When Kyle wrote Aidan: Process and the Trans Child Narrative

The words “important” and “good” are not synonyms. Just because a book is important and fills a need, that doesn’t guarantee that the book is any good. Now we find ourselves in an era where we see a vast increase in “important” books. Books that give voice to groups historically marginalized in the past. Authors and illustrators that might never have been given a chance to write or illustrate picture books for children, if not for the times in which we live. This is a great good thing, and, like all picture books, some of these books are amazing, some of them are okay, and some of them are truly terrible.

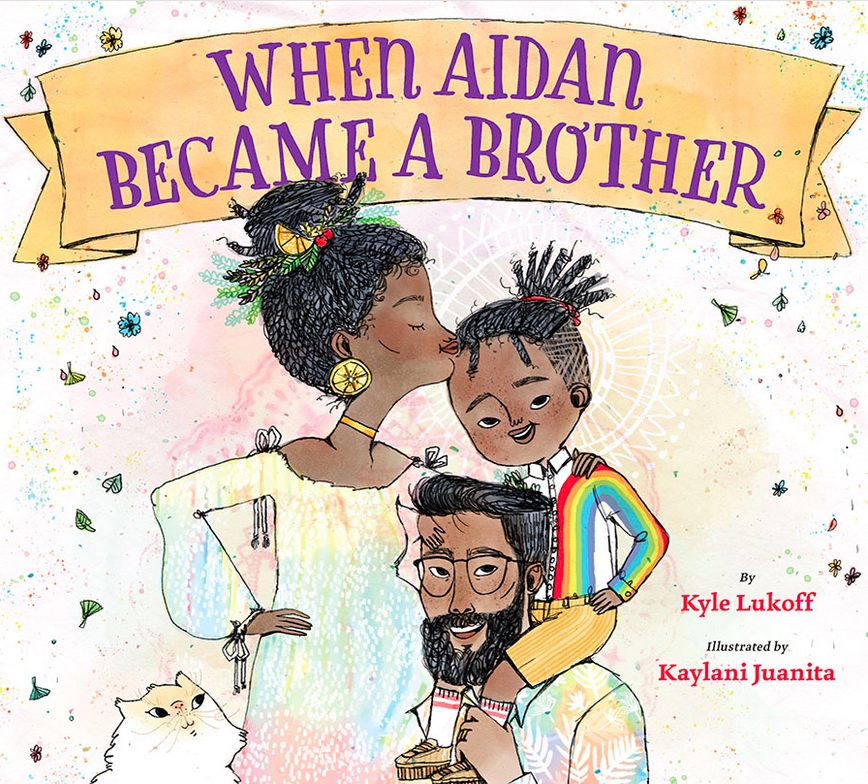

There is no denying that the book When Aidan Became a Brother by Kyle Lukoff, illustrated by Kaylani Juanita is an “important” book. In it, a young trans boy frets about his mom’s upcoming baby and whether he will be able to “get everything right” when everything was once so wrong for him. The thing about this book is that there’s more to it than just its message. Lukoff’s writing here excels. The art is marvelous and the story utilizes so many different picture book techniques that it could be easy to be blinded to the elegance of the prose in the face of the subject matter.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Now I’ve known Kyle for years. We were librarians in NYC back in the day, so when he proposed this interview, one with a focus on the writing in the book, I felt palpable relief. You know that feeling you get when a friend writes a book and you read it and discover it’s not that great? Not a problem here. Aidan is a wonderful title and I invite you to discover why:

Betsy Bird: So I have this theory that when people first try to introduce a human right to kids in some way they tend to follow a pretty standard format. The book will place the idea, like a kid being trans, front and center in the narrative, and just sort of forget about including character development above and beyond that person’s identity. Like the identity equates personality. Now, you’re a children’s librarian. You’ve probably seen a wide variety of books out there, and AIDAN actually gives its main character depth. Was that something you were going for from the start?

Kyle Lukoff: Yes, totally. Your theory holds water with a lot of books, and if there is any kind of character development, it’s basically Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer: marginalization, then some inciting incident that leads to uncomplicated peer acceptance. I resisted writing a trans picture book for a long time because I’ve slowly developed an aversion to those kinds of narratives, but couldn’t figure out how to break away from them. But this story is backgrounded by my experiences within trans community, with my librarian career playing more of a supporting role. I first came out as trans fifteen-ish years ago, and have been lucky enough to form complex relationships within a heavily queer and trans network. So Aidan’s character grows out of the depth and breadth I’ve seen in my community, rather than some cursory notion of what a singular trans identity or experience looks like.

Betsy: For the record, that Rudolph comparison is dead on, since that “uncomplicated peer acceptance” always drove me batty as a kid. Plus the fact that Rudolph never takes revenge. I was an odd child. Part of what I like about your book is that there’s no “society as villain” element to it. You have nice, well-meaning, adults saying the wrong things, which is such a day-to-day occurrence that any kid could relate to. There’s no bully. No evil person representing a larger whole. Why the reality check?

Kyle: So many reasons that I could probably write an entire essay on the topic (ooh maybe I should!). One reason is because I’ve really started to question whether that Rudolph narrative is effective. Or useful. Enough generations of children have absorbed that basic plot that if it was going to do anything to stop bullying or oppression, it would have worked by now! But no one wants to see themselves as one of the jerk reindeers, except we’re all jerk reindeers AND misfit toys at the same time.

Another reason is that we all know that books can reflect the world we live in, and they can also aspire towards the world we want to live in. Yes, putting Aidan through some kind of transphobia, from family and peers, wouldn’t be unrealistic. But I wanted to model other possibilities; that when your kid comes out as trans you can kiss them on the cheek, and tell them you love them. That one way to respond to having a trans child is to find them support, and help them make friends with other trans kids. It seems utopian, but it’s entirely within our control. Hopefully, though, the emotional depth of the story shows that trans kids (trans people) have interior lives and landscapes that are intertwined with our identities but not always just reactions to explicit oppression or transphobia. You can love trans kids (and any kid) as well as you possibly can, and they are still going to get hurt. That’s just part of being a person.

Betsy: For the record, I’m stealing that line, “we’re all jerk reindeers AND misfit toys at the same time.”

Now this isn’t your first picture book, but it’s the first one I’ve seen you create that had a plot. Now if I walk into my library I can find shelves and shelves and shelves dedicated to the notion of how to plot a novel. Plotting a picture book is taught more in workshops and the like. What was your process in putting this storyline together?

Kyle: It was hard! I’ve never taken classes or anything in writing for kids–reading many hundreds of picture books, good and bad, was most of my education.

The first draft of what eventually became AIDAN was a brainstorm on a day that I stayed home sick from work. I wrote the first few pages in between making breakfast, and finished it that morning–and, actually, if you’re curious about what that draft looked like, keep an eye out for CALL ME MAX, an early reader I have coming out from Reycraft Books this fall, adapted from that original. The second draft came after working with an agent and an editor, and it was kind of a disaster, but you can see the seeds of AIDAN in it. After that failed I was sitting in the Rose Reading Room at the main branch of NYPL, trying to figure out how to tell this frickin’ story. I thought to myself, “Well, when Aidan was born, everyone thought he was a girl,” and then realized that was the perfect first sentence

I don’t want to sound absurdly pretentious, but you know that famous quote about Michelangelo sculpting David, how he just chipped off the bits that didn’t look like David? That’s what writing this draft felt like. I suddenly understood the whole story, and shrugged off all those other efforts like an old cardigan. My editor at Lee & Low, Cheryl Klein, worked hard with me to create the final version, but the book you’ll be reading came directly out of the story I wrote that afternoon

Betsy: You’ve just mentioned two things I love: The Rose Reading Room and Cheryl Klein. Let’s talk editor. How did she walk you through the rewrites? Phone conversations or comments within the document? Long letters? And how did those conversations strike you?

Kyle: Working with Cheryl is an incredible experience. We spent a lot of time debating about single words; “date” or “day,” “if” or “when,” “felt” or “thought.” Because when a story is under a thousand words, every single one of those words has to be as perfect as possible

Since I live in New York, I was lucky enough to be able to meet with Cheryl, at a coffee shop not far from the Lee & Low offices. We discussed the story a few times in person, but the bulk of the edits took place over email, or with comments in a document, that ended up turning into lengthy discourses about trans identities and literature in and of themselves.

One element that made that process challenging but rewarding was knowing that Cheryl is profoundly brilliant, with a mind for text that operates on a level I can’t even fathom. But also, I’m trans, and Cheryl isn’t, so we were discussing how to represent Aidan and his family, and the central question of what the story is about, long into the editing process, because we were coming to it from such different places. Even realizing that we had somewhat divergent interpretations took awhile to become clear, since I thought “of course this is what the story is about” and Cheryl was like “of course this is what the story is about” and turns out we were thinking about different stories. There were moments when I thought, somewhat petulantly, “OBVIOUSLY this is what I’m saying,” but I also knew that if Cheryl’s read of it was different from what I intended, it was incumbent upon me to maintain the integrity of the story I was trying to tell, while also making certain that that vision came through for all readers, not just those who are embedded in queer and trans politics and community. Luckily I love revisions, especially when so well guided, so it was a really fun process for me.

Betsy: Oh, dear god. I’m going to forget you just said you love revisions. Now, there’s a nice use of callbacks and repetition in the text. It’s the kind of thing that a reader might not notice consciously, but enjoy without quite realizing it. Were you looking to specific picture books for inspiration in this respect? Or did that just come naturally as you were writing?

Kyle: I have to thank Michelle Knudsen for that. I’ve cared about the art of the picture book for years and years, but never consciously thought about or dissected what one needed to be successful. Her book BIG MEAN MIKE was the first picture book that really opened my eyes to the need for structure, how the entire story revolved around one bunny, then two bunnies, then three bunnies, and then FOUR BUNNIES, as a way of exploring hugely complex ideas around masculinity and identity. After reading that book a dozen times I started looking really closely at how picture book authors tightly construct scaffolding for kids to organize their thinking around

So when I wrote that first page of AIDAN, I hit on three points: his name, his room, and his clothes. And those three points, in that order–name, room, clothes–show up consistently as Aidan is transitioning. Then when the baby enters the picture, the three points invert, and we learn about the baby’s clothes, room, and name, and then Aidan’s anxieties revolve around the clothes, room, and name, keeping that order intact. It’s something that readers might not notice consciously unless they’re looking for it, but is crucial for making the story feel like a picture book instead of a truncated short story.

I could say it came “naturally,” if you think of a constant conscious and subconscious analysis of structure “natural.” It’s also related to my innate pull towards formalist poetry, like villanelles and sestinas, art with repeating language that pushes the meaning forward

Betsy: Huh. Poetry as form. So would it be fair to say that as an author you’re drawn to structure? This leads me to assume that when you’re writing you plan everything out beforehand (say, in a Rose Reading Room) rather than let the story come to fruition as you go. Is that correct? And, if so, how do you feel that influences your creativity?

Kyle: Someday I will need to come up with an answer to the question “How do you write” that isn’t “I don’t know I just…do it?” I can’t tell you for sure that this is how the process works for me, but what I might do is start to work on something, and let it flow organically without trying to force any particular structure onto it. And then that draft reveals some rudimentary structure within it, which I can then tighten and refine with more intention behind it. I cannot promise that I did that with AIDAN! I think I did? It would make sense if that was my process? But I’m not completely sure. I know that I’m an outliner, but only with fairly broad strokes, and that stories also often reveal themselves as I’m going in ways that seem too good to be spontaneous. It’s all very mysterious.

Betsy: Heck, for that matter, what picture books were you thinking of when you were trying to get the structure of the story down?

Kyle: I wanted AIDAN to be like the picture books I love that feel simple but deep. The ones that say a lot by leaving space for readers to create their own meaning, while firmly but lovingly guiding you towards certain questions or ideas. WHERE THE WILD THINGS ARE feels both arrogant and obvious as a comparison, but I can’t not (and both Aidan’s and the baby’s room look, to me, like “the world all around.”) I think Suzanne Collins’s picture book THE YEAR OF THE JUNGLE affected me, as did the ways that Ruth Krause, Margaret Wise Brown, and Jon Klassen use language.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Betsy: Well, good on getting Kaylani Juanita to do the art. Did you suggest her or were you paired together? I know you might have seen her work on Kathy Ellen Davis’s TA-DA!

Kyle: I hadn’t seen it at that point, but I immediately fell in love with Kaylani’s work. I know that usually authors don’t have any say over their illustrators, but Cheryl let me express my opinion between a few options, and I knew that Kaylani would be perfect. Her style is ideal for this kind of book; that kid-friendly middle ground between photorealistic and abstract, incredible use of rich detail while still maintaining the emotional core of each scene, with so much energy and aliveness to her children. This story is as much hers as it is mine, since her interpretation brought the words alive.

Betsy: Anything in the pipeline next?

Kyle: So much! The aforementioned Max series, from Reycraft (the first one is about Max, another young trans boy, and the next two are about his adventures with two of his queer/gender diverse friends, illustrated by Luciano Lozano). A picture book that I sold before I even started writing AIDAN will be out from Groundwood next spring, that one is called EXPLOSION AT THE POEM FACTORY and it’s about a poem factory that explodes. Dactyls, flying everywhere, it’s a mess. Mark Hoffmann is illustrating that one. My agent Saba Sulaiman and I are working on a middle-grade novel, and I have four other picture book manuscripts in various stages of “I’m working on it,” but the future of all of those are big question marks. And of course I have more potential ideas than I know what to do with. Most of them are trans-related in some way, because I don’t think of cisgenderism as a particularly compelling plot device, but who knows where inspiration will strike next.

Phew! Now that’s how you answer interview questions, folks. Big time thanks to Kyle and the folks at Lee & Low for this one. And look for Aidan on June 4th. You’re not going to want to miss it.

Filed under: Interviews

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Name That LEGO Book Cover! (#53)

Exclusive: Vol. 2 of The Weirn Books Is Coming in October | News

Fighting Public School Book Bans with the Civil Rights Act

Take Five: Middle Grade Anthologies and Short Story Collections

ADVERTISEMENT

I love what Kyle had to say about the illustrations and illustrator. As I was reading this incredible post I was thinking how glad I was that you included these illustrations and how different my interest about this book might have been if they were not here. And then I read, “This story is as much hers as it is mine, since her interpretation brought the words alive.”

You and Kyle have given us much to think about today. I’m so looking forward to reading this book. Thank you both.