31 Days, 31 Lists: 2022 Books With a Message

All right. I gave myself a little tiny break there for a couple days with those short lists. Now things are starting to ramp up again, and today’s list is an excellent example of that.

First off, some defining terms. As I’ve mentioned in the past, the whole reason children’s books even came to be here in America was to serve as guides for moral instruction. Actually learning to read? Also a plus, but it was that was almost sidelined by this desperate need to guide children on the path of truth/light early on.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Times may change but often when you hear some celebrity say that they want to write a picture book, too often that means they want to morally instruct the young. This is not, inherently, a bad thing to do. It’s just that too often it’s done poorly.

Today, we look at books that desire to send some kind of a message to kids, and who do so we grace, care, and skill.

And if you’d like to see previous years’ message books, look no further than here:

2022 Books With a Message

Amy Wu and the Warm Welcome by Kat Zhang, ill. Charlene Chua

It’s always funny to say with a really simple picture book that “there’s a lot going on here”, particularly when the story itself is so straightforward. But I really do think that in spite of its straightforward look and packaging, Kat Zhang is whipping a whole host of cultural assumptions and stereotypes into submission. This is a new kid in school book and ostensibly the message is on making the effort to make them feel welcome. But it’s also a story of making new immigrants comfortable. And it’s about language barriers and the assumptions we make when people don’t communicate. All told, it’s playing with a host of thoughts and feelings. In this story Amy Wu has a new classmate who has just arrived from China. Though he doesn’t talk in school she sees him talking a lot with his own family, so she tries reaching out. There’s this great moment in the book, though, where she wants to say “Welcome” in his language, but when the moment comes she doesn’t want to do it. A keen example of the putting-yourself-in-someone-else’s-shoes reality.

Beautiful You, Beautiful Me by Tasha Spillett-Sumner, ill. Salini Perera

You know, this “Message” list would be a lot bigger if I included every book on positive self-reinforcement that was released this year. But how many are good? Or original? Or highlight a problem a lot of kids go through but that they don’t actually see in their literature? Too few. Fortunately, some rise from the pack. For example, I found the central conflict of Beautiful You, Beautiful Me to be an especially touching one. In this story we follow Izzy. She’s just old enough to start noticing that her hair and eye/skin color is different from her mama’s. And since she thinks her mama is one of the most beautiful people ever, what does that make her? She wishes she looked more like her mama. Or, in Izzy’s words, they don’t “match”. Now mama here has to do a fairly difficult job of overcoming a kid’s very natural desire for sameness. So I can see a lot of other parents coming to this book for some good advice. Here, the method is to show that not all mamas and babies match in the wild. There’s a little reinforcing chant that goes along with this, and while it’s not quite up to Daniel Tiger jingle standards, I think it could do a lot of good for some families. A hard question meets a great solution.

A Blue Kind of Day by Rachel Tomlinson, ill. Tori-Jay Mordey

“It was a slumping, sighing, sobbing kind of day.” Coen’s having a blue day and when his family can’t cheer him up they wait and let him work through his feelings. This book is definitely vibing on the same frequency as The Rabbit Listened. In both cases you have a central character that’s going through something emotionally, and the people on the outside have to take a step back to allow the person they love some space. On my library’s 101 committee (which included this book on the final list) it was agreed upon that the art is the significant lure here. That’s not knocking the text, which also does a great job. It’s just that the expressions and the body language are all done in a way that kids can relate to. As one of my co-workers put it so well, “It speaks to children without speaking down to them.”

The Boy with Flowers in His Hair by Jarvis

Somewhere I know that someone is teaching a proper course on how to write children’s books on difficult subjects not simply in age appropriate ways (which is important) but also in ways that engage the kids themselves. When we ask ourselves if children get metaphors what we’re really asking is whether or not the act of reading is, in and of itself, important. There’s such a push to make sure that every single picture book out there has some kind of message attached to it. I’m not dead to the irony that I have an entire list on this 31 Days, 31 Lists series dedicated to that idea. But I think it’s possible to say that a book has a message without saying that book has just one message. The Boy With the Flowers in His Hair is a lovely story and supremely simple (which makes sense since we’re talking about the artist Jarvis here). A boy in school has flowers in his hair. One day those flowers start to fall out. So his friends make him paper flowers until is real ones come in. And while we could be talking about a kid with a disease like cancer, we could just as easily be talking about a kid dealing with a difficult home situation or a personal trauma of some kind. This is what I would call an infinitely flexible book. You can read it with purpose, or just read it for what it is: A story about how sometimes you have flowers, sometimes you don’t, and sometimes your friends will help you. Good, no matter what the context.

The Circles in the Sky by Karl James Mountford

One morning Fox finds a bird lying quite still upon the ground. With the aid of a small moth, the two reflect on life and death, accompanied by marvelous, beautiful illustrations. A meditative, contemplative, necessary book. I like my death books touching, and I like ‘em weird. Trouble is, you usually get one or the other. Now this book isn’t fully weird, but it has little tiny elements that keep your attention going. Mountford is making his picture book debut with this title, but you’ve probably seen the work he’s done on middle grade book jackets over the years. Here, he brings his unique style to the story of a fox dealing with the death of a bird. It is very much a story of someone grappling with the idea of death for the very first time. The helpful moth tries out platitudes to soothe the fox, and you can imagine how well that goes. Together, however, they come to a kind of understanding. Now the art in and of itself is amazing. There’s this shot of the fox doing a very foxy straight up-and-down leap in an effort to wake the bird up that’s marvelous (to say nothing of the choice of skeletons under the hill) but the wordplay is the real standout. I love this line: “Sad things are hard to hear. They are pretty hard to say, too. They should be told in little pieces.” Just amazing

Courage Hats by Kate Hoefler, ill. Jessixa Bagley

“Not everyone loves a train. That’s the world. But sometimes, you have to take one anyway.” A girl scared of bears and a bear scared of girls make special hats to feel brave on a train and end up friends along the way. Smart writing and sweet art combine send a magnificent message. Okay, so a co-worker had me read this one and I wasn’t feeling too optimistic about it. I like Jessixa Bagley but something about this cover looked a little too cute for my tastes. Or maybe I was worried that it would contain this super obvious metaphor that offends the intelligence of child readers? Whatever it was, I walked in with doubts. I walked out a convert. First off, this is Bagley’s most sophisticated work to date. She’s really poured her heart and soul into this art. Just examine the way the pages are broken up and the different angles (I love the aerial view of the girl and bear walking down the aisle on the train together). But the real lure is the writing of Kate Hoefler. Do you remember Rabbit and the Motorbike from a year or two ago? Yeah, that’s her. Somehow she has managed to take the old Look Past Your Own Prejudices idea and turn it into this very sweet story that’s entirely new and old all at once. Making a new friend on the train? That’s just fun. But, again, I keep going back to the amazing writing here. This is picture book text at its finest.

How to Hug a Pufferfish by Ellie Peterson

Clever little bugger of a book. Ostensibly the book is about the best way to ask a pufferfish for a hug, but honestly this is about touching people only with their permission. And THAT is a message that I get loud and clear. To be perfectly honest, I’ve always found the concept of touching anyone outside your immediate family without getting explicit permission to do so to be odd. What’s so hard about asking permission? As you might be able to tell, I’m not a natural hugger. Now the pufferfish here has the distinct advantage of not only telegraphing precisely how uncomfortable it feels with surprise/unwanted hugs, but it can also defend itself. Kids don’t have that option, so giving them a book that covers the dos and don’ts of touching other people is great. It might have behooved the book to give the pufferfish some options of what to say to people when they do cross that line, but that’s not actually the audience here. Also, Peterson gets some additional points for figuring out how to stick the landing with that sea urchin at the end. A necessary inclusion.

Hundred Years of Happiness by Thanhhà Lai, ill. Nguyên Quang and Kim Liên

Not every adult author is capable of writing for children. Much along the same lines, not every author of middle grade fiction is capable of particularly good picture books. Some are, though. Some with names like Thanhhà Lai. This Newbery Honor winner has now come up with a subtly simple story of a woman with dementia and the family members that work to create for her the dish that will bring back, if only for a moment, a memory. It’s a risky bit of writing in many ways. Dementia has appeared increasingly in children’s picture books and you always run the risk of making it cute or sweet. Or of downplaying the heartbreak involved. This book reminded me a bit of 2021’s Danish import Coffee Rabbit Snowdrop Lost by Betina Birkjær, ill. Anna Magrethe Kjærgaard, translated by Sinéad Quirke Køngerskov. However in this book there’s a goal in mind. There’s something to work towards. An’s grandmother was wed in Vietnam and at the time ate xôi gẩc (the recipe in the book calls it, or something similar to it, gẩc sticky rice). Much of the book then consists of raising the gẩc fruits, dealing with disappointment when some die, and trying to create this recipe. I tell you, it makes you incredibly hungry to try some of your own, particularly after you read the Note from the Author at the end. And while the food does get a reaction, it’s not a magical cure or anything. But for a moment, it’s enough.

It’s So Difficult by Raúl Nieto Guridi, translated by Lawrence Schimel

Any book attempting empathy, or to really and truly try to get someone to understand how the mind of another human being works, fights an uphill battle. So when I make this list of “Message” books, I tend to look at not simply those titles that are the most adept at fulfilling their own intentions, but also at those books that are able to imbue their storyline with a bit of beauty along the way. I Talk Like a River by Jordan Scott did this. It’s So Difficult does it too. It’s a little Spanish import about a child that has to deal with sensory overload on a regular basis. For him, the simple act of saying “hello” requires an enormous amount of effort. The bio at the back of the book notes that this book was shaped in large part from Guridi’s own experiences as “a secondary school teacher”. Filled with wordless two-page spreads, mixed media consisting of blue inked sheets (timetables? calculations? monetary transactions?) the whole enterprise is a marvelous example of how to convey emotion and a sense of otherness on the picture book page through art and design. Subtle, but not so subtle that a kid’s not going to understand exactly what’s going on.

Last Week by Bill Richardson, ill. Emilie Leduc

I think it’s not an exaggeration to say that I’ve never read a picture book for children about kids spending some final time with a grandparent who will be experiencing medical assistance in dying before. It’s a Canadian import and a gentle one at that. The kid in this book knows that in a week there are 604,800 seconds. That’s how much time he has left to spend with his grandmother, Gran. As he and Gran find ways to talk and remember, the family members go through their own grieving process. Finally, a doctor comes and she’s able to let go with dignity and her loved ones all about her. There are additional resources at the end that explain about MAiD (Medical Assistance in Dying) that might prove invaluable to some child in some family somewhere. As I say, I’ve never seen a book like this before but I am so glad, so glad, that I’ve seen one now.

Loujain Dreams of Sunflowers: A Story Inspired by Loujain AlHathloul by Lina AlHathloul and Uma Mishra-Newbery, ill. Rebecca Green

I kind of wish I’d read this book cold rather than notice the mention of Loujain AlHathloul in the subtitle. If you just take it at face value it’s doing something mildly impossible. I cannot stress enough how it is really really REALLY difficult to write a good picture book about phallocentric patriarchies. The old “girls can do anything” mantra loses a little of its oomph every time it appears in a mediocre book. Yet we desperately need such stories since the situations that inspire them still exist. What Lina and Uma have done here is turn Lina’s sister, Loujain’s, life into a bit of a metaphor. It’s about a girl who wants to fly and has wings, but is forbidden from flying because it’s not what girls are supposed to do. Now this endeavor is helped mightily by the art of Rebecca Green (who, to my mind, isn’t being given enough jobs these days). As far as I can tell, the whole reason it works is that it’s just a little bit weird. The Loujain of this story wants to fly to a place that’s filled with sunflowers (and apparently is loaded down with hidden cameras). In the back you get a note about the real Loujain in Saudi Arabia, and how this is a book about her insistence that women be allowed to drive. I think this book ultimately works because it doesn’t get so wrapped up in its own messaging that it forgets to make a good story along the way. Also, when was the last time you read a children’s book about women prosecuted for driving in other countries? Odd and wonderful.

My Brother Is Away by Sara Greenwood, ill. Luisa Uribe

Books about a loved one incarcerated are almost always about a child’s parents. Which makes a great deal of sense, but it does leave out a large swath of the readership that have older siblings serving time. What they have to go through is reflected in Greenwood’s tale, based on her own life. There’s a nice Author’s Note at the end, showing her when she was in first grade, the time when this story takes place. I would have appreciated a small list of resources for parents when talking to their kids about their incarcerated brothers and sisters, but the tone of the title almost makes up for it. It’s very straightforward and calming. It shows the problems (like a friend in school calling you out for having a brother who did something “bad”) and ends with both the reassurance that the brother still loves her and the fact that she’s not the only kid whose “brother is away”. Nicely done.

My Own Way: Celebrating Gender Freedom for Kids by Joana Estrela, adapted by Jay Hulme

To be perfectly honest with you, I had no idea at all that this book was a translation of any kind when first I picked it up. It’s an interesting title as well since it slot very neatly into a gap in our collections that we’ve had for years. I’ve a friend who is always on the lookout for books that buck the binary (and if we get enough of these titles then that is what I’m naming my display of them). Hulme’s like the Portugese Todd Parr. He dwells in bright colors, simple faces and bodies, and ideas made simple. The book is perfectly straightforward. “Boy or girl doesn’t cover everyone / You might be both. You might be none.” I like it when a book can spell out something in a way that’s concise and obvious. This one is going to be hugely adored by wide swaths of people. It may even become a board book someday. Great messaging from an unfamiliar source.

Out of a Jar by Deborah Marcero

Interesting. You know, I think I might like this book better than its predecessor In a Jar. I’m always rather fascinated with any book that dares to teach something to kids that adults themselves often don’t understand. Marcero just goes all in with the messaging on this one: Don’t bottle up your emotions. Don’t do it figuratively. Don’t do it literally. Seriously, just don’t do it. Mind you, the true star of the show is the art (those wavy endpapers undulate before your eyeballs if you look at them just right). I’m a fan of the creative choices made in the art from page to page, often unpredictable but never at odds with the storytelling. Consider this a kind of modern day Pandora’s Box. Or, rather, Pandora’s Bottles.

The Talk by Alicia D. Williams, ill. Briana Mukodiri Uchendu

I’ve been wracking my brain, trying to come up with other picture books that tackle the notion of “the talk” that Black parents have to have with their kids about being safe in a racist world. I could think of quite a few middle grade titles (my personal favorite being The Talk: Conversations About Race, Love & Truth) but few on the picture book side. And this isn’t to say such books can’t be made, but to make one takes a great deal of finesse. It’s a remarkably difficult topic to broach for younger children. Children who would get the talk tend to be on the older side, so Williams takes the clever tactic of starting her main character off as younger. Then, as he ages, you see some subtle changes and shifts in both the parents, neighbors, and grandparents who care for the kids and in the white adults who most clearly and definitely do not. When “the talk” does at last happen near the end it’s portrayed as a two-page wordless spread, allowing parents who read this book with their own kids to explain each of the instances shown. Some are pretty obvious and some are kind of oblique (the kid on the bench?) which I actually appreciated. It’s not all spelled out for you. A smart take on a hard topic.

Tanna’s Lemming by Rachel and Sean Qitsualik-Tinsley, ill. Tamara Campeau

Inhabit Media has a tendency to specialize in Inuit stories that come from lived experience. And while I always make a point to try to read everything they put out, this book in particular struck my fancy. Stories in which a wild creature is taken into a home, and things turn out poorly, are always enjoyable on some level. I just don’t think I’ve ever seen it done with lemmings before. I don’t think I’d ever actually seen what a lemming really looks like either. One glimpse and you completely understand why Tanna would believe that that little itty bitty fuzzy thing could hardly survive the harsh winters on its own. It’s only when her lemming (named Fluffi) eats through her mother’s collection of silk cloths that she understands that she has to let Fluffi go. I found the art almost had the feel of a throwback. Like it was something Brinton Turkle could have done in the 70s. Utterly engaging, this is my new favorite don’t-take-critters-into-your-houses lesson in picture book form.

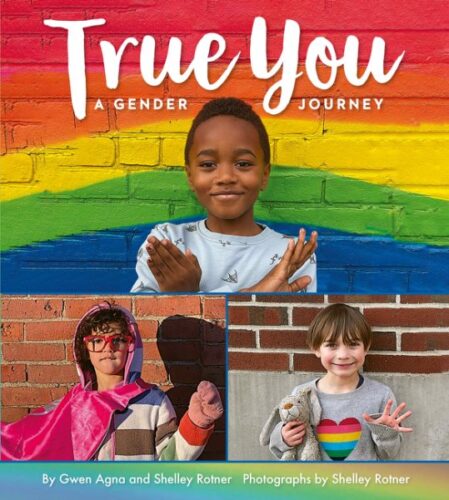

True You: A Gender Journey by Gwen Agna and Shelley Rotner, photographs by Shelley Rotner

I puzzle and puz a bit on why one book with a message for kids may work while another does not. By my estimation much of it comes down to sincerity. If you’re writing a book for a paycheck then that’s gonna seep into everything you do. But if you actually care about the subject matter, do your due diligence, finish your homework, show your work, and mean what you say. Gwen Agna does her homework. Shelley Rotner definitely does her homework (and has the paper trail to prove it). Together they’ve created this exceedingly simple book on gender expression. But writing a book of this sort, with simple text and bright colorful photographs of lots of kinds of kids, is actually just step one. You write this secure in the knowledge that a lot of the learning being done when it is read will be done by adults. So that takes you to the backmatter, where you must include a note to parents, like the one here alongside one for kids titled, “But How? For Kids Finding Out Who They Are”. Now let’s include a “Letter from a Grown-up Trans Girl” alongside a “Letter from a Family”. We’re not done. Agna and Rotner know for a fact that this book is going to be challenged in a library somewhere. So we’re putting in “A Introduction for Caregivers, Educators, and Loved Ones of Children on the Gender Spectrum.” Now an informative section on how language evolves with some transgender terminology suggestions. We’re NOT done yet, people. Here’s a section called “Therapeutic Support”, an extensive Glossary, and a marvelous listing of Resources & Sources. But at the end of the day how good is the actual book for kids? It’s great. Fun and uplifting. Clarifying and supportive. A book that could be a standard bearer for others, going forward.

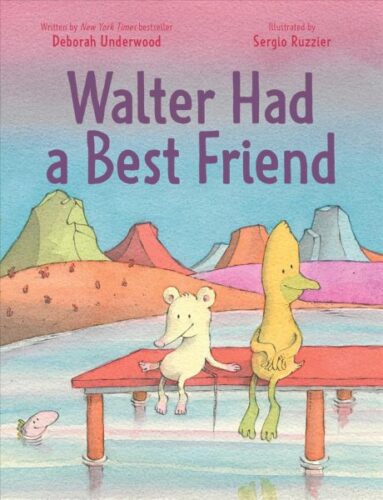

Walter Had a Best Friend by Deborah Underwood, ill. Sergio Ruzzier

It feels kind of gutsy to write a picture book where you honestly tell a child that sometimes friendships just don’t last. Children’s literature is inundated with the opposite message. Time and again the storylines will show a friend growing apart, only to return at the end to the main character. This book doesn’t do that. Underwood is honest in the fact that Walter “had” a best friend. The cover is rather clever too. The former best friend is already looking off into the distance at someone else, while Walter sits there, oblivious. It’s heartbreaking but maybe hopeful for a kid going through this same thing. After much consideration I realized that Underwood and Ruzzier’s latest is not dissimilar in the least from Charlotte Zolotow’s The Best Friend (republished last year with new art by Benjamin Chaud). The two would pair perfectly together, since they both come to rather similar understandings. Consider both when recommending.

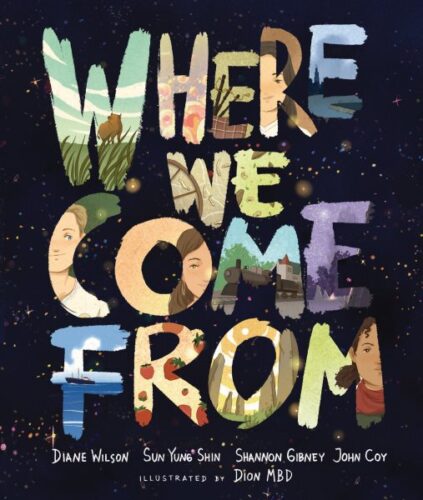

Where We Come From by Diane Wilson, Sun Yung Shin, Shannon Gibney, and John Coy, ill. Dion Mbd

Ambitious little picture book, this one. I’d heard about it a while ago but had forgotten its existence until it fell into my lap. The essential premise at work here is that these four authors are answering that old question “where are you from?” But they’re not going to stop at their stories or their parents stories, but are going to go back in time. And that’s established pretty much right at the start with the opening words “We come from stardust”. Bam! We’re off! It then notes that every person on this Earth “comes from story”. Four of those stories are told. They involve the Dakhóta, Korea, Scotland, and the western coast of Africa. Then there’s a section at the end to tackle the “Where are you from?” question and what to do with it. This book is an answer in and of itself, but it may take multiple readings to sink in. Further Reading and a Selection Bibliography, along with a pronunciation guide and more information about each of the sections mentioned is included at the end. As I say, it’s ambitious and may do a lot of good in time.

Where Is Bina Bear? by Mike Curato

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Bina’s friends have thrown her a supercool party. The only problem? She fears parties so much she runs and hides. Okay. This one’s so very simple that I had to sit with it a little while to appreciate what it is that it’s doing. It really does remind me, to a certain extent, of The Rabbit Listened (can you tell I find that book to be the standard bearer of Message Books?). Possibly because it involves a rabbit listening. I mean, this is about being there for your friends when they need you. And the bunny of this book isn’t insisting that Bina step out of her shell. Nor does it try to force her to have a great time. Lots to love here. Besides, who hasn’t been a Bina at some point in their lives? I can distinctly remember parties I’ve been to where I’ve wished that I could become one with the furniture.

Why? by Taye Diggs, ill. Shane W. Evans

Oo. Can you imagine if the words Diggs put into this book had appeared in Smoky Night, the Eve Bunting Caldecott winner of 1994? That book was attempting to explain the L.A. Race Riots to kids and I would LOVE to read a modern interpretation of that book in light of titles like Why? This book dares to answer questions that a lot of white adults probably don’t want their kids even asking. What I like about it is that it respects the child. Kids ask hard questions and sometimes we don’t want to honestly answer them. This book does, and (more importantly almost) it helps give adults the words that maybe they don’t have themselves. Can you think of any other book that would dare to ask “Why are those buildings burning?” and then explains the rage that comes “When we get tired of shouting and not being heard, when we have cried so many tears from always getting hurt, when we scream out for help and continue to get ignored, when we march and march and march but are not really moving -” Foof! This book has a lot to say. Let’s see who’s listening.

The Wishing Balloons by Jonathan D. Voss

I know we’ve seen a variety of picture books cover this topic, but the way I look at it, this book is only tangentially for kids. You know who else is going to get a lot out of its message? Adults. In fact, I’d wager that the more grown-ups that read this book there are, the wider this very important message will travel. And the message in question? Sometimes someone is sad and your job isn’t to cheer them up. Your job is to be there for them in whatever capacity they would prefer. To simply be there for them. And it’s funny because at first this book sort of sets you up to believe that it’ll be like all those other books about someone being sad and someone else cheering them up at the end. When the heroine of this tale, Dot, hears that Albert doesn’t want anything but his father back, she realizes right away that she can’t do anything about that fact. So there are sequences of her going over to his house and just sitting with him quietly. And the seasons pass and slowly they start to become friends and it’s just this really lovely sequence done in the thickest of oil on gessoed paper. It’s so nice to see Voss doing more of his own books. This one? Very necessary and particularly well done.

You Ruined It by Anastasia Higginbotham

A book for children about what happens when you’re sexually abused by someone close to you. Not an easy topic. Not for every child. There are no depictions of violence. Everything that occurs on the page happens after the fact, and deals with the messiness and complicated feeling after. It’s a hard book to summarize though, so I suggest you follow the link in the title and read my review of it. And truly, this is different from a lot of other books for children out there. Children’s literature began in this nation with the twin purposes of instruction and moral guidance. We’ve moved a long ways from that, but to a certain extent this is a book that guides in its own way. A messy, complicated, unique, necessary creation for those who will need it most. Books for children are not a monolith. They have a wide variety of purposes and jobs. Determining those purposes? That is up to you.

Want to see other lists? Stay tuned for the rest this month!

December 1 – Great Board Books

December 2 – Picture Book Readalouds

December 3 – Simple Picture Book Texts

December 4 – Transcendent Holiday Picture Books

December 5 – Rhyming Picture Books

December 6 – Funny Picture Books

December 7 – CaldeNotts

December 8 – Picture Book Reprints

December 9 – Math Books for Kids

December 10 – Gross Books

December 11 – Books with a Message

December 12 – Fabulous Photography

December 13 – Translated Picture Books

December 14 – Fairy Tales / Folktales / Religious Tales

December 15 – Wordless Picture Books

December 16 – Poetry Books

December 17 – Unconventional Children’s Books

December 18 – Easy Books & Early Chapter Books

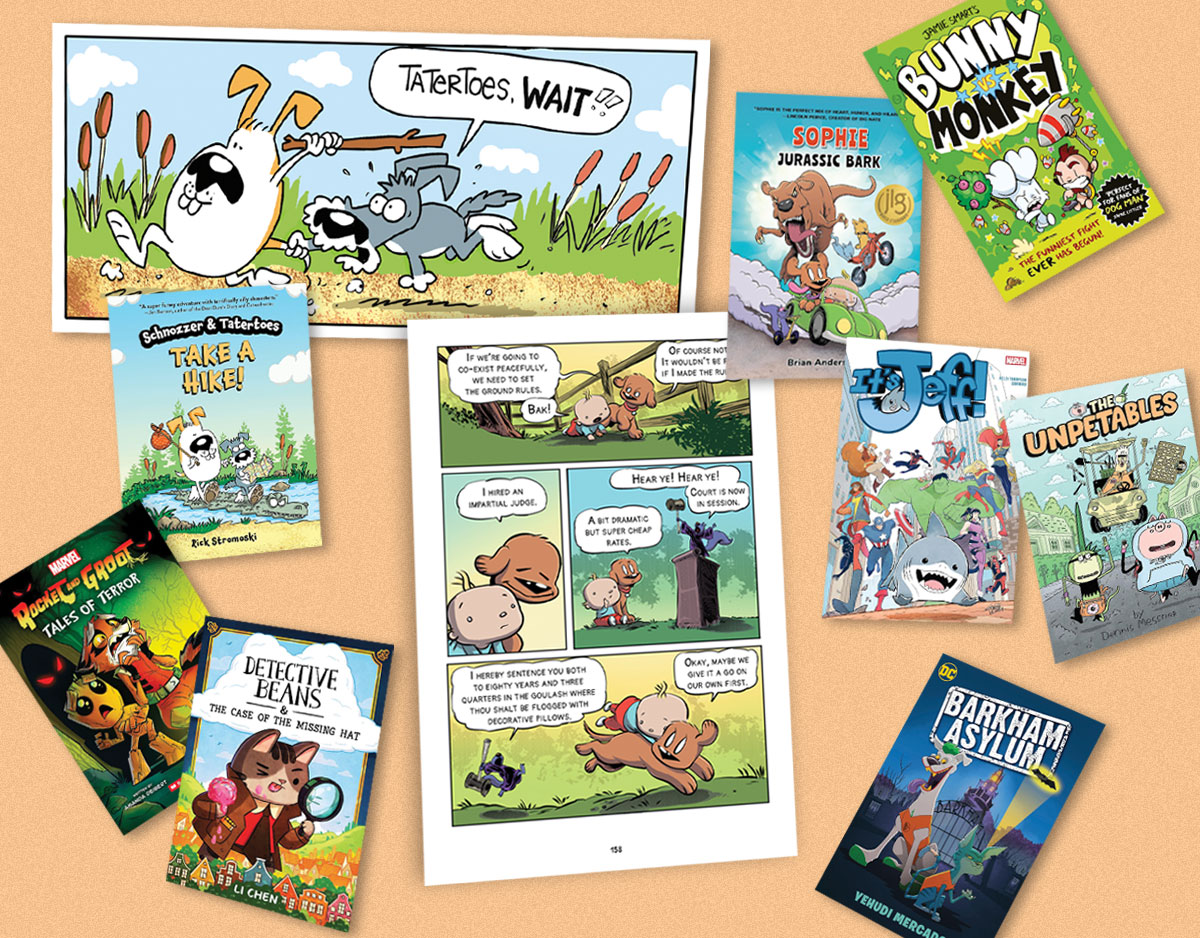

December 19 – Comics & Graphic Novels

December 20 – Older Funny Books

December 21 – Science Fiction Books

December 22 – Fantasy Books

December 23 – Informational Fiction

December 24 – American History

December 25 – Science & Nature Books

December 26 – Unique Biographies

December 27 – Nonfiction Picture Books

December 28 – Nonfiction Books for Older Readers

December 29 – Best Audiobooks for Kids

December 30 – Middle Grade Novels

December 31 – Picture Books

Filed under: 31 Days 31 Lists, Best Books, Best Books of 2022

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Should I make it holographic? Let’s make it holographic: a JUST ONE WAVE preorder gift for you

Magda, Intergalactic Chef: The Big Tournament | Exclusive Preview

Fifteen early Mock Newbery 2026 Contenders

When Book Bans are a Form of Discrimination, What is the Path to Justice?

Poetry Gateways, a guest post by Amy Brownlee

ADVERTISEMENT

I really appreciate the acknowledgement of “do so with grace, care, and skill.” I honestly dislike most celebrity written books, as I feel they are just done poorly!

Out of a Jar was one of my favorites this year. School counselors I work with found this book very helpful with their students. It acknowledged that all emotions and feelings have a place–which is something I think kids need to hear more often.