language choices likewise reflect this: “journey” instead of “trip,” etc.

BB: Kathleen from an editorial perspective, what is your role when editing these works? Is it simply a case of selection or is there editorial work done when these books come to our shores that people wouldn’t necessarily know about?

KM: My role varies a great deal from book to book. Every book has its unique set of needs and challenges.

The process does always begin with the selection, of course. I consider myself very lucky to get to see the wide range of titles that cross my desk for review. As is ever the case in publishing, of course, we end up saying no to the vast majority of projects we look at. We’re asking lots of different questions at that stage: What makes this book stand out from others like it? Does it fit with the other titles on our list? What’s the quality of the illustration? What’s the quality of the writing? To help evaluate that, it’s common for us to ask a translator to take a look—it’s more than a bit tricky to judge writing quality for a language you don’t speak!

We’re also looking for books that will work for a US audience. To me, that means that a book speaks to something universal about the human experience, even when it’s coming from a very different cultural landscape than our own.

After we acquire rights to a book, that’s when the editorial process can really start to vary. Sometimes, there’s relatively little work involved: the structure of the book is working, the art and the text and the design are all working together seamlessly, and the text is relatively easy to translate and so the translation comes in with very little need for edits (That’s one of the beautiful things about working on books that have already been published in another country: they’ve already gone through the editorial process once). Of course, even in those ideal circumstances, there’s almost always at least a little back-and-forth with the translator, making sure that every word and phrase is working as it needs to, in a way that feels consistent across the story and appropriate for the intended reader.

Sometimes, editorial work on the translation is a bit more involved. There might be a particular tone in the original that the translator is working to capture, or maybe there’s wordplay that doesn’t translate neatly to English. Or maybe there are cultural details that we need to figure out how to make intelligible to a US audience unfamiliar with them—without overexplaining in a clunky way that pulls the reader out of the story.

Occasionally, the changes we make to a book are even broader than that. That’s less common—we always want to respect the original version of the book, and the creators’ vision for it, as closely as we can. If there are too many issues we feel would need changing, we’d be unlikely to take the book on in the first place.

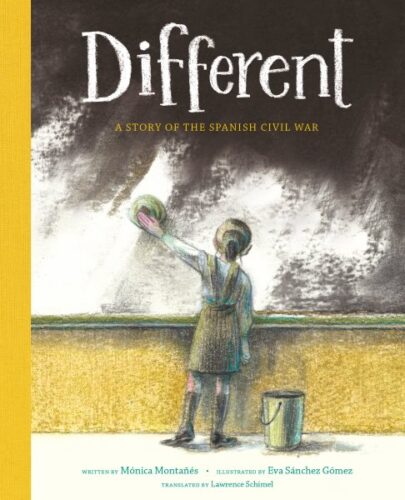

But if we are in love with a project otherwise, and can see a way forward, we might ask the originating publisher if we can make some changes to a book on more of a macro level—usually either because we feel the story would be better served by doing so, or because we feel it would land better in the US market. Lawrence describes below a great instance where we made changes on that broader level: For our book Different: A Story of the Spanish Civil War, he suggested shifting the format slightly so that we were positioning it as an illustrated middle grade novel, rather than a picture book—which was a much better match between subject and intended age range for readers in the US. We loved that book from the first time we looked at it, but it wasn’t until Lawrence made his suggestion that we could really see a way forward to make it work for a US readership.

No matter what editorial (or design, but that’s another conversation!) changes we’re making, it’s always a conversation—with the original publisher, with the book’s creators, with the translator.

BB: Lawrence, was there anything particularly challenging about translating these titles? Anything that caught you unawares?

LS: There was one project where the point of view actually shifted, in the original, away from our protagonist to other characters in the book. Kathleen and I kept struggling with what to do with those lines, and nothing was working. When I pointed it out to Kathleen, having finally identified the underlying problem, we decided to switch some narration to dialogue so we were able to keep all the content but make it coherent internally for the English edition. And actually, the author, on reading the translation, said they’d change later printings to make the same changes in the original.

BB: Of the three books, ON THE EDGE OF THE WORLD is, in many ways, the most ambitious. It’s two stories in one that intersect. Kathleen, what was your first impression when you encountered this book?

KM: It was love at first sight with this book. I think my first thought was probably, Oh, I hope we get to publish this one.

Often when we review books, we’re looking at fairly rough translations. But the text for this book was actually quite clean when it came to us—I’m not sure if the author had written or translated the book into English herself, of if the agent had helped to make the materials ready for presentation. Either way, it was a more seamless reading experience than usual. I’m sure that even if the text had been really rough, though, I still would have fallen in love with this story just from the art and the concept alone.

I’m always a little skeptical of books that play with format like this—a book you flip to read from either side. It can often feel like a gimmick more than anything else. But for this book, the form absolutely reinforces and is integral to the story. You almost end up reading Vera and Lucas’s stories in a circle—you finish one character’s story, you flip back around to the other’s. They’re two characters circling each other around the globe, looking for that point of connection between them.

And the themes of this book are so deeply relatable. The loneliness, the deep longing for connection, the desire to see and be seen for all the little things that we love and all the ways we spend our days—all of these ideas at the heart of the book speak so profoundly to experiences that we humans have, no matter what part of the world we live in.

I mentioned above that we’re always looking for books that speak to something universal about the human experience, even when they’re coming from different cultural landscape. One of the truths of good writing is that the more specific a story is, often the greater the emotional resonance it carries. Readers typically don’t want stories that offer vague generalizations—that’s not how we encounter the world. This book is such a beautiful example of that. On the Edge of the World is bursting with delightful specific details that bring Vera and Lucas’s worlds alive: morse-code messages and syrniki breakfasts and ammonite fossils and tree branches that are perfect for settling in with a good book—with plenty of room for a friend, if only we could find that friend.

Life in other countries may have different textures, different scenery, different foods, different struggles—but we as humans all have so many more things in common with each other than we do differences. That’s why we publish books from other countries, that’s why we have a series like this one—to remind us of all the connections that are there if we only look, of all the stories running parallel to each other, waiting and hoping that someday they’ll get to intersect.

BB: Lawrence, I wonder if you could walk us through your process a little. When you encounter a book in need of translation for the first time, how do you tackle the job?

LS: So there are two separate things: one is when I find a book, and the other is when I am asked by a publisher (or maybe an author or their agent) to translate a book. In the first case, it’s pretty easy because I am a voracious reader and I fall in love with books and want to help get them into the hands of more readers. Those are the projects I’m often pitching to publishers. In those cases, I already have an idea for how I’d translate them, because I’ve read them already and have fallen in love with them. And usually I can already hear the voice in my head of how I’d translate it, even if a lot of decisions can’t actually get made until one has one’s hands in the dough, as it were.

In the latter case, I work slightly different, especially for novels, because I prefer to start translating before reading. Obviously, I’m producing only a rough draft with this first pass, but I find I work faster if I haven’t read the book yet because I want to find out what happens next. In any project, the first bit one translates always needs quite a lot of revision because it often takes a while to settle into the voice of the book. That’s why for longer novels, I often recommend starting not at the opening but somewhere in the middle (what some writer friends call the “muddle”) so when you’ve hit your stride, you can go back and tackle the crucial opening sequence and continue on from there. And when you hit the bit you’ve already translated from the middle, you can revise it and carry on.

BB: Finally, could you tell me a little bit about how the two of you work together? What is the nature of the relationship between an editor and a translator on a book? This isn’t something a lot of us hear about, after all.

LS: I think we’ve developed a great rapport over the years, especially since for both Kathleen and myself there is no ego involved as to whether it was my translation or her edit. Instead, we both care about making the book as good as possible in English, as we can help it to be. So I will flag things sometimes as I’m going through my initial draft, as there may be issues that are less about the translation itself and more something requiring editorial decisions. And when I get Kathleen’s first round of edits back, there are times when I’ll be like “oh, that’s so much better now” but there may be others where I’ll decide the edit changes things too much and I can see how what I’d had originally was confusing or wasn’t quite right and will suggest a third option that we both agree on. This process sometimes goes through a handful of back and forths, too–after which I’ll usually go back to the Spanish and see if we’ve strayed too far from the original meaning.

The important thing, I think, is that we both trust one another. And we both care about making the book be as good as it can be for English readers.

In the case of Different, written by Mónica Montañés and illustrated by Eva Sánchez Gómez, it was originally published as a text-heavy picture book. But I suggested that in English, it would match better with reader’s expectations for that age group to increase the font size (and also the page count) and to publish it as a middle grade novel—keeping all the same art, just giving more space for the text. I likewise advocated for keeping some terms in Spanish and creating a glossary at the end. Kathleen agreed to both and also added some cultural context for the English edition to help readers understand the background of the novel. And it went on to win a Batchelder Honor among other awards! But that was only possible because we trusted one another, so that when I made some proposals that went beyond just the translation of the text of the book, she listened to me, and we discussed the possibilities or the rationale behind the suggestion, and if it made a better book in English.

KM: In many ways, the process of working with a translator is similar to the process of working with an author—because a good translator has to do much of the work of an author, using language skill and creativity and artistry to make the text of a book work as fluidly in English as it does in the original language. Translators need to have great command of the languages they work in, but they also need to be skilled writers and storytellers. It’s rare for a person to be able to combine all of those skills, and it makes me glad that the industry seems to be swinging around more and more to recognizing the work of translators and the value of translated titles in general.

Lawrence is fabulous to work with because in addition to possessing all of the above talent, he’s also just a seemingly never-ending source of great ideas and enthusiasm. I’m grateful for all the times he’s passed projects along because they might be a fit, for all the great editorial suggestions he’s made, and for all the work he does helping to promote these books once they’re out in the world.

And, at the same time—Lawrence is spot on about this—he approaches it all without letting any ego get in the way. Editing and translation are both funny professions that way: you want your work to be invisible, in a sense. If someone is thinking about the editor, or the translator, in the middle of reading a book, it often means that something’s gone wrong. We’re both in the business of serving the story and the reader’s experience. In our work together, translator and editor, there is so much back-and-forth, give and take. It’s a conversation and a partnership that results in storytelling that’s so much stronger for the collaboration that goes into it.

I simply cannot thank Kathleen and Lawrence enough for taking so much time to answer my questions here today. Thanks too to Amy Storey and the folks at Eerdmans for setting this up.

I’m going to leave you now with a book trailer for one of my favorites of the year. A little story about two kids, far far away from one another, and a book you have to physically flip over in order to get their full story:

Filed under: Interviews

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

2024 Books from Printz Winners

Exclusive: Vol. 2 of The Weirn Books Is Coming in October | News

Fighting Public School Book Bans with the Civil Rights Act

ADVERTISEMENT