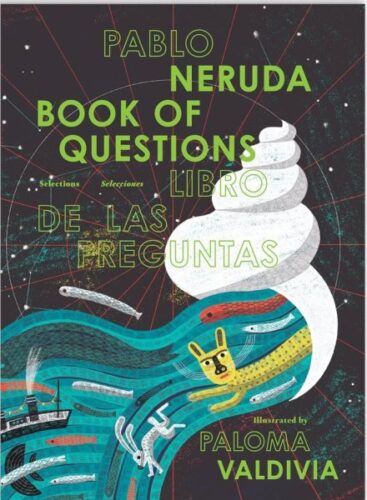

Review of the Day: Book of Questions / Libro de las Preguntas by Pablo Neruda, ill. Paloma Valdivia

The Book of Questions / Libro de las preguntas: Selections / Selecciones

By Pablo Neruda

Illustrated by Paloma Valdivia

Translated by Sara Lissa Paulson

Enchanted Lion Books

$22.95

ISBN: 9781592703227

Ages 7-12

On shelves now.

Small children ask many questions. It’s a rather understandable instinct, to be honest. If you are young and encountering as vast, wide, and mysterious a world as this one, your little human brain may react by wishing to clarify and categorize everything you see. Sheer human necessity dictates an endless stream of questioning. Naturally, it can’t last. Once the children are a little older their questions may not disappear entirely but they certainly taper off. A tad older still and suddenly they consider themselves founts of wisdom. What can this old world teach them when they already know so much? Personally, I’d say that this would be the point to hand them Book of Questions: Selections by Pablo Neruda. A bilingual production, the book is as physically beautiful as it is mentally engaging. For the know-it-alls amongst us, turns out Mr. Neruda still has something to teach us, young and old.

Mere months before his death in 1973, the great Chilean poet Pablo Neruda completed his last great work of poetry. Book of Questions originally contained 74 poems and 320 questions. Now 39 of the 74 poems have been selected, a mere 70 questions arranged thematically. In this context the questions are just parts of poems. Even so, with the aid of Chilean artist Paloma Valdivia, the book creates questions that can’t help but expand the minds of young readers. Even as they enjoy the natural world and geography present in the illustrations, kids and adults will come over and over again to ponder many of these questions and, hopefully, come up with some of their own.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

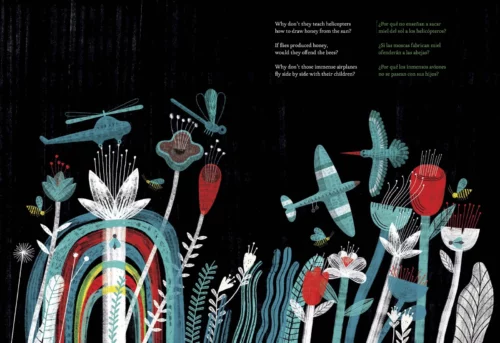

It isn’t as though we haven’t seen children’s books full of questions before. While it’s not quite so common that you’d deem it a trope, it’s pretty standard stuff. You write a picture book full of lightly philosophical queries, then sit back and let some genius illustrate it. Badda bing, badda boom, instant graduation present! And so I offer you this word of warning to the wise: Do not expect this book to follow that well trod path. Here are some typical questions you might find on these pages: “Do unshed tears wait in little lakes? Or become invisible rivers that rush toward sadness?” “Do you hear explosions of yellow in the middle of the fall? If we use up all the yellow, with what will we make bread?” And perhaps my favorite, “If flies produced honey, would they offend the bees?” As an adult I look at these and wonder if these are questions meant to not have answers. But then there’s that other part of me that knows that for some kids out there, their reaction to these questions would be, “Challenge Accepted!” I would pay great heaping gobs of cash to watch some quick thinking children provide serious answers to these queries. Someone go make that video!

Who created this book? That may sound like a flippant question but I’m dead serious. You might say that Pablo Neruda is the true author, these being his questions and all, but he never envisioned in his lifetime a book that looked like this one. Heck, we can only imagine his reaction to finding his poems broken down, decontextualized, and reconstituted as they are here. Is the true creator of this book the illustrator then? She certainly writes movingly in her note at the end of the book of the influence of such locations as Araucania and Bundi Lake. But Paloma never selected which poems would fall onto these pages. It seems to me that the true creator, the person who looked the 1974 publication and saw its potential, would have to be its editor. And since this is an Enchanted Lion Books production, the odds are good that her name is Claudia Zoe Bedrick. Conventions being what they are, you’ll not find her name on this book. Even the Editor’s Note at the end refers to her as simply her title: Editor. Still, her fingerprints are all over this book. A little internet research (particularly from an NPR review) also reveals that the translator Sara Lissa Paulson also had a heavy hand. It says, “in curating the selection, translator Sara Lissa Paulson and editor Claudia Bedrick wanted to highlight those that would be in the realm of experiences that young children are excited to discover. They chose 70 questions mostly related to the relationship between humans and the natural world.” So let us place credit where credit is due (even when the people involved aren’t even crediting themselves).

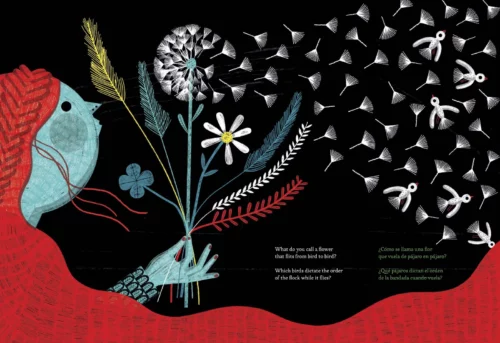

Speaking of the translator, The Book of Questions / Libro de las preguntas is a marvelous window into the state of bilingual children’s book publishing today. We’ve come a long way from the days when a bilingual book meant a picture taking up the entirety of one page, and a white page full of text on the other. Often bilingual children’s literature trades in design and beauty for utilitarianism. Such books still exist, but isn’t it nice to have options? In this title, you can get a palpable sense of the care taken with each and every last one of these pages. Note the color of the English font vs. the Spanish font. Where are the words placed in the context of the images? Is the English kept near the Spanish or is it separated and, if so, why? Generally speaking I was deeply impressed by what I saw on these pages, but I was a bit disappointed that the Spanish language version was so often printed in a green font that had a tendency to blend in with some of the black backgrounds. A person with dimmed eyesight could be forgiven for entirely missing some of these Spanish sections, to say nothing of dyslexic readers. So while I admire the dedication to changing the font colors, I do wish that the Spanish language was as easy to read as the English. Even if that means (gasp!) the two being the same color.

In her Illustrator’s Note, Paloma Valdivia hits on one of the possible frustrations inherent in a project of this sort. She writes: “Illustrating these poems was like deciphering a map of the poet, exploring the territories of his words, looking for meanings in his houses and among his collections, tracing symbolic pathways – only to arrive at understand, after five years of creative labor, that there are no answers, only more questions arising from Neruda’s questions.” A hazard of the job. Images at the back of the book show a little of Ms. Valdivia’s process, but the essential magic is kept hidden from readers. Maybe that’s for the best. I mean, Pablo Neruda’s great and all, but for many of us who weren’t raised on his poems, the real way this book lures you in is through Valdivia’s marvelous art. On a personal level, I was delighted with the frequency with which she would paint scenes against black backgrounds (fonts aside). I started trolling through the professional reviews to see how they describe her style since I couldn’t quite put words to it. Horn Book called it, “a limited, muted palette” which I take a bit of issue with. Kirkus felt a bit more on the nose when they said that the, “stylized artwork . . . feels grounded in folk-art traditions.” Finally, PW calls the art, “dark and mysterious,” and there’s some truth to that. It’s what I love best about it. This is the kind of art that will take root in a child’s subconscious and memories for the rest of that person’s life. It will influence the shape of their dreams. It will seep into how they interpret the world. And if I could plaster it all over the walls of my own home, you can bet that I would.

Shh…. Do you hear that? There . . . there it is again. Do you know what that is? That, my friends, is the sound of thousands of amazing teachers’ hearts as they simultaneously realize the potential curricular applications of this book. And not just elementary school teachers either, I’d add. While the book is certainly the size and shape of a picture book and is marketed to the Grades 2-3, I see far greater potential for it. Imagine units in which kids come up with their own questions. With their own poetry! Now imagine a middle school or high school unit that begins with this book, and then transitions seamlessly into considering the original text. High schoolers could then attempt to write their own poems of three to six questions (“six to twelve lines with each question one, two, or four lines”). I’m not going to say that the possibilities for this are endless. They’re just very very broad.

Poetry for kids has a tough row to hoe. The American Library Association does not have a designated award for children’s poetry alone. Public schools are generally more interested in discussing poetry for brief snatches at a time in April (National Poetry Month) rather than interstitially throughout the year. And translated poetry? Hoo boy. It’s out there but hardly common. But in spite of all of this, I think that The Book of Questions has a number of points in its favor. First off, it’s an absolute beauty to look at. Even its transparent book jackets works in its favor. Second, the very fact that it’s bilingual means that it can only increase its potential audience. And finally, there’s no denying that the name “Pablo Neruda” carries with it some significant sway. Add in the fact that the book is actually fun to read and use and ponder, and you’ve got yourself an eclectic title with great potential. It certainly doesn’t resemble any other poetry book for kids out there, and I’d say that that is a wonderful thing. A little weird, a little wild, hand this book to the child that’s forgotten how to ask questions with the same vivacity they did when they were little.

On shelves now.

Filed under: Best Books, Best Books of 2022, Reviews, Reviews 2022

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

2024 Books from Printz Winners

Exclusive: Vol. 2 of The Weirn Books Is Coming in October | News

Fighting Public School Book Bans with the Civil Rights Act

ADVERTISEMENT