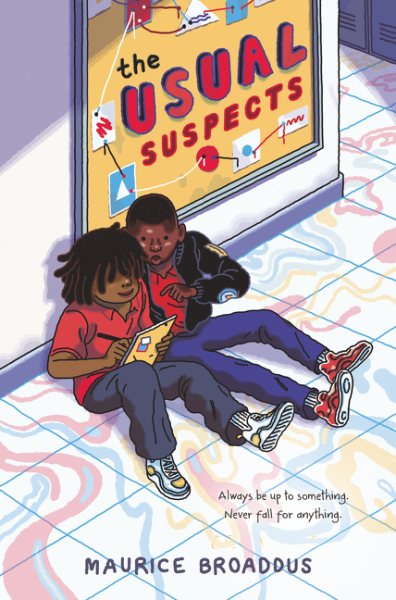

Review of the Day: The Usual Suspects by Maurice Broaddus

- The Usual Suspects

- By Maurice Broaddus

- Katherine Tegen Books (an imprint of Harper Collins)

- $16.99

- ISBN: 9780062796318

- Ages 9-12

- On shelves now

Have you ever felt deep down bone mad at the universe because it withheld information from you? Information that is, by rights, yours to have? Because at this moment I’m in that very situation. I have here, in my hands, a book. I have read this book and found it marvelous. So I am in this funny state where I’m overwhelmed with love for this wonderful book on the one hand, and engulfed in a red hot fury that more people don’t know about it on the other. Some people discover a great book and they feel this sense of satisfaction, like they’ve discovered a gem or a treasure that is theirs and theirs alone. That’s not me. When I discover a great book my first thought is whether or not enough people are singing its praises. The Usual Suspects by Maurice Broaddus isn’t doing too terribly in that department so far. It’s received starred reviews, sure it has. But that’s not good enough, people. I want buzz. I want this book, so full of wit and intelligence, raw honesty and clever plotting, to be so well known that when I say “The Usual Suspects” to a room of librarians, their first thoughts involve neither Casablanca or Keyser Soze but this work by Maurice Broaddus. This all-too-real book.

You know that special ed class where a school will toss all the kids they don’t really want to deal with? It’s a room of troublemakers. A room of scapegoats. A room ruled by Thelonius Mitchell. With a brain that’s always working, Thelonius sees through every person he comes across, working the angles, figuring out their weaknesses. Then, one day, he finds himself in a precarious position. A gun has been found on school grounds and by dint of being the usual suspects, the special ed kids are now under close scrutiny. Thelonius is used to the world thinking the worst of him, but this is a whole other level of injustice. It’s enough to get him investigating on his own. But as he begins questioning the different factions and kids of the school, it becomes clear that there are forces at work here that would like nothing better than for him to drop the whole case. And they’re willing to go to some pretty far lengths to make sure he knows exactly who’s in charge.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

In 2019, the year of this book’s publication, middle grade fiction has made a huge shift away from the fantasy novels and apocalyptic fiction of the Harry Potter and Hunger Games era. As any news channel will tell you, confrontations with reality yield far more drama than any dragon or bleak future could muster. In response, I’ve seen author after author attempt to render the times in which we live into palatable fiction for young readers. The best amongst them respect the kids. They know that children see far more than we ever give them credit for. The worst come off as preachy pablum, trying to instill lessons in great inelegant chunks. Many of these books tackle the topic of systematic oppression and racial inequities, both historical and ongoing. Some will talk about the police and others about protests and taking a stand. At first glance, The Usual Suspects wouldn’t strike you as one of these books. It’s fun, witty, and bouncy at times. Yet when you scratch even lightly at the surface, you see how Maurice Broaddus is doing something better than telling. He’s showing. Time and again, Thelonius outlines what it is like to live in a system where you’ve been labeled as a bad kid from the get-go. Constantly facing accusations and inequities, he’s shut down internally. Once in a while he’ll allow himself to have a dream for his future, but most of the time his head is full of the messages he’s been handed. His saving grace is that he can see outside himself a little. He says, “Stories are all about how they are read, not the teller’s intent. Sometimes the intent and the meaning match up, but sometimes they don’t. It’s easy to let a bad story get in you and define you. To let that version of how people see you soak in and take root, growing inside you until you find yourself becoming and acting out that story. It’s one reason I’m as suspicious of ‘teachers’ as they are of me.” And by putting you in T’s head, that oppression is more tangible than a million books that merely talk about oppression. Broaddus has just put it in terms you can understand with people a lot of kids see every day but don’t see, if you get my meaning. By giving voice to the voiceless, he’s redefining what it is to be a middle grade novel about systematic racism.

They will tell you that folks that like Jason Reynolds or Sharon Draper would like this book. I have no idea why they say this. I mean, I know why, but Maurice Broaddus doesn’t write a thing like either of them. I saw someone online compare it to Maniac Magee which rubs me the wrong way entirely. You know what I thought of when I read this book? I thought of Harriet the Spy. Not the cutesy version people who haven’t read it in 20+ years remember, but the actual book. The one about the kid who’s smarter than most of the people around her, but self-sabotages herself every step of the way. When I read this book I also thought of the movie Brick, in which a kid conducts a thorough investigation, but must wrangle with various factions at school that want to stop his detective work cold. But the thing I thought about most is actually mentioned within the book itself. At one point Thelonius says, “Moms got me into reading Walter Mosley’s Easy Rawlins books.” Now I have lived a long time, but I’ve never seen a middle grade author make a pass at replicating Mosley for younger readers. What we seem to have here is something entirely new.

Let’s talk compelling characters. Which is to say, let’s talk Thelonius himself. Written in the first person, he’s not a cipher but nor is he a Nick Carraway, commenting on people more interesting than himself all day long. One of the problems I often detect in first person narratives is that the main character just doesn’t have that interesting an interior life. Not a problem here. Thelonius just brims with insights, smart takes, and a jaded outlook on the adults around him. Broaddus continually peppers the book with off-handed comments that drill down deep into his main character’s core. Take when Thelonius is on the basketball court. When he has the ball, he’s a hog. And when he’s called out on this he says, “When the ball isn’t in my hands, when I’m not in control, I’m helpless. I can run around all I want, make screens, confuse the defense, but the reality is that whoever has the ball determines the action.” Look at the seeming effortlessness of that statement. There’s an elegance to the writing here. The author is trusting that the young reader will read more into that statement than what appears on the surface. That’s what I mean when I say he treats his readers with respect. Like they have brains or something.

And Thelonius, while we’re talking about him, is himself limited. He’s interesting because you sometimes have a hard time rectifying his actions with his interior monologue. You like this kid pretty early on. Broaddus should probably give seminars on writing likeable flawed characters. At the same time you (and I think child readers would feel this as much as adult) are frustrated that he’s squandering his talents on various pranks. By the end of the book you get a glimmer of a sense that he might find a way to break out of his own self-imposed limitations, but clearly a sequel (hint hint hint hint) would be of use here. At one point he says, “I’m trying to do better, but I’m not sure what better looks like just yet. I think of it as using my powers for good against a bad guy. I may need to work on developing new powers, but until then, I’m going with what I know.”

Of course, to get at the other characters in this book you have to go through Thelonius’s lens, and there’s a danger to that. If he’s too insightful then he starts sounding like an adult and you don’t trust your narrator’s voice. So the author has to walk this line between Thelonius’s deep-seated intelligence about his fellows, and the limitations of his own (admittedly magnificent) brain. Broaddus, once again, solves much of this with descriptions that say more than they say. Of Nehemiah it says, “Compared to him, I’m sculpted like an Olympian. He seems built like a collection of angry twigs.” Rodrigo Luis, “has the body of a third grader who had a diet of only leaves and water.” A particularly nasty character’s smile, “was ugly and jagged, like someone took a broken bottle and carved a slit where a mouth should be.” Tellingly, Thelonius is best at understanding people when they’re young. Adults throw him for more of a curve. He can’t separate their actions and intentions from the system they’ve signed on to and it makes him permanently skeptical of their actions. He loves his mom (who is a powerhouse of a woman that probably deserves a book of her own) but anyone in his school or associated with his school is immediately on watch in his eyes.

We all have our preferences in the books we read. My preference is towards middle grade novels filled with sentences that pop off the page and dance around for a while. Honestly, you could not have constructed in a lab a book as jam packed with sentences more delicious than the ones found here. Some of my favorite examples:

– When Thelonius’s mom gets off the phone with Nehemiah’s mom or grandma, “After a few minutes on the line with them, she stared at our phone like it was an alien tongue trying to lick her.”

– Nehemiah’s grandma, “wears misery for makeup and chugs bitterness for vitamins.”

– Of a fellow student, “his hair is a series of short dreds in need of tightening that stand nearly straight up so it looks like he’s wearing a fallen crown.”

– “Nehemiah bounces his Teddy Grahams package off my chest. He hates them because he ‘never trusts anything that smiles all the time’.”

– “That girl can’t find a maternal bone in a cemetery of mothers.”

At one point in the book Thelonius talks about the difference between himself and the kids that are beloved by the teachers. The ones that obey all the rules without question. He says, “they’re always going to fit in. Nothing wrong with that. We just come at the world different because it comes at us different. It comes hard, we go hard. We don’t fit in with how the system wants to define us and sometimes we have to turn the system on itself for us to get by.” Even the adults that want to help are held back by this same system, and in many ways it’s the small changes Thelonius makes at the end, and not the solution to the mystery, that’s the real success. You want to know the real reason I compare this book to Harriet the Spy? Because it feels like the author is handing truths to the kids reading it, completely bypassing the adults of the world. It feels sneaky. I can see a kid gleaming truths from these pages that they have NEVER encountered anywhere, with the possible exception of their own brains. I can see adults becoming uncomfortable with just how much honesty is on display here. It gives away the game, this book does. It’s always a good idea to sometimes read a book that’s smarter than you are, starring a kid that’s smarter than the world around him. You know why I haven’t heard more people talking about this book? Because nobody knows how to sell it. Well, sorry folks, but the secret is out now. It’s one of the best books I’ve ever read for kids, and maybe the best school rated children’s novel I’ve encountered period. This, right here, is the book of our times.

On shelves now.

Source: Galley sent from publisher for review.

Filed under: Best Books, Best Books of 2019, Reviews, Reviews 2019

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

One Star Review, Guess Who? (#202)

More Geronimo Stilton Graphic Novels Coming from Papercutz | News

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

Take Five: LGBTQIA+ Middle Grade Novels

ADVERTISEMENT

I must read this book. I have been thinking of Harriet the Spy lately because she never toed the line. When her spying came to light, she did not buckle – even though I so wanted her to say, “Oops, sorry. My bad!” Can you even imagine Harriet saying that? Now, I have to re-read THAT book, too.

I had a really good feeling about this book. Extra glad that we got three copies for our school library and I can’t wait to read it myself!

YES!!! I’m so glad you spotlighted this one. It’s so, so deserving. I’m not sure I’ve ever read a middle-grade that respects its readers more, like you say. I’m afraid that the cover, among other marketing-ish things, didn’t help garner interest (possibly the opposite). And I’m really scared Mr. Broaddus won’t return to middle-grade as a result 🙁

A fear I share. So let’s do what we can to get the word out. I have ideas . . .

Oh. This book made me cry. I read it because of your impassioned review. And I do not disagree with you. If read by adults this book is everything you say it is. But the ending, especially, made my shoulders slump in defeat. This is not the world I want children to grow up in. BUT it is the world that they grow up in. And that makes me just drop my head into my hands.

Thelonius’ solution was clever and his sense of victory understandable, but it was also unfair. The character he targeted was a needy character, too. But what else could he do???? I have to keep telling myself that it’s FICTION! And maybe it will help the kids who read it negotiate an increasingly treacherous childhood.

I saw a glimmer of hope at the end of the book, if only because Thelonius shows a great deal of personal growth in the course of the storytelling. But I agree with you that the solution to his problem is problematic in and of itself. It almost comes down to the needs of the many outweighing the needs of the few. This would probably be the best book club book you could come up with. There is so much here.