When Clothing Approximates Sexism (and other woes)

A friend of mine who is not particularly into the children’s literary world, except that she has small children and reads to them, forwarded on to me this recent article in Vox. It sports the clickbait title I never noticed how racist so many children’s books are until I started reading to my kids. It’s one of those pieces that sort of write themselves. Periodically we’ll see articles come out from new parents, shocked and horrified by some aspect of children’s literature. Whether its disdaining Maisy or taking issue with Knuffle Bunny, this comes up all the time. They’re sort of the easiest pieces an author can write. You’re already reading to your kids. Why not write something about the experience? I should note that even as I say this, I’ve spent a good portion of my career as a blogger doing EXACTLY THIS. So who am I to pooh-pooh other authors for doing the same? Besides, sometimes they make very interesting associations.

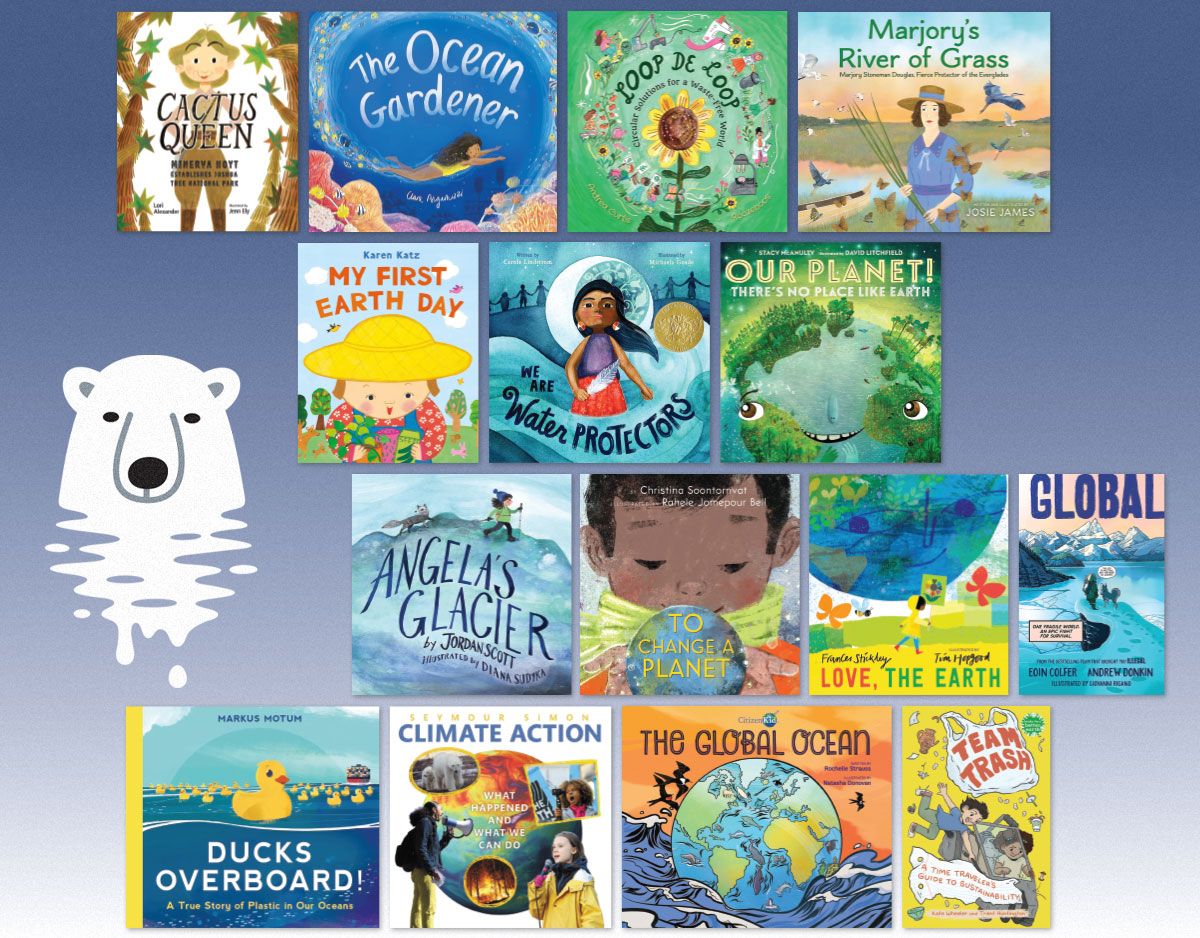

In this particular case I read the piece and found it was this curious amalgamation of good points (why yes, Little Black Sambo IS offensive!) and downright weirdness. First off, the author mentions books like The Cricket in Times Square, which is one of my favorite SURPRISE, IT’S RACIST! books out there. Folks tend to forget about it. The author of this piece, Ms. Leigh Anderson, also makes an effort to tie this into the We Need Diverse Books campaign, which is a nice idea. Essentially, the article is a call for reaching out and reading newer children’s books that have an eye towards both literary quality and diversity rather than just relying on the books you were read as a kid. I’m all for that.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Unfortunately the author of the piece effectively shoots herself in the foot when she begins to equate the existence of mothers wearing aprons in books with sexism. Several times throughout the piece she mentions a book (like Bread and Jam for Frances or Harry the Dirty Dog) and says that because the mother is wearing an apron and cooking for the other family members, the book is automatically sexist. Years ago when I worked in the Jefferson Market branch of NYPL I would get in a continual stream of grad students looking for “sexist children’s books” because they were writing various papers and needed examples. Never equating an article of clothing with sexism (my friend Erin points out that Ms. Anderson, “seems to be calling anything that isn’t feminist, sexist, which is ridiculous”) I really had to hunt and peck for these students to find anything that (A) might apply and (B) was still circulating (hat tip to Lois Lenski for helping me out on that one). Ms. Anderson, in contrast, is far too happy to throw all her childhood favorites under the bus. She writes:

“Here’s what happens when you try to recreate your 1979 childhood library: You buy Bread and Jam for Frances, Frog and Toad, Blueberries for Sal, One Morning in Maine, Heidi, The Cricket in Times Square, Lyle Lyle Crocodile, Stuart Little, Babar, Sylvester and the Magic Pebble, The Secret Garden, The Little Princess, and the whole Ramona Quimby series. All were treasured books of my childhood, read and reread to me, and then read again as soon as I could read to myself.”

She then explains the problems with some of these books but not others. Ramona’s crime, as it happens, is that “Ramona Quimby’s mother begins the series as a housewife in 1955; in the mid-’70s she goes back to work; by the mid-’80s she’s pregnant again and quits.” Because, after all, that has never happened before. The crimes of some of the other books are left for us to infer. I assume the apron problem, such as it is, applies to Blueberries for Sal (never mind that Sal is a wonderfully androgynous character that both boys and girls relate to), Lyle Lyle Crocodile (where Lyle, who is male, cooks and ice skates with the missus), and Sylvester and the Magic Pebble (anyone else remember how subversive making the cop a pig was?).

Eventually the piece becomes more about We Need Diverse Books and quotes some recent pieces about Shannon Hale’s experiences with boys and her books and the work of independent booksellers. All of which is worthy and good (though she does fail to spellcheck Whistle for Willie). As such, it’s a pity that she had to paint this piece with such a broad brush. Outright sexism did indeed exist in children’s literature in the past, but just because a book is reflecting the times in which it was written, that does not automatically make it unworthy reading.

Filed under: Uncategorized

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Kirkus, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on BlueSky at: @fuse8.bsky.social

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Band Nerd | Revieew

When Book Bans are a Form of Discrimination, What is the Path to Justice?

Writing Queer Characters with Warmth, Empathy, and Inclusive Joy, a guest post by Lauren Magaziner

Pably Cartaya visits The Yarn

ADVERTISEMENT

My cousin posted this on Facebook this morning. (http://everydayfeminism.com/2015/04/policing-womens-clothing/). There are plenty of books that show diversity in healthy ways. However, if the book is out of print of the author is considered mid-list those books no longer seem to count as relevant, a reflection of the current consciousness (but really a manipulation to sell new books).

Thank you for this article, Betsy. Sometimes we grownups just need to chill.

Oh man, Elizabeth, this is an interesting piece! It’s made me think a lot. I’m sort of surprised, though, you haven’t gotten any pushback on it. Hope you don’t mind if I do that a little bit, and maybe ask some questions at the end. You write:

“Unfortunately the author of the piece effectively shoots herself in the foot when she begins to equate the existence of mothers wearing aprons in books with sexism.”

and

“Several times throughout the piece she mentions a book (like Bread and Jam for Frances or Harry the Dirty Dog) and says that because the mother is wearing an apron and cooking for the other family members, the book is automatically sexist.”

Where in the text does she equate “mothers wearing aprons” with sexism? I’ve read her piece a few times and I can’t find a single instance where she says that! What I do find, though, are these examples couched between two sentences:

“Even the stories about families — wholesome, all-American families — I now see through a different prism.”

and

“All the mothers in the kitchen and dads in wing chairs present a fantasy world of white, four-person families, so far removed from my own only-child, single-working-mother childhood that I internalized the books (and the era’s TV shows) as normal and us as the aberration.”

Given this context, she seems more concerned with how normalized, familial depictions in older children’s books made her family feel like an oddity growing up. Rather than equating aprons with sexism, I’d argue she’s using these particular books to show why there needs to be more “mirrors” for all children, which, as you know, is a core idea of diversity.

So why the harsh dismissal? Even if I’m wrong about the familial stuff and we decide that she was providing these books merely as examples of sexism, I still feel like your characterization of her argument is a simplification, even a straw-man (your hyperbolic captions for the illustration inserts are a nice touch). It’s not just the sight of an apron she’s cringing at, but the fact that so many aprons and brooms and kitchens were the sole depiction of a mother in the home for many of these books. Are these portrayals not steeped a kind of sexism? Let’s look at a definition:

“2. behavior, conditions, or attitudes that foster stereotypes of social roles based on sex”

Do illustrations that solely depict a woman in the kitchen or holding a broom–old though they may be–foster stereotypes of social roles? If you hold to modern progressive ideals, I don’t see how you can deny that, and if you regularly use those ideals as your standard for judging the worth of a book, I don’t see how you can say Anderson’s claims are downright weird. She even says later in her piece: “by imprisoning mothers in the kitchen and fathers in the wing chairs, we’re offering young readers a limited scope for imagination.” That sounds right in line with what I hear from most arguments promoting diversity in children’s books.

Finally, you write:

“Outright sexism did indeed exist in children’s literature in the past, but just because a book is reflecting the times in which it was written, that does not automatically make it unworthy reading.”

Okay, but why is that? If Anderson’s concerns are not enough to make a book unworthy to be read, what then makes a book unworthy? That’s what I’m hoping you’ll clarify for me, if you choose to respond to my comment. You say you’re never one to equate an article of clothing with sexism (again, I think that’s a straw-man of Anderson’s argument), but do you ever equate an article of clothing with racism? And when do these things become grounds for dismissal? Do books that reflect the time in which they were written get a pass, but book written nowadays don’t? Does the passage of time somehow soften the impact of harmful stereotypes?

Finally a bit of reason. Vilifying authors for writing in the context of their time is censorship of their work. Perhaps those loudly voicing their chagrin can follow the advice I am always given: if you don’t like it, you don’t have to read it. btw I work full time and when I cook, I wear an apron. (Guys, gals, and grandkids wear one too). They are incredibly useful articles of clothing! Oh the insanity of it all!