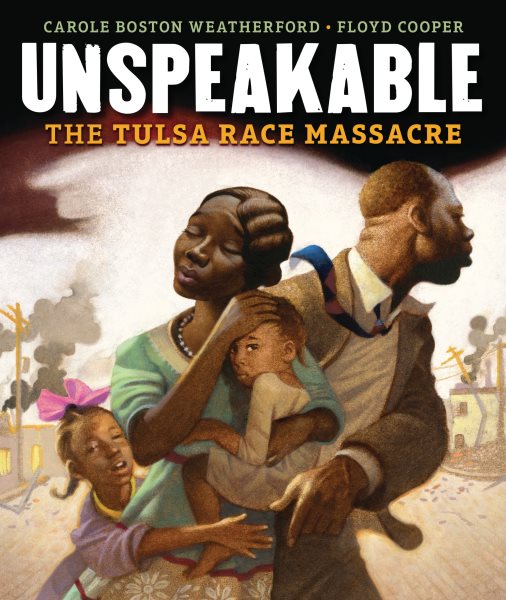

An Unspeakable Interview: Talking with Carole Boston Weatherford & Floyd Cooper About the Tulsa Race Massacre

When I tell you that there is an informational picture book out this year on the topic of the Tulsa Race Massacre, how do you react? Are you incredulous or do you nod slowly? Are you curious or do you try to guess how it could be done? Carole Boston Weatherford has been writing for children for years and years and years. Her books have an incredible tendency to win major awards (Freedom in Congo Square, Voice of Freedom: Fannie Lou Hamer, Becoming Billie Holiday, etc.), to tell stories of people that have never appeared on the pages of picture books before (Schomburg, The Roots of Rap, Racing Against the Odds: The Story of Wendell Scott, etc.), and, on occasion, to dip into fictional territory too. It is impossible to overstate the influence she has had on the field of children’s literature to date. Who better to discuss the impossible with children?

Floyd Cooper, meanwhile, may give Carole a run for her money, should we try to keep track of who has been making children’s books the longest. His books have given equal weight to fact and fiction, truth and imagination. When it comes to illustrations, his leave indelible images.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

I was given the chance to ask Carole and Floyd about their latest title Unspeakable. I took the opportunity I was given:

Betsy Bird: Carole, we’re talking about the Tulsa Race Massacre, a.k.a. the worst racial attack in history, with this book. One that a lot of people were unaware of prior to 2020. I know that there are people saying that this would be an impossible topic to cover in a book for children. Yet you and Floyd must have been working on this book long before Tulsa became national news. How did you come to this story and the decision to make it accessible to kids?

Carole Boston Weatherford: So African American history has been lost, omitted, or twisted. State and local officials deliberately covered up the Tulsa Race Massacre. Until recently, it wasn’t even studied in Oklahoma schools. I heard about the massacre decades ago, and I decided a few years ago to tackle the subject. If children of the past were—and still are—victimized by racial hatred, then today’s children can learn about it. I do not think that young readers are too tender for tough topics.

BB: Floyd, you have a personal family connection to this story. When you were tapped to work on this book was that known to Carole or your publisher? Can you tell us a bit about your grandfather?

Floyd Cooper: I do not think Carole Boston Weatherford or Lerner knew before they initially considered this project just how personal the narrative is to me. I believe I informed Carole somewhat early on when we began our discussions of possibly working together on it. (She approached me about illustrating even before submitting the manuscript to a publisher.) I am not certain when Carol Hinz, our editor at Lerner, became aware. I must say that it was a sweet coincidence at best that the stories my grandpa told to my cousins and me would someday become a picture book the likes of Unspeakable and published by Lerner!

My grandpa C.D. Williams gave us so much in the way of what came before us and before him and on and on. For one thing, he loved to talk—but then, we loved to listen!

I remember being sooo fascinated with the stories of his youth. I was one of those kids with a big imagination, and his stories played out in my head like an IMAX movie. One of his stories was about the burning of Black Wall Street, Greenwood Avenue, Tulsa, Oklahoma, in 1921. And he was there, a live witness to it all.

BB: Carole, the sheer amount of research you must have conducted for this book is evident on every page. The text is at times a catalog of the Black businesses and doctors and shops and stores in Tulsa. What kinds of sources did you consider? How did you even go about beginning to research this? As you mention at the end of the book, so much of this history was deliberately covered up. How did you get around that?

CBW: Thanks to data research by the Oklahoma Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921, the Oklahoma and Tulsa historical societies and the Greenwood Cultural Association, I was able to reconstruct the landscape and events of 1921. The Commission, which was authorized by the Oklahoma state legislature in 1997, made a concerted effort to document the massacre and to fill the void created by the cover up. One outcome of the commission’s study was semantic. The incident, at first termed a “riot,” is now more aptly called a “massacre.”

BB: If I could draw a clear cut line in the sand between the books that came out when I was a kid and the books coming out today, one of the biggest (and perhaps least remarked upon) differences may be how we frame history for our kids. When I was young, history was taught as a slow, steady walk towards progress with no backtracking. It was as if adults didn’t dare show kids that things could get better then worse again. Do you feel like there’s a shift in how we teach our children history these days? Can you speak to why this is changing?

FC: I certainly would hope so. I believe if we step back and examine where we are now compared to where we once were, we would see the growth of America. On many levels we can bear witness to the fact that our nation is not static, is not locked into a single perspective when it comes to anything really—and that includes our understanding of history and the passing on of that history. I personally link the pervasive assault on truth that we see in our politics and media directly to historical truths that exist and have existed and are now being brought to light. A good thing for America. And of course there will be many who are and were just fine with leaving truth under the rug where it is had been swept for far too long.

Eventually, truth will always out. That is different from what it once was. With such a change comes resistance to that change, an unwillingness to accept the change, to accept the truth. That can lead to uncomfortable times. But there is a better day on the other side of change. After the wounds have healed, a much better day awaits! Our young will live in better times together in acceptance of the way things really are if we give them the truth. But we must teach them truth in ways they can comprehend. There is no greater gift than truth.

BB: Carole, there are a fair number of terms in this book that exist on the page without definition. At one point thirty Black men rush to the jail to save a man from being “lynched”. This brings to mind the audience. Do you see the readership of this book younger kids that will have these terms defined for them, older kids that may know them, or a mix?

CBW: I do not think that young readers are too tender for tough topics. Even before “anti-racist” was a term, my books highlighted social justice issues and engaged students in critical literacy. I document past atrocities like the Tulsa Race Massacre and the bombing of Sixteenth Street Baptist Church (in my book Birmingham, 1963) to introduce these injustices to young readers. I hope that children and adults will read and discuss Unspeakable together. Our response to such atrocities must never be silence.

BB: Floyd, I want to talk a bit about what you’re doing with the art in this book. There’s this shot early on when the book is discussing the community of Greenwood Avenue and how it was made up of people fleeing the segregated South. There are two little girls looking dead straight at the reader and they are not smiling. In fact the older sister has her arm protectively around the younger child and there are full-length novels you could read in her expression. And there are other moments in the book too where the page’s characters are looking right at you, and they’re considering you with great seriousness. I don’t think I’ve ever seen you do anything like this in a book before. What was the impetus?

FC: I appreciate your sensitive observation. The art in this book came from my heart. I painted each scene from a personal point of reference. How I remember the setting and details like the brick streets and buildings that still remained a part of Tulsa in my childhood. How I remember reacting when my elders told me these stories. And I guess some of that came out in my art.

BB: Carole, one of the things I love about how you’ve written the text is how you tie it into our current movements. You write about Tulsa’s Reconciliation Park, “the park is not just a bronze monument to the past. It is a place to recognize the responsibility we all have to reject hatred and violence and to instead choose hope.” What do you hope for with this book?

CBW: I hope that this book will connect the events of the past to persistent problems like racial profiling and police brutality. As a mother and grandmother, I want to help raise children who are anti-racist.

BB: Floyd, how you handle violence in this book can serve as a guide for other illustrators tackling tough subjects. In a moment when thirty Black men faced off against two thousand white men, you have a two-page spread of a Black man on the left-hand page raising his hand in a stop gesture as two white men on the right-hand page exist behind it. Later the mob violence shows the Black citizens running. Not what they’re running from. This, in many ways, may be what so many people wouldn’t know how to illustrate. When you have a massacre to depict, how do you tackle it? What are you thinking when you come up with these images?

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

FC: I think that there has been so much depicted in movies and the media that the illustrator really doesn’t have to graphically render as much of this in the visual narrative. Instead, I allow the “filling in of the blanks” as the story moves forward. One could argue that doing this would be somewhat like censoring history, not showing certain acts or scenes. But I would push back on that. We must use a little common sense when telling the truth to the young.

BB: And finally, what are you working on next?

CBW: I have picture book biographies forthcoming about Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi and the late congressman Elijah Cummings. Both lawmakers were born and raised in my hometown of Baltimore.

FC: I am currently finishing up a companion picture book to Where’s Rodney?, my collaboration with the amazing Carmen Bogan about a little boy of color who finds that where he thrives best is outdoors immersed in nature. Critical affirmation of Where’s Rodney? was in the fact that it was surprisingly rare to see a picture book about a child of color in the outdoors. The new book is titled Tasha’s Voice, and it’s about a girl named Tasha who finds her voice outside in a park. The publisher is the Yosemite Conservancy.

But why rely on mere writing? Hear the creators in their own words!

Hear Carole discuss this book in this video on its creation:

Check out this look at the interiors with additional thoughts at Seven Impossible Things Before Breakfast.

Read an additional Q&A with Carole at the Lerner site.

Take a look at an amazing discussion guide available for Unspeakable. The guide was written by Dr. Sonja Cherry-Paul who also created the educator’s guide for Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You.

Thank you to Carole and Floyd for taking the time to answer my questions, and thank you too to Lindsay Matvick and Carol Hinz for setting it all up.

This book will be on shelves everywhere February 2nd.

Filed under: Interviews

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

The 2024 Ninja Report: Bleak

Review| Agents of S.U.I.T. 2

Navigating the High School and Academic Library Policy Landscape Around Dual Enrollment Students

Read Rec Rachel: New YA May 2024

ADVERTISEMENT

Terrific blog and I absolutely cannot wait for this book! It seems like one of those projects that was just meant to be. I went through the day thinking about the illustration of the sisters. Thanks for including the videos with CC.

Thank you for this interview with these two great talents. I can not wait to see this book.

Thank you so much for these insights and telling this story, Carole and Floyd. Thank you for the thought-provoking interview, Betsy!