Guest Post – Beyond 3 Percent: Translated Children’s Literature in the U.S.

I am very delighted to announce that we will be hosting monthly pieces on this site from none other than David Jacobson. Starting today you will be privy to works on children’s literature translation that may shine a bit of a light on issues in the field that you may not discover elsewhere. David is the author of the magnificent picture book biography Are You an Echo? The Lost Poetry of Misuzu Kaneko, which I found to be one of the more remarkable books of 2016. You may find his other credentials at the end of his piece.

And so, without further ado, take it away David!

In 2007, translator Esther Allen published an essay in the PEN Club International report To Be Translated or Not, citing data that translations amounted to a paltry 3% of new books published in the United States.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

That number has continued to be cited in discussions about the ostensible lack of translations published in this country. Fortunately, it does not reflect the striking growth that has taken place during the last decade, especially in children’s books.

The Cooperative Children’s Book Center (CCBC) at the University of Wisconsin is the source of the most authoritative data on translated children’s literature. In 2018, it counted 169 children’s books in translation, about 4.56% of the total it received. That number has increased an average of 9% each year since 2002, when the CCBC identified only 75 translations, representing 2.38% of the total books that year.

(tabulation)

That is a “huge jump,” says Bindy Fleischman, chair of the US Board on Books for Young People’s (USBBY) Outstanding International Books (OIB) committee. By contrast, Fleischman calculated that imported children’s books constituted 3.5% of total children’s books in 1998-2002 for her 2003 master’s project at Simmons College. That figure, however, also included English-language imports from countries like Canada and the U.K., in addition to translations.

It is possible that the gains are even bigger. The CCBC only counts those titles that are voluntarily submitted by publishers, and therefore likely undercounts the total number of translations. In its description of its methodology, the CCBC notes the limitations to the data it collects:

The CCBC receives most, but not all, of the trade books published annually in the United States by large corporate publishers. The CCBC also receives books from some smaller trade publishers in the United States and a limited number of series or formula non-fiction books published here. We also receive books from several trade Canadian publishers that distribute in the United States. More recently, we’ve begun receiving a small number of books distributed by a few U.S. trade publishers with a U.S. price label, but not in a U.S. edition. We also receive a small number of independently published and self-published books. (CCBC, 2019)

These limitations may have particular impact on the number of translations counted, because translations are published disproportionally by small and foreign publishers (Jacobson, 2017.) According to longtime translation advocate and Open Letter Press Publisher Chad Post, 86% of translations have continued to be published by small presses since he began his Translation Database (now hosted by Publishers Weekly) in 2008.

Ellen Myrick, who specializes in international book marketing, sees the change in both numbers and general openness to different kinds of books. “Over the last 10 years, I have seen broader acceptance and appreciation of lit from across the world,” she says. Her business, Myrick Marketing & Media, has expanded every year since it opened in 2007. As the former director of marketing for North-South Books, Myrick notes “I used to hear that they [North-South] were too European. I never hear that any more.”

They are noticing the change in Europe, too. Consultant Rüdiger Wischenbart, author of “Diversity Report 2018: Trends in Literary Translation in Europe” notes the rise of “authentic interest” in translations among English-language publishers in the UK and the US.

How do we account for this growth?

Rutgers University Professor Marc Aronson is one of a handful of library school professors teaching international children’s literature. “There was an age of great editors and publishers who were very international in their outlook… but when their age ended, international children’s books disappeared. YA and especially fantasy and dystopia boomed and became so dominant, large houses focused there.”

“As the big houses have gotten hyper big,” Aronson continues, “small individualistic publishers with real insight and knowledge and commitment to international books” have stepped in. Aronson names publishers like Cinco Puntos and Enchanted Lion. Others might include Elsewhere Editions, Yonder, and Pushkin Children’s in the U.K.

“In a way, since ‘international’ was so neglected, there was opportunity,” he says.

Ellen Myrick credits USBBY and especially the OIB list in broadening interest and support for international literature, especially in the library world.

“They were really, really smart. They did not just create a list, but they also [published] an article in [the February issue of the] School Library Journal, which talked about the books in detail, discussed trends, and really celebrated them. It gave people who had an interest in [such books] a place to find the best of the best for a given year.”

Myrick says she has been submitting books to the OIB from the very beginning, and when her books have been selected, it gives them “authority and credibility.” You can also see sales jump by getting included in OIB, she says.

Since its founding in the early 1960s, USBBY has engaged in multiple efforts to expand the reach of translations, such as by promoting International Children’s Book Day (which was developed by its parent organization, the International Board on Books for Young People), and through its five-volume series of annotated bibliographies of international literature. It is particularly significant, then, that in the last few years, a number of other organizations have joined in, suggesting a groundswell of interest in translated literature and a desire to broaden its reach.

- In 2018 the National Book Foundation presented the first awards for its new category of books in translation (though not specifically for youth literature), in which the prize money is split between the author and the translator.

- Also that year,

a committee reviewing the Batchelder Award, an American Library Association

award that goes to the publisher of the best books in translation, decided to

broaden the types of books it will consider to folklore and non-traditionally

published translations.

- And in early 2019, the Global Literature in Libraries Initiative, a new non-profit founded specifically to promote translated literature, presented its first GLLI Translated YA Book Award, designed to promote worthy titles in the genre that has seen the fewest translations of all: young adult literature.

Nevertheless, despite the growing acceptance of translated literature, big challenges remain. For one thing, America still publishes far less translated children’s literature than many other advanced nations. Consultant Wischenbart found that translations made up 12% of total translations in Germany, 15% in Italy and 21% in Spain in the years 2016 or 17. More than 15% of the total books Japan published in 2016 were translations, according to Japanese Board on Books for Young People President Yumiko Sakuma.

Moreover, the international literature we do publish or distribute, is overwhelmingly from other English-speaking or writing countries, and if not, from other European countries. The CCBC’s data reveals that 72% of total children’s book translations in 2018 came from just four languages—French, German, Italian and Spanish. Only 10 books, 6%, were translations from non-European languages.

So what can we do to maintain the momentum in bringing translated children’s literature to the United States, while rectifying the gaps that have emerged?

Readers need to be made more aware of translators and translations, and more generally of the existence of all the international books around them—even if they happen to be Harry Potter. OIB’s Bindy Fleischman says that when she gives workshops and presentations, the teachers and librarians who attend often tell her, ‘why didn’t I know about these books?’ Not only do they not know of many of the books, Fleischman says, but they do not realize that many of the ones they did know were international.

For that reason, translators should be identified on book covers and in reviews, so at the very basic level, readers will know they are reading books from abroad. Sadly, many books and reviews still do not. As recently as May 2018, the New York Times omitted the name of prominent translator Antonia Lloyd-Jones in a book review until it was pointed out on social media. Lloyd-Jones is the former co-chair of the UK Translators Association, whose work was shortlisted for the 2019 Man Booker International Prize.

In order to raise the profile of world literature in English, the major US prizes in children’s literature—the Caldecott and Newbery Medals— should consider making non-Americans eligible for consideration, like the National Book Award for Translated Literature and the Man Booker Prize in the UK. The Caldecott and Newbery receive far greater recognition among parents, teachers and librarians, than any other awards for children’s literature in the United States and provide the greatest sales incentive for publishers. Imagine the impact if a translated book were to win one of those awards.1

Adam Freudenheim, publisher of Pushkin Press, attributes recent growth of adult translated literature, at least in part, to “the Ferrante effect [the wildly successful international publication of Elena Ferrante’s Neopolitan Quartet, translated by Ann Goldstein] – it’s hard to think of a bigger international literary phenomenon of the last few years… But there’s been nothing like this growth in children’s literature and perhaps it’s in part because we’re still waiting for a Ferrante moment or a major, international prize like the Booker for children’s literature.”

As mentioned above, the Batchelder Award has taken steps to broaden its scope to attract more titles. The summary of the 2018 Batchelder Award Evolution Task Force noted that “the impact of the Batchelder award to date is not tremendously significant if measured quantitatively. The number of books considered by the committee each year continues to be modest.” Accordingly, it could attract greater attention if it awarded the translator and author instead of the publisher (a point raised by a number of respondents to the task force’s questionnaire – Batchelder Evolution Summaries, 2018). Doing so might boost the visibility of the author and translator, and therefore ultimately the potential audience for a book, much as it does for the Caldecott and the Newbery.

Finally, and arguably most importantly, we need to encourage the translation and distribution of books from less-translated languages, any language other than French, German and Spanish, that is. We are stuck in a negative cycle, in which there are not enough translations of children’s literature from such languages because there are not enough translators, and there are not enough translators because there is not enough work for them, according to Avery Fischer Udagawa, international translator coordinator for the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators.

But even Spanish-language translations from our neighbors in Latin America do not get into the United States in great numbers, despite the immigrant presence from those countries. Says Ellen Myrick:

“There are so many things at Bologna that have not come over here yet. I’d love to see more from South America here in the US. I think there are a few publishers that do South America very well, but not many. And, oh my God, there’s some amazing publishing being done there!”

***

Librarians, academics, and teachers widely agree that reading books from around the world is critically important for children. In an age of increased diversity in our neighborhoods and schools, and when xenophobia is on the rise at home and around the world, it is ever more important for children to be able to develop empathy for others, through books.

“The best books break down borders,” wrote Hazel Rochman. “They surprise us— whether they are set close to home or abroad. They change our view of ourselves; they extend that phrase ‘like me’ to include what we thought was foreign and strange.”

That is especially true of translated books, since they are written in a different language and written for a different audience and with different cultural assumptions. “What I think is really key is that what the Outstanding International Books list represents,” says Bindy Fleischman. “To read a book that was published in other countries for other children and find relatable stories is just so much more authentic.”

ENDNOTE

1There was a big hoopla following the translation of Cornelia Funke’s The Thief Lord, which won the Batchelder Award in 2003 and stayed on The New York Times bestseller list for 25 weeks. Since then, more than 30 of her works have been translated into English.

David Jacobson a member of the board of the Global Literature in Libraries Initiative and on the committee for the 2020 GLLI Translated YA Book Prize. He is also author of Are You an Echo? The Lost Poetry of Misuzu Kaneko.

Filed under: Guest Posts

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

One Star Review, Guess Who? (#202)

Exclusive: Giant Magical Otters Invade New Hex Vet Graphic Novel | News

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

Take Five: LGBTQIA+ Middle Grade Novels

ADVERTISEMENT

Betsy — thank you for giving this space to international books; David, you are just back from the International Youth Library in Munich — eager to hear more from you.

I can’t wait to see which books the HCA folks will bring to our attention.

Tim Ditlow and Tucker Stone just ran a panel at USBBY in which we spoke about the state of international books for youth, and translated book here in the US. As David mentioned there are some signs of optimism.

I would love to see the count of translated books received at the Cooperative Children’s Book Center posted yearly as part of the annual diversity statistics.

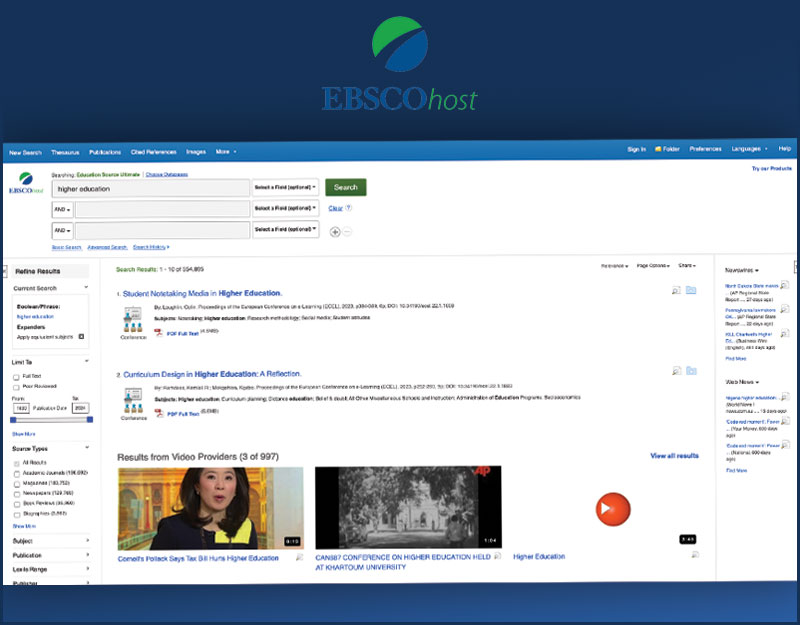

The CCBC has been great about responding to requests for their translated book logs, which I used to create the chart above. The logs in full may be needed for digging into such issues as source language diversity, but the overall count is useful for—among other things—comparing the percentage of U.S. children’s books that are translations, with the percentage for other countries.

African countries such as South Africa’s children’s literature is virtually ignored which I find a tremendous pity.

I think I can say with certainty that I have never seen a South African book published in the U.S. Is not that odd?

Betsy:

I’m not so sure about that. Beverly Naidoo, Mark Mathabane — books from SA authors, and more to the point, Catalyst Press is starting to bring us new titles from Africa: https://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/industry-news/publisher-news/article/72917-catalyst-press-debuts-with-four-titles-from-africa.html

Jessica was at the USBBY event in Austin.

Excellent. It is a point I would hope to be proven wrong about.

I just noticed this translation from Afrikaans among the nominations for the UK’s 2020 Carnegie Medal: https://oneworld-publications.com/a-good-night-for-shooting-zombies-pb.html

Thank you, Betsy, for offering me this opportunity, and to you all for your interest and comments. I think Avery’s suggestion is a very good one, and it would send a message that we in the US need to develop empathy and understanding not only for those at home, but for those all around the world. At a time when our own politics turns on events in Ukraine, Russia and Syria, among other places, such cross-cultural understanding could not be more necessary.

And Miemie, I second your suggestion that we need more books from South Africa, if not the entire continent of Africa. A few years ago, I suggested a list of international books to the Seattle Public Library for its annual “Global Reading Challenge.” That’s a city-wide book trivia contest for 4th and 5th graders, based on a pool of books chosen by the library. Ironically, though, few of the books chosen over past years have been written by authors from outside the U.S. The only one I found from Africa (South Africa, in this case) that fit the criteria was “A Good Day for Climbing Trees”, by Jaco Jacobs.

Incidentally, the reason the event is called “Global” is because at some time in the past, schools from British Columbia, Canada, also participated.