Twin Stars, One Light: A Fire of Stars Dual Interview with Kirsten Larson and Katherine Roy

Buzz. How the heck do you build buzz when you have a new book out?

Your publisher will do a bit of work on their end, but the bigger they are the less time they’ll have for you individually. You can personally send your book to all the book award and state committees you can name. You can go on blog tours. You can haunt the local bookstore and plead for a signing. Maybe even hit up the local radio station. You can go on podcasts. Talk to newspaper reporters. There are as many different ways to promote a book as there are stars in the sky.

… stars in the sky . . . well now, that reminds of something too. What if you’re book is a work of nonfiction? How do you promote that exactly? One method, and this is tricky but I recommend it, is to write a really really good book. Seriously, the kind of book that gets starred reviews from major review sources. Maybe you could get a Kirkus starred review, and a School Library Journal starred review, and a Publishers Weekly starred review , and a Shelf Awareness starred review for starters. Maybe it could be Junior Library Guild selection to boot. And maybe, just maybe, if you manage to do all those things . . . maybe you could let me interview you as well.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Today on the blog we’ve the creators of the multi-starred, remarkably written, and beautifully illustrated The Fire of Stars by Kirsten W. Larson, illustrated by Katherine Roy. Here’s how the publisher describes it:

“Wrapped in a blanket of sparkling space, an unformed star waits for its bright future to begin.

Deep inside, something glimmers and glows: a new light.

Astronomer and astrophysicist Cecilia Payne was the first person to discover what burns at the heart of stars.

But she didn’t start out as the ground-breaking scientist she would eventually become. She started out as a girl burning with curiosity, chasing the thrilling lightning bolt of discovery, hoping one day to unlock the mysteries of the universe.

With lyrical, evocative text by Kirsten W. Larson and extraordinary illustrations by award-winning illustrator Katherine Roy, this moving biography powerfully parallels the kindling of Cecilia Payne’s own curiosity and her scientific career with the process of a star’s birth, from mere possibility in an expanse of space to an eventual breathtaking explosion of light.”

Given the chance to interview the women behind the title, I had lots of questions on hand:

Betsy Bird: Oh, this is a thrill. Thank you both, so much, for joining me here today. And after reading THE FIRE OF STARS I am just chock full of questions. Kirsten, let’s start with you and with the most obvious of them first. Now we’ve seen a whole plethora of picture book biographies about women who studied the stars in some capacity over the last few years. This is, however, the first time that I recall seeing a book about Cecilia Payne. How did you first learn of her? And why did you think she’d make a good subject for a bio for kids?

Kirsten Larson: I first learned about Cecilia Payne during an episode of Neil deGrasse Tyson’s COSMOS called “Sisters of the Sun.” It featured Cecilia Payne alongside other women who worked at Harvard College Observatory, including Annie Jump Cannon and Henrietta Leavitt, both of whom already had picture books (ANNIE JUMP CANNON, ASTRONOMER by Carole Gerber, illus. Christina Wald and LOOK UP! by Robert Burleigh, illus. Raul Colon. )

I was instantly drawn to Cecilia when I learned that many consider her dissertation, which she finished at age 25, one of the most brilliant ever written in astronomy. And then, when I learned Henry Norris Russell, arguably the most powerful astronomer of the day, told her her conclusions were flat out wrong despite her evidence. … Well, how could I not write about her? I love people and ideas that subvert expectations.

BB: Little wonder then that your illustrator became Katherine Roy then. She’s always subverting expectations, left and right. And Katherine! A delight speaking to you as well! If anyone knows anything about Katherine Roy it’s that she knows how to render science on the page. And this book? Chock full of the stuff. How did you come to be involved in the project? And what did you think of the manuscript when you first read it?

Katherine Roy: Betsy! I’m so delighted to speak to you, too. And—why thank you! I do love me a good science rendering! 🙂 How did I become involved in the project? Well, Melissa Manlove—our editor on The Fire of Stars at Chronicle Books—was basically the first children’s book editor I ever met in publishing, years and years before my eyes twinkled about great white sharks. And ever since Neighborhood Sharks first came out (and BTW Melissa does an incredible imitation of a shark, ask her to do it sometime), she and I had been trying to find the right manuscript to work on together. After two or three others that weren’t quite the right fit, she sent along Kirsten’s manuscript through my agent, and I liked it right away. It was simple but incredibly elegant, with this brilliant tension between the two star stories at once. I said yes almost right away. I remember my one concern at the time was that the only reason I had passed physics in high school was because I’d made the visual aids for group presentations, but my agent, Stephen Barr, assured me that fluency in astrophysics wasn’t a prerequisite for illustrating the book, and—thankfully—he was right. He usually is.

BB: You may not have had a degree in astrophysics, Katherine, but your co-creator here has a fair amount of science under her belt. Kirsten, as a former employee of NASA, one would think that all your books for kids would involve space in some way, but as far as I can tell this is your first foray into that particular science. Was this a topic you’d hoped to do for a while or was it something that required just the right subject matter?

KL: THE FIRE OF STARS was the second picture book my agent Lara Perkins (Andrea Brown Literary Agency) and I sold, though it will be my third published picture book. We all know how publishing and its timelines work. Ha ha!

Speaking more broadly, I’ll just say that I’m interested in a lot of different things, from STEM to history and art, and I’m committed to following my curiosity. When I’m picking biography subjects, personalities tend to matter to me more than the field the person is working in. I also think hard about the takeaway for young readers and how the subject might fit into the curriculum, especially for STEM topics. And if I have an excuse to write about airplanes or astronomy, and encourage kids to pursue their passion for STEM, even better!

BB: Speaking of science, Katherine, you’ve done such a nice variety of science related books for kids. This isn’t the first biography you’ve done per se, but it is a little different from ones you’ve worked on in the past. Was the mix of a dual narrative with science and a personal history part of the lure when you took the job on?

KR: I was very attracted to the possibility of making art that told two stories at once. I was also excited that there was a lot of fresh material to explore because at the outset I didn’t know anything about Cecilia Payne or how stars are formed. So the fact that there was room to stretch and play made me keenly interested in the project. Had I known how difficult it would be to actually create the visual structure for telling two stories at once, I might not have agreed to it, haha—because figuring out how to do the art for this book was HAAARRRRDDDDD (see Kirsten’s comments below). In the end, I think it was my MFA in Cartooning that saved me. Who could have predicted that fluency in comics would be so useful when signing up to illustrate a narrative historical nonfiction double read aloud on the simultaneous birth of two very different kinds of stars? *grins*

BB: The things they never bother to teach in art class, right? But let’s get into that HAAARRRRDDDDD structure the book is utilizing. Kirsten, right from the start you make the choice to parallel Cecilia’s life alongside the process by which stars are born. Aside from being just very cool, this breaks up the narrative from the standard format of picture book bios in an innovative and eclectic way. Was it always the plan to mirror the science alongside the biography or did it come to you later in the editorial process?

KL: This was an eleventh-hour decision, and just goes to show you that you never know when an idea is finally going to come together. In May 2017, my agent Lara and I were preparing to sub this book as a run-of-the-mill picture book biography. Meanwhile, I was working on a blog post featuring Hannah Holt’s query letter for THE DIAMOND AND THE BOY (2018). Her book was still months away from release. Hannah pitched her biography of Tracy Hall, who invented lab-produced diamonds, as “a two-tale picture book—a turn and flip. …The two stories meet in the middle with a shared phrase.”

Cecilia Payne talks about the thrill of discovery; well, this was the thrill of finally discovering my story! I decided to tell the story of star formation alongside Cecilia’s formation as a star scientist. And I aimed to have a shared line of text that applied to both stories at the same time on every page.

Of course, it was much harder to do than I expected. I tried to backtrack, but Lara kept encouraging me. She knew I could do it. But it was so, so hard. And then it made life hard for Katherine too!

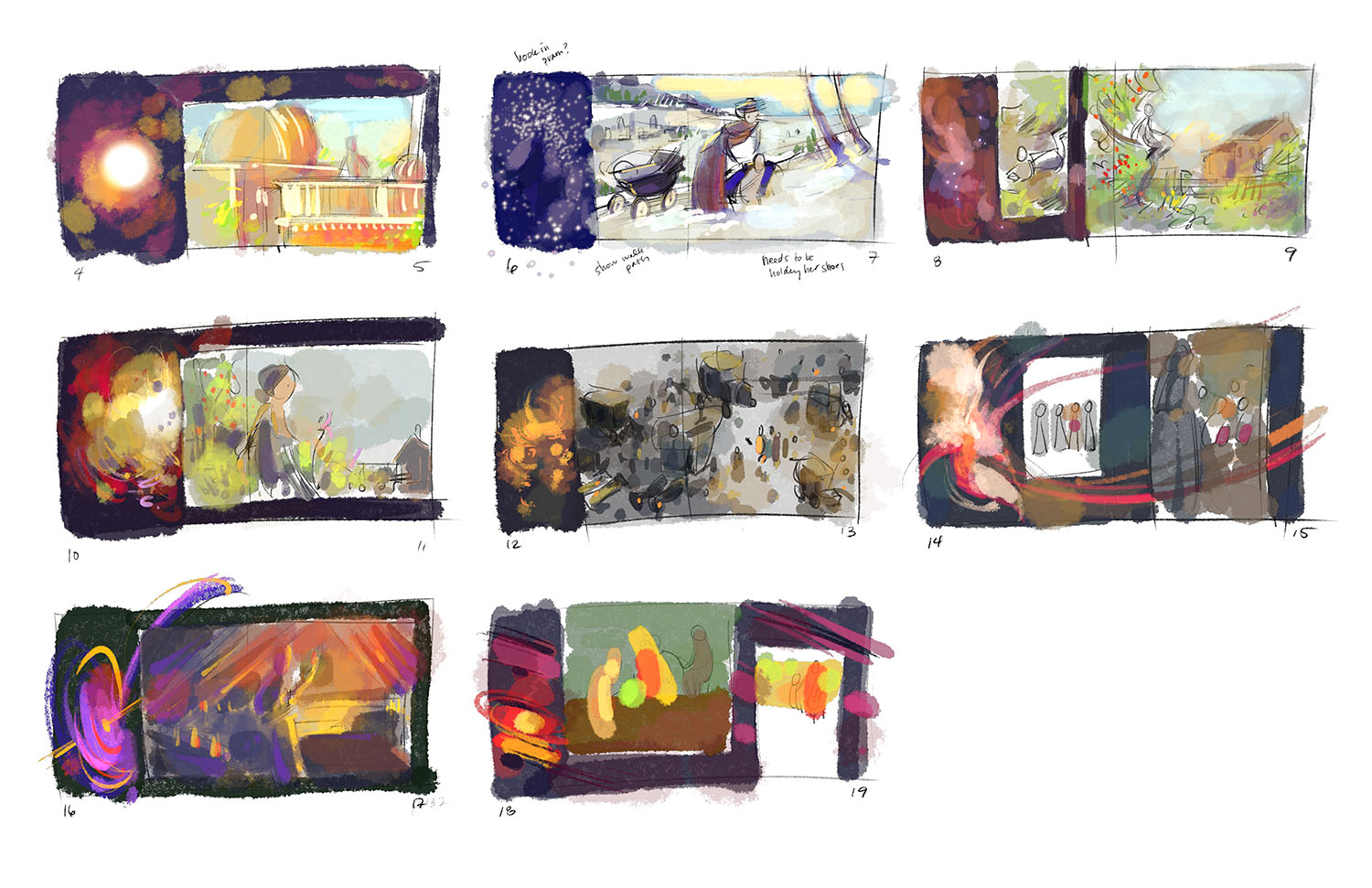

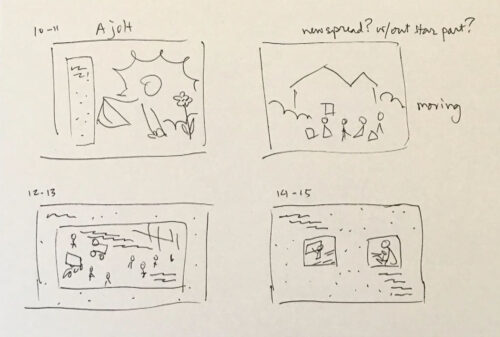

BB: Yeah, I want to lean into that a little more. Katherine, did you have a clear cut sense of how you wanted to lay out the design of these pages when you began? As it stands the birth of the star sequences start as half of a page at the start and then slowly spread out to appear behind the biographical sections. It foregrounds Cecilia’s story, but also makes it clear that the star sequence is closely tied to her life and work. Did you play around with different ways of showing this at the star?

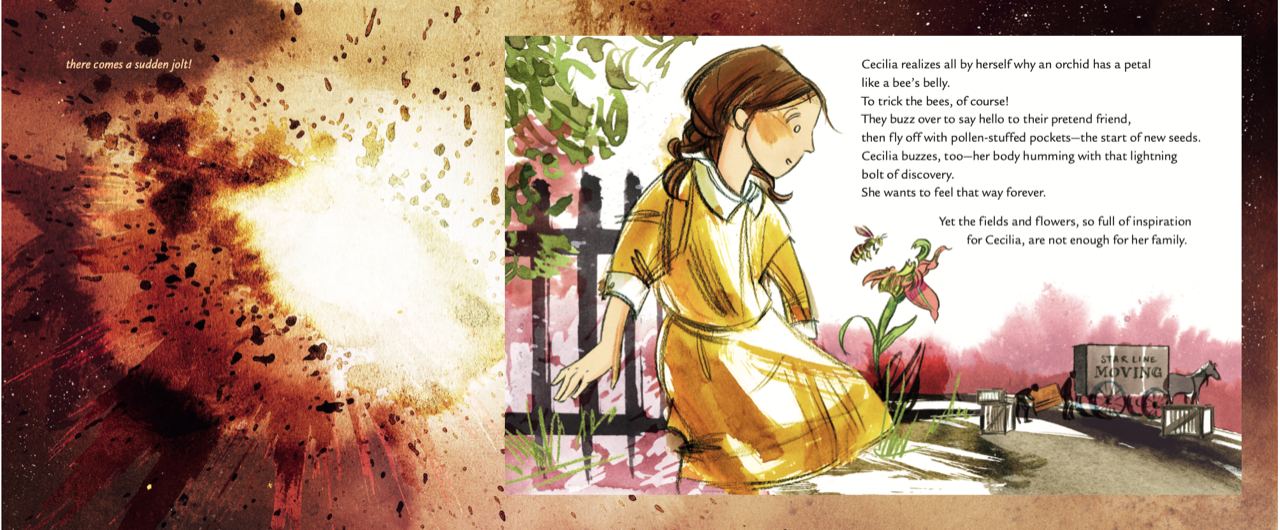

KR: Melissa Manlove and I discussed the page design in our very first exchange. At the time, we both entirely agreed that the book should have a “split screen” running horizontally across the spreads to tell the two stories at once—the star’s story on top and Cecilia’s story on the bottom. This approach sounded really useful at first, but I kept hitting wall after wall. It took me months to see that the “split screen” was making draft after draft feel crowded and flat, and not because the story was the problem, but because my page design wasn’t mirroring the tension in the manuscript.

Then—after months of flopping around—I discovered that Kirsten had used The Diamond and the Boy by Hannah Holt as a mentor text. I tracked that book down and saw that the illustrator, Jay Fleck, told the diamond’s story solely on the left and the boy’s story solely on the right. I immediately scrapped my “split screen” drafts and tried the same structure, reworking the entire book with a left/right split. I sent it to Melissa, but she still didn’t think the book was working—the star story had too much space and Cecilia’s felt too crowded. At which point, I sort of threw my hands up. I was completely out of ideas. Maybe I should quit.

Trying to coach me through it, Melissa drew some little thumbnails of spreads with panels and sent them to me as something to try. I immediately saw that Melissa was right about using panels, but perhaps wrong about how to use them—for example, I didn’t think it would work for Cecilia’s story to flip from the background to a foreground panel and then back to the background, or that the panels should be different shapes. And I thought of that Neil Gaiman quote… “Remember: when people tell you something’s wrong or doesn’t work for them, they are almost always right. When they tell you exactly what they think is wrong and how to fix it, they are almost always wrong.” I could see that the panels needed more stability, and that we had to have more horizontal space. And those two insights together were the breakthrough I needed. I reworked the whole draft again as a horizontal book, so that the segments of story text could sit side by side on the page without hitting the gutter. I also pushed the star story into the background to the left and pulled Cecilia’s story into the foreground to the right, where they each stay until the two stories come together— “A star! A scientist!”—and get a full page each. From there, Cecilia’s story takes over on the left page but stays in the foreground, and then they come together and—cheese and crackers—it worked. Melissa and the team at Chronicle loved it and let me run with it, and here we are with our paneled, horizontally formatted book.

BB: Wow! And so much of this depends on the degree to which you concentrate on the science versus the subject’s life. Kirsten, I’m always intrigued by how much of a person’s life one wishes to show. In this case, you begin with Cecilia as a toddler and then decided that rather than end with the end of her life, you finish with the triumph of her big discovery. When writing a biography like this do you always know from the get-go how much of a person’s life you’re going to tell or do you try out different variations?

KL: It often takes me a long time before I know where my story begins, where it ends, and what its heart is. As I wrote this book, I was already thinking about how engineers and scientists work, and how their processes have so much in common with artists and writers. As I read about Cecilia’s life, I felt a lot of familiarity in her powers of observation, her curiosity, and the thrill she got in figuring things out, even when she was a girl. And I could identify with feelings of frustration too. Her curiosity and her persistence were things I knew I wanted to highlight, beginning with that first scene where she was a toddler making a hypothesis about how snow would feel, and being shocked when it was so, so cold.

When I look at the biographies I’ve written, I often like to end with a moment of triumph, but then broaden it so young readers can see themselves in the book. In THE FIRE OF STARS, I show how Cecilia’s discovery paved the way for future questions and answers about the stars, and muse on who will make the next discoveries. I want kids to be inspired and see that science is never finished – there are always new things to discover.

BB: And, as with making a book, it’s about the choices you make along the way. Speaking of which, Katherine, there are a variety of different ways in which an artist can play with a work of nonfiction while keeping within the bounds of reality. I was particularly intrigued by your use of the color yellow in the book. Throughout, Cecilia is slightly set apart from the others by the various yellow dresses that she wears. Did you choose that particular color for any reason? And is it significant at all that she wears it a little less and less throughout the book?

KR: Yellow is just so bright and happy and iconic, and children almost always use yellow to color the sun. So I thought that this little toddler—destined to become a star herself—would stand out best on the page if I dressed her in yellow. As some of your readers may know, stars come in different colors: the hottest stars are blue at 25,000K (K is for Kelvins) or white at 10,000K, and then as they cool and age over time they become yellow (6000K), then orange (4000K), and then red (3000K). As Cecilia grew up and matured into a brilliant astrophysicist, I wanted her wardrobe to hint at this parallel—yellow to orange to red. I also just loved the way the golds and cadmiums sat beside the sepia tones in brushy marks I used for the stars and for outer space.

BB: Oh dang. I completely missed that her outfits were changing in color alongside the changes to the stars themselves. Color me unobservant. Okay, to restore my dignity I need to ask Kirsten my hard hitting question. I found the choice not to include Cecilia’s name on the cover to be fascinating. Normally a title of this sort would be called something like THE FIRE OF STARS: HOW CECILIA PAYNE DISCOVERED WHAT BURNS IN THE HEART OF STARS or something to that effect. But this book makes you open it to find out who it is about. Was that a conscious choice on your part or was that a move on the part of your publisher?

KL: This is such an interesting observation! Was it a deliberate choice to leave Cecilia’s name out of the subtitle? No. We were trying to choose a title and subtitle that would encourage readers to pick up the book. Ultimately, we felt the nod to the parallel story (FIRE OF STARS), plus a key character trait (Cecilia’s “fire”) along with an explanation of the groundbreaking nature of Cecilia’s discovery was the best approach. And of course, as soon as you read the publisher’s description, the jacket flap, etc. Cecilia’s name is right there. Titles are so, so hard!

BB: So hard! I don’t think there’s an author out there that would disagree with you. Okay, one more art question. Katherine, on a previous book you worked on RED ROVER: CURIOSITY ON MARS you had a chance to do a bit of work with space and skies. Still, it feels like this book really focuses in on the cosmos quite a bit more. What are some of the challenges when rendering space dust, protostars, gas particles and more in art?

KL: I loved everything that I learned about Mars and our solar system when working on Red Rover, but for that art I was focused on the character of the rover and on drawing the surface of Mars, and I didn’t give much thought to the stuff that makes up “space.” So after sorting out all of the design hurdles for The Fire of Stars, I sat down to make some paintings, and then—oh no, you have to be kidding me, NOT AGAIN—I hit yet another wall. I realized that I couldn’t just draw the birth of a star—pencils and brushes on watercolor paper with a traditional approach couldn’t capture all of that energy and motion and incredible violence. I needed a new way to make images, something more raw and direct and wild, and at the same time I needed incredible control—everything had to line up just right so that the page design could work. So I started playing. I used toothbrushes dipped in ink, slammed water and pigment onto paper and let it bleed, sprinkled salt into cloudy washes and scraped it across the page… Then I scanned the layers I liked into my computer and composed the final art as digital collages from all of my hand-made pieces. This collage approach also made it possible to pull some of the space textures into the backgrounds of Cecilia’s world to visually reinforce the telling of two stories at once.

BB: Fantastic. Okay, last but not least, what are the two of you working on next?

KL: In terms of the writing, I’m currently making things hard for myself again with a lyrical nonfiction picture book employing a difficult poetic structure. What can I say? I like to try hard things!

My next two announced books are the graphic novel THE LIGHT OF RESISTANCE, illus. Barbara McClintock (Roaring Brook), the true story of Rose Valland, a French curator turned spy who saved countless precious art works from the Nazis. My next picture book is THIS IS HOW YOU KNOW, illus. Cornelia Li (Little, Brown), a lyrical love letter to science.

And, of course, there are always a thousand other things percolating and in various stages of drafting.

KR: Exactly one month after The Fire of Stars comes out, my next self-authored book, Making More: How Life Begins, will be out from Norton Young Readers on 03/07/2023. The back-to-back timing has left me a little dizzy, but then again it feels so good to have two new books after a big gap in my publishing schedule due to having a baby immediately before a global pandemic (I don’t recommend it). Believe it or not, we sold Making More to Simon Boughton as a two-book deal with How to Be an Elephant before Neighborhood Sharks came out in 2014 (!!!), so this book has been on my mind for a looooooonng time and has changed a lot since it was first conceived. In fact, all of the school visits I did for Elephant, in which students raised their hands to ask about how the baby gets out of its mom, helped me better understand what it is that kids want to know. Making More is my answer to their chorus of questions. I used plant and animal examples to discuss reproduction in a way that’s clear and age appropriate, and I did my best to create a tool for parents to turn this tricky topic into an easy conversation. After that is my second book with Barb Rosenstock—A Place Called Sargasso—which tells the story of a little piece of seaweed growing into a home for other creatures in the Sargasso Sea. Barb and I went to Bermuda together last May to do some research, and I am thrilled to be working with her again. Let’s go STEM books, I just love nonfiction so much!

And that, my dears, is the best possible sentence to end this kind of an interview upon.

I can’t thank Kirsten and Katherine enough for giving these answers their all. The Fire of Stars is out on bookstore and library shelves everywhere right now, so go on out and grab yourself a copy!

To end, let’s watch a trailer for the book that’ll give you a better sense of what all that final art looks like:

Filed under: Best Books, Best Books of 2023, Interviews

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Magda, Intergalactic Chef: The Big Tournament | Exclusive Preview

Fifteen early Mock Newbery 2026 Contenders

When Book Bans are a Form of Discrimination, What is the Path to Justice?

Poetry Gateways, a guest post by Amy Brownlee

ADVERTISEMENT