The Big Bath House Interview: For “body-loving parents, rebel reviewers and vanguard author-librarians”

Think you’re for body positivity? Then it’s time to put your money where your mouth is.

Recently I’ve been enjoying the podcast You’re Wrong About, where the hosts interrogate some aspect of relatively recent history that we may remember incorrectly or not particularly well at all. Some of their best subject matter occurs when they talk about America’s “moral panics”. A moral panic constitutes “a feeling of fear spread among many people that some evil threatens the well-being of society”, or so sayeth Wikipedia. Moral panics occur, to a certain extent, in the field of children’s literature as well. There are topics and subjects that, when they occur in books for children, can potentially set off an instinctual, puritanical knee-jerk response. And in my experience, nothing exemplifies this better than nudity.

It’s no coincidence that the late great Maurice Sendak took a particular juvenile joy in books where kids just ran around in their altogether. In the Night Kitchen has probably had more academic articles discussing the significance of the “milk” in that book (because god forbid milk mean milk) than bears thinking about. And many is the children’s librarian that has discovered a book where “helpful” patrons have pasted, taped, or otherwise glued clothes onto nude figures. I remember opening a copy of Eric Carle’s Draw Me a Star where Adam and Eve were decked out in cute little halter tops of the notebook paper variety.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Generally speaking, most American publishers these days put the kibosh on any nudity in their books before they even start. And even if you get a book like this year’s Fred Gets Dressed, the genitalia is generally absent. It’s those pesky imports from other countries that usually stir up the trouble. I well remember an image from the original edition of Coco and the Little Black Dress by Annemarie van Haeringen where a woman gleefully throws off her corset in a joyous leap, baring her breasts to all the world. In the U.S. edition I believe that image was amended so that she wore a lose chemise instead (which kind of defeats the whole point of the page, but ah well). Very very few publishers are willing to risk potential censure. Maurice Sendak’s playfulness is now a thing of the past.

But that doesn’t mean that nudity is impossible. What if it could be presented in the spirit of the aforementioned body positivity? What if it was placed in cultural context and shown to be natural and not something to be ashamed of?

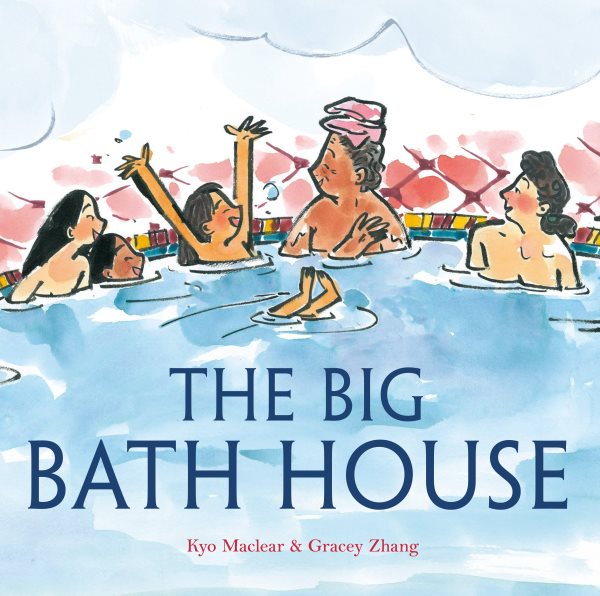

When I first saw The Big Bath House by Kyo Maclear, illustrated by Gracey Zhang I instantly adored it. The title envelopes you in this warm, caring family in Japan. Was this an international translation? But, no. We’ve seen Kyo Maclear’s books for years (my personal favorites of hers being It Began With a Page and The Liszts). She’s coming out of Canada, for crying out loud. And yet here, released on November 16th of this year, is a book that dares to tell a loving story about women going to the bath house to get clean together. From the publisher:

A joyful celebration of Japanese cultural traditions and body positivity as a young girl visits a bath house with her grandmother and aunties

You’ll walk down the street / Your aunties sounding like clip-clopping horses / geta-geta-geta / in their wooden sandals / Until you arrive… / At the bath house / The big bath house.

In this celebration of Japanese culture and family and naked bodies of all shapes and sizes, join a little girl–along with her aunties and grandmother–at a traditional bath house. Once there, the rituals leading up to the baths begin: hair washing, back scrubbing, and, finally, the wood barrel drumroll. Until, at last, it’s time, and they ease their bodies–their creased bodies, newly sprouting bodies, saggy, jiggly bodies–into the bath. Ahhhhhh!

With a lyrical text and gorgeous illustrations, this picture book is based on Kyo Maclear’s loving memories of childhood visits to Japan, and is an ode to the ties that bind generations of women together.

I had to know more.

Betsy Bird: Kyo and Gracey, thank you so much for joining me here today! I have so much to ask. Kyo, let’s begin with you. Tell us a little about the origins of this book. To start us off, where did it originate? I know that in your Author’s Note you mention that you used to take a similar trip to the bath house with your own grandmother. Can you tell us a bit more about that?

Kyo Maclear: Growing up, I spent every summer in Japan with my mother’s family. Visiting the bath house, or “sento,” was an anchoring ritual. The bath house was where we’d mark a year’s worth of changes. My aunties would touch their tummies—bigger now. They’d run their fingers through my mother’s hair—more gray. They’d pat my cheeks—a teenager soon.

At the bath house, I was introduced to this rare, beautiful world where women’s bodies were simply noted and accepted. It was only when I became an adult that I realized how radical this is; to grow up around bodies of every shape and size, when every scar and stretch mark can be seen; to just linger in a place where people of all ages soak up each other’s physical presence.

When I look back on my childhood and what gave me my backbone, I immediately think of my obachan (grandma), my mum, my aunties, and these bathing women. This matriarchy gave me my confidence and a sense of self that couldn’t be eroded when I returned to North America.

I’d never seen this bath house experience represented and I wanted to share it with readers and also remember the close connection I had with my obachan despite our language limits.

BB: Gracey, how did Kyo’s manuscript first come to you? What were your first thoughts?

Gracey Zhang: I was sent Kyo’s manuscript by my agent and I loved and resonated with the story immensely. It reflected and brought back so many memories of how different nudity was treated by different cultures growing up for me. I grew up in Canada and we had many Asian communities in our neighbourhood. I spent a lot of my time at the local pool and it was always a familiar sight to see older Asian aunties in the pool and the shower rooms. There was no shame in nudity for them—their race in conjunction with their nudity was pointed out by my classmates and peers, I remember feeling embarrassed from their lack of modesty in the changing rooms. Now a little older, I welcome the openness and hope that our/all bodies can be seen without shame and judgement.

BB: There are certain key differences between picture books originally published in America and those published overseas. One of the biggest is the role of nudity in these books. Americans are typically very squeamish about this kind of representation. When writing this book, how important was it to show the bath house honestly, as it would appear to someone attending?

KM: I realize there are different sensibilities but this squeamishness just doesn’t fit with my experience. As you say, there are picture books outside North America that freely embrace (incidental, nonsexual) nudity. There are books that say breasts and bottoms are normal and amazing! For example, I think of Tarō Gomi or Genichiro Yagyu where a candour about the body is standard fare. Like Gomi and Yagyu, I simply started from this baseline of everyday body acceptance, which is how I was raised.

So, yes, I definitely wanted to show the bath house honestly but I didn’t want to write an explain-y book. I didn’t want a sociological voice that made the bath house, or nudity, seem unusual or, ugh, exotic. I chose the second-person voice so I could speak directly to the reader and right away bring them in as a participant rather than a voyeur. The story plunges the reader into the bath house, without explanation. I didn’t set out to cause sparks. I set out to normalize body positivity but also, and maybe more importantly, to celebrate communal spaces, a certain amazing attitude towards elders, and the experience of an intergenerational bond that goes beyond words.

BB: Gracey, when looking at the bodies featured in this book, I was reminded of Robie H. Harris’s great title IT’S PERFECTLY NORMAL, illustrated by Michael Emberley. Much like this book, that one talks, and shows, the wide range of bodies, “imperfections” and all. You do a great job of showing all kinds of women’s bodies, young and old, large and small. Was that important to you to include?

GZ: Yes! Our bodies do and carry so much of our burdens. They see us through our lives. Bathhouses are a place to relax, soothe, heal those bodies, in honouring that work—a reflection of the old, young, in between bodies is the least I felt I could do.

BB: And Kyo, when you first saw Gracey’s art, what was your initial impression? Was this how you’d envisioned the book or did it take the information at a different slant?

KM: The goal I think for Gracey and me was to create a book where the words and images were in emotional sync. I’m very grateful to our excellent editor, Annie Kelly, for pairing us up. As soon as I saw Gracey’s sketches, I knew we were on the same wavelength. There’s an energy to her line that’s full of flow and disinhibition and that felt exactly right. I was happy/relieved that Gracey had zero hesitancy about including jiggly bottoms, saggy breasts and a spectrum of body types. And I loved the way she placed the main character firmly at the center of a community, shifting the storytelling emphasis from individualism to collectivism. The overall feeling is just one of communal joy and familial tending, which feels particularly powerful and poignant in the wake of the past year of anti-Asian violence. We need more stories of Asian female joy. I mean, just look at how lovingly Gracey conveys our care for each other.

BB: Gracey, did the final version of the book match what you’d initially envisioned it to be? Did anything get cut, removed, or changed along the way?

GZ: I was extremely fortunate to be working with an editor and art director, Annie and Rachael who believed in Kyo’s mission as much as I did. I received some proofs of the artwork a bit ago and am so excited to see it come together. All the artwork seen was made as it appears.

BB: And have you ever visited a Japanese bath house yourself? Did you have to conduct a certain amount of research to get it right?

GZ: Funnily enough—yes! My mother is from Taiwan but she attended Hosei Univeristy in Tokyo and spent her early career there. She often travelled from Canada to Japan when I was young, which included a memorable trip to a bathhouse. I received some great photos from Kyo of her own childhood at the bathhouses, I had done some research online for references but also found myself checking with my mother as well.

BB: Kyo, any book published in the States for children that contains nudity of any sort is going to meet with challenges. So much of what I like about this book is that it’s coinciding with new conversations about how we view bodies and what we say about them. I like to think that this book is part of a larger movement that fights against body shaming. Still, how are you preparing for the backlash?

KM: A few thoughts come to mind. First: my matriarchs always taught me to be comfortable in my own skin. This was the unspoken wisdom of the bath house. So, I am trying to channel that confidence. Secondly: I generally think writers, especially BIPOC writers, need to spend less time in the minds of imagined ‘normative’ readers. My lodestars have always been writers such as Toni Morrison and Maxine Hong Kingston, neither of whom ever diluted their stories or altered the perspective or language to make those stories more palatable to an imagined norm. When you take this approach, you create a story where the characters are just living and relating, where everyone else outside that experience gets to eavesdrop. You might open yourself up for criticism but you also, with time, help shift the gaze. Thirdly: maybe I’m foolishly trusting—and you certainly know far more than I do about the American publishing world—but I generally expect readers to come to a book with a spirit of openness and curiosity rather than from a place of grouchy cultural conservatism. Sometimes this sense of faith blows up in my face. Sometimes I experience push back. But sometimes, often even, there is a nice bonding experience that happens when I cross perceived lines of ‘appropriateness.’ It turns out readers want to cross lines too. It turns out, at least in my experience, young children are willing to go anywhere. They’re not the ones with the hang-ups. My final thought: If there is push back, I’m hoping our book will be protected by good, gentle, generous readings and shared by body-loving parents, rebel reviewers and vanguard author-librarians.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

BB: I love so much of what you’ve just said here. And I hope it’s clear how much I love this book. I desperately want it to find as much of an audience as possible. My hope is that people will come to it precisely, as you’ve said, with “openness and curiosity”. And so, I ask the both of you, once and for all, what are you working on next?

KM: I’ve been working on caring for my mum who has Alzheimer’s, trying to cultivate some serenity of focus, and slowly writing a new book for adults about plant life and family secrets.

GZ: I have a few more books I’ve been excitedly illustrating for that should be out in 2022! There are also some more projects underway that will be out a little later 🙂

To Random House Studio, who is publishing this book, editor Ann Kelley, Kyo Maclear, and Gracey Zhang, I thank you. The Big Bath House is on shelves November 16th. And I cannot wait for you to see it.

Filed under: Best Books, Best Books of 2021, Interviews

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

One Star Review, Guess Who? (#202)

More Geronimo Stilton Graphic Novels Coming from Papercutz | News

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

Environmental Mystery for Middle Grade Readers, a guest post by Rae Chalmers

ADVERTISEMENT

I love, love, love “You’re Wrong About”! And as a self-proclaimed rebel-vanguard-librarian, I just added the book to my To Be Ordered cart. Is it November yet?