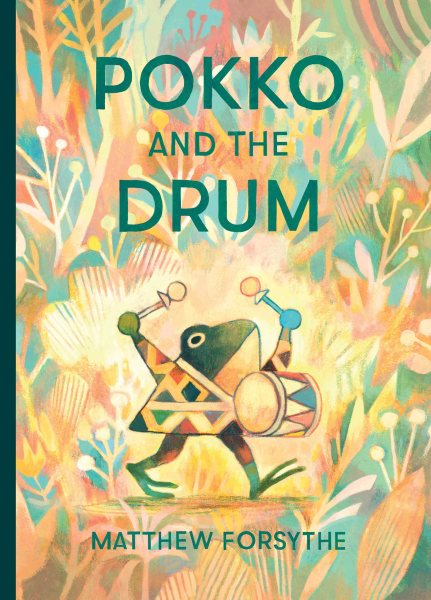

Review of the Day: Pokko and the Drum by Matthew Forsythe

- Pokko and the Drum

- By Matthew Forsythe

- Paula Wiseman Books (an imprint of Simon & Schuster)

- $17.99

- ISBN: 9781481480406

- Ages 4-7

- On shelves October 1st

Matthew Forsythe did not attend art school. Ask him where he learned his stuff and he’ll recommend that you read High Focus Drawing by James McMullen. He’s worked on picture books before, lots of them, but until now he’s never written and illustrated one himself.

Matthew Forsythe has been holding out on us.

Every once in a while I encounter a picture book that gives me so much to chew on that I have to put it down for a while and come back to it after a few weeks. The theory is that when I do this all the little bits and pieces will fall into place and make sense to me. However, when I came back to Pokko and the Drum I found that here was a picture book that required multiple rereadings. There’s something going on in this book. A wry, whipsmart, funny tale that actually may have a thing or two to say about female empowerment. Or not? It’s easy to read too much into this book, but I’d say it’s also just as easy to read into it everything that you need it to be. Intelligent writing for kids that will not just appeal but engage and entice. This, we need more of.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

It’s not that Pokko’s parents haven’t screwed up before. They’re a kindly frog couple but when it comes to giving gifts they have an odd tendency to hand their daughter presents that may not always be appropriate. This time, they’ve given her a drum. Pokko likes her drum. She likes to play it. She likes to play it so much that one day her father has her go outside to play, but softly. Pokko goes, but soon her drumming (which is not soft) attracts a crowd of musical followers. The crazy thing about Pokko and her drumming? She’s really good! And even her dad and mom will have to come around to that fact, one way or another.

Every summer I teach a six-month writing class to teens at my library and one of the topics I always make sure to cover is the opening sentence. In a book of any sort, whether it’s a YA novel or a comic, that first sentence should be carefully considered. To prove my point I’ll wheel in a big truck of advanced reader galleys of young adult titles and we’ll have fun comparing and contrasting their first sentences. But until I read Pokko and the Drum I’d never seriously considered the possibility of looking at the first sentences of picture books as well. Yet the first sentence of a picture book is, in many ways, of even greater importance than that of a novel because in a book that’s only 32, 40, or even 64 pages, every word counts. That’s why it’s such a delight to open Pokko and find yourself greeted by, “The biggest mistake Pokko’s parents ever made was giving her a drum,” followed by, “They had made mistakes before.” It sets the tone for the entire book. A tone that, happily, is matched by the art, step by step, blow by blow.

Matthew Forsythe is Canadian by all accounts. He has, however, worked in Dublin, London, Seoul, and L.A. And, in a bit news that snaggled my brain good and hard, he apparently was the lead designer on the Cartoon Network’s much lauded show Adventure Time. Of all the facts that I have written here, perhaps that one is the most pertinent to Pokko. You see, there is a sensibility to this book that causes it to stand apart from the massive pack of picture books published in a given year. It’s hard to pinpoint, but if I had to give a name to it I’d have to say that the book feels like it was steeped in wry, British humor, pacing, and timing. The jokes, which land every time, are often of a visual nature. It is funny to see a small frog on a llama. It is funnier to eventually notice that the llama is lying on two pairs of frog legs, evidently squished beneath. Humor that works in such a way that both kids and parents get it and love it is exceedingly difficult to attain. This book does it so easily, it feels like it’s not even trying that hard.

The book has a beautiful mastery of deadpan that should probably be studied by future generations on how to do it right. First off, let’s examine Pokko herself. Forsythe has summarily rejected the Arnold Lobel method of froggy eyeballs and given his heroine round rather than horizontal pupils. He has also given her a face that remains almost expressionless throughout the story. I say “almost” because at critical moments there are two things that can occur when Forsythe zeroes in on a frog’s face. The first time that this happens is when we learn that the forest Pokko walks through is quiet. “Too quiet”. Suddenly the image that fills the page is Pokko’s face in close-up, her eyelids half-closed in a look of, not fear, but some kind of skeptical breakdown of the fourth wall. She’s clearly looking right at the reader and saying, on some level, “Oh, please.” The second time we get a similar close-up it happens with Pokko’s father. He hears the music outside growing louder. “And louder”. Compare this shot of the father in the second shot to the first. Do you see the difference? It’s subtle but Forsythe has taken what appears to be a black colored pencil and swiped a bag under the father’s eye. That single, solitary line says more than a page of words ever could. One little swipe. A world of sorrow.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

For all that the humor feels very contemporary, there are some ancient tropes at work on these pages. Consider the fact that the inciting incident in this book is that Pokko enters the woods. The woods, traditionally (as Stephen Sondheim would be the first to tell you), are where the darkness and danger lie in wait for you. When your hero is warned of something, as Pokko is warned not to play her drum loudly outside because “we don’t like drawing attention to ourselves”, and that warning is disregarded, you expect punishment. And woodlands are good places to dole out such punishments. So without so much as hinting at a villain or antagonist, Forsythe is using kids’ innate understanding of storytelling rules to heighten the tension.

But let me just stop a moment here and let you in on something else that I’ve noticed about this book. After an initial read I liked it very much but I found myself vaguely wondering, “But what is it really about?” If it wasn’t about anything, why did I like it so much? So I went back to it and examined it a little more closely. Pokko is a female frog, first off. She enjoys making a lot of noise. Her father urges her to go outside but to be quiet. So the female child does so, but soon she makes a big ruckus. When she does so she inadvertently becomes a leader. Other animals follow her. Making music, sure, but following just the same. Now look at what happens when the wolf, who is following in the back, eats the rabbit playing the trumpet. Instantly, Pokko is having none of that. My daughter, who is eight, wondered why the wolf’s appetite was placed in the book at all and my initial thinking was that it was just there to be cheeky. But then I took a closer look and saw that here you have a female character leading. One of her followers acts inappropriately and instead of ignoring it or shying away, she confronts it dead on and reads it the riot act. “No more eating band members or you’re out of the band.” Because, you see, Pokko knows perfectly well that a follower that eats your other followers may just be biding its time until it bites at you as well. The end of the book finishes with her parents being swept along with the others and her father, who initially told her to be a good quiet girl, realizing that she’s really good at what she does. Now I don’t want to say that Forsythe wrote this with the intention of making some kind of commentary on girl leaders, but I’m not not saying it either. In this book, the frog persists.

Is it odd that I keep looking at Forsythe’s art, trying desperately to find somewhere between the lines an explanation of why his style works as well as it does? I’ve read interviews with him and letters of advice he’s given to other artists. It doesn’t help much. So I try reading the words that other reviewers have written about him, but they appear to be just as stumped as I am. They call his art “glowing” evoking “lush elegance” and that his images are “tapestrylike”. The word that comes closest to what I want to say is that overused term “luminous” which is close but not quite right. “Luminous” implies gentleness, but what Forsythe is wielding here isn’t gentle. Or, at the very least, it isn’t ignorant of that skinny sliver of darkness that underlies even the sunniest day.

After reading this book to my kids, I tried to explain to my daughter why I liked it so much. “I like it when authors take risks.” Well, what did I mean by that? “I mean . . . a lot of what the author (who is also the artist) is doing here isn’t … safe, I guess. This book doesn’t go in a predictable direction. It doesn’t assume you know where it’s going to end and make you feel good by fulfilling that expectation.” She didn’t know what I meant and, frankly, maybe I didn’t either. All I know is that this is a book that leaves wide open the very real potential for tragedy, but instead ends up making its heroine stronger than ever. “And you know what?” her father says at the end of her book. “I think she’s pretty good.” I think this book is pretty good. And I think all the kids who read it will think it’s pretty darn good too.

On shelves October 1st.

Source: Final copy sent for review.

Filed under: Best Books, Best Books of 2019, Reviews, Reviews 2019

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

The Moral Dilemma of THE MONSTER AT THE END OF THIS BOOK

K is in Trouble | Review

Fighting Public School Book Bans with the Civil Rights Act

ADVERTISEMENT

I think what I like best about this post, in addition to the fact that it brings attention to a wonderful book, is the kind of meta-discussion of how to write about illustration. Sometimes one feels “stumped,” as you put it, not wanting to resort to the same string of adjectives. I’m sure that other reviewers have confronted the same problem in trying to do justice to exceptional picture book artists.

Not to keep beating the same drum note, but I have commented before about Debbi Michiko Florence’s work. In “Jasmine Toguchi, Drummer Girl,” which is not a picture book, but an illustrated chapter book, Jasmine is a little girl who plays the traditional taiko drums of her culture. At first she is hesitant, but later confident. Unlike Pokko’s parents, Jasmine’s are one hundred percent supportive from the start. Different artist, different genre, but same emphasis on female authority within tradition.

Oh, lord, I’m loving this book and your analysis. And I’m flummoxed by the artwork as well, especially the spread of Pokko going nose to nose with the wolf. Those empty eyes! So chilling. And Pokko, so steadfast. But apparently the wolf meant it! There’s too much authority in the narration to doubt it, I think. And there’s so much to examine throughout, ai yai yai.

Mmm. I love how you put that. “There’s too much authority in the narration to doubt it.” I may have to steal that line.

I can hardly wait to get my hands on this book. I love how Mathew Forsythe’s artwork is so luminous. Do you know if this title qualifies for a Caldecott?

Alas, it does not. The man is Canadian. But, if someone could please encourage him to move to the States in the next (checks watch) four months, I would be grateful.