The National Book Critics Circle or Was Lillian Gerhardt Right?

As some of you know I am currently in the process of co-writing a book for Candlewick about the true stories that lurk behind your favorite children’s books and their creators. My two co-authors (Jules Danielson from Seven Impossible Things Before Breakfast and Peter Sieruta from Collecting Children’s Books) and I have been doing painstaking research over the year, determining what tales are true, which ones are false, and which ones are true but we can’t use them until certain parties quit this sweet green earth for the choir invisible.

As some of you know I am currently in the process of co-writing a book for Candlewick about the true stories that lurk behind your favorite children’s books and their creators. My two co-authors (Jules Danielson from Seven Impossible Things Before Breakfast and Peter Sieruta from Collecting Children’s Books) and I have been doing painstaking research over the year, determining what tales are true, which ones are false, and which ones are true but we can’t use them until certain parties quit this sweet green earth for the choir invisible.

In the course of my most recent research I decided I wanted to get at the truth behind a story that has circulated amongst the children’s literary enthusiasts for a number of years but that I’ve never seen recorded for posterity. Mainly: Did the editor of School Library Journal really threaten to hit the editor of Horn Book Magazine over the head with a chair?

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Short Answer: Yes.

Long Answer: Yes, but she had a sense of humor about it.

You see, if you’re ever able to get your grubby little paws on Robert Bator’s Signposts to Criticism of Children’s Literature (and full credit to Peter for discovering it in the first place) you can see the epistolary exchange between two editorial heavyweights, Lillian N. Gerhardt (the chair-er) and Ethel Heins (the chair-ee). Essentially what it boils down to is that Lillian wrote an editorial in SLJ about how children’s books have failed to become part of the mainstream of American literature. Heins wrote her own editorial disagreeing, and it just sort of got more and more heated from there until Gerhardt ended up finishing off one piece with, “On second thought, I may fly up to Boston and hit you over the head with a chair after all.” This, I should note, after mentioning earlier that when she was a child it was her preferred method of convincing her Kindergarten playmates that she was correct. She notes that it did often get her in trouble.

Those were the days, eh? When strong personalities could invoke World Wide Wrestling Federation techniques (nowadays it’s referred to as the Steel Chair) in the heat of their passion about books.

Let’s stop a moment, though, and see whether or not Gerhardt’s argument bears any significant merit today. Essentially she was arguing that children’s books (and she was lumping YA in there since this was 1974 and all) are influenced by adult literature but it never goes the other way around. Moreover, when children’s books do adapt to some cool adult technique (episodic novels, first-person narration, unresolved plots, etc.) it’s 20 years after adult literature has already blazed a path. “The Mainstreamers would be hard pressed to name one, let alone two, children’s books that ever turned around writing for adults.”

FYI: We won’t get into the whole is-Catcher-In-the-Rye-for-teens-or-adults debate since that’s an entirely different post right there.

When Heins responded to Gerhardt she pointed out that it was always the goal of folks like Anne Carroll Moore and Bertha Mahony Miller to tie in children’s books to the general literature at large. After all, they were making a case for tending them in the first place. But Heins concluded that the adult novel in the 20th century was relatively weak, hence authors like Isaac Bashevis Singer making their way over to the children’s side of things.

After that Gerhardt got a little nasty. I’ll avoid the oh-no-she-didn’t moments (gotta make you want to read this upcoming Candlewick book somehow, right?) but here’s the interesting part as I see it. Gerhardt says that children’s literature is clearly not a part of the mainstream since “it is still doubtful that the new sponsors of the National Book Awards will agree to restore the award in the category of children’s books.” We know today that they did indeed restore that category though I admit to being a little baffled. If Gerhardt’s letter was written in September of 1975, then the editor was raising the alarm far too early. It wasn’t until 1984 that children’s books were stricken from the National Book Awards, and not until 1996 that they were restored.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Gerhardt follows up the National Book Award scare with, “And then, please consider the implications of the actions of the newly established National Book Critics Circle. At its first general membership meeting last spring, its board of directors announced that the National Book Critics Circle would select the best essays on literary criticism each year and publish them in an anthology . . . Now, grab for one of your horns, Ethel – essays on the criticism of children’s books were specifically excluded!”

Gerhardt follows up the National Book Award scare with, “And then, please consider the implications of the actions of the newly established National Book Critics Circle. At its first general membership meeting last spring, its board of directors announced that the National Book Critics Circle would select the best essays on literary criticism each year and publish them in an anthology . . . Now, grab for one of your horns, Ethel – essays on the criticism of children’s books were specifically excluded!”

As I read this I figured it must have been another outdated statement. Surely children’s books were no longer specifically singled out as “beyond the pale”, as Gerhardt puts it, in critical literary circles. So I visited the National Book Critics Circle FAQ section and discovered the section on What books are eligible for the award? And I quote:

“We grant awards in six categories: Autobiography, Biography, Criticism, Fiction, Nonfiction, and Poetry. The nonfiction category is perhaps the most complicated: We do not give awards for titles that have been previously published in English (re-issues, paperback editions, etc.), and we generally do not consider cookbooks, self help books (including inspirational literature), reference books, picture books or children’s books. But we do consider translations, short story and essay collections, self published books, and any titles that fall under the general categories above.”

A couple rereadings later I see that children’s books are today only specifically mentioned in the context of nonfiction. After all, did not Seth Lerer’s Children’s Literature: A Reader’s History from Aesop to Harry Potter win in the Criticism category in 2009? That said, there is no specific children’s book category. It seems that insofar as you critique children’s books, you are allowed to be recognized by the National Book Critics Circle, but heaven forefend if you write a book for children specifically.

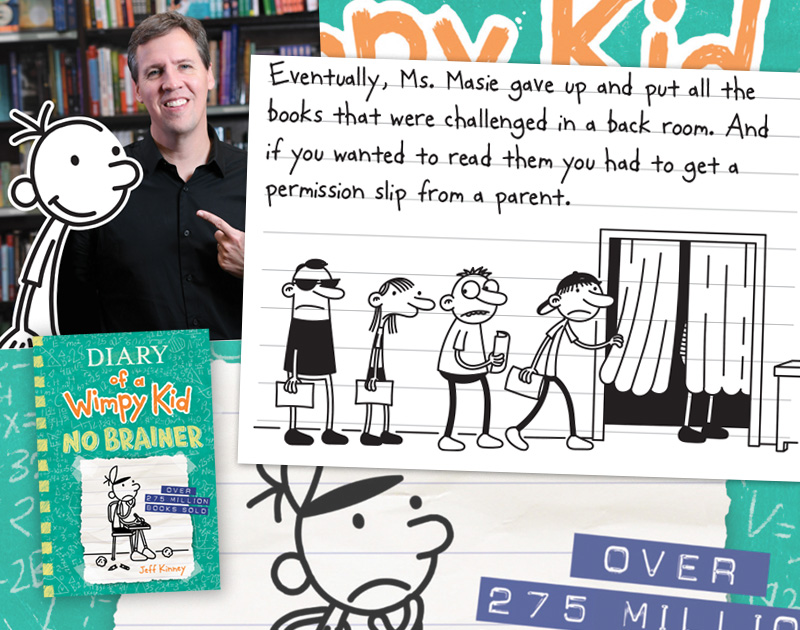

To get back to my point, though, was Lillian Gerhardt right when she said that children’s literature was not adequately appreciated by the literary mainstream? Since the time of her writing we have seen the rise of the children’s book phenomenon on a scope not seen since the days of Oz. Harry Potter, Twilight, Diary of a Wimpy Kid, ALL of these have changed the very face of literature as a whole. Or are they simply blockbuster bestsellers without any cache apart from the money they make?

Food for thought for your Thursday.

Filed under: Uncategorized

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Name That LEGO Book Cover! (#53)

K is in Trouble | Review

Fighting Public School Book Bans with the Civil Rights Act

Take Five: Middle Grade Anthologies and Short Story Collections

ADVERTISEMENT

The current huge wave of paranormal romance books in adult SFF is surely at least in part a response to the success of Twilight! But do we count subject matter, or are you speaking more about style? Are you focusing on influence or, as your last question indicates, “appreciation”?

Um, what was the question exactly? Because if you’re asking if the adult fiction crowd still considers children’s books somehow inferior in the sense of being easier to write, cutesy, or even twee, I would say the prejudice is still there. Though I suppose maybe some YA titles are being exempted from that attitude, which is why the phrase “crossover appeal” is the new marketing rallying cry for teen fiction.

As for the chair-er’s point about children’s lit being removed from the mainstream of American literature, I think most of the population is more familiar with children’s lit, at least in broad strokes, today than they were when she wrote that. The Harry Potter phenomenon helped, and so do movies of books like Holes. Plus a lot of parents seem to educate themselves a bit more about what their kids are reading or might like to read in our nice new century, where in days gone by it was often “drop them off at the library, duty done.”

But really, the most important aspect of this post is editors threatening to bash other editors with chairs. Thanks for the story; now I want your book!

Two footnotes, Betsy: Children’s books and the National Book Award have a complicated history; they’ve been ignored, allowed, disallowed, and allowed since the early 70s. LNG was talking about their disallowance in 1974. And her statement about the National Book Critic’s Circle referred to an anthology the organization was compiling, not a prize.

To the larger point: while the growth of YA for older readers (and the crossover appeal of Rowling and Pullman and the like) has lead to a *commercial* blend of adults and children’s books and reading, Lillian and Ethel were fighting about literary fiction and whether or not “serious” books for children had an impact on (or equivalence with) “serious” books for adults. I think Lillian was right then that they did not; I think she’s still essentially right even though now fewer people care about literary fiction than used to. But let’s give Ethel credit, too: she and her husband (and fellow Horn Book editor) Paul played a great part in making grownups take children’s books more seriously than they did, and Ethel was right to call out Lillian for assuming adult critics ignored children’s books for a reason more lofty than prejudice.

Good point on the anthology, Roger. I’m glad it lead to my discovery of the current rules, but it’s a huge distinction that I should have been clearer about. Reading through the letters, I go back and forth on the two points of view. They’re such odd letters to read since Lillian and Ethel often seem to be talking about two entirely different things. I also can’t help but wonder if Lillian had to restrain herself from responding to Ethel’s last editorial, since in a sense it gave Ms. Heins the last word.

If, as you say, “serious” books are discussed less in our current age, might that not give YA and children’s books the potential to influence the whole of “serious” literary fiction? And yet, as you and Lillian say, they have not. Or am I missing something larger here?

I love that Roger spoke up about this, because Horn Book Magazine takes children’s book seriously as literature.

“Mainstream”? Well, there are still places where books are reviewed that ignore children’s books. I tend to ignore such places, myself.

I know that the rise of book bloggers doesn’t necessarily say a single thing about “serious criticism,” but I do love that online there’s a solid community that takes children’s books seriously and does discuss them as literature. Since this has happened, I know that I have much less of a feeling that my interest in children’s books is a quirky interest that few adults share.

Bets, I don’t get why they would. It’s not like children’s and YA books are MORE serious than adult books. What’s interesting to me is that the era when LNG and ELH were sparring brought us some truly literary (read: difficult) books for kids that would not, I think, be published today. Books like Garner’s Stone Book or Konigsburg’s (George). Excepting some writers at the upper end of YA (M.T. Anderson, Adam Rapp come to mind), children’s literature is in a stylistically conservative time (he said, wildly generalizing).

I do see an appreciation for YA and children’s books, but largely for their economic successes rather than their quality or “seriousness”. I feel like there have been so many authors crossing over from adult to ya/children’s lately because the belief is that these books are less difficult to produce and more profitable. But I know this is an prejudice of mine, as a former bookseller who dreaded opening boxes of the latest adult author’s YA or children’s title that was guaranteed to be a smash before it even hit the floor, at least according to the book jacket.

So I do think mainstream media is aware of YA and children’s lit moreso now than ever, but whether it is being viewed as “serious” literature or whether or not juvenile literature is influencing adult literature, I can’t really say. We might need a year or so yet to see if an illustrated style like Wimpy Kid or even (fingers crossed) “Hugo Cabret” could take hold in the adult world.

A thought I had– is adult literary fiction actually all that influential or groundbreaking either? I don’t know how much it can claim that distinction anyway, let alone say that children’s lit is even less so. Anybody who wants to can claim some titles that are really influential, and put down titles on the other side for being nothing new after all, and the people on the other side can turn around and ask what the FIRST side has actually done that’s truly groundbreaking or influential lately.

I think young people’s lit has an edge with books that combine words and pictures, though, flat-out.

Also, there’s the unmeasurable influence of ALL THE BOOKS those authors of adult literary fiction read IN THEIR FORMATIVE YEARS, most of which were most likely, hmm, children’s literature….