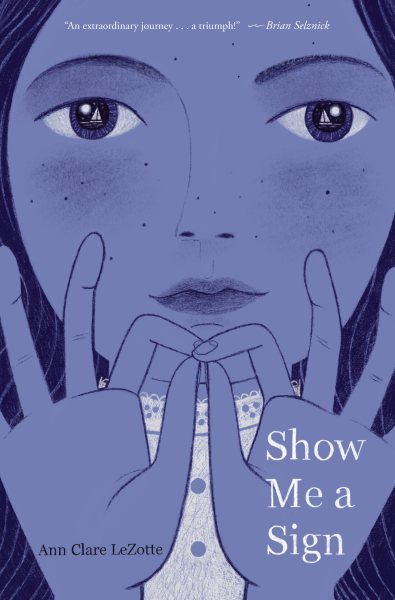

Review of the Day: Show Me a Sign by Ann Clare LeZotte

Show Me a Sign

By Ann Clare LeZotte

Scholastic

$18.99

ISBN: 978-1-338-25581-2

Ages 9-12

On shelves now

“Not every writer comes to English from the same direction.” Right now I’m sitting here as a reviewer, trying to figure out from which direction I should approach this book. In the pantheon of children’s literature about the differently abled, stories about people in the Deaf community or along the spectrum of hearing loss, are not common. Such books exist, of course the most notable examples being Wonderstruck by Brian Selznick and El Deafo by Cece Bell. Yet I worry that things have not changed significantly since I was a kid. When I was little we had books about Helen Keller and … that was pretty much it. If you were to pull aside a sixth grader today and ask them to name a book featuring a Deaf main character, would they still think only of Helen? Author Ann Clare LeZotte is a Deaf librarian and brings to Show Me a Sign the ability to pinpoint the subtleties of the white, deaf residents of Martha’s Vineyard. This is a work of historical fiction that brings to light a specific community we’ve not seen in a children’s book before. And just wait till you hit that twist in the middle of book!

“If you are reading this, I suppose you want to know more about the terrible events of last year – which I almost didn’t survive – and the community where I live.” So begins Mary Lambert’s story. Deaf from birth, she lives on Martha’s Vineyard (land “sold” by the Wampanoag who reside there still) in 1805 in the village of Chilmark. In this isolated community many people are deaf. In Mary’s own family her mother and brother, recently deceased, could hear and her father cannot. Mary’s mother still grieves her dead son desperately, but distraction comes in the form of a young scientist that visits the island. Drawn to the mystery of why so many inhabitants are born without hearing, the man is determined to find the cause. Yet there is something deeply wrong with the man’s attitude, and as Mary investigates further she is pulled into a terrible discovery and grotesque new status as a “live specimen” of her people.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

I do not read in a vacuum. Often I rely on the thoughts an opinions of the other children’s librarians at my library to give me a better sense of what to and not to look for in fiction for kids. I think it’s safe to say that each reader of this book approached the material with skepticism. As one said, she worried about the common pitfalls that disability fiction (for lack of another term) often falls into (person with differing ability as angry/ own worst enemy, overcomes disability in an inspiring way, etc.). Mind you, LeZotte has explicitly made a special point NOT to write that kind of book. Indeed, she actively swerves away from that storyline type and is unafraid to say so. My librarians and I did agree that the beginning of the novel is a bit on the slow side. Well-written, absolutely, but it reminded me, in a funny way, of the first chapter of Tuck Everlasting. Great words are there, but they make the book a very slow burn straight out of the gate. I don’t find that a fault, necessarily. There’s something about the sudden switchover from its languid first half to the horrific event halfway through that makes the second half all the more gripping.

And now some thoughts on racist mamas. Amongst the many things I admire about LeZotte as a writer is her guts. It takes some guts to make a character purposefully unlikable, sure, but it takes sheer oodles of guts to make a character beloved by the protagonist a racist jerk. And LeZotte never plays it safe. She could easily have gone the Caroline Ingalls route and settled for simply making Mary’s mom a character that is closest to our heroine and that harbors horrid thoughts about the local Wampanoag population. But it’s not enough to have a mom with despicable thoughts. Oh no, LeZotte also makes Mary’s best friend, with whom she shares so much, a complicated person with awful opinions. Books set in the past starring sympathetic white characters often face a significant problem. While it would be accurate to make such heroes a product of their time, imbued with the societal prejudices they cannot escape, contemporary child readers don’t like their protagonists to be unlikable. So how do you balance accuracy with delicacy? There are a number of ways to go about it, but LeZotte’s answer may be amongst the best. Essentially, if you make two major white characters casual racists, while at the same time telegraphing that this is NOT okay, then you can give a child reader the sense of how racism can permeate a society. The difficulty comes in the inevitable redemption, of course. Mary’s friend Nancy has an abusive father and Mary’s mother is suffering from severe depression and grief, which draws a little sympathy their way. Yet neither recants her racist stance, and so it is up to the child reader to judge these characters accordingly by the story’s end. An ideal topic for a book discussion, no?

Mind you, it’s all well and good to have an open-minded white protagonist but let’s not forget that there are a few Wampanoag characters in the book. If we are examining this book through the lens of a white author writing about a Native population, what are we to make of it? In such cases as these, I defer to the experts. First up, there is the blurb on the book from Penny Gamble-Williams, “activist and Spiritual Leader of the Chappaquiddick Tribe of the Wampanoag Nation” who points out that the issues brought up in this book (“land ownership, cultural clashes, racism, and intolerance”) continue to this day. Gamble-Williams was also the sensitivity reader for the book. Next, there are the Seminole & Miccosukee teens that write on the blog Indigo’s Bookshelf. They have close ties to the author, a fact that they make mention of straightaway in their critique of this story, but they also have their well-developed senses of skepticism, which I admire. They didn’t want this book to be a “White awakening narrative” where the focus is on the main character and HER journey. They are not without their criticisms, but on the whole they feel the book is respectful and well done.

So when we talk about children’s books we sometimes talk about the “takeaway”. As in, “what will a child take away from this book?” This makes the assumption that every book we read has to have some kind of implicit moral lesson (a holdover from children’s literature’s early Puritanical roots, no doubt). And certainly there are books for kids out there that don’t give two hoots about conveying anything to their child readers. Yet in the case of Show Me a Sign, I like to think that there is a message at work that doesn’t come across as immediately obvious. It’s not even all that revolutionary, until you realize its context. It is, simply, “We are fine as we were made.” The idea that a person who is deaf does not have to be “fixed” in any way is as radical today as was during the Enlightenment. When someone says in the book that to be deaf is to live in a “reduced state”, you, the reader, feel that insult. May such casual cruelties fall by the wayside in the presence of such books as these. May our children find them and love them and read them repeatedly. And may we see more such books from Ann Clare LeZotte and authors like her, that put work and care into the very folds of their stories.

On shelves now.

Source: Galley sent from publisher for review.

Reviews:

- Again, I urge you to read the review of this book in its entirely from Indigo’s Bookshelf at your earliest convenience. It contains perspectives necessary for a rounded understanding of this book as a whole.

- Think it’s significant at all when the author of a Newbery winner is pegged to review a book for The New York Times? Hmmm? Do ya?

Interviews: Check out this one with We Need Diverse Books.

Videos:

Nice to see author Ann Clare LeZotte speak and sign about her book in this video but is anyone else SERIOUSLY bugged by the fact that the video keeps arbitrarily cutting to views of the cover when the author is speaking/signing? Geez, Scholastic. Read the room, willya?

Filed under: Best Books, Best Books of 2020, Reviews, Reviews 2020

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

2024 Books from Pura Belpré Winners

Winnie-The-Pooh | Review

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

Finding My Own Team Canteen, a cover reveal and guest post by Amalie Jahn

ADVERTISEMENT

My first career was Sign Language Interpreting (which is to say I’m fluent in ASL), and I loooove how LeZotte handles language / dialogue in this book. It’s been a while since I read it, but I recall that she only sometimes engages in ASL glossing but other times sticks to the spoken English translation of what Mary signs (in LeZotte’s beautiful prose). So much of ASL is communicated with the face and body (grammar lies in your very eyebrow movement) and the syntax is so different from English, so glossing is only half the story. I love that some glossing is included, but I love that she switches it up a bit.

Great review! Betsy, I’ll be quoting you for weeks. I’m the librarian in an ESE school. This book is tremendous for my students—it dodges every stereotype and offers up an intensely likable heroine who saves herself with the help of her Deaf community. It’s a tremendous relief when the old sea dog (with his cat) reappears on the scene. I agree with you, Julia, about the way the nuances of MVSL are conveyed, with less formality between family and close friends and the interpreter (if needed) is always well-placed—it seems simple but it’s masterfully done. The way Mary tries to teach Sign to the maid in the doctor’s home is clever. I’m also very impressed that racial segregation in Deaf schools and the traditions it created, like Black ASL, are recognized in the back matter. The truth is, Deaf kids isolated by the pandemic are more often than not at home with hearing parents who don’t Sign—they’re distanced from their communities of friends and interpreters at schools. 2020 may not be the author’s dream debut year—but it’s a perfect year for this story. Thanks for highlighting this book! It’s sure distinctive enough to win a shiny sticker. Fingers crossed.

Wow. You just placed this book into the history that we’re living right now so beautifully that I’m in awe.

Well-said, ESE Librarian Bob! I was, once upon a time, the librarian at the Tennessee School for the Deaf. I miss storytimes in ASL. There’s nothing better. … Excellent point about the effect of the pandemic on Deaf children and teens whose family don’t share their language (and in some cases don’t even share a visual language with them at all). Thank goodness for videoconferencing and things like FaceTime (for students who have access to them anyway). It can be an isolating time.

Anyway. Deaf Claps for Ann’s excellent book.

Thank you for reviewing this book. I am familiar with it from Indigo’s Bookshelf. It’s the most unique book I’ve read from a positive deaf perspective. It shows that at one time deaf people and those who can hear lived together without discord because of their deafness; they had other matters to argue over. The world is well-described for young readers. It does something else that is equally unique: it shows that Black men who were formally enslaved could enter Aquinnah Wampanoag society without discord due to their race. Wampanoag men were scarce. The Wampanoag women welcomed Black men as husbands. They fully participated in Wampanoag ceremonies and customs together. There was no “veil” to keep them away from private information. Their children were born free and could own land. This is also as radical today as it was then. According to the back of the book, LeZotte worked with two Indigenous sensitivity readers. As you say Penny Gamble-Williams who is Spiritual Leader of the Chappaquiddick Tribe of the Wampanoag Nation and Cherryl Toney Holley, the current chief of the Hassanamisco band of the Nipmuc Nation. These are both Afro-Indigenous women from Massachusetts in leadership roles. Any outsiders writing such stories must create these relationships. Even though the Native content is secondary it’s significant because the author shows that imperialism and diversity have always existed and the characters of the Richards family show Afro-Indigenous life as a struggle but a loving life. Today, Afro-Indigenous people are discriminated against, disenrolled and otherwise disenfranchised due to the greed and selfishness of Native nations who have forgotten the teachings of the ancestors. I hope this book leads to historical and contemporary stories of Afro-Indigenous lives that are not defined by the racist refusal of our existence.