“Provocatively Nuanced”: The Humanizing of Jackie Robinson

Blessed be the children’s book creators that get that kids can comprehend nuance. And alas that so few do.

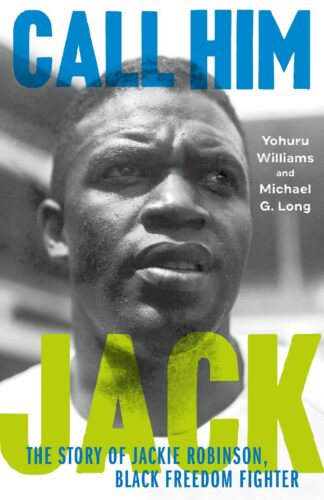

If you were skimming through your PW Children’s Bookshelf newsletter yesterday like me then you might have seen an article in there of note. ‘Call Him Jack’: Jackie Robinson Museum Tour it read. Inside it recounted a recent trip that publishing and library professionals took to the Jackie Robinson Museum located in New York’s Hudson Park. The occasion? The release (as of yesterday) of the middle grade biography CALL HIM JACK by Yohuru Williams and Michael G. Long.

I’ll admit that when I heard that there was another Jackie Robinson biography out for kids I was not impressed. What more is there to say? The man was noteworthy but haven’t all the biographies for kids that have come before covered him sufficiently? Williams and Long make the case that no, they have not. Or, as Kirkus said of the book in their review, this title, “Adds provocative nuances to the usual portrayals of a heroic American.” In short, it shows the activism of Jackie and it show his bull-headed side as well. And THAT was interesting to me. I’ve no time for saints, but give me a hero with flaws as well and you’ve got my eye.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

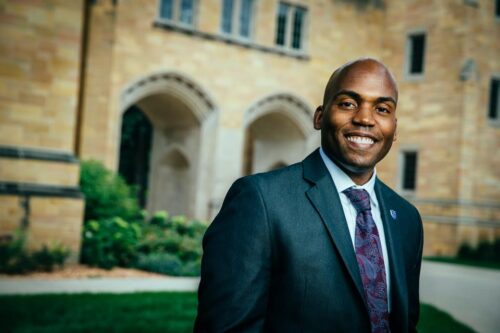

Today I talk with Yohuru and Michael about the book, its impetus, Jackie’s legacy, and what it takes to write a “myth breaker”.

Betsy Bird: Yohuru and Michael, thank you so much for taking the time to talk with me about your latest. Now when I walk into a children’s library and make my way to the biography section, Jack(ie) Robinson is probably one of the better represented folks there. Maybe more so in the picture book bios than those for the 10-14 year old set, but there are still quite a few books. As Robinson scholars yourselves, what inspired you to write CALL HIM JACK for this particular age range?

Yohuru Williams: After surveying many of the books on Jack, we felt it was especially important to write a book about Jackie Robinson that elevated him among the pantheon of African American freedom fighters by recasting the familiar narrative around his integration of the Dodgers through the lens of the human being at the center of that important historical moment. We wanted to decouple Jackie Robinson, the myth and invention, from Jack Robinson the person. Young people in that 10-14 year old age demographic are complex individuals. They understand and appreciate contradictions and nuance perhaps better than anyone–because their lives at that age are very much centered on navigating similar challenges of principle and identity. I know–I taught 9th and 10th graders early in my career in Washington, DC. They ask tough questions and they long to see the humanity in their heroes and role models–as they struggle with finding their own path and sources of inspiration. With the contemporary conversation focusing on athletes and social justice, we felt it was important to show that Jack was not only a baseball player but a freedom fighter–all his life. He was not drafted into the civil rights movement by virtue of his pivotal role in the desegregation of Major League Baseball. Fighting for equal rights was an integral part of his personhood, and he did this with the Dodgers and in every other place he went throughout his life–making less seismic but nonetheless significant change along the way.

Michael G. Long: I agree with Yohuru about the desperate need for a myth-breaking book about Jack, and I trust our young readers will find in our book a Jack Robinson they never knew about, a Black man who fiercely fought for freedom as a child, a youth, a Major League Baseball player, and, yes, a civil rights leader. May I say a bit more about why the middle-grade audience? For me, the answer is personal. I was ten years old when I overheard Mr. Stroup, my fifth-grade teacher, who was famous for cleaning his ears with no. 2 pencil erasers, encouraging my best friend Dean to read biographies. I had a competitive spirit and wanted to keep up with Dean, so on the next trip to the school library, I checked out some biographies of famous leaders in US history. (I’ve since learned the books were part of the “orange biographies” published by Bobbs-Merrill in the 1940s and 1950s.) I’d never been a big reader, but oh my goodness, I was hooked. After my family went to bed, I’d bury myself in the corner of the couch, just under the standing lamp, and travel back in time with George Washington, Betsy Ross, Thomas Jefferson, and more. Those wonderful nights of turning the pages until midnight marked the beginning of my interest in US history and my identity as a reader of nonfiction. So my answer to this part of your question isn’t about Robinson as much as it is about my fervent hope to provide middle-grade readers with a similar experience of feeling embedded in the past and inspired by someone who changed history for the better. I want middle graders to love history as much as I did, and to apply the lessons of history to today’s challenges. Unfortunately, the challenges Robinson faced – racism, police violence, economic injustice, and more – are still with us today.

BB: When Kirkus reviewed CALL HIM JACK it happened to mention that the book contained “provocative nuances”. Aside from that being my new favorite phrase, would you personally agree with that assessment of your title?

YW: I chuckled when I read that as well. I am not sure we were trying to be provocative. We simply wanted to give young readers an opportunity to meet the man behind the legend–unencumbered by the need to deify him in the process. Too many times historical figures morph into superheroes who barely resemble the ordinary people who had the strength and courage to do extraordinary things in their lives. We wanted to write a book about a person who should be very accessible to young people, especially in this moment, when they are faced with very many challenges and questions similar to what Jack faced.

ML: Yep, I smiled when I read that phrase. The Jack Robinson I grew up with was the polite second baseman who “turned the other cheek” when breaking the color barrier in Major League Baseball. He was a nice Black man who integrated baseball. There wasn’t much more to him than that. So imagine my surprise when a bit of research revealed a Jack Robinson who was not nonviolent, who believed in fighting back (sometimes with his fists), and who was rightly angry with white people who denied Black and Brown people the fruits of first-class citizenship. Really, it was as if I was encountering Robinson for the first time. He was more than a smiling baseball player; he was also a fiery personality who fought for justice before, during, and long after his career with the Brooklyn Dodgers. This Jack Robinson was far from one- or two-dimensional. Like our book, he was provocatively nuanced!

BB: The title of the book is, in and of itself, interesting. Right from the start you’re calling him Jack rather than Jackie. Moreover, you’re using that name to make a point about how we frame history. Can you talk a little bit more about that?

ML: I didn’t start using the name “Jack” until I heard Yohuru use it in Ken Burns’s excellent documentary, Jackie Robinson. I’ve since followed Yohuru’s lead, and with good reason. When he was a young boy, Jack Roosevelt Robinson called himself “Jack,” and in high school, college, army, and the minor leagues, he signed his name as “Jack.” So when Yohuru and I call him “Jack,” we’re reflecting, and respecting, his own language. But there’s more to the story. In 1947, after Robinson debuted with the Dodgers, he typically referred to himself, in public, as “Jackie”—which is the name that Dodgers manager Branch Rickey and sportswriters, Black and white, bestowed on him—and from then on, only Rachel and their closest friends called him “Jack.” That gives provocative nuance to the story! By using “Jack,” Yohuru and I aren’t pretending that we’re his close friends. We use the name as part of our concerted effort to unfreeze Robinson from the baseball diamond, where players often refer to one another by putting an “ie” on the end of their names (“Let’s go, Jackieeee!”), especially so that our young readers can see Jack as the important civil rights leader he was long after baseball. Yohuru and I also use “Jack” to unfreeze him from 1947, when he seemed so safe, so unthreatening—so unlike the fierce Black freedom fighter he always was. I don’t want to overstate the point, but in some ways, the name “Jackie” infantilizes Robinson and softens his character to make him more palatable to people who like their heroes uncomplicated, un-nuanced, and nice and sweet.

YW: I would agree with Michael. On the occasion of his induction into the Baseball Hall of Fame, the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. described Jack as a “sit-inner before sit-ins, a freedom rider before freedom rides.” We thought it was really important to introduce the readers to this Jack from the beginning, rather than the more familiar Jackie readers may think they know through books and movies that focus primarily on the integration of baseball.

BB: The time has hardly been better for reexamining the history we’re teaching our children. Too often a historical figure is reduced to a series of easy to repeat stories for kids. The more complicated elements are polished away with the belief that kids can’t handle knowing that someone can be both heroic and, sometimes, have opinions that we don’t always agree with. When putting this book together, how did you decide what elements to leave in Robinson’s life and what to take out?

ML: One of my favorite parts of the book is a photograph of Robinson kicking his glove high into the air. I love that picture because it humanizes him so much. It shows that our hero, our national icon, had moments of intense frustration, just as we do. That’s what we looked for—material that showed Jack in his full humanity. One of the most challenging parts of the selection process was the sheer volume of material. Robinson was involved in so many things—sports, civil rights, politics, entertainment, business, and more. Heck, he even had a men’s clothing shop in Harlem! Beyond considering what was age-appropriate (and not all Robinson stories are appropriate for a middle-grade book), we chose topics that allowed us to tell a good story. His baseball stats are fascinating, for example, but more compelling is the story of Jack leaving behind the “turn the other cheek” period and directly battling those who assaulted his dignity. We were also focused on material that showed Robinson fighting for Black freedom in his childhood and during the civil rights movement, two periods that are often downplayed in Robinson books. Because of this, we felt free to exclude some material from his baseball years.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

YW: I couldn’t agree more. It is very important to emphasize this for young readers. There was a time when the biographies of great individuals were molded into simple morality tales to highlight the character and virtues of the subject. In the process, this transformed ordinary women and men into superheroes who seemed beyond the grasp of young people. Reimagining the way that we talk about historical and heroic figures to encompass elements of their humanity, including their flaws, not only makes them more accessible but relieves young people of the expectation and burden that in order to do something meaningful or substantial, they need to be perfect. Jack Robinson was far from perfect, but through the strength of his conviction and the leveraging of his athletic ability and intellect to push for civil rights, he helped to transform the nation. Through his story, every young person can learn that they can also have the same impact–even if in smaller ways–by staying true to their convictions and working toward justice.

BB: Finally, do you have any inclination to make other books for kids?

ML: I love working with Yohuru. We share an enthusiasm for telling stories about civil rights, and we bring such different perspectives to the table. His use of “Jack” is a perfect example of the way that his perspective has energized me and helped me grow as a thinker and writer. We’re hoping to make other books for young readers, especially ones that will inspire them to become freedom fighters in their own communities. Yohuru and I certainly have more great stories to share!

YW: Absolutely. Working with Michael was a pleasure, and there is so much history yet to be explored for young readers. We already have plans to work together again. We agree that young readers need books and stories that not only introduce them to inspiring historical figures, but invite them to imagine a world in which the challenges those individuals faced, such as racism, can be eradicated, and to begin reflecting on how they can be part of that change.

Now that’s what I call an interview.

I want to thank Yohuru and Michael for taking the time to respond to my questions so thoughtfully. Thanks too to Morgan Rath and the folks at Macmillan for the opportunity to dive a bit deeper into this release. CALL HIM JACK is on bookstore and library shelves everywhere as of yesterday. Be sure to give it a read.

Filed under: Uncategorized

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

The Moral Dilemma of THE MONSTER AT THE END OF THIS BOOK

Winnie-The-Pooh | Review

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

ADVERTISEMENT