ACTION!: How Books About Movies Get Made – A Meghan McCarthy Interview

A treat. A treat for you, a treat for me, a treat for anyone, anywhere that loves old movies.

Recently I’ve been wracking my brain, trying to think of any books for children that talk about the origins of film. The Invention of Hugo Cabret by Brian Selznick is probably the most obvious example, but there are others out there. There have been picture book bios of Buster Keaton (and graphic novel suppositions about his youth). There have been picture book bios of Charlie Chaplin (and older nonfiction bios as well). But a book that gives you a clear sense of the key points of cinema from the get-go? Such a book does not exist.

Until now.

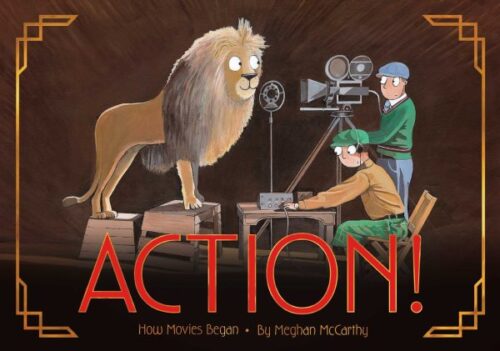

Meghan McCarthy is unafraid of tackling unusual subjects in her nonfiction picture books. The War of the Worlds broadcast. Charles Atlas. The birth of bubble gum. Earmuffs! But until I saw her latest book ACTION!: HOW MOVIES BEGAN (on shelves August 23rd) I had no idea of the intricacies she was capable of producing. If you want a labor of love, and a truly wonderful deep dive into cinematic history with ties to films kids are familiar with, this is the book you have to see.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

A plot description from the publisher:

“Award-winning nonfiction picture book creator Meghan McCarthy tells the story of how motion pictures came to be invented and the story of the many people who helped create them.

Movies take us on adventures, introduce us to new worlds, and make us feel, but how did they start?

In her trademark easy-to-follow narrative voice, this fact-filled picture book tells the story of the evolution of movies and the people who worked hard to create them—both on-screen and behind the scenes. In fascinating detail, she shows how early photography capturing motion became silent films, which led to the first color films and how those building blocks allowed for the inspiring movies of today.”

Sometimes a publisher or publicist reaches out to me about a feature on this blog. For this book? I’m the one who begged Meghan to let me interview her. You’ll see why soon enough.

Betsy Bird: Meghan, I can’t thank you enough for letting me pepper you with a plethora of questions. Because after reading ACTION!, I was just overflowing with them. This book consists of amazing scenes from classic works of cinema spanning pretty much the whole history of silent movies. The idea of having to pick and choose from the entirety of silent film history is daunting, to say the least. How did you decide what to include?

Meghan McCarthy: I watched hundreds and hundreds of movies and the more I watched the more daunting a task the creation of this book became. I remember complaining many times that I’d bitten off more than I could chew. But sometimes when I’m pushed to my limits I end up with the best product. After much thinking I decided to include the inventions and films that I thought contributed to and inspired future movies most (I do realize that is a very subjective decision). For example, even though I’m not a huge fan of Thomas Edison, he definitely deserved a place in the book and a prominent one. Without his ruthless business instincts, which created a very competitive environment, the advancement of movies may have taken a lot longer and perhaps California would never be the movie making mecca that it is today. Then take an actor such as Buster Keaton. His physicality really pushed the ball forward as far as what stunts could be done on film. Or take the actress Josephine Baker. What she did was quite bold for that time period and she proved that a black actress can have widespread appeal.

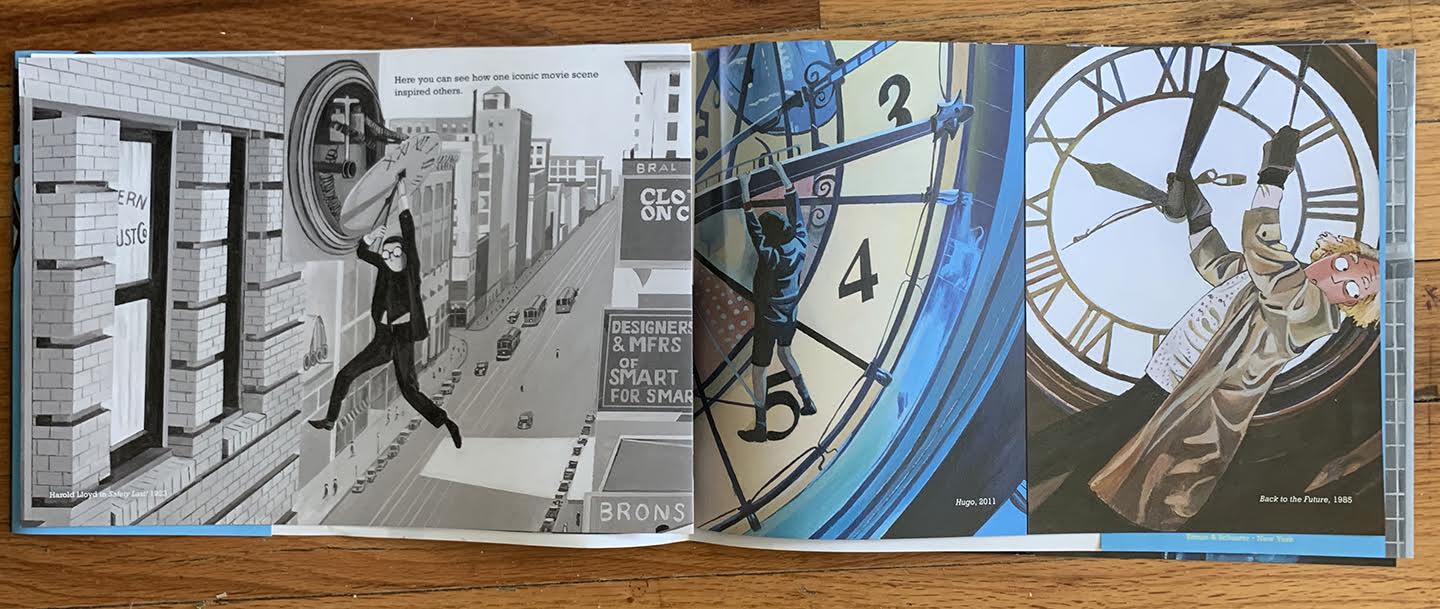

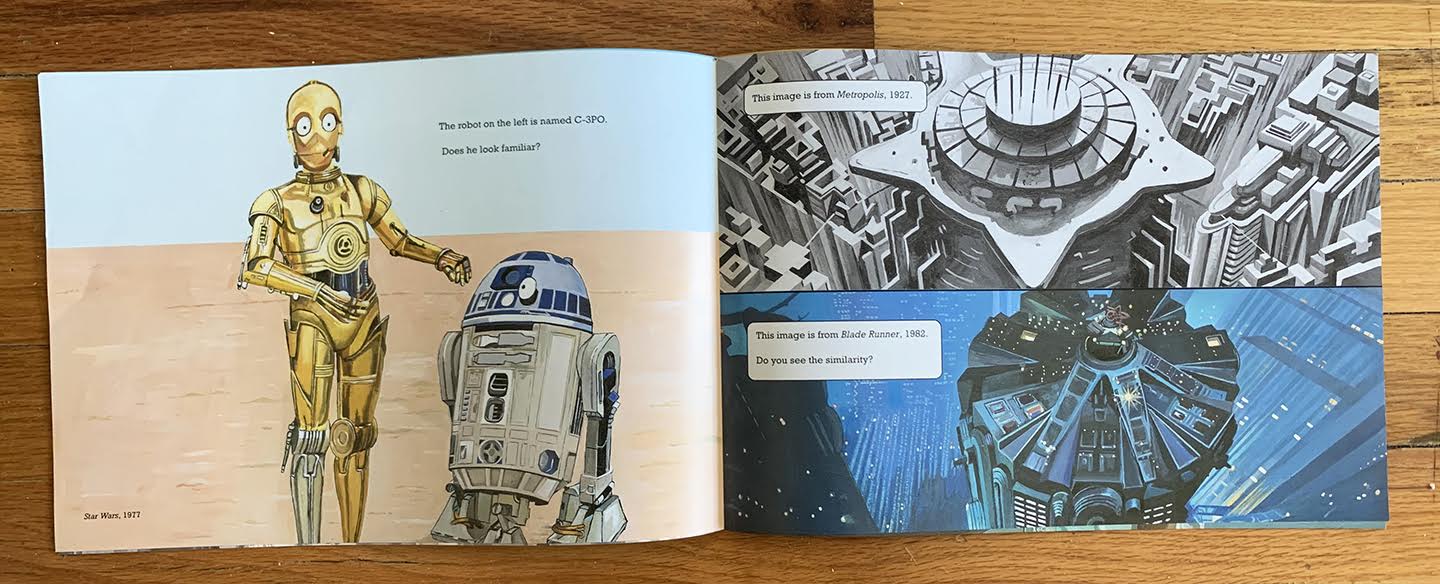

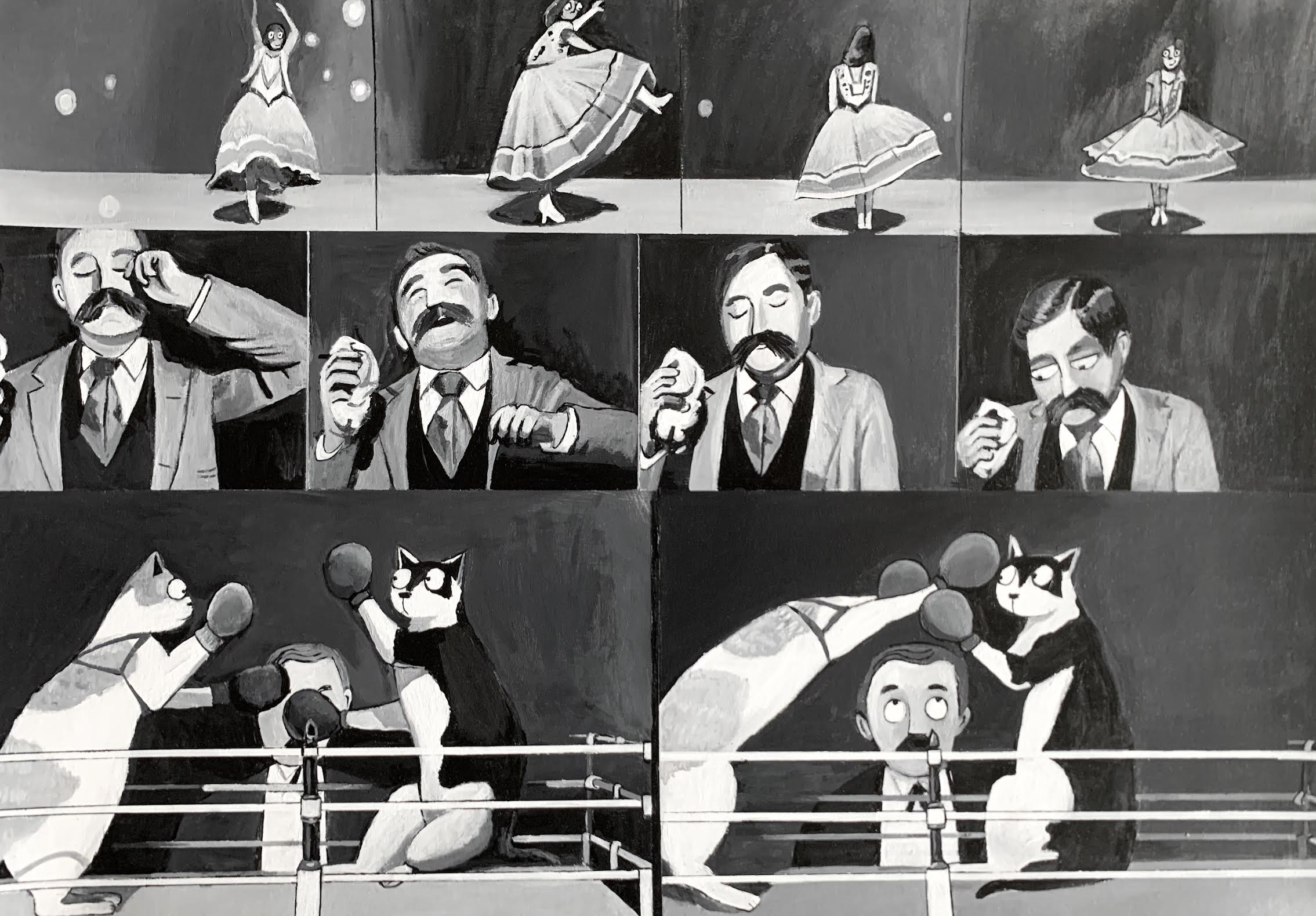

BB: What’s particularly impressive is that you make a lot of this relevant to kids today by tying in older films to new ones. So you’ll show Harold Lloyd hanging off a clock in one panel and then Hugo Cabret doing it in another. Or the automaton of Metropolis next to C-3PO. Can you talk a bit about these pairings and what you did with them?

MM: I’ve never made a book that doesn’t mostly contain one illustration per spread. The reason is that placing one image against another can be problematic. The colors of one can clash with the other so I rarely place competing images side-by-side. But Action allowed me to do something different. I was able to place black and white images next to color ones and instead of clashing they are complimentary. Of course, this meant that instead of creating twenty-four images I had to make more than forty-eight. This was double the work but worth it.

It is obvious that the film makers of today were directly inspired by the films many decades earlier. If you watch the opening sequence of Back to the Future, while the camera is panning across an array of ticking clocks, you will see a black and white photo of a guy hanging from a clock, who strongly resembles Harold Lloyd. The film is not only giving a nod to the 1923 film but it’s also an inside joke for film buffs. Jump to Scorsese’s Hugo, which is based on the great book by Brian Selznick. In the film the main characters go to the cinema and watch a Harold Lloyd film—Safety Last. Every bit of Hugo is an homage to the silent film era. So, illustrating those comparisons was a must.

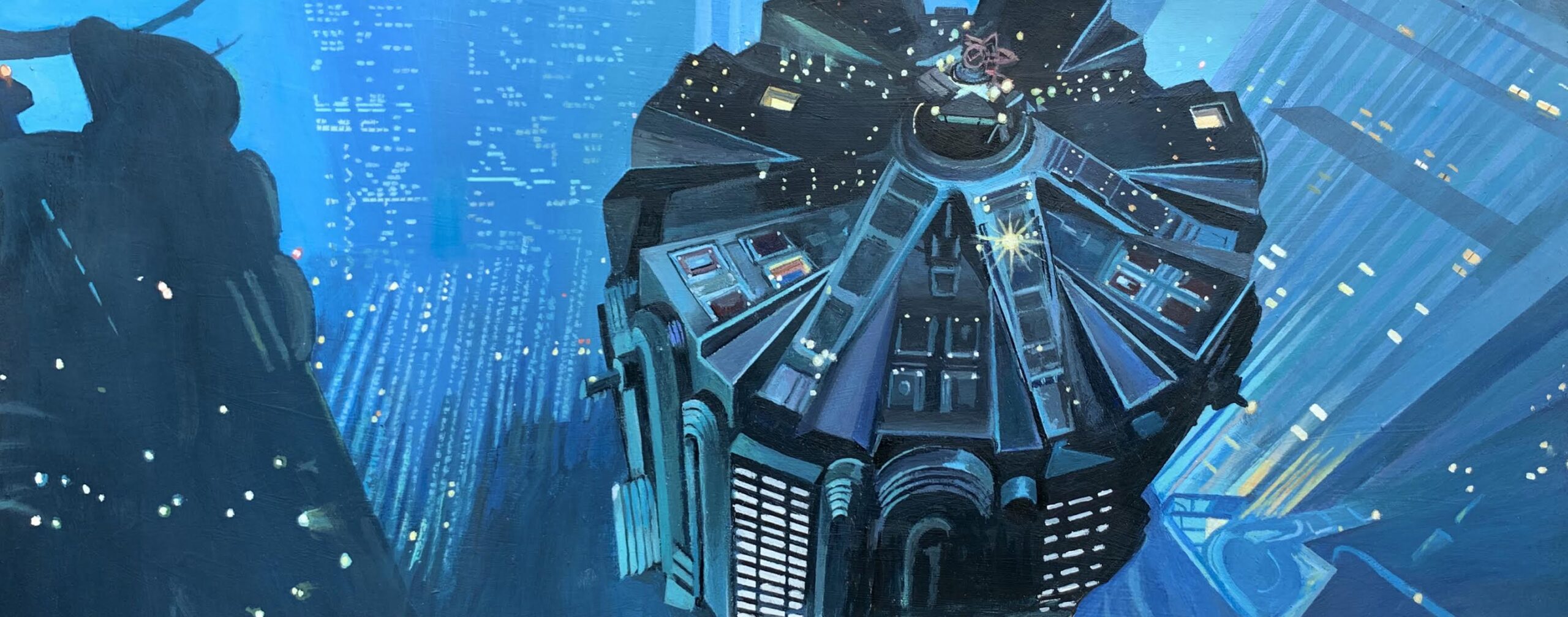

Another comparison is Star Wars and Metropolis. The minute I watched Metropolis and saw the robot, or Maschinenmensch (machine-human) as she was called, the lightbulb went off—ah, Star Wars.

There are other iconic movie scenes that I could have added, such as the scene from The Untouchables, when a baby in a carriage bounces down a set of stairs during a shootout, past whizzing bullets and gunshot victims strewn about. That is obviously a reference to the 1925 Russian film Battleship Potemkin. Due to limited space, I decided to avoid painting this one–that and the fact that it would have been considered, shall I say, slightly inappropriate for a children’s book.

BB: Ah well. So what else did you want to include and just couldn’t find a way to work it in?

MM: Just about everything I came across. I’m not exaggerating. That’s why this book was so hard to do. It was a daunting task and I’m lucky to have all of my hair after all the stress I brought upon myself. I made the decision to not rush things and to risk going bankrupt as a result. I was so tunnel visioned, so focused on “the art,” that I’d convinced myself that if I had to live in a cardboard box because the book took several years, and I earned no money and couldn’t pay my bills, then so be it.

There are genres that I could have included but didn’t, such as the swashbuckler film. It would have been fun to paint the Johnny Depp in Pirates of the Caribbean next to Errol Flynn in Captain Blood. The same goes for the comedic work of The Three Stooges next to any of our modern-day comedians like Jim Carrey. My thought behind leaving those topics out is that I thought they, in my opinion, were more prominent in later years. I also struggled with whether to include the genres of documentaries and sports. Since the book was so limited on pages, I decided to also leave those out as they are very different from fictional genres. As I will express later, it would be great to do a second book (or third or fourth!) on the topic of movies and include those genres.

BB: I wholeheartedly agree! In fact, I got to the end of this book and was furious that it didn’t continue. I could have read another 100 pages of it. So tell me about the backmatter. You’ve got these amazing stories involving early female film editors and plane crashes with lions back there. Was any of the backmatter slated for the book itself originally?

MM: For the main text, I included only inventions or movies that I think moved the ball forward as far as invention and innovation goes. Obviously, a film editor contributed to the process but didn’t necessarily alter our history of movies as we know them. But… I knew I had to put the story somewhere. The backmatter allowed me to quote quite a bit from the film editor Margaret Booth and I think her actual words are far better than me summarizing them. Back in my grandma’s generation, women didn’t often have careers so I found Booth’s story to be really inspiring. I was equally excited about the story of Leo the Lion. His existence didn’t necessarily move the progress of movies forward but the story is a great one and I had to put it somewhere. It wasn’t until I finished researching and writing that section that I realized Leo’s crazy story could be a picture book by itself. I suppose it’s never too late! I did originally mention movie-makeup in main text but it got tossed onto the cutting room floor. Lastly, poor Le Prince. If he didn’t go missing then perhaps he could have had Edison’s slot.

BB: What was your process when replicating some of these famous scenes? Some are incredibly meticulous, filled with tiny details, like the shots from Blade Runner and Metropolis and some a bit broader. Did you have a method that worked for you?

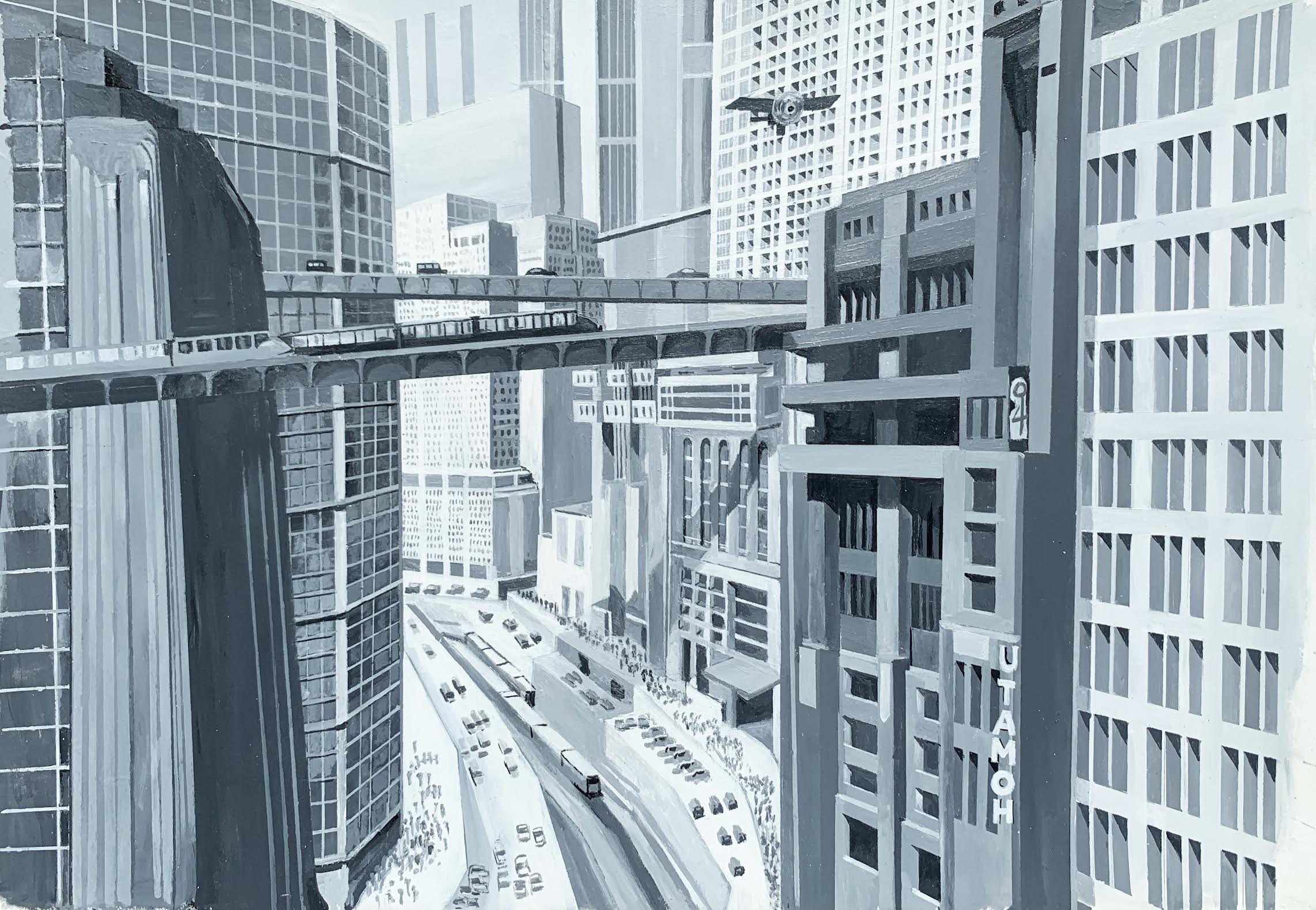

MM: Starting when I was in high school and moving into college, I painted a lot of realism. In fact, I had a teacher who strongly recommended that I pursue romance novel cover illustration because he said that not many people could pull off photorealism but that I could. It’s a good thing that I didn’t pursue that line of work because I’d be out of a job, as photographs are now most commonly used. None the less, I think I somewhat yearned to get back to realism. This book gave me an excuse to create more realistic paintings compared to many of my other books, although I think I was moving toward that with my last– book Firefighters’ Handbook. For some reason, I thoroughly enjoy the torture of recreating a scene like Blade Runner or Metropolis.

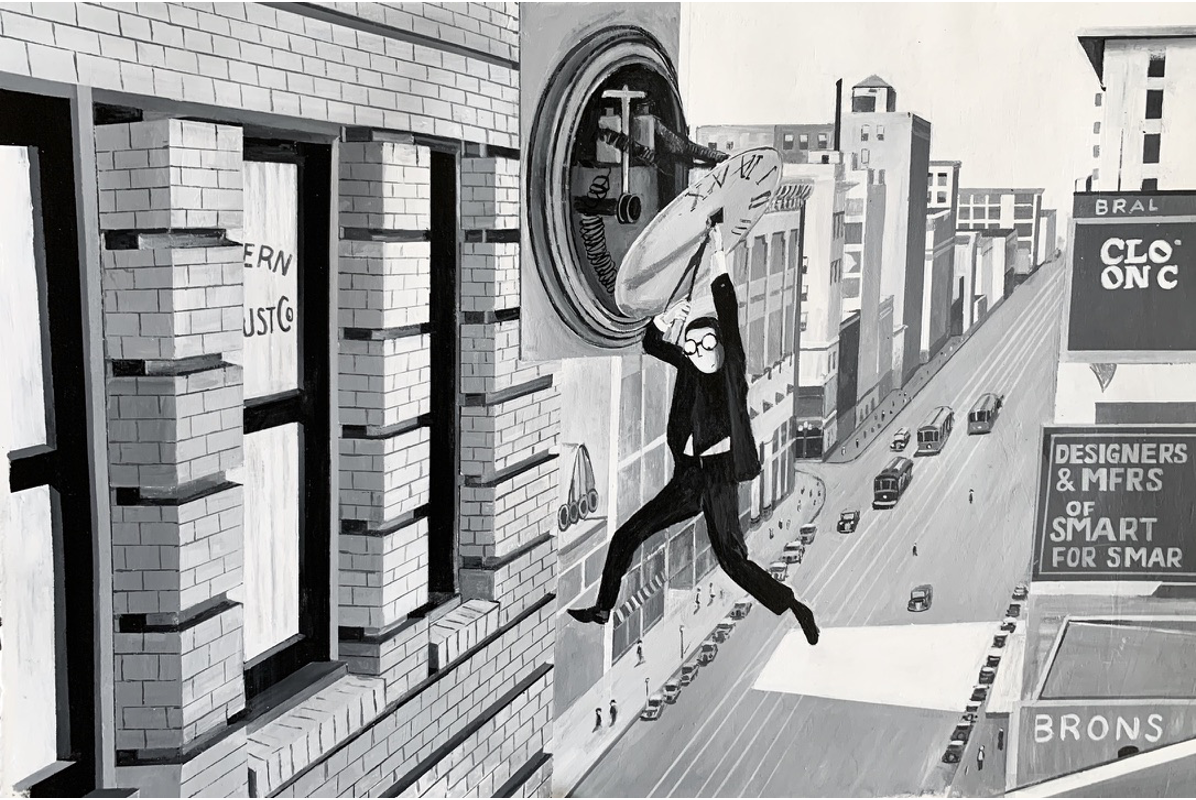

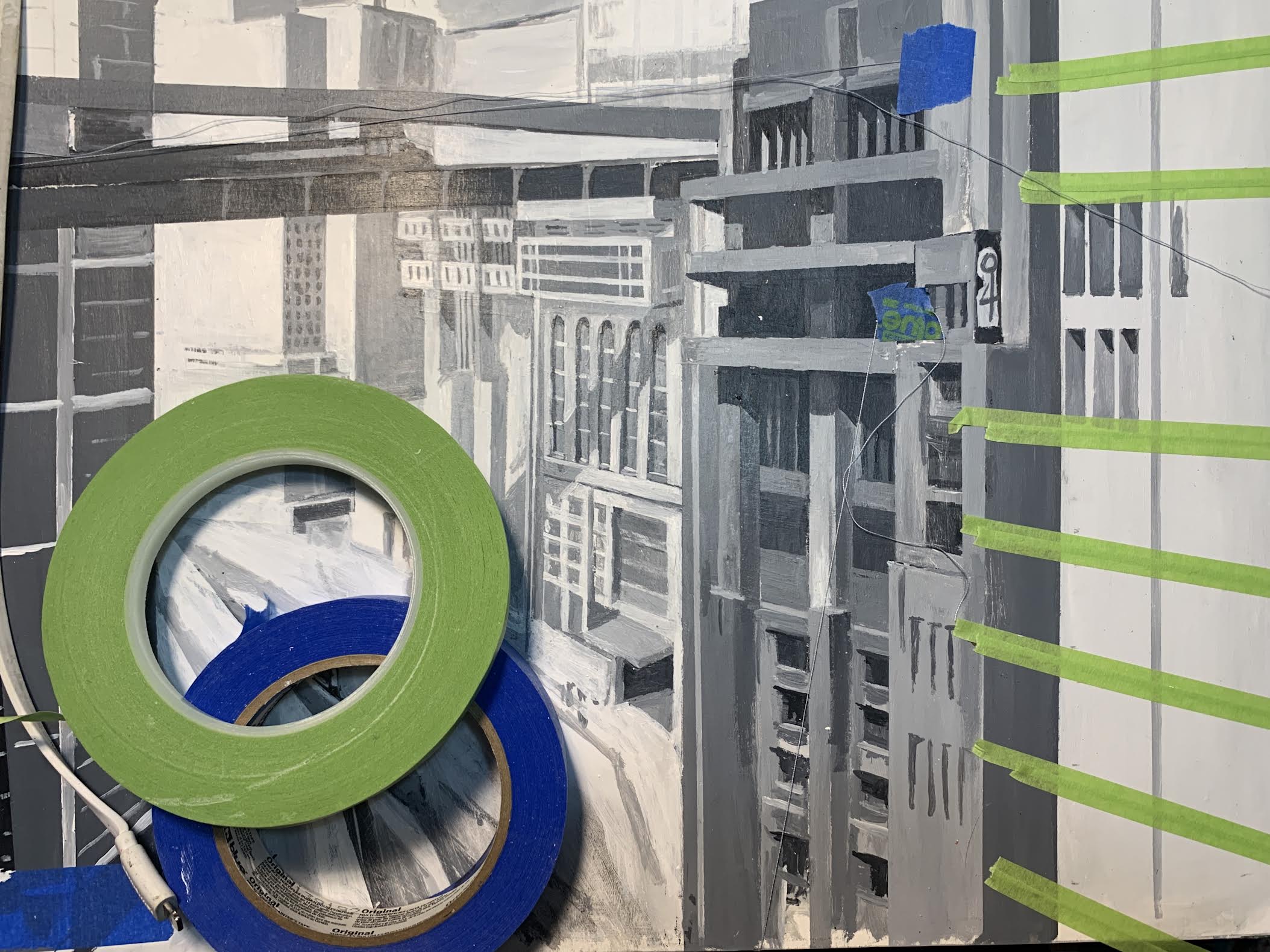

To get the perspective right, a trick I use a lot is to tape a string to where I want the vantage point to be. Then I line up all the buildings/lines with the string.

(The string seen in the middle was used to line up the dozens of lines in this piece and to make sure that they were all accurately going toward the vantage point)

Another trick to doing realistic buildings is painter’s tape. I used rolls and rolls of it to make those straight lines. I ended up with a ball of condensed and used sticky painters tape the size of a basketball. This tape did cause the paper to rip a lot so I often made repairs as I worked. Then I’d shout “Not again!” as I’d peel off the tape and watch the paper and a piece of the art go with it. Halfway through the book, I discovered automotive tape, which is thinner and it bends. It’s less sticky so it didn’t rip the paper. I will say that recreating Metropolis was a special challenge for me because the vantage points didn’t always line up—the scenes I copied were a tad wonky.

Also, believe it or not, most of my previous books’ art was started by me “sketching” with black acrylic on the actual piece and without looking too much at the sketch (I do this for my entertainment, so I’ll be surprised by the finish). The problem is that sometimes that black shows through when scanned so I worked a bit differently this time. I therefore sketched out the pieces with pencil instead.

A technique I used a few times, such as with the painting of this mountain, was to draw a grid over my photo reference (easy thanks to the ipad!).

For this painting I made a grid out of thread that I taped to the sides of the paper. There was no other way I could recreate all that detail because the brain can’t absorb all of those details at once. The painting is too daunting otherwise. It’s a trick photorealism painters like Chuck Close used back in the 60s and 70s—you focus on one square at a time.

BB: Another impressive aspect of the book is the use of color. We think of black and white films as so colorless, but you’ve found great way to work in shades of yellow into the scenes of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, or a spooky blue for Nosferatu. Did you ever consider making most of the book black and white or did you know you’d put in these shades at the start?

MM: I did consider a completely B&W book but my editor and art director really pushed for color. In fact, they wanted color on every page but I begged them to allow me to make a lot B&W or just two-toned scenes and they relented. I don’t think they knew just how colorful the dyed movie scenes would be until I turned in the final art. I thank my editor and art director for trusting me. I also thank them for pushing me to add more color because doing so gave me the idea to pair old films with new ones. I think the juxtaposition is exciting.

BB: It really turned out well. What turned out to be the most surprisingly difficult part of putting the book together?

MM: The whole thing from beginning to end. There were a lot of puzzles to be solved. This book took two and a half years and for good reason! It’s my pandemic baby. I think the biggest thing I struggled with was what to include. It was a monumental task.

BB: And now a slightly more ridiculous question. I knew about a lot of these early films like “Arrival of a Train” and “Baby’s Meal”. But I did NOT know about the 20 second film “The Boxing Cats”. Why has no one ever talked about the fact that cute cat videos were there at the very start of the cinematic process? And how did you hear about this?

MM: I have wanted to make a graphic novel about Edison vs. Tesla (the electricity war) for more than a decade so I’d read extensively about Edison and “his” inventions. The boxing cats were on my radar for many years. In fact, I used to show that film in my school presentations and kids always laughed hysterically. I therefore knew I had to include that one.

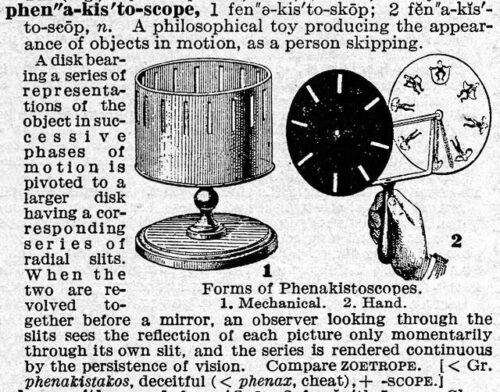

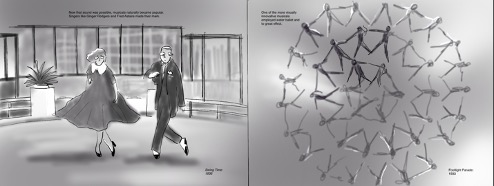

The funny thing I discovered while making this book is how old ideas seem to get recycled and repackaged into slightly different forms and then sold to us as something “original” and “modern.” I initially wanted to include this but made the decision to leave it out because it’s sort of a pre-film topic: The zeotrope, phenakistoscope, praxinoscope, thaumatrope—they operated slightly differently but essentially, they were a series of drawn images, that when spun, would appear to animate. There were goofy ones and serious ones and strange ones. They are the original GIFs! So are the 5-30 second 1800s films. It’s really funny to see how we moved to longer and longer media and then poof, the smartphone comes along and shortens our attention spans to that of what a kinetoscope would play.

BB: What’s your own favorite old film? And by “old” let’s say late-19th/early-20th century.

MM: I found The Kid, released in 1921 and starring Charlie Chaplin, to be surprisingly touching. It’s about a baby left on the street who Chaplin, playing a very poor beggar, despite having no child rearing skills, unorthodoxly raises. In one scene the kid breaks a window so that Chaplin can come along and offer his window repair services to the window’s owner. When I was in elementary school I wrote a story with that same exact plot–-the characters broke windows at night and then offered their repair services during the day. I remember thinking it was such a genius story idea. I didn’t realize that Chaplin had beat me to it!

If we move into the sound era a bit, an early sound film that really surprised me was Of Human Bondage (1934), starring Bette Davis (not child appropriate but is free on YouTube for your adult viewing pleasure). It was after viewing this movie that I realized just how much movies changed after the Hays Code, which was a list of rules movie makers had to follow so that their movies wouldn’t be obscene and corrupting to the viewing public, thus ushering in the screwball comedy. Bette Davis is a favorite of mine but her playing a woman who hopped from man-to-man, never satisfied, gave me a different view of the 1930s and women during that era.

BB: I know what a labor of love this book was for you but, I’m sorry, I just wanted more. Any chance you might follow it up with a book on the early talkies? Movie musicals? Please, miss, may we have some more?

MM: Hahaha. In my best fantasy, this would be a whole series. The original project I’d pitched ended with the advent of full color movies and I envisioned the last scene being from The Wizard of Oz. Unfortunately, the more I worked on the project, the more I realized that there was SO much to cover that I had to keep the book limited to the silent era so a good bit of what I’d sketched out had to be scrapped. But I’d love to cover movie history’s transition to full color, musicals making their debut, movie monsters, the screwball comedy (Bringing Up Baby anyone?), and so on. I could probably do ten books just on early movies.

(sketch for Wizard of Oz, spread on musicals, and my idea for a monster montage for the book that doesn’t yet exist)

BB: I wish you would. I really really wish you would.

Can’t get enough of process? I hear you. So why not check out this incredibly fun Time Lapse look at how Meghan painted this two-page spread of Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton. Good for what ails ya!

As you might imagine, I cannot thank Meghan McCarthy enough for taking this incredible amount of time not simply with her own book but with answering all of my questions SO thoroughly. As I mentioned before, ACTION!: HOW MOVIES BEGAN is on shelves everywhere August 23rd. Look for it then.

Filed under: Interviews

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Name That LEGO Book Cover! (#53)

K is in Trouble | Review

Fighting Public School Book Bans with the Civil Rights Act

Take Five: Middle Grade Anthologies and Short Story Collections

ADVERTISEMENT

Oo! Oo! Do Tesla/Edison, and then feature Steinmetz! The Steinmetz picture book is still waiting to be written!