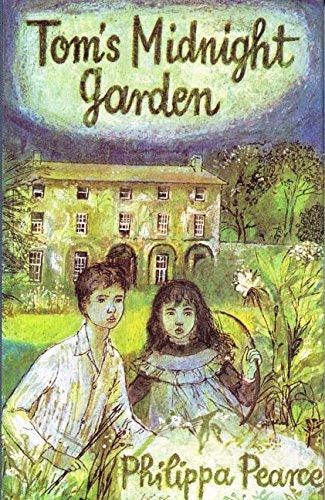

Timeless: Tom’s Midnight Garden. Guest Post by Fred Guida

It’s guest post time again, and Fred Guida has returned with another classic in mind. Remember Tom’s Midnight Garden by Philippa Pearce? Then take it away, Fred!

SPOILER ALERT: This article assumes that the reader has already read Tom’s Midnight Garden. If you have not, then do not read this article. Let nothing spoil or influence your initial experience of Philippa Pearce’s masterpiece.

What is it about Philippa Pearce’s Tom’s Midnight Garden (hereafter referred to as Tom), which was first published, in 1958, by Oxford University Press? Why did it win the Carnegie Medal, the United Kingdom’s highest award for excellence in books for children or young adults? Why is it considered a modern masterpiece? Why has Philip Pullman called it “a perfect book.”¹ The answer may be as simple as “because it is a perfect book.” And let us be clear, while it is technically a children’s book, there is nothing “childish” about it. Philippa Pearce was not in the business of underestimating or talking down to children, nor was/is Oxford, one of the world’s most prestigious university presses, in the business of publishing “childish” fluff.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Like many great works of fiction, the roots of Tom can be traced back to its author’s own life. To begin with, the major talking points on Pearce’s résumé reveal a very interesting life indeed. She studied English and History at the University of Cambridge, and, over the course of her career, was a civil servant, a writer and producer for radio, an editor, a book reviewer, and a lecturer. And, of course, she was a prolific writer of the first rank, producing novels, short stories, and picture books.

However, it is when we look deeper that the genesis of Tom and Hatty’s garden comes into focus. (Ann) Philippa Pearce was born in 1920, in the village of Great Shelford, Cambridgeshire county, England. Her father was a flour-miller and corn-merchant, and she grew up in Kings Mill House, adjacent to the mill itself which was located on the River Cam. Significantly, the book’s garden, and the house to which it is attached, were based closely on the mill house and its garden as they appeared in her father’s childhood. In the 1950s the house and its garden were sold, and she was also inspired by her thoughts and fears of what might become of them. But yes, there was — and still is — a real garden!

For the purpose of some of her fiction, including Tom, Pearce put a creative spin on the Cambridgeshire countryside. Thus, the villages of Great Shelford and Little Shelford became Great Barley and Little Barley. And the major city of Cambridge became Castleford minus the famous university. Oddly, the cathedral city of Ely, which figures prominently in Tom, retained its real name. And running throughout, the omnipresent River Cam became the River Say. Although not specifically mentioned in the book, all indications are that, since the real house and garden were located in Great Shelford, Pearce placed Tom and Hatty’s garden in, or very close to, the renamed Great Barley.

In this regard, the reader who wishes to flesh out further details of Tom’s setting is referred to the books that immediately preceded and followed it, Minnow on the Say (1955; published in the United States as The Minnow Leads to Treasure), and A Dog So Small (1962). These books are highly recommended as companion pieces to Tom, although Tom should definitely be read first; Minnow should be read after Tom, and Dog, which contains a direct link to Minnow, should be read last. It must be noted, however, that while reading Minnow and Dog can be useful in terms of shedding some light on Tom’s geographical context, they never detract from its status as a stand-alone masterpiece. (Pearce’s reimagining of the Cambridgeshire landscape is also evident in several of her short stories.)

So, what is Tom all about? What kind of book is it? At first glance, its basic plot sounds like pretty familiar stuff: In the middle of the night, a clock mysteriously strikes thirteen, and the protagonist gets out of bed to investigate. However, as anyone who has read the book knows, there is nothing lazily formulaic about it, nor is it just a modern take on The Secret Garden.

In terms of genre, the book is invariably classified as a fantasy. If we must have a one word description of it, fantasy is accurate. And without getting into a discussion of high versus low fantasy, or time-slip fantasy, we all know what a fantasy is. And yet this description is also incomplete. Pigeonholing it as just a fantasy is simply wrong. It is so much more.

However, to the extent that the book is a fantasy, children believe, they know, that anything is possible. In this sense, there is nothing impossible about the events that unfold in the book. Unusual perhaps, but definitely not impossible. As such, the book has great intrinsic appeal to young readers. But what accounts for its considerable appeal to adults, beyond the obvious fact that one is quickly pulled into a cracking good mystery? The answer is that it offers hope to the adult who has retained even the slightest glimmer of wonder about life. It offers the hope that there might be something different, something better, beyond the scope of “normal” adult experience. It tells the adult that Oz, and Narnia, and Rivendell, just might be real places, places that might be found around the next corner or through that previously unnoticed door. What Gore Vidal said of L. Frank Baum is also true of Philippa Pearce: “…Baum was a true educator, and those who read his Oz books are often made what they were not — imaginative, tolerant, alert to wonders, life.”² Again, Pearce’s book is so much more.

Regarding the idea that it is possible, for both the child and the adult, to find his or her own Shangri-La, a palpable tension permeates the book. It poses the question of whether paradise, once found, can be lost. There is a moment when, on one of his midnight journeys, Tom is momentarily afraid to open the door for fear that the garden might not be there. Fortunately for him, he overcomes his fear and discovers that the garden still awaits. But the tension is real, and it is terrifying. As such, we understand Tom’s pain when, on his last night in his aunt and uncle’s flat, he discovers that the garden is not there. We understand his profound anguish when he desperately calls out Hatty’s name. It is a deeply disturbing moment. Children should not be made to suffer like this. But, says the adult, neither should I.

To return to the thorny question of genre, as suggested above, Tom is also a very complex mystery — and its central character turns out to be an excellent detective. In this regard, Pearce demonstrates a profound respect for the basic intelligence of children. As such, Tom is painted as highly intelligent, resourceful, and fully capable of rising above the restrictions placed upon him by well-meaning, but ineffectual, adults. In a very real sense, Pearce paved the way for all of this in her previous book Minnow on the Say, which was a runner-up for the Carnegie Medal. Part Swallows and Amazons, and part Hardy Boys, Minnow is a complex mystery that would make Agatha Christie proud. And, as in Tom, its young protagonists are excellent detectives.

So, while it is primarily known as a fantasy, and largely unheralded as a mystery, a case can be made that Tom also functions as a kind of quasi science fiction. According to Pearce, the theory of time that underlies her book was inspired by the work of British philosopher J. W. Dunne, particularly his books An Experiment with Time (1927) and Nothing Dies (1940). The former was very popular and influenced many earlier writers, particularly J. B. Priestley. One of Dunne’s theories is that all time — past, present, and future — occurs concurrently. Or, to put it another way, there is only one overarching time, and our concept of linear time is the only way in which the limits of human consciousness can perceive it. This theory is articulated several times in Tom, as when Tom tells us that he “might be able, for some reason, to step back into someone else’s Time, in the Past; or, if you like … she [Hatty] might step forward into my Time, which would seem the Future to her, although to me it seems the Present.”³

Within the context of a belief that time is flexible, and that past, present, and future are relative concepts, there is the matter of dreams. Dunne’s theories of time are closely intertwined with his theories of dreams, and the subject is also of great interest to Pearce. For her, the power of Hatty’s dreaming has brought the garden to life again. However, it is crucial to remember that while Hatty is dreaming, Tom is not. Something else is going on here. A lesser writer, writing a lesser book, would have told us that Tom dreamt it all. To her credit, Pearce avoids the tired cliché of turning Tom’s experience into a dream. She avoids the mistake made by the famous 1939 film adaptation of Baum’s Wizard of Oz which, in explaining away Dorothy’s experience as a dream, is ultimately an insult to those who have read his books. Pearce does not insult her readers. Instead, we witness a kind of mind melding in which the intensity of Hatty’s dreams meets the intensity of Tom’s desire — and the result of this meeting is nothing less than a new definition of reality. Simply put, we are talking about the basic power of the human mind itself. We don’t really know how Edgar Rice Burroughs’ John Carter gets to Barsoom, but we accept the reality that he does.⁴ So it is with the friendship of Tom and Hatty, confirmation of which comes when an old woman touches the arm of a young boy and determines that he, and her memories, are real. In the final analysis, Pearce obviously does not deny the existence, strength, or versatility of dreams, quite the opposite is the case, but she does give her readers credit for being able to comprehend something much more complex.

It is also worth noting here that Pearce wrote many excellent ghost stories. However, she does not reach for this device in order to explain the mystery of Tom and Hatty. With all due respect to what is a legitimate literary genre, to do so would have been to take another easy way out. Instead, we are provided with further proof that Pearce is a very sophisticated writer, and that Tom is a very sophisticated book.

And finally, having established that the book is a unique blend of fantasy, mystery, and science fiction, it must be noted that it is also one more thing. It is an idyll depicting not only a magical summer in the life of a young boy, but also a kind of cosmic romance that transcends the limits of time and place. And there is a magical, lyrical, indeed mystical, quality about the book that is hard to define, but impossible not to feel. It is also poignant, poetic, imaginative, elegant, enchanting, enthralling, sensitive, beautiful, absorbing. And, to paraphrase Dickens, it haunts the reader pleasantly.⁵

And so, if Pearce reveals herself to be unconstrained by stifling definitions of genre, she also demonstrates that she is highly adept at creating multidimensional characters and, in so doing, commenting on various aspects of the human condition. For example, in addition to his being painted as highly intelligent, the book avoids the cliché of presenting its hero as a stereotypical “lonely child.” Tom comes from a good family, he is loved, he is not abused in any way, and he has a close relationship with a beloved brother. He has simply been thrust into a difficult situation by circumstances beyond anyone’s control. Yes, when he first arrives at his aunt and uncle’s home, he does experience loneliness and boredom. But these feelings are quickly dispelled once he discovers the garden, and Hatty.

Nevertheless, Pearce does have much to say on the subject of loneliness. For example, it is a telling, and touching, moment when the elderly Hatty, in speaking of her first real conversation with Barty, tells Tom that “I’d never really talked to Barty before then, for I was shy in company — I still am, Tom.”⁶ The key word here is “still,” because earlier Pearce makes a subtle, and quite profound, observation. It occurs during one of Tom’s visits to the garden during winter. He observes a group of skaters, laughing and having fun on the ice. Then we are told that “one could guess which among the skating-party might be Hatty herself: a girl who was among all the others at one moment, and then, at the next, would be speeding alone over the ice. A habit of solitude in early childhood is not easily broken. Indeed, it may prove lifelong.”⁷ Even a casual reading of Tom reveals a bittersweet undercurrent that is often simmering just below the surface. This is one of several moments when it rises to the top.

While reading the book, we are constantly reminded of how beautifully written, and well- constructed, it is. There is not a wasted word, everything means something, and Pearce’s powers of description are constantly revealed to be subtle yet stunning in their effectiveness. For example, as described, the garden is a real place. You can smell the grass and feel the sun, your eyes are blinded by lightning striking a tree, and, in winter, you can see your frosty breath and hear the crunch of snow. In short, her ability to paint a picture with words is positively Dickensian. (With regard to the book’s original illustrations, artist Susan Einzig based her evocative drawings of the house and garden on Pearce family photographs and paintings.⁸)

Again, there is not a wasted word. Every sentence advances a very sophisticated plot; and whether ruminating about the past, present, or future, the greater whole is constantly moving forward toward an unforgettable climax. However, it is also a book of memorable moments and episodes that are clearly part of that greater whole, and yet which linger in memory as beautiful and meaningful set pieces. For example, there is the heart-wrenching scene in which Tom encounters the very young Hatty, dressed all in black, and grieving piteously for her dead parents. And then, on a larger scale, there is the skating episode. Spread out over two chapters, it contains two of the book’s most memorable moments, one exhilaratingly happy, the other profoundly sad. The skate to Ely itself, which was inspired by the same youthful experience of Pearce’s father, is an emotional tour de force, and an idyll within an idyll. The prose is simple and straightforward, yet brilliant in its evocation of the freedom, the movement, the sheer existential joy, experienced by Tom and Hatty as they skate. It is a vignette worthy to be counted among the finest in modern children’s literature. Children and adults alike enjoy it, but sensitive adults are also tinged with a kind of yearning that might even border on envy.

And then there is the episode’s climax when, while skating home from Ely, Tom and Hatty encounter young Barty who gives them a lift in his gig. As they travel, the more that Hatty speaks with Barty, the less she notices Tom. Then, when they arrive home, we are told that “when Mrs Melbourne, coldly amazed and angry, came to the front door to receive them, she saw only two people in the gig: that was to be expected. But even Hatty saw only one other besides herself, and that was young Barty.”⁹ The scene confirms what Tom and Peter learned earlier atop the Ely cathedral tower: Hatty is no longer a child. Our hearts break for Tom, we understand what he has just lost — but the reader, certainly the adult reader, while happy for her blossoming romance, also mourns for what the suddenly grown up Hatty has lost.

In addition to such meditations on personal loss, it is essential to understand that the book also manages to directly confront what might be termed larger societal losses. For example, there is Tom and Aunt Gwen’s brief but disturbing conversation about the pollution of the nearby river. However, the crucial issue here is the way in which the book depicts the end of an era. Call it modernization, or urbanization, but above all call it change: The age of Victoria draws to a close. A village begins the process of becoming a town. A business fails and a once proud family gets its comeuppance. New small houses spring up and crowd and choke the manor house. The house is sold and divided into flats. Even the garden is sold. And all of this happening against the backdrop of the inexorable march toward the catastrophe of the First World War, a conflict which, we later learn, will change Hatty’s life forever. Working in an American milieu, Booth Tarkington covered similar ground in The Magnificent Ambersons and won a Pulitzer Prize for his efforts.¹⁰ Although working on a smaller scale, Pearce is no less successful.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

But, having said this, it is equally essential to bear in mind that Pearce also offers hope. Yes, everything changes. Time does move. But maybe J. W. Dunne was right. Maybe we just haven’t figured out yet how it moves. Who knows what modern science may yet discover about time — and about the power of dreams. Again, Pearce offers hope. And, as noted earlier, the hope that she offers also extends to the possibility that there might be something different, something better, that we can hope to find. Children know that there is. And, in Tom Long’s case, this voyage of discovery culminates in one of the most moving and unforgettable resolutions in literary history.

Notes

1 Promotional endorsement on the back cover of the 2018 60th Anniversary Edition of Tom published by Harper Collins/Greenwillow.

2 Vidal, Gore. On Rereading the Oz Books. The New York Review of Books, October 13, 1977.

3 Philippa Pearce, Tom(New York: Harper Collins/Greenwillow, 2018), 230. 60th Anniversary Edition.

4 See A Princess of Mars, first published in book form in 1917; the definitive edition was published by the Library of America in 2012. The story was originally serialized in 1912, under the title Under the Moons of Mars, in The All-Story magazine.

5 See the Preface to A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens.

6 Pearce, Tom, 293.

7 Pearce, Tom, 232 –233.

8 The 60th Anniversary Edition of Tom that has been quoted herein does not include Susan Einzig’s original illustrations. This is most unfortunate as they make an important contribution to the overall fabric of the book.

9 Pearce, Tom, 274.

10 First published in 1918, there have been many editions of The Magnificent Ambersons. The definitive edition will be found in Booth Tarkington: Novels & Stories (Library of America, 2019).

Filed under: Guest Posts

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Happy Poem in Your Pocket Day!

Family Style: Memories of an American from Vietnam | Review

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

ADVERTISEMENT