Helping Readers Connect With Stories: An Interview with Prolific and Amazing Lawrence Schimel

In May of 2022 you may have seen an article in School Library Journal entitled State of Global Kid Lit: An Industry Impacted by War, COVID, Is Flourishing. The piece took a deep dive into the Bologna Children’s Book Fair (the largest international rights fair of children’s literature in the world) and along the way the author of the piece (whose name rhymes with “Metsy Murd”) interviewed editor, translator, and author Lawrence Schimel for his insights.

To celebrate this year’s #WorldKitLitMonth, I think that this is a person you should probably meet. We discuss translating puns, how to avoid gendering characters, shifts in public perceptions of translation here in the States, and what happens when your same-sex family board books are simultaneously attacked by the governments of Hungary and Russia.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Betsy Bird: Lawrence! Such a delight to speak with you again. I haven’t seen you in person since the Bologna Book Fair back in March. I see too that you’ve been keeping busy. But before we get into any of that, could you give us a bit of a rundown on your career, specifically as a translator of children’s literature?

Lawrence Schimel: Great to have this chance for a dialogue, Betsy!

photo credit: Nieves Guerra

I’m actually preparing a little catalogue of books I’ve translated (actually two, one for books translated into English and one for books translated into Spanish) in preparation for the upcoming Frankfurt Book Fair, where Spain is the guest country. So I just happen to have this kind of overview of my career at hand!

I managed to fit 68 titles into the catalogue of translations into English and 45 titles into the catalogue of translations into Spanish. This doesn’t include everything, and there are some new projects that’ll have to wait for a future catalogue due to space reasons. But it’s most of what’s been published already.

Of these books, picture books are in the lead (51) although poetry collections are close behind (45) followed by graphic novels (15–although I just turned in another one yesterday).

I’ve always thought of myself as an author who later started translating, but it turns out my first book publication happened as a translator (in 1994, for a graphic novel) before my first book as a writer (my first short story collection in 1997, although I had edited a dozen anthologies before that came out, the first of which was published in 1995, so still after my first translated book).

Even though I have now translated more books than I’ve written or compiled as an anthologist, I think of myself first and foremost as a reader, followed by writer who is also a literary translator.

Translating is different than writing for me; it’s creative and stimulating without being exhausting in the way creation is for me. (It’s interesting talking to others who create in multiple languages about the question of self-translation; it is different than translating a finished, concrete work–with all the creativity we can bring to it–because the work goes back on the worktable as a work-in-progress, as creation–even if this time in the other language–rather than re-creation, as we do when we’re translating.)

Focusing specifically on books for young readers:

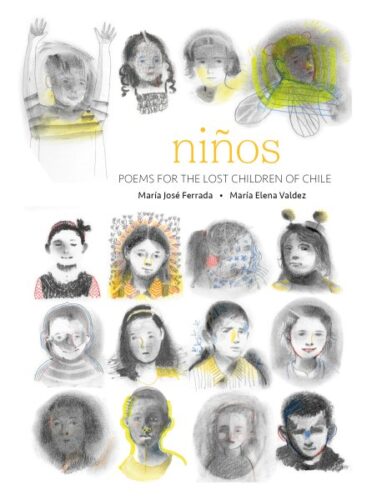

Into English I’ve translated middle grade novels like THE TREASURE OF BARRACUDA by Llanos Campos (Sourcebooks) and THE WILD BOOK by Juan Villoro (Restless Books), picture books like THE DAY SAIDA CAME by Susan Gómez Redondo, illustrated by Sonja Wimmer (Blue Dot Kids) and SOME DAYS by María Warnicke (CrossingKids), and poetry collections like NIÑOS: POEMS FOR THE LOST CHILDREN OF CHILE by María José Ferrada, illustrated by Maria Elena Valdez (Eerdmans).

Into Spanish I’ve translated works like Wanda Gàg’s picture book MILLIONS OF CATS (Libros del Zorro Rojo) or George Takei’s graphic novel memoir THEY CALLED US ENEMY (Top Shelf).

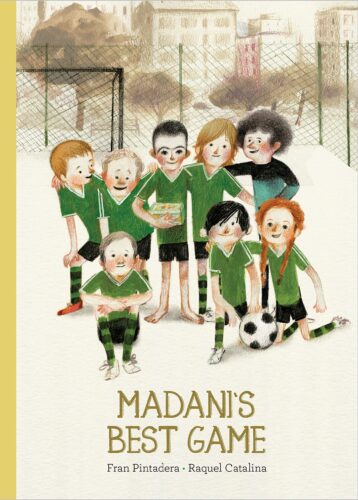

BB: I see too that you’ve translated MADANI’S BEST GAME, the art of which was discussed at the last Bologna Book Fair as being some of the best in the world. It’s a title with a specific kind of flair and pep. When you translate, to what degree do you have to work to capture not simply the message of the book but the tone too?

LS: All translation is that juggle between recreating both the content and how it is conveyed (all the nuances of tone, register, any formal elements like rhyme, etc.)

Translating picture books has a third element that comes into play, which is the artwork.

Not only can you not contradict the content of the art, but you need to make sure the tone of the text matches.

The best picture books are, of course, that marriage of text and art, and with both a textual narrative but also a visual narrative taking place simultaneously.

And sometimes it’s necessary to tweak the art, when there is text on signage. (Sometimes it is left as is, when the location is important to the story and those untranslated signs contribute to ambiance and let readers know where the story is situated. But other times, those signs provide important information to the reader that needs to be translated and either redrawn or handled with a new font or something. The signs in MADANI’S BEST GAME are all translated.)

In translating MADANI’S BEST GAME, it was necessary to not overexplain anything but to let the story unfold on its own. As I recall, we had to break one or two sentences to make sure they remained poetic without being awkward syntax in English.

It was also necessary to make sure all the soccer terminology was correct! And we had to adapt the names and the nicknames of the teams and the players.

I do love the editing process when no one is driven by ego, but just to make the best possible book. When an editor or copyeditor flags something, even if I don’t agree with their suggestion, they’re signaling a place where something is not yet working right. And often, a third solution proves to be just right.

There are also times when I’ll explain why something needs to stay the way it is because of the weight it has or what it is doing in the original, and an earlier or later part of the sentence or paragraph can be changed instead so the English flows or some contextualization can be added to give the reader necessary cultural information they might not otherwise have.

BB: I can hardly expect a translator to have favorites, but are there particular authors or types of titles that you look forward to working on specifically?

There is a certain kind of humor that’s both really tricky to pull off but really fun when one can do so. Agatha Christie once said (I’m paraphrasing) that tragedy was universal, but humor is national. And often there are puns and plays on words that are so language specific. But being able to recreate a similar sort of play on words results in a special sense of accomplishment.

I recently translated PIECE BY PIECE by David & Ferran Aguilar, a middle grade memoir about a boy from Andorra who was born without one forearm. When he was 9 years old, he built himself a prosthetic out of a LEGO set. His dad took a video of a later prosthetic, which went viral, resulting in him being invited to both Legoland in Denmark and NASA, among many other adventures. And while the story recounts a lot of the bullying and abuse he suffered, it is also full of puns and plays on words. And it was important to recreate that in the translation. So when he said, who knew that he would “ir tan LEGOS” instead of “ir tan lejos” (go so far), we wound up going with “who knew that it would be his big brick, I mean, big break.” It’s a different pun, but serves the same function, and is still a LEGO-related joke — one which felt more natural than saying “who knew I would LEGO so far.”

I also admit that I enjoy the challenge of translating rhyming children’s books. I translated into Spanish LITTLE YOU by Richard Van Camp, illustrated by Julie Flett (published by Orca in English and also in my Spanish translation). This is a lovely rhyming book for very young readers, showing different first nations families in different combinations but always being very careful never to assign a gender to the baby being addressed. Which is possible in English but became really tricky in Spanish. Even the title was an obstacle, since all diminutives are gendered. But I didn’t want to just use the masculine as neutral, which Spanish does, when the author was so careful to avoid that in the original. It required taking more liberties to create a rhyming, gender-neutral version, but in doing so, I was able to stay closer to the spirit of the book. I delivered to Orca both a simple translation, without rhyme and using the masculine as neutral, and my gender-neutral rhyming version, which is the one that was published. The new title is TÚ ERES TÚ (You Are You) to avoid gendering the baby.

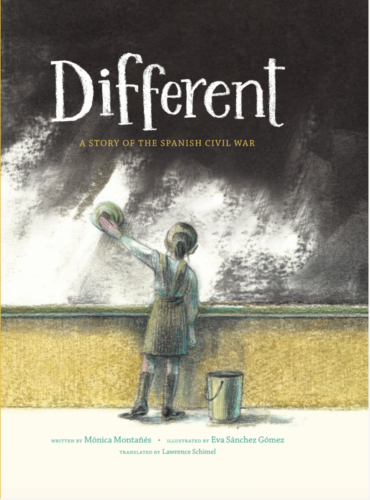

BB: Let’s talk about what happens when you get a book like the loquacious DIFFERENT: A STORY OF THE SPANISH CIVIL WAR. Again, tone is key, but I’m thinking specifically of the increased word count. Do you ever experience a kind of burnout when you translate? Do you have to take regular breaks? Or are you the kind of guy who just plows through a text from start to finish?

LS: There are a lot of questions to unpack here so let me start with tone, although word count is also something very interesting for this particular picture book.

In Spanish, this book was published as a very text heavy picture book with a tiny font size. The American picture book market tends to be very light on text, but in a lot of countries parents want to get value for their money and it’s not uncommon to have picture books with very long wordcounts. But more importantly, given this story, and the tone of the voices, I suggested to Eerdmans to bump it up to a chapter book/middle grade format, which they agreed to do. And I think the book works so much more coherently now. The original publisher actually wrote me recently (In addition to having translated some of their books into English, I am an author of a picture book written in Spanish that they published, which in English is published by Groundwood, LET’S GO SEE PAPÁ! illustrated by Alba Rivera translated by Elisa Amado) that they are now thinking of doing the same thing when it comes time to reprint!).

A lot of tone or register questions are things I wind up discussing with my editors. So for DIFFERENT, I also suggested leaving some words in Spanish (especially some political terms but also foods) and either contextualizing them or including them in the glossary at the end of the book. Kathleen Merz, my editor at Eerdmans, agreed right away. I think it helps give the book a special texture and works especially well because the novel shows and contrasts two different countries which share the same language (Spanish) but have many new experiences and words for them. And a political freedom in Venezuela at that time that was lacking under the Franco dictatorship.

In terms of pacing and burnout: I tend to be a sprinter. So I have intense bursts of activity and then fallow periods. I also love the translating but loathe a lot of the admin around it. But I do enjoy diving into a longer project and have the stamina to work on a long project over a period of time. For fiction, I prefer not to be distracted with other projects, so I can stay in the voice of that work, especially when doing the first draft.

I tend to be a fast first drafter, in part because for projects I hadn’t read beforehand I want to find out what happens next, and so I work more consistently to satisfy that readerly itch. For a book like DIFFERENT, I had written a reader’s report for it, so I had read the whole book before translating it, but it’s still relatively short, especially when compared to an essay (95,000 words) I’ve just finished translating and an adult novel (113,000 words) I have on my plate right now. I also translated the first draft of another adult novel a few weeks ago, it was relatively short (250 pages) so I was able to do the entire first draft in one go (a little over 2 weeks) and it is helpful to have the whole book in my head, as it were, to let it mull, before I go back and revise.

In my quick first draft there are things I’ll jump over, just typing the untranslated word or phrase into the manuscript, and will figure out later on as I keep living with the book. Especially for a novel, it takes a while to settle into the voice. One trick a colleague recommended was to start not with the beginning, which is so crucial, but in some middle chapter (the “muddle” as some writers call it) and then go back to the beginning once you’ve caught your stride. Then you revise that muddle chapter when you hit it again and keep going.

Anyway, I don’t get burnout from working on books themselves, but the whole pitching process can be exhausting, and this is something that often falls on translators to take on. Especially those of us concerned with advocating for voices (women writers, racialized writers, queer writers) who aren’t otherwise being translated as frequently.

It’s wonderful when you matchmake the right project to the right editor so it’s a joy to work on —whether the book is very long or very short.

I am also asked by publishers or agents to translate samples for them, either to help them sell rights (if originating publisher/agent) or to consider buying rights (for anglophone publishers); although, usually I’ll be asked instead to write a reader’s report. And those can be more of a slog, depending on the project, the publisher, what I’d rather be working on, etc.

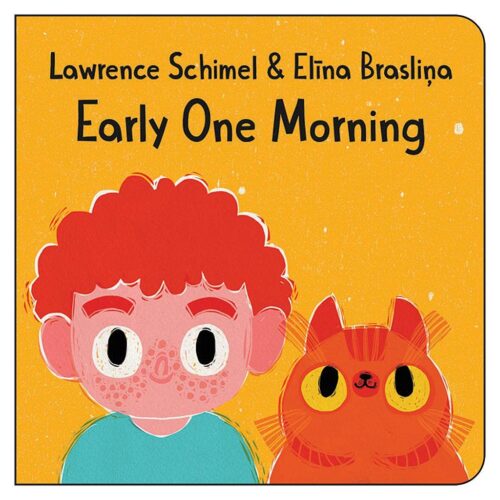

I will say that I definitely did have a period of burnout, as an author not a translator, especially in 2021 when my two board books featuring same-sex families, EARLY ONE MORNING and BEDTIME, NOT PLAYTIME!, both illustrated by Elīna Brasliņa and published by Orca for North America, were attacked by the governments of Hungary and Russia, and all the fallout from that.

It took up a tremendous amount of mental and emotional energy, and every time it seemed like the online attacks had finally died down, there would be another gratuitous outpouring of hate that you couldn’t ever prepare for, and which would knock me for a loop each time. Even though I was fortunate to not live in the countries where the worst of it was taking place.

While I was determined not to let their hate silence me or stop me from continuing to create, trying to just keep up and keep together as all the international news happened around me (and journalists with their own agendas) as the story broke and continued to evolve. Most recently, the Russian state liquidated the NGO that published the books in April, precisely because they published them according to the judgement.

Curiously, I had some of my most prolific and visible moments as an author (ironically during the pandemic and in Spain when we were in strict lockdown) with many international editions of these two and various other books of mine being published, and many books I translated being published (often to starred reviews and awards) at the same time that I hadn’t sold a new project since 2018 and my querying agents (before the pandemic) had not resulted in any interest (and in some cases, not even any replies). I was feeling rather despondent and burned out, even while intellectually understanding that the whole world had gone kaplooey with covid, and nothing was the same anymore.

But the translating, which I find fun and stimulating, was a way to keep helping other readers connect with stories.

For me, translating is kind of like doing sudokus or playing Boggle, half a pastime even when it’s also work.

BB: Since you’ve been translating for the American market for a number of years, I wonder if you’ve seen any perceptible shifts in the American public’s reception or acceptance of these titles since you first started out?

LS: I think it can definitely be seen, even just looking at how some of the publishers I work for regularly, like Orca Book Publishers, have started to include translator’s names on the cover, and how Eerdmans includes the translators’ names even on the promotional bookmarks for their translated titles.

You’re also seeing many more books in translation getting prominently reviewed, even in this day and age with shrinking review coverage, and books for young readers usually getting short shrift.

I think that definitely at the picture book level, where so much is dependent on art, and often non-American art styles serve as a breath of fresh air, there is a lot more openness. Also from publishers, especially those who might not themselves speak another language, because they can base their decisions on the art grabbing them. I think that for middle grade and YA, it’s a lot tougher, and there isn’t yet as much interest in or awareness of work in translation from publishers, the media, or the reading public.

There isn’t yet a Ferrante Fever in MG or YA, and so many classics (THE LITTLE PRINCE, say) are still not thought of as “books in translation” by the American market, but just as “classics.”

BB: I know you do a lot more than translate. So just to close out, what else are you up to these days? And what plans do you have for the future?

LS: Aside from the books mentioned earlier, I’ve got some more translations coming out in the first few months of 2023: picture book 9 KILOMETERS written by Claudio Aguilera & illustrated by Gabriela Lyon (Eerdmans), originally from Chile, about how kids get to school; a middle grade non-fiction book about how the brain works, also originally from Chile, YOUR BRAIN IS AMAZING, written by Esperanza Habinger & illustrated by Sole Sebastián (Orca); a poetry collection written by Afroguatemalan poet Julio Serrano Echeverría & illustrated by Yolanda Mosquera, BALAM AND LLUVÍA’S HOUSE (UK: The Emma Press), which won a PEN Translates Award from English PEN; and a really powerful hard-to-classify heavily-designed book from Mexico, THE BOOK OF DENIAL, written by Ricardo Chávez Castañeda & designed/illustrated by Alejandro Magallanes (Enchanted Lion) that’s not quite a picture book and isn’t a graphic novel either but isn’t just an illustrated middle grade or YA project either.

In terms of my own writing, the aforementioned pair of books illustrated by Elīna Brasliņa are now published or forthcoming in 49 editions in 38 different languages, including Basque, Icelandic, Luxembourgish, Hebrew and isiXhosa. And on a happier note, instead of banning the books, in some countries they’ve even been published by the government itself, like in Portugal, where the Commission for Citizenship and Gender Equality published them in a not-for-sale edition donated free to schools. And the NGO Stonewall Cymru also donated copies of the Welsh edition to all 800 primary schools in Wales.

I do also have some new picture books forthcoming. In Spring 2023, I have a picture book written in Spanish about community, being illustrated by Luciano Lozano, that’s forthcoming from Planeta, and another picture book that will be first published in 2024 in Switzerland (I just got the final German translation from Eva Roth today; the text was originally written in Spanish, and this is one of the tricky questions that arose after we went over the drafts and made changes to make the text work in German, which will be the original publication–will translations be made now off the German text or off the original Spanish?).

And Orca has bought the North American English rights to my picture book ¡QUÉ SUERTE TENGO! illustrated by Juan Camilo Mayorga, originally published in Colombia by Rey Naranjo, which was chosen by IBBY for Outstanding Books for Young People with Disabilities. I self-translated the text into English and have been working with editor Sarah Howden on revisions. It’s scheduled for Fall 2023, probably under the title LUCKY ME.

I am just floored by the amount of time and energy Lawrence took to answer my questions today. I raise a glass in honor of his amazing achievements and the many more to come! Thanks to Amy Burton Storey and the folks at Eerdmans for the idea for this piece. And thanks, of course, to Lawrence for all that he does and all that he is bound to do.

Filed under: Uncategorized

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Should I make it holographic? Let’s make it holographic: a JUST ONE WAVE preorder gift for you

Magda, Intergalactic Chef: The Big Tournament | Exclusive Preview

Fifteen early Mock Newbery 2026 Contenders

When Book Bans are a Form of Discrimination, What is the Path to Justice?

RA Tool of the Week: Inside Out Inspired Emotions, but Make it YA Books

ADVERTISEMENT