Bologna Discussion: “This is an effort to push kids back in the closet and they don’t care if they kill themselves there.” Censorship and Book Banning Around the World

This year at the Bologna Children’s Book Fair I identified three major themes that came up many times in the course of the schedule and program:

- Ukrainian children’s literature

- AI and how it may affect children’s illustration

- Censorship

To the latter topic, I was able to attend a very interesting panel entitled “Censorship of Books: what is the state of children’s book banning around the world and what is being done?” The topic itself is interesting, but I was particularly intrigued because if you were to ask me how book banning and censorship works in other countries I could provide you only the barest of outlines. I was even more intrigued by this panel when I saw who was speaking on it. To wit:

- Barbara Marcus (President and Publisher Random House Children’s Books, USA)

- Jon Anderson (President and Publisher of Simon and Schuster Children’s Publishing and Board Member of the National Coalition Against Censorship, USA)

- Dora Batalim SottoMayor (Pedagogical Coordinator and lecturer on the Postgraduate Course in Children’s Books at the Università Cattolica in Lisbon and lecturer at the Maria Ulrich School for Childhood Educators, Portugal).

- Doris Breitmoser (Managing Editor of the Association for Children’s Literature/Arbeitskreis für Jugendliteratur, Germany)

- Giorgia Grilli, (Professor of Children’s Literature at the University of Bologna and co-founder of the Centre for Research in Children’s Literature at the Department of Educational Sciences, University of Bologna, Italy)

- David Levithan (who was bafflingly listed only as “author, USA” but was speaking on behalf of Scholastic too)

So, put another way, three American children’s book publishers (two of whom are the actual friggin’ presidents of two of the “Big Five” companies), a rep for Portugal, a rep for Germany, a Professor from Italy and an author (who is also one of those publishers).

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

This was going to be interesting.

It started off fairly standard, of course. After finding the room (they didn’t make it easy, which may have accounted for my good seat) Barbara kicked us off. Technically she was the moderator (a job that proved to be slightly more challenging than I think she might have initially envisioned) but she kicked us off with some context. Here in America I think we’ve heard the statistics on the state of censorship and book banning fairly often, but it was probably new to some of the attendees. To kicks us off she recommended a study into the state of censorship in the U.S. put out by PEN America called the Banned in the U.S.A. Report then read a selection from it to “set the stage”. According to the report, there were 2500 registered book bans that PEN knew of in the last year and those affected 2K titles, almost 1300 authors, 260 illustrators, and some smaller number of translators. The kinds of books – 41% explicitly address LGBTQIA themes. 30% – people of color. 21% issues of race and racism. 22% sexual content of varying kinds. 50 groups are involved in pushing for book bans. 8 have local/original chapters that number at least 300 in total. Some operate predominantly through social media. Most of the books are YA books (this was news to me). Of the bans 96% were enacted without following the practices for book challenges.

Having set the stage she handed the mic over to Jon Anderson who has been an active member of the National Coalition Against Censorship (NCAC) for more than a decade. Jon hit all the usual points to give a sense of the USA today. He noted that censorship in the States has never been worse. That in the past such bans were “unorganized and sporadic”. But in the last few years things have exploded. He placed much of the blame on right wing politicians as part of a cynical attempt to stoke their base for political support. As a result the NCAC is working to marshal students themselves, teaching them how to fight back for their rights. To fight organized censorship you must organize the people who are on the receiving end of that censorship. And as a beacon of light, the students ARE fighting back for their rights.

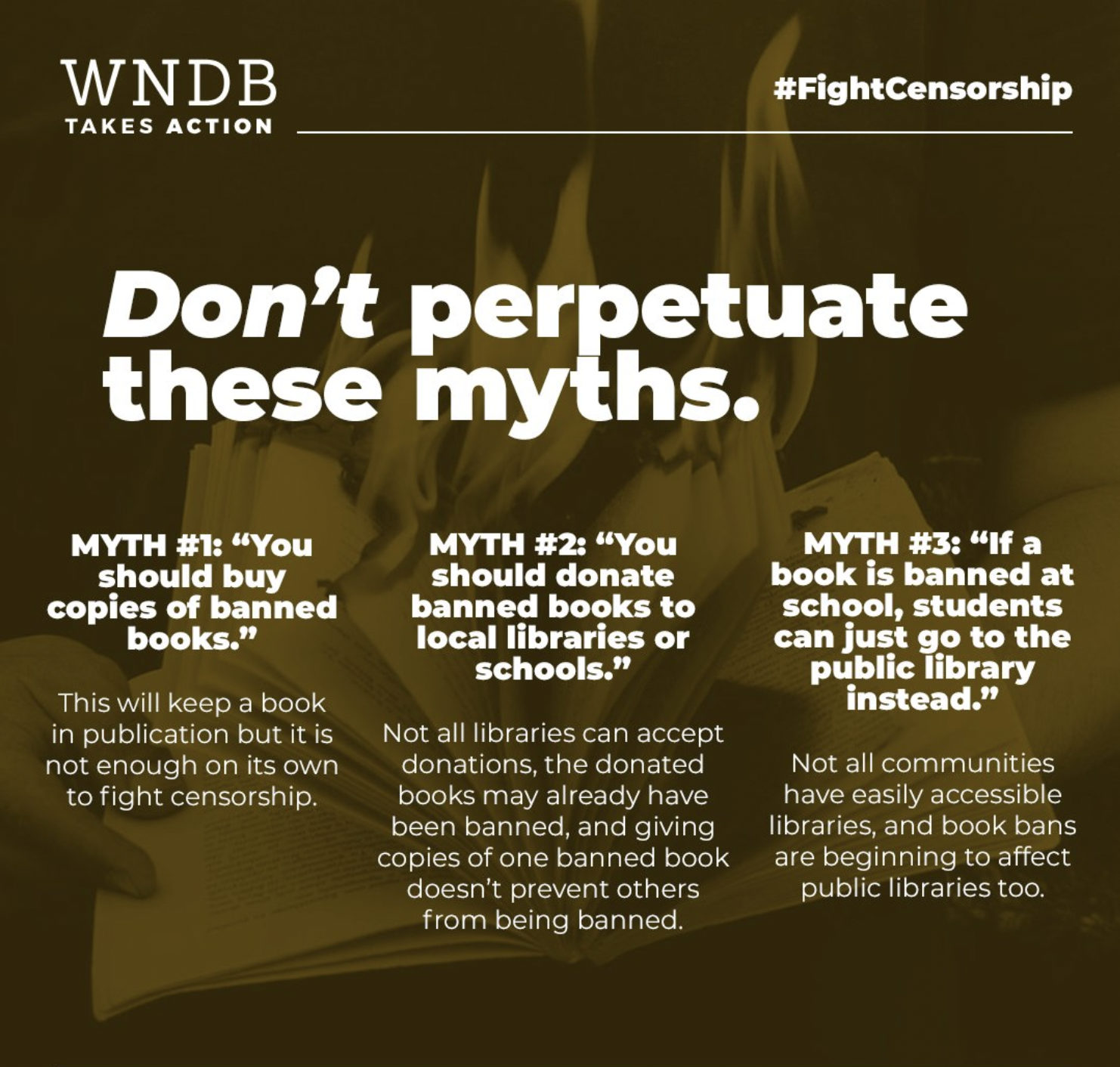

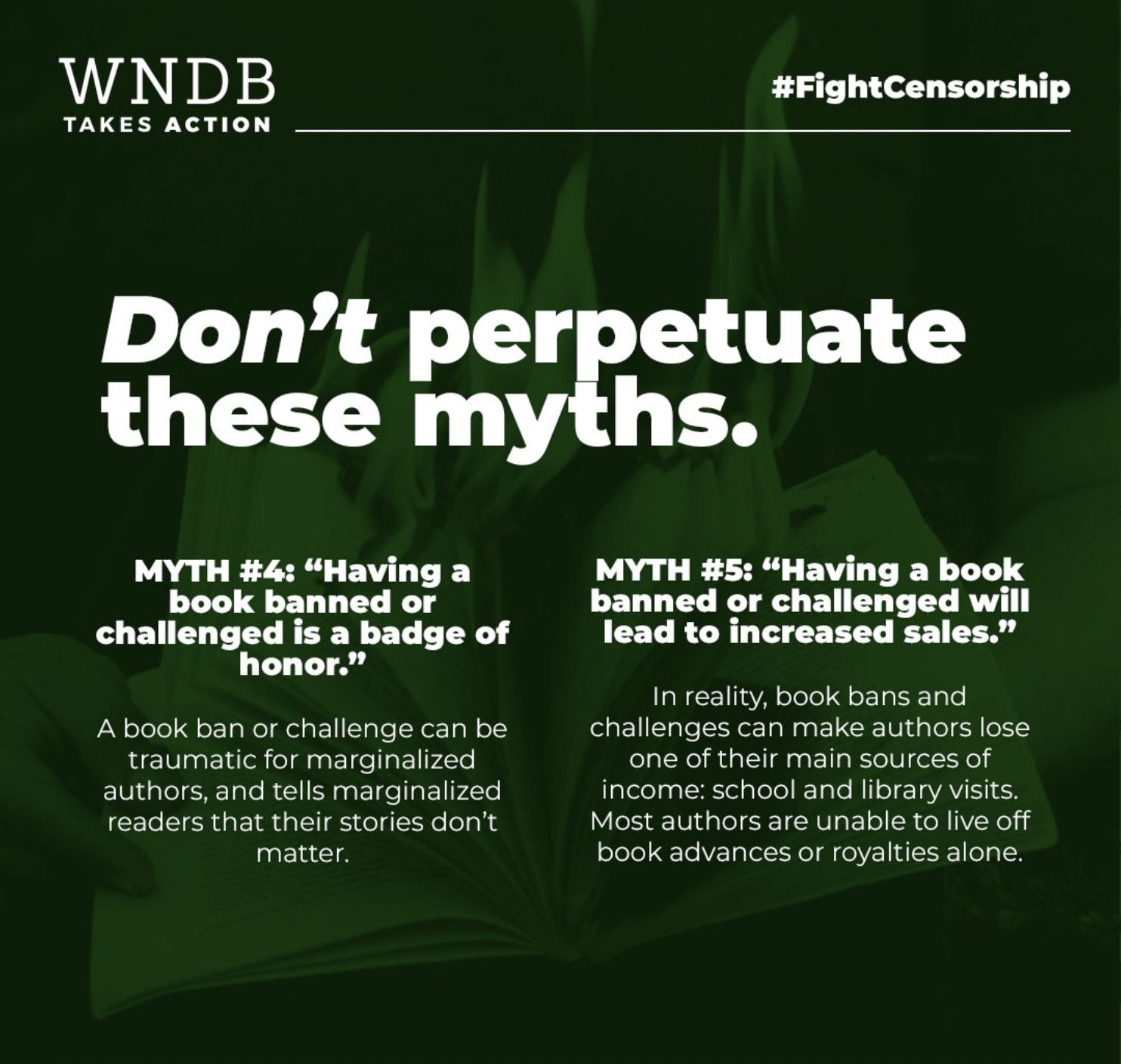

All told it was fine, but I was surprised to see Jon commit a bit of an interesting blunder that folks have been fighting against lately. You may have seen the recent release of the We Need Diverse Books list of the five myths of book bans.

Jon was by no means alone, but he kept leaning into Myth #5. It’s entirely possible that sales of And Tango Makes Three did skyrocket after its last ban, but leaning into that fact so heavily made me uncomfortable. It distracted from what was otherwise a strong talk.

The way the discussion was set up, each person got a set amount of time to speak. All well and good if you monitor your time. Alas, some folks had some difficulty with that. Interestingly the Americans bookended the Europeans in this talk. What that meant was that you got a crystal clear vision of American book banning at the start and at the beginning, but of course in Europe the focus can be very different. I’m not sure how it could have been arranged differently, though. However you look at it, Dora Batalim SottoMayor spoke next and she had a very different take on the entire affair. Since Portugal, it appears, does not have organized book bans in the same way as the States, she chose instead to lean into the idea of censorship itself, starting with “We are all censors in some way.”

In the beginning, Dora leaned into examples less of censorship and more of equity. For example, she mentioned that twenty years ago in Portugal children’s books would not list the name of the illustrator on their cover. Nor, for that matter, would the illustrator make as much as the author. Now both author and illustrator may appear on a book cover together. That’s good, but apparently these changes don’t apply to textbooks, which many illustrators also work on.

Glancing mention was made of the fact that when European illustrators do a job for the US they’re handed “four pages of what they can’t do.” Probably true, honestly.

At this point Dora started discussing her problem with the “excessive sensitivity” these days when it comes to inclusive language. To her mind, inclusive language was clearly on the same level as censorship, going so far as to say that it’s coming from the outside and “invading Portugal”. As one example she said that if a kid who was gay, short, and had pimples chooses a book about a kid who is gay, short, and has pimples, that completely limits them. Never mind that they may never have encountered a book about a child like themself before. The panel was not set up as a discussion, so no one challenged any of these assertions at any time (though, as you will see, David Levithan may later have implicitly challenged them without being explicit).

Dora then turned the conversation back to the matter at hand. Her focus zeroed in on governmental censorship. Bringing up two cases of such censorship with the same book, she discussed War by By Jose Jorge Letria, illustrated by André Letria. One case involved an international book award and the Chinese judges that made the book disappear. I was a bit unclear on what award this might have been. The other case with this book, and more recent, was that in the week before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, a Russian publisher bought the book. They moved quickly, in the hopes of distributing it, but the government caught wind of the notion and prevented the book from leaving the warehouse.

On the topic of implicit self-censorship, Dora zeroed in on booksellers. She said that ten years ago, the prevailing attitudes surrounding books with Black characters were that the books were considered to be “of no interest”. Only when the schools made them popular did they start to sell. But such attitudes continue to be difficult to break down. One bookseller was quoted as saying that, “we don’t make books about gypsies because gypsies don’t buy books.” I can count five things wrong with that statement already.

Doris Breitmoser spoke next, pointing out that out that “censorship” for Portugal and Germany, is perhaps not the right term. Now as this fair shows, children’s literature is very diverse. However, kids books are subject to “special framework conditions”. Her term is “discourse norming”. A rather fascinating term, it seemed to mean that children’s literature must be measured against the prevailing ideas of childhood and what is appropriate for one age group or another.

Doris had a fair amount of experience with IBBY (The International Board on Books for Young People) and noted that in some cases, when a book from one country is published in another, sometimes it may have to go through censorship authorities, as in places like Iran.

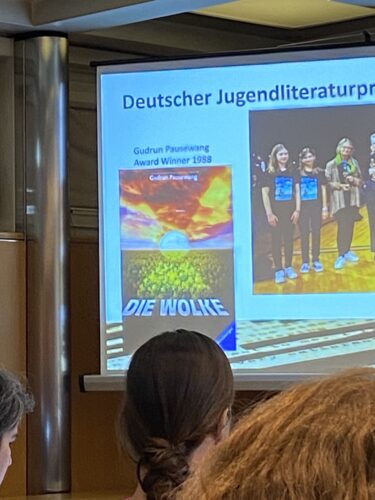

On the topic of awards, Doris mentioned that there was a case of this in Germany. In 1988 the novel Die Wolke was about what she called “atomic superhazards” (we’re just gonna assume she meant atomic power though I am now officially naming my next band Atomic Superhazard). The point of the end of the book is to show how this can disrupt lives. Needless to say, the government of the time didn’t like it. Politicians intervened saying that the award committee could not award the book or author.

Talking about children’s book classics, the recent case of the text of a Roald Dahl book getting changed is not a singular case. She said that certainly outdated language has a tendency to be changed. To illustrate this she brought up two books from the 50s and 60s. One was by Michael Ende in 1960 called Jim Knopf und Lukas der Lokomotivführer. The plot, and this is apparently the actual plot, is that a Black kid is adopted by the engine driver of a train. What was changed? I’m just gonna direct you to the Wikipedia page and you can draw some logical conclusions. Another book mentioned was Die Kleine Hexe by Otfried Preußler. In that one there are references to kids dressed up like “Indians and Eskimos”. Doris wasn’t outright calling the changes censorship, saying that there isn’t an answer. After all, there are some who think a children’s book is a “work of art” and that no interference with the text is acceptable. But she sees how not changing the text could be problematic for teachers or parents. She did not mention how it was probably far more problematic for students. In any case, she suggested instead adding maybe a prefix or epilogue or footnote could be an option because just changing terms is “starting a huge mess” and she sees it as a slippery slope. This reminded me of the changes made years ago to Doctor Doolittle by the McKissacks. They did include the Introduction about the changes but they also made the changes. It’s not really an either/or type of situation.

But, to be frank, this also reminded me of something wise Kyle Lukoff once said. Apparently he was twisting himself into circles trying to find reasons to justify how you could change an old book with outdated mores to contemporary attitudes when a student just said to him, “Kyle, sometimes you just have to let it go.” Wise words, that.

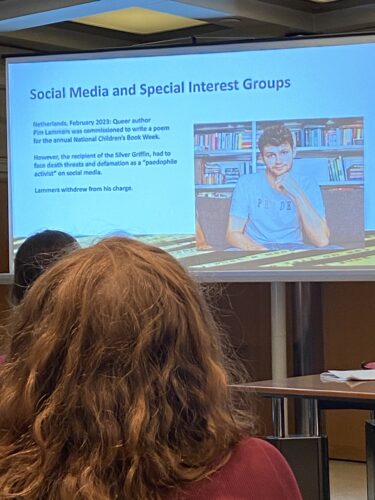

Many of the discussions this day were about older books but Doris also ended with a startling case that sounded like it was ripped out of the American right wing’s playbook. As recently as February 2023 a queer author by the name of Pim Lammers was commissioned to write a poem for the National Children’s Book Week in the Netherlands. But when this was announced the man faced death threats and defamation as a “paedophile activist” and felt he was forced to withdraw. To be honest, I had no idea that this was happening anywhere outside of the States.

I was feeling a bit odd about some of the statements made by the previous two guests. Conflating censorship with attempts to right historic wrongs feels like a false equivalency to me. But when Giorgia started speaking everyone knew right off the bat that this woman knew what she was talking about.

She started off by saying that the situation in Italy right now makes her think of an article in the Washington Post she once saw that said that every year in the U.S. 1000 titles are banned from schools. That’s a huge number. In Italy they do not have as many banned books. Why? Because they have a deeper problem. “We don’t ban books in schools because we don’t have books in schools!”

Quoting liberally from scholars, Giorgia told us that novels for kids have never made it into their classrooms because, historically, the novel was considered subversive in and of itself. Novels make us become critical of society as it is. And novels can even make us critical of what we’re taught in formal education. Old-fashioned thinking? In Italy the situation has never been rectified. So for her, the true battle in Italy is to finally make it normal for each school to have books that are not textbooks. And to have librarians (which they don’t have) and school libraries.

To be frank, I found all of this fascinating, just as I found Giorgia’s understanding of the censorship of absence invigorating. The presence of the school library in Italy is an exception rather than a rule. And a good well stocked library is utopian. In those rare times when you actually encounter one it’ll usually be full of books that were left behind by a teacher or a well meaning parent. Such books were never selected by experts and they’re certainly never up to date. To her mind, this is worse than banned books because you don’t even offer books in the first place! These schools simply don’t consider them an essential part of school life.

How can this situation change? You would have to have some cultural association or a dedicated teacher to provide books. But, there can be consequences to that. Giorgia proceeded them to recount for us a story that sounded like it was straight out of the Ron DeSantis playbook. The one big example of books being banned in Italy was linked to one of these projects alluded to earlier. In 2015 in the Venice area, a group of librarians and psychologists, supported by the local left-wing government, made a list of picture books that all the public schools would receive as a gift. These were books aimed at kids between the ages of 0-6 years old and were selected for tolerance and inclusiveness. Some of them dealt with different kinds of families. You can see where this is going. Yes indeed, there were gay parents in some of these books, often nonhuman representations. The trouble? An election. Suddenly these books were a political issue. And sure enough, the new conservative mayor removed ALL of the books from the schools just as he’d campaigned. Not just the ones with the gay parents but all of them, like Leo Lionni’s Little Blue and Little Yellow (which I don’t think even happened in the States at the height of the Southern blowback against integrated families).

For Giorgia, one of the great dangers coming out of cases like this is self-censorship. Which is to say, people may try to avoid working on anything controversial. “What worries me is a world where artists adapt to the dominant view.” It made me wonder if we’re seeing any of this in the States. She says art should always be disturbing more than reassuring. Art should always make us see things that aren’t there but that we would never detect without its words and images. After all, a child is a wild thing and not a tame creature. A child does not belong entirely to us. We need that kind of representation of children in children’s books. And in spite of Maurice Sendak, and in spite of all the other examples from other authors, representing children as complicated creatures with inner turmoil and a wide range of emotions doesn’t happen as often as it should. Instead, you’ll see this tendency is to portray children as smiling, happy cheerful little persons.

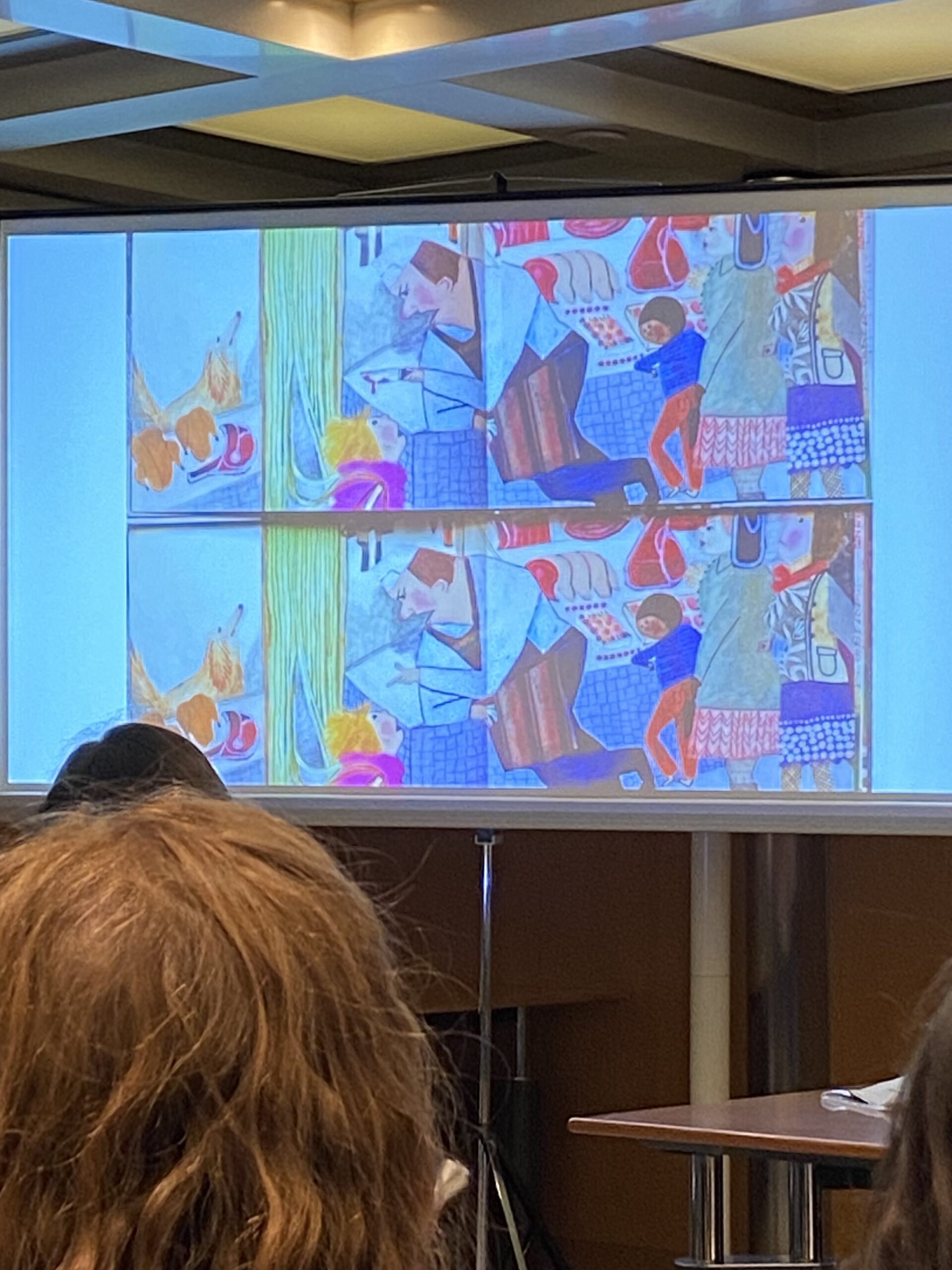

To illustrate the point of childhood being dumbed down, she brought up the book The Wonderful Fluffy Little Squishy by Beatrice Alemagna. Apparently, in the original edition there is a scene where the girl is at a butcher’s and the man is speaking to her while his knife drips blood. Yet when Thames & Hudson published the book they erased the knife and Beatrice had to redraw the hand. This makes no sense to Giorgia. “Children are obsessed with blood!” Such changes disturb her. As she said, at least when a book is banned it exists. Ultimately she worries about a world where books that are disturbing to someone don’t exist. Because that would be the end of art.

And speaking of art, we turn at last to our last speaker. David Levithan found himself in the unenviable position of speaking last on a panel that, as you can see, was covering quite a wide range of topics. Happily, he chose to stand up as he gave his presentation. The panelists were not on a raised stage, so for those of us sitting, we couldn’t really make him out clearly until he did that.

Now we were turning our sights back to the United States. David asked where you might find a law passed to forbid gay content in books in schools. The answer? Both Putin’s Russia and Florida. But David wasn’t going to rehash the material already covered. Instead, he made it clear that though he was just in the North Texas Teen Book Festival he still took the time to come to Bologna. Why? To sound the alarm. The conservatives of Europe are looking at America at this movement of book banning. They’re seeing that this is an efficient way to roll back civil rights so, right now, they’re dusting off the censorship playbook. This is not an American problem. It can happen anywhere (as Giorgiana showed with her discussion of Venice and Doris with the recent case in the Netherlands) and what we need to do is to fight.

“The books don’t matter. The kids matter.” And these books are being banned to scare kids and adults. “This is an effort to push kids back in the closet and they don’t care if they kill themselves there.” If the statistics Barbara quoted earlier are chilling then we have to take action.

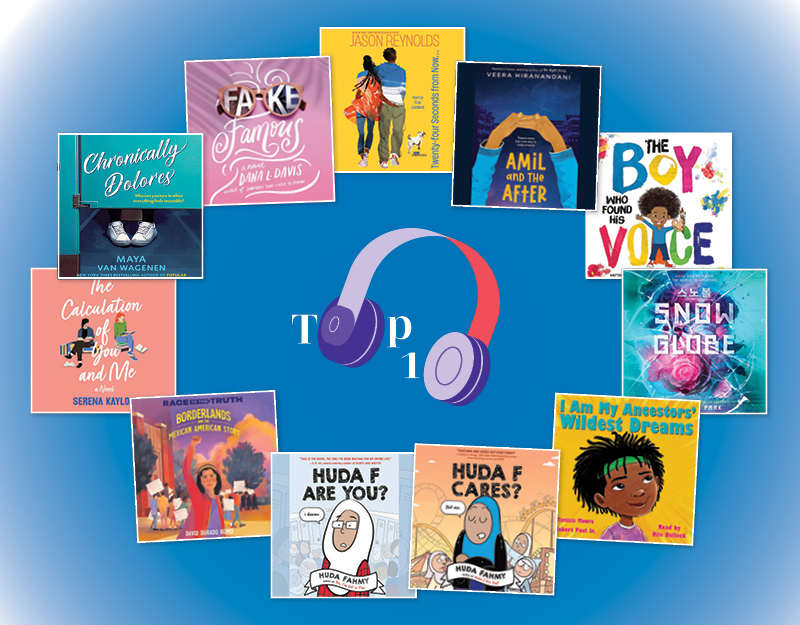

Now there are a lot of ways you can look at all of this. Certainly, you can look at this as devastating. But you can also see a positive aspect to this because honestly it means we’ve published over 3000 books that these people are attacking. That’s 1800 authors. When David wrote Boy Meets Boy he was immediately cancelled/protested/you name it. Now, after 20 years, more authors are writing other LGBTQIA+ books and getting published. Remember, it wasn’t long ago that foreign publishers would tell Americans that they weren’t ready for queer literature. Just walk around the fair now and see how that’s changed! The problem is that now politicians and the far right are trying to end that progress. But as David said, “1,800 of us writing these books. That means that publishing is actually doing the right thing. We are supporting the voices that need to be heard and scaring the people trying to shut us up.”

David says he often says to people, “I bet you didn’t become a teacher/ librarian to keep books out of the hands of children.” And no one went into publishing not to publish the books the kids need. So his trip to Bologna was, as he said, meant to raise the alarm that people need to keep fighting.

Now here’s my favorite part of the speech: “Keep publishing and pushing these books. I don’t give a shit about Roald Dahl using the word ‘fat’ or ‘enormous’. THAT conversation is a distraction. We have to focus on the things that are most important to the kids and make sure the media is paying attention to that.” He pointed out that when it came to the Roald Dahl changes, in light of the book banning (which is real and happening now) that brouhaha was basically a theoretical conversation.

Like a friggin’ breath of fresh air, he was. The times are dark. Things are difficult. But where we chose to focus is important. So yes, feel free to hem and haw over whether or not the changes to The Witches was imperative or not. Meanwhile there are librarians literally facing imprisonment over making books available to kids.

Now you tell me. What will you chose to find more important?

Filed under: Bologna Children's Book Fair

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Our 2025 Preview Episode of The Yarn Podcast!

Mini Marvels: Hulk Smash | Review

When Book Bans are a Form of Discrimination, What is the Path to Justice?

Take Five: Gun Violence in Middle Grade Fiction

Our 2025 Preview Episode!

ADVERTISEMENT

Hey, thank you for this very great article.

It’s super interesting to read and to be made aware of the book bans and censorship from different countries. Like you, I don’t know much about these things in other countries than my own (and here I think I might not know enough), and it’s troubling to see the uptake in both.

There is one thing I stumbled over, though it’s not directly about the topic of the panel. It has been rubbing me a little the wrong way because I read and loved “Die Wolke” as a teenager and it left a deep impact on me. I think the content of the book might be important to the point Doris Breitmoser tried to make with it. The book is about a nuclear disaster (and super hazard might have been a too direct translation from the German word, a false friend, my teacher would call it) of an atomic power plant and the repercussions of that. It tells the story of a girl living near that power plant when the meltdown happens and her way out of the poisoned zone and to a part of her family in another part of Germany. It’s very heartbreaking at times because it doesn’t hold back either on the repercussions of radiation poisoning, or the dark and bright sides of humanity when everyone fights for their own life, or the expected misinformation about the truth in the affected area that is spread to the rest of the public. All things that probably many people didn’t want to be discussed a year after the Chernobyl disaster.

Thank you for the context! It’s not a book that, to the best of my knowledge, became well known in the States. I appreciate you chiming in!