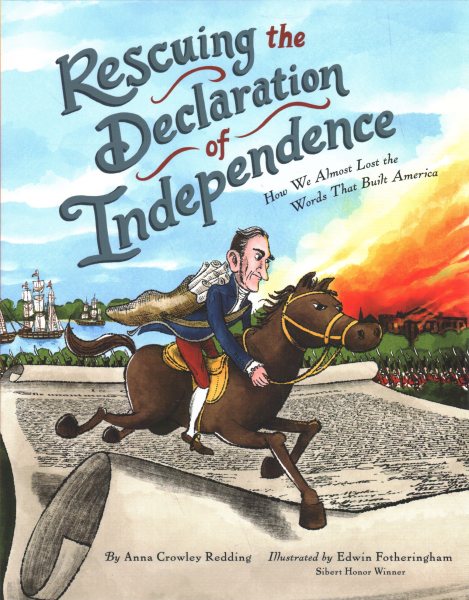

Review of the Day: Rescuing the Declaration of Independence by Anna Crowley Redding, ill. Edwin Fotheringham

Rescuing the Declaration of Independence: How We Almost Lost the Words That Built America

By Anna Crowley Redding

Illustrated by Edwin Fotheringham

Harper (an imprint of Harper Collins)

$18.99

ISBN: 9780062740328

Ages 6-10

On shelves now

The other day I was listening to a RadioLab podcast about the ubiquitousness of fallout shelters in the 1950s (Episode: Atomic Artifacts). It was fun hearing how panicked America was at the time, even as I studiously ignored the fact that even without a bunker many of us are hunkering down right now. At one point on the episode it was revealed that the United States government was so afraid of the possibility of being bombed and having to restart America that they had made a list of the documents and objects most important to save in the event of certain annihilation. Some were unexpected (a log from the Merrimack?), some had aged particularly badly (a painting of Lewis & Clark), and some were precisely what you’d expect; The Articles of Confederation, the Declaration of Independence, the U.S. Constitution, etc. But as the episode continued and started to ask other people what they would save, talk turned from thoughtless patriotism to a considered study of the worth of a symbol. Why do we deem these physical documents so important when the very point of them is that they represent ideas in flux? That’s a worthy question that I think bears some serious consideration. In the case of Rescuing the Declaration of Independence, the true story of the man responsible for keeping key American documents out of the hands of the invading British of 1812, it is worth exploring the difference between your own complicated feelings about what a piece of paper represents, and what happens when someone removes your choice from the equation, trying to take it away from you by force. This is a book about the rescue of ideas put to paper.

Nobody remembers the name “Stephen Pleasonton”. He did not appear in our history books as children. There are no portraits or epic painted scenes made in his honor. Yet on August 22, 1814, Stephen was literally sent a call to action. That day he had received a message from his boss, Secretary of State James Monroe. The British army had dropped off its troops just outside of Washington and they were headed his way. And since Stephen was in charge of such documents as the U.S. Constitution, the Articles of Confederation, and the Declaration of Independence (amongst other things) maybe it wouldn’t be the worst idea to move them. Like, now. Right now. What follows is an epic story of makeshift solutions and desperation as Stephen works against the clock to move and save items that would have been much desired by the invading forces. Backmatter includes an Author’s Note, information on The Declaration of Independence, the U.S. Constitution, the Articles of Confederation, a Timeline for the Burning of Washington, information on where you can see the documents today, and a Selected Bibliography of titles.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

My husband had been in charge of the bulk of the in-house learning with the kids during the COVID-19 pandemic. Given a certain amount of free reign to teach as he saw fit, he decided thorough history lessons were in order. So when I asked him later what they’d covered, he gave me the run down. “What about the War of 1812?” I asked. Turns out, he hadn’t really covered it all that much, and little wonder. When trying to encapsulate history in brief, you cannot include everything. And The War of 1812 doesn’t really sell itself all that much. Which one was that again? Was it the one where legend says Dolly Madison cut the portrait of George Washington out of its frame to save it when the British came to burn down Washington D.C.? That’s the one. The war that Canadians generally understand a lot better than Americans do. Seems to me that if you’re going to do big moments in history right, you need a hook that actually interests people. Someone gunning for the Constitution? That’ll do it.

Author Anna Crowley Redding is no stranger to informational books for kids and teens, but her subject matter is usually a bit on the contemporary side. Histories of Google or Elon Musk. That sort of thing. Rescuing the Declaration of Independence is a bit of a gear shift for her and as with all picture book nonfiction I viewed the book with a sharp eye. It would be easy to slip in chunks of fake dialogue in as an exciting story as this one. Yet Redding withstands the temptation time and time again. So now that she’s sticking to the facts (as we know them) what’s her premise? Is it all nationalism, rah-rah-, yay yay U.S.A., or is there another tactic at work? Look, I’m not gonna lie to you. There are some definite rah-rah elements. However, it’s less fixated on America than it is on the documents themselves and what they represent. One could argue that you could hardly discuss one without the other, but there’s another element to the storytelling that’s interesting. One of the last sentences in the narrative is that we have the original documents, “because an ordinary clerk did an extraordinary thing.” I flipped back after reading that, and it’s clear that the book is showing you that nobody on these pages was infallible or some kind of super human. Mistakes were made, and corrected, and made again. Reading the book, you sort of get the sense that you’re watching something like “Apollo 13” where solutions have to be crafted on the sly.

Now perhaps you think that any two-bit author with a laptop and some drive could whip out an exciting story about Pleasonton’s actions, but I watched with great interest the way in which she chose to frame the story. First off, she’s not going to go into the rudimentary details of why the War of 1812 happened. Good thing too or you’d have your kid readers snoozing before you got to page four. Right off the bat you learn that we were at war, we won, and then we went to war again. Then you get the fast ride from where the British are disembarking to our hero. At no point does Redding say that Stephen was a nerd, but come on. He looks very happy with all that paper around him. And when the call comes in to remove the documents, that’s when the book needs to make things peppy. Making bags, staring down a General, flagging down fleeing farmers, dumping everything in a gristmill, forgetting the Declaration of Independence (that’s my favorite part), and then picking EVERYTHING up again and taking the stuff to an empty mansion. Foof! End with a shot of the White House on fire and your job is done. It’s fast. It’s peppy. And there’s that nice little feeling of urgency to make it work as a whole.

Illustrator Edwin Fotheringham, when he is remembered in history, will someday be regarded as The King of the Historical Work of Picture Book Nonfiction (of course, they’ll probably have a catchier name for him than this). And while he does not specifically specialize in the Revolutionary era, sometimes it feels that if he isn’t talking about John Adams or Thomas Jefferson then he’s dishing on Thomas Paine. Stephen Pleasonton poses a new challenge for Mr. Fotheringham. To wit, he is unknown to the American people as a whole. Not a household name by any stretch. So Fotheringham does something very interesting with his art in this book that I’ve never really noticed him doing before. Everything in this book is digital, but he is able to replicate different kinds of physical art with aplomb. Now normally when I think of his style, I think of pen and inks. But look at the great splotches of colors he uses for mass crowd scenes or in the thought bubbles of characters talking. There’s one scene in particular that really caught my eye. Pleasonton is trying to convince General Armstrong that the British are coming. As he speaks you see troops, faceless blotches of color, running forward en masse. Armstrong counters that D.C. isn’t worth invading and his speech bubble contains big gray bugs, swamps, and a distant White House. It’s subtle, but I like how he foregrounds the characters in pen and inks and renders everyone in the background a blur of action with what looks like watercolors. Kicky.

One thing that we must be vigilant and continually check for in our historical picture books, of course, is representation. In the past an artist would paint a town like Washington D.C. with countless white citizens and the white reviewers wouldn’t even notice. These days, that racist view of history doesn’t (or at the very least, shouldn’t) fly. Fotheringham is interesting in that respect. The major players in this book, from Monroe to Pleasonton to General John Armstrong are all white. This can make it hard for an artist, so what you really need to do is to examine how the illustrator handles crowds. Are the crowds in this book a sea of white faces or is there some variation there? And consistently, in every single crowd scene I could find in the book (with the exception of a crowd of British soldiers) there is as much brown skin as white skin.

The truly great advantage of our constitution is that it is not a fixed point. Oh no, it is an ever changing document, that can be improved upon. When I worked at New York Public Library there was a yearly event that amused me. You see, while Stephen Pleasonton may have saved the original Declaration of Independence, NYPL owns another one. Every year for the 4th of July they put it on display for a little while so that the public can see it. It sort of reminds me of that scene in Monty Python and the Holy Grail where the French soldiers are invited to join King Arthur on his search for the grail and beg off saying, “We’ve already got one!” Still, a lot of people get a real kick out of seeing an item that was written or held by a historical figure. And almost as enticing as the idea of seeing it is the idea that we almost didn’t see it. That it could have been lost in one fell swoop. At its heart, Rescuing the Declaration of Independence is an action movie with a famous star (the documents). And afterwards, you can talk to your kids about whether or not a physical object like a Constitution needs to be preserved and visited or if its merits are found in different ways. And for folks that want to give their teaching of the War of 1812 a more interesting hook, this isn’t a bad way to go about it. An interesting take.

On shelves now.

Source: A final copy sent from the publisher for review.

Filed under: Best Books, Best Books of 2020, Reviews, Reviews 2020

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Name That LEGO Book Cover! (#53)

K is in Trouble | Review

Fighting Public School Book Bans with the Civil Rights Act

Take Five: Middle Grade Anthologies and Short Story Collections

ADVERTISEMENT