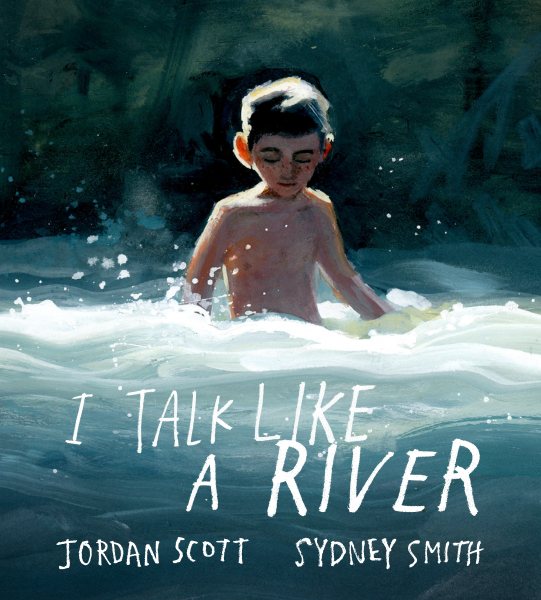

Review of the Day: I Talk Like a River by Jordan Scott, ill. Sydney Smith

I Talk Like a River

By Jordan Scott

Illustrated by Sydney Smith

Neal Porter Books (an imprint of Holiday House)

$18.99

ISBN: 9780823445592

Ages 4-7

On shelves September 1st

James Earl Jones stuttered. Marilyn Monroe stuttered. Joe Biden, Tim Gunn, Samuel L. Jackson, Kendrick Lamar, Nicole Kidman, the list goes on and on and on. Children’s books about stuttering? Thin on the ground. When you’re a children’s librarian, every interaction on the reader’s advisory desk can feel like a game of trivia. And if a child or parent comes up to you, asking for children’s books where a character stutters, or maybe just a picture book where stuttering is discussed, lord help you. Until the moment I Talk Like a River was introduced to me, the sole book for kids I would have been able to conjure up from memory would have been the Newbery Award winning middle grade novel Paperboy by Vince Vawter. A fine and worthy book, but not one that could claim to be all things to all people. If you wanted picture books with stutterers there are plenty of books out there with titles like Katie: The Little Girl Who Stuttered and Then Learned to Talk Fluently or Stuttering Stan Takes a Stand. Serviceable books with pointed reasons for existing. Not beautiful books. Not books that speak beyond themselves. Not, in short, I Talk Like a River. Deft poetic language pairs with the resonant watercolors of Sydney Smith to create a book that is more than a memoir and more than conveying a message. This is pain, turned into art, and written for young children. Incomparable.

“I wake up each morning with the sounds of words all around me.” It is one thing to know these words. To understand what these sounds are. It is another thing entirely to speak them. The boy explains that certain letters in particular can give him trouble. For example, the “P” in “pine tree” might grow “roots inside my mouth and tangles my tongue.” “C” and “M” fare little better. On this day, the boy is called to speak in front of the class. By the time his dad picks him up after school, it’s been a “bad speech day”. The two walk along the river and in time his dad tells him that the river’s rolling, breaking, bubbling habits are like his son’s. His son talks like a river. It’s not a magic cure, but it helps. Now, when the boy has trouble, he thinks of it. After all, “Even the river stutters. Like I do.”

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Purposeful picture books are picture books with jobs to do. They focus on a specific need and then go out there to meet that need with all the delicacy of a drill sergeant on the line. These are message books. They exist so that parents, desperate to show their children that they aren’t alone in the world, will have something to show them. Whether the books are about a jailed parent, peanut allergies, or even, say, a stutter, they are not built for beauty. You can’t really blame them for that. We didn’t invent them back in the 17th century to be pretty, after all. But, you see, that’s why it’s important to keep a sharp eye out for books that take a little time to break away from this mold. Jordan Scott’s words are the first indicator in I Talk Like a River that there is more going on here than representation. To read this book is to listen to Scott list and categorize words. I read this book not knowing it was a book about stuttering. I’m kind of sad that I’ve stolen that same surprise from those of you reading this review because if you walk into this book cold, without any context (the cover and title aren’t giving anything away) then you will get to these lines and not understand: “I wake up each morning with the sounds of words all around me. And I can’t say them all.” This is the introduction to the stuttering. The word “stutter” does not appear once in the picture book text, but the descriptions of what stuttering feels like ring true.

According to a note in the back, Jordan Scott’s father really did say that young Jordan’s stuttering was like the river. Or, rather, he said, “You see how that water moves, son? That’s how you speak.” Part of what makes Scott’s comparison between a stuttering mouth and a river so sharp is the fact that it’s not a perfect pairing. You can tell someone they leap like a frog and that’s a pretty straightforward one-to-one comparison there. But to say that someone speaks like a large, moving body of water demands a little something extra from the listeners. The dad in this book isn’t trying to come up with the perfect equivalent to stuttering. He’s working with what he has, and what he has before him is a river. It just so happens that the imperfection in the comparison makes it absolutely perfect.

I like to read Sydney Smith books partly to see what he does on any given page and partly to see what he doesn’t do. What an artist paints is almost as interesting as what an artist makes sure not to paint. Take, for example, that first shot of the classroom when our narrator says, “At school I hide at the back of the class. I hope I don’t have to talk. When my teacher asks me a question, all my classmates turn and look.” The page on the left is a half page image of a teacher at the front of a class. The teacher’s face is indistinct, but the paints used for this image are placed in cool, clear lines. The picture on the opposite side, taking up the whole page, is an image of all the classmates turned towards you, the reader. You are in the narrator’s shoes, and their faces too are blurred. But there’s more going on here than just that, isn’t there? The edges of the room have grown indistinct. The paints are fuzzy, almost resembling mold, and the colors have dimmed and dulled. You stare at that picture and the sheer levels of discomfort the boy is feeling come off of the page in waves. It’s a claustrophobic image, and a nightmare scene for any kid who has ever wanted to avoid being seen in this way. The image is what Smith has decided to include, but it works because what seemed so clear before has now been taken away from you.

And right now I want to pull out that old phrase, “I don’t know how he does it,” to describe Smith’s art. The statement is literally true, but sounds so hackneyed and overused. Yet how on earth do you draw the reflective nature of a river? How do you make some parts of that river seem closer and others farther? How do you use thick paints to show the wake behind a duck’s body on that water and even though there’s nothing photorealistic about it, the duck and the river and the wake all look 100% real? Or what about the next page where the setting sun (this is an autumnal time of year so that sun’s on the move) peeks at you from behind a tree and you wince when you look at it, readers. Honest-to-goodness you wince. Because somehow a mix of white and yellow pigment convinced you, if only for a second, into believing that you were looking at distant incandescent plasma. I could, at this point, write entire novels about the way in which Smith paints light through ears and earlobes, but I’ll spare you. For now.

Shared amongst friends recently, one person I read this book with wondered whether or not it would be of any interest to children. Does I Talk Like a River have sufficient child appeal? Regardless of how you feel about this particular book, that’s a pretty good question to ask yourself on a regular basis when you’re judging works for children. If the book in your hands only pleases adults over the age of 25, something’s gone wrong. So when I reread the book all by myself, I tried to see what about it that could appeal to kids. Obviously kids with stutters would like it, but what about kids that don’t? Yet let’s go back to some of those other points we were discussing. The lyricism in the language. The art in the paintings. That Author’s Note at the back called “How I Speak” might be something you eschew for most young people, but I think Scott nails the child-appeal angle. I don’t care what kid you are. When there’s something that makes you stick out from the crowd, something you don’t like about yourself, and then an entire classroom of heads turns your way, you’re gonna identify with that feeling.

I wonder when picture books first started to market themselves directly to consumers with medical or personal difficulties? Some publishers have whole imprints dedicated to producing such books. This book’s publisher would not fall into that category, and yet it has produced a work of beauty that also happens to have a purpose. It builds empathy with stutterers, but might I offer a suggestion? If a teacher or librarian has a child in their class who stutters, I pray that they do not read this book by preceding it with a statement like, “Now THIS book is about stuttering, just like Josh over there. Josh, you’re going to LOVE this!” It’s going to happen. There’s no avoiding it. But hopefully in most cases the teacher/librarian will ease it into the reading without making a big show about it. Because taken in the right vein, at the right time, for the right reasons, I Talk Like a River could make a significant difference in a kid’s life. Or an adult’s. Or pretty much anyone’s. It’s just that good.

On shelves September 1st.

Source: A electronic galley sent from the publisher for review.

Videos: Listen to author Jordan Scott discuss the book himself:

Filed under: Best Books, Best Books of 2020, Reviews, Reviews 2020

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Name That LEGO Book Cover! (#53)

K is in Trouble | Review

Fighting Public School Book Bans with the Civil Rights Act

ADVERTISEMENT

Yeah