Elf Dog LaRue: A Guest Post by M.T. Anderson

Today it is my very great pleasure to bring you a post from author M.T. Anderson himself. Consider this NSFW if you don’t care for openly weeping at your desk.

Generally, authors for kids do not treat kids’ pets kindly. We kill them. It’s awful. Doesn’t matter what the animal is. Dogs, horses, raccoons, spiders. They all die to teach some child an important lesson about life and death.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

It’s traumatizing. As a young reader, I learned to stay away from animal books because I loved animals too much. Why don’t the kids ever get sent to the glue factory instead to teach the animals an important lesson about life and death?

So I determined that if I ever wrote a pet book, no animals would die. (You listening, Patrick Ness?) Now I’ve written a pet book – happy ending, don’t worry, smiles and face licks all round – and I’ve been thinking a lot about why pet books are both a genre that’s often trivialized or dismissed, and a genre that may be some of the most important writing there is.

I wrote a dog book – Elf Dog & Owl Head – a fantasy about a boy trapped alone in Vermont during the pandemic with no real companion but a magical dog – because, during the pandemic, I was trapped alone in Vermont with no real companion but a magical dog. It was basically my own story, except for the owl-headed people.

For the first year and a half of her life, I’d hated that dog.

I didn’t want her when my partner got her. The dog been rescued from a kill shelter, sent north, and she broke my partner’s heart, lying there in the kennel curled up sweet and docile like a little fawn in the ferns. So Nicole brought the dog home and it turned out the dog had been sedated that morning because she was getting spayed, and she woke up later that afternoon and started to tear around in frantic, destructive joy, and did not stop to sleep for the next two years.

Here’s a photo of her in one of her more quiet, reflective moments.

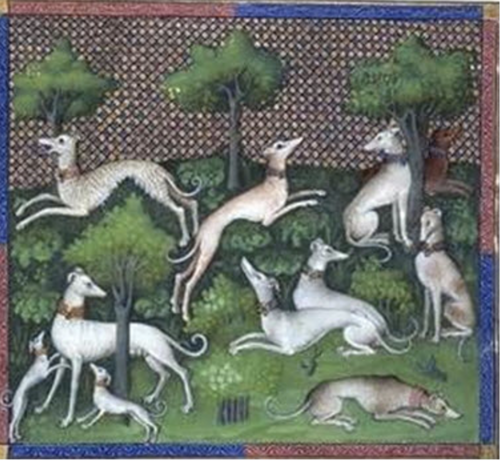

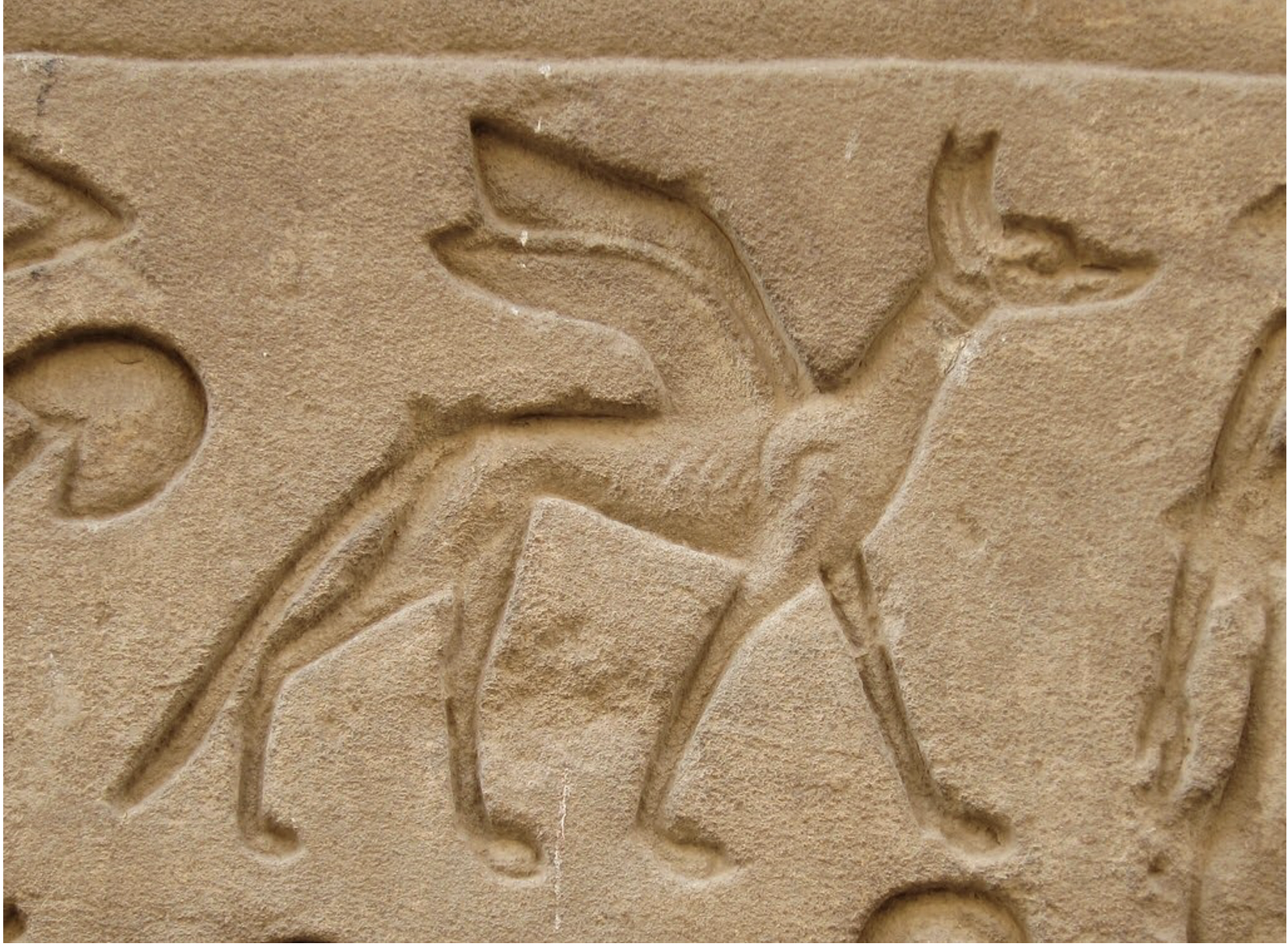

As she grew older and calmed down, I actually started to like her. We went on long walks through the hills. I started to think of her as a magical dog. She was odd looking, with giant ears, like a kind of vanilla Anubis, and she slept wound in impossible poses like a beast from some Celtic illumination in a long-forgotten book. When people asked me what breed she was, I would make something up – usually Scythian Lightning Hound – instead of giving the real answer: mutt. That’s something we all should do for ourselves, too.

Medieval dogs of the faerie hunt

An Egyptian elf-dog.

Everyone has stories like this about the animals that live with them. These stories are an important part of who we are. There are many families (sometimes without kids, sometimes with kids) where the pets are invested with the kind of emotional importance we usually reserve for humans. And animals rise to the occasion: as many of you will loudly agree, their emotional world is as big as ours. Their love – and yes, I even mean cats – is as deep as ours, and often much more pure.

Some years later, my partner left and the dog stayed. We both agreed she needed the forests. She was too wild for a city. So she and I lived together for several years in a little, haunted 18th century cottage on a dirt road off a dirt road in the mountains of Vermont.

A few months before the pandemic began in 2020, I was told she was going to die. She had a fully vasculated tumor around her aorta, and the vet said it was a miracle she was still walking around at all. He told me she had only a few days to live. You should set up a euthanasia appointment by Friday.

I prepared myself for her death. Still, each day I took her on a walk. She was weak. Her body was eating itself. But we walked through the hills as we’d become accustomed to, and as it happened, each day the walk was a little longer. On the fourth day, she chased a deer.

She just didn’t die. We walked and we walked. We walked on the dirt roads of town because the vet said her aorta would likely collapse with exercise and I would have to carry her corpse. I decided she would want to die running. So we explored, and each day we found new places on the back roads of town, new miraculous sights – cranberry bogs as red as the sunset, a barn built over the road – and finally we were walking five or six miles a day again, and she was gaining weight. There were a lot of tough nights, but gradually, for no very good reason, she was alive, and the tumor had stopped growing. The vet was astonished. She was fine.

And it was at that point that the pandemic hit. The walls rose up around all of us, all over the globe. But I was not alone. It was like I’d had a miraculous dispensation, the dog allowed to live so she and I could be together in this time of isolation.

So I started to write a book, full of thanks and the joy of companionship, about a boy in the Vermont hills and a miraculous dog he finds during the pandemic. She has escaped from a mysterious Kingdom Under the Mountain – believe it or not, I didn’t pick up on that symbolism for a while – and she shows the boy how to travel between worlds, and together they discover the secrets of the forests around them.

Every day, I’d go on a walk with the dog through the mountains for five or six miles, and I’d come up with that day’s plot, and then I’d go home to write in the afternoon.

And I really was aware that she showed me things I could not have found myself. She was responding to the unseen. She tramped along, twenty feet ahead of me, patrolling. She described great arcs through the woods around me. I could tell when bears or coyotes were close, because she’d drop back and stay by my side. (Yes, we met a bear one day. We didn’t talk long. I called out, “Howdy!” in my heartiest voice and he looked pissed and ambled off. If I learned one thing from my dog’s early years, it’s that friendly enthusiasm is far more off-putting than aggression.)

Ghostly explorations during a midnight snowstorm, 2020.

Pandemic photo: Author, dog, gin.

With an animal who knows us well, we develop a language that’s deeper than speech. They know our gestures, the way we breathe, the shift of our eyes, and we begin to read theirs too. This is not something trivial and cute. This is a form of communication that humans – and other hominids – shared long before we could speak. This is a fundamental level of engagement that precedes human society. The connection between humans and animals is one of the most profound connections there can be. Don’t underestimate the love of a pet and a child: they’re falling into a pattern older than cities, older than farms, older than talk.

On Midsummer’s Day, 2020, I finished the book. I wanted the timeline within the novel to be the same as the time of its writing: May 2020 to Midsummer, when the gates of the Otherworld supposedly all open and miracles can happen.

People like to talk about how writing is hard. Usually it is. In this case, though, it was a total pleasure. I have never had such an easy time writing a book – and oddly, despite that, I think it was one of the best and purest things I’ve ever written. My editor Liz Bicknell noted, “It’s the first book of yours that’s entirely devoid of irony.” It’s just filled with pure love.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Of course, eventually miracles must end, and so did LaRue. In summer 2021, a year after I finished writing the book, I wrapped up correcting the galleys and finally inscribed the dedication: “To LaRue, who escaped from the Kingdom Under the Mountain.” I emailed the galleys back to Candlewick and went for a walk with the dog. I could not know that exactly one week later, pretty much to the minute, I would be holding her body at the vet’s. She ran out of miracles, and, at age nine, she died.

I have had dogs die before, and cats, and frankly, human friends and relatives, and plenty of times, I’ve felt sorrow. But I don’t think I’ve ever felt grief before. This time I did: something disordered and sickening, like panic that grinds on and doesn’t let up. And so, having taught me what it’s like to be an animal, LaRue taught me what it meant to be human.

In the wake of her surprise collapse, I didn’t change anything in the book. I wanted it still to be a hymn of joy for that extra time, that miraculous reprieve. I wanted it to speak to kids with animals they love – and to kids who don’t have pets, but who want to feel what that love might be like. Yes, things die – the horses, dogs, cats, raccoons, spiders – but it is worth it to love them anyway, if only to be part of a tradition more ancient than humankind itself. It is worth it to know the grace of affection, and to glimpse the invisible world all around us. It is worth it, so that we know we have lived on this Earth, and see what it has offered us since before we first rose from our stoop and became the tangled and anguished things we are.

New York Times bestselling author M. T. Anderson is the author of Feed and Assassination of Brangwain Spurge (both Finalists for the National Book Award), The Pox Party (winner of the National Book Award), adventure series, and books about music such as Symphony for the City of the Dead: Dmitri Shostakovich and the Siege of Leningrad. His most recent book is Elf Dog & Owl Head. To hear more about his thoughts on dogs, check out this episode of Rumble Strip.

Author Steve Sheinkin took this photo demonstrating LaRue’s powers of levitation.

The last photo of us together, a few days before her death.

Filed under: Guest Posts

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Name That LEGO Book Cover! (#53)

Exclusive: Vol. 2 of The Weirn Books Is Coming in October | News

Fighting Public School Book Bans with the Civil Rights Act

Take Five: Middle Grade Anthologies and Short Story Collections

ADVERTISEMENT

I like to think I’m rather experienced as a devourer of children’s literature for more than a half a century. Of course, the name M.T. Anderson has come to my awareness many times. However, it is only today that I have come face to face with this man’s words. I confess have never read one word of his publications.

Betsy, providing space for this literally AWESOME post I feel extremely attracted to his writing here as a fellow dog lover. I MUST purchase and explore Elf Dog and Owl Head. Should I not personally love the book I have a special small rural Maine library that benefits from my donations. As always . . . thanks so much for setting me up for a blind date with Mr. Anderson! My nine year old certified therapy Golden Retriever (aka “best friend) and I love you both!

P.S. If I recall correctly, Betsy, you are actually NOT totally smitten with canines. Correct me if I’m wrong about that.

What a beautiful essay. I am sorry for you grief, M.T., but I am so very glad that you had LaRue in your life. Anyone who doesn’t think a dog can feel “real” emotions like love, has sadly never had that bond that some of us have been lucky enough to experience.

Thank you both for this! I always cry easily, and this just made me smile!

I didn’t think I could love Tobin more…. How wrong I was.

So nice to read this – and I also love the photos! The midnight snowstorm really reminds of Edward Gorey and some of the dog drawings he did.