Review of the Day: The Talk, edited by Wade Hudson and Cheryl Willis Hudson

The Talk: Conversations About Race, Love & Truth

Edited by Wade Hudson & Cheryl Willis Hudson

Crown Books for Young Readers (an imprint of Random House)

$16.99

ISBN: 9780593121610

Ages 10 and up

On shelves now

What are we teaching our children? Or, put another way, what are we allowing other people to teach our children? If you live in the year 2020 then you are living through history. And history, like it or not, isn’t boring. But the business of publishing books for children is a slow process. The titles that we are seeing on our bookstore shelves right now have usually been in the works for years and years. Pre-COVID, at the very least. When you want to use the current cultural moment as a springboard, it can be difficult to do so when looking at the current crop of books for kids out there. But racism, in all its myriad forms, isn’t trendy. It isn’t something dreamed up in 2020. It’s longstanding, systematic, and baked into the foundation of our society. When George Floyd and Breonna Taylor were murdered and the country erupted into nationwide protests, lots of people started buying books that would help them understand the current cultural moment. Books like How to Be an Antiracist and So You Want to Talk About Race and Caste continue to fly off the shelves. But what about the children of those people? If you want to talk to your children seriously about race in this country, where do you begin? If they’re on the younger side of things you might hand them Not My Idea: A Book About Whiteness by Anastasia Higginbotham, but older kids need more sophisticated content. And to be perfectly frank, I’ve seen few books that tap into that desire to know more than The Talk: Conversations About Race, Love & Truth. Pitch perfect in tone and content, this is supposedly the book that will help all parents talk to their kids. In truth? This also is the book that will help kids talk to their parents. It’s a two-way street and everybody’s driving.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Thirty authors and illustrators. “There are many reasons why parents and caregivers share ‘The Talk’ with children,” write editors Wade and Cheryl Willis Hudson in the Foreword. And so, with the help of those thirty people, the Hudsons have compiled together a book that looks at different kinds of talks people have with their kids. Some are discussions of why the children must never despair, living in America today. Others prepare their offspring for danger, physically and emotionally. There are talks about why the offhand comment from that stranger you met the other day is NOT okay. Talks about what our ancestors left us. And if these have a common thread or through line, it comes from knowing that the words in this book, the advice it gives, aren’t just for the children of the creators. We aren’t all authors. We don’t all have the words to say what needs to be said to our children. Take comfort then in relying upon the experts. What they have to say, we all need to hear.

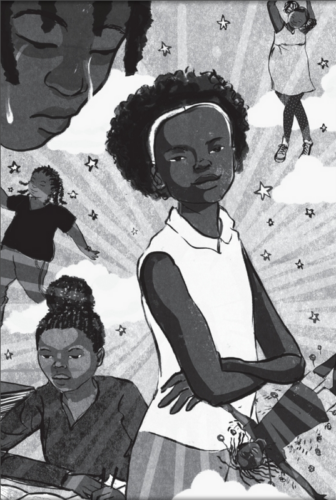

I flip through this book and think about how a kid would read through it. No book has just one use, after all. A book of essays, like this one, certainly CAN be read cover to cover, but let’s be realistic about how this book is going to get into the hands of kids and what it’s going to do once it’s there. If I’m a kid and someone put this book into my hands with very little context (which you know will happen when it ends up being assigned without much discussion or explanation) the first thing I’m going to do is flip through it. And since I’m the kind of person that likes everything to go in my order, rather than the intended one, I start at the back. So I start to flip and practically the first thing at the back that catches my eye is a great big image of a minotaur. That would be part of the essay “Mazes” by Christopher Myers (and one of my favorite pieces in the book). There isn’t much in the way of comics in the book, aside from a one pager by Natacha Bustos and one by Zeke Pena. And the images that are in the book are all black and white, but the design is strong. It changes style and none of the essays are ever too long. It’s the kind of book you can dip in and out of without much difficulty, and for all that its cover looks deadly serious (and starkly beautiful) there’s a lot of light and life and joy inside. But yeah, the likelihood is that a kid will be handed it, rather than think to seek it out themselves, is high.

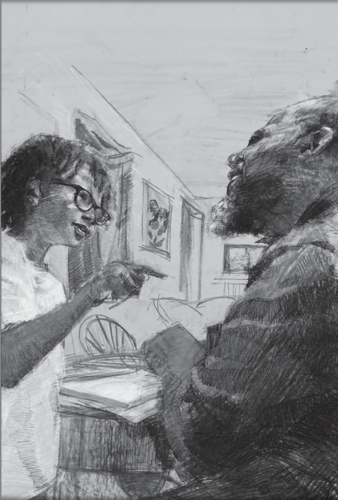

The essays themselves? Well, as with any collection they’re going to vary in quality. I know not what magic the Hudson’s yielded to get people to submit. The roster of contributors is a veritable who’s who of big names in the field. Still, I was wary going into it. Sometimes when I read a collection I’ll get the feeling that some of the creators just tossed off their submissions. That is not the case here. Here, even when I feel that a piece doesn’t hit as hard as its fellows, it’s still thoughtful, considered, and you can see the intentional hand of the author. Generally speaking, I found the pieces that were just letters to children to be less interesting than the ones that engaged actively with the material. When authors would pluck real world moments from their lives, or the lives of their children, and work them into their pieces, that was key. I’m not allowed to have favorites, and I know that, but Tracey Baptiste’s “Ten” in which she calmly and carefully enumerates to her son the ten rules on being pulled over by the police when you are Black, is thick with tension. I love how it’s accompanied by a piece of art by April Harrison. In a more just world, this book would have been full color. As it is, you come to admire where the art arrives and who is paired together. The balance between different types of pieces and illustrations also lets me admire the editors’ work as well. The Hudsons have crafted this book in the only order it could really have gone.

We all have our prejudices. Here’s one of mine. When I was flipping through the list of authors and illustrators featured in this book, I found myself nodding along at the long litany of names. Derrick Barnes, yep. Selina Alko, of course. Torrey Maldonado, absolutely. Adam . . . Gidwitz? A little bit of a pause on that one. Granted, I’ve heard Gidwitz begin talks with land acknowledgment statements. Plus his Unicorn Rescue Society books make a point of bringing in BIPOC authors when appropriate. Still, he felt like the odd apple out. Why was he in this book? Only when I read it did that I realize that as a white parent, it was Gidwitz’s story that kicked me hard and fast in the gut. While other essays in this collection are memoirs or stories or poems, Gidwitz’s is about white privilege. It doesn’t go all out and say that, of course. Instead, the title of his piece is the chilling title “Our Inheritance”. Chilling, I say, once you read the piece. In it, Gidwitz and his daughter talk about racism. She’s white, in fourth grade, and certain that she doesn’t know any racists. Gidwitz counters this with a story about her great-great-grandfather who was Jewish and arrived in Mississippi. As I read this story, I initially felt disappointed. The story of Papa Jake and how he pulled himself up by his bootstraps felt so reductive and overly familiar. The happy family story we white people tell one another and our children, with the significant gaps glided over. But Gidwitz isn’t playing around. In time, it became very clear that this wasn’t the usual Manifest Destiny tale.

He points out the fact that even Papa Jake had privileges in late-19th century America. He notes that their current comfortable financial situation comes from the company he founded. And then Gidwitz points out that the man made much of his money from sharecropping and kicked his customers off their land when they owed him too much money. And so the money that Gidwitz and his daughter benefit from, is money built on the backs of people enslaved, essentially, to their ancestor. And THAT is the inheritance we white people reckon with. And that is why after I read that story I sought out my own fourth grade daughter and told her the story of our family, and the immigrant from Norway, her Great-great-great grandfather who started a bakery in Oklahoma on land stolen from Indigenous populations. Because when we hear about The Talk that is given to kids of races that aren’t white, we white people forget that we have our own “Talks” that we should be giving. And thanks to this book, we can get a little push in the right direction by its example.

Is it for kids or for adults? I fielded that question the other day. I believe my answer was, “Yep.” So much of its success is going to rely on how it’s used. I can think of teachers assigning one story per day to a class. A parent reading a piece a night and then talking with their child. There will be the occasional older reader, maybe in middle school or high school, who operate on a lower reading level but wants something “real” that doesn’t talk down to them. Or the younger kid that’s so desperate to join the world of older kids and adults that they’re trying to read everything they can on racism so that they can understand everything better than the adults that surround them. To be an author is to put words out into the universe and never know how they’re going to perceived, appreciated, considered, or contextualized. The authors or illustrators in this book will not meet the bulk of their readers. And the Hudsons themselves don’t know, once this book is available for purchase in the real world, what its impact might be. I used to think I had a hard time with purposeful books, but now I know that’s not quite right. I have a hard time with poorly made purposeful books. Books like The Talk, however, are right up my alley. Release it into the world yourself and see what it does. Odds are, it’ll do good that reverberates for a long time. You’ll just never know.

On shelves now.

Source: Final copy sent from publisher for review.

Filed under: Best Books, Best Books of 2020, Reviews, Reviews 2020

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

2024 Books from Pura Belpré Winners

Winnie-The-Pooh | Review

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

Finding My Own Team Canteen, a cover reveal and guest post by Amalie Jahn

ADVERTISEMENT