How Much is an Author Obligated to Say?

You know, sometimes you write a review and then you spend time thinking about it long after it has posted. The advantage, or disadvantage depending on how you view it, of blog reviews is that technically you could change them at any time. But is that a good idea? If you want to clarify a point are you allowed to add onto the already existing review?

I think not. No one’s ever written a set of blog review guidelines (and even if they did, would they be followed?) regarding the pristine condition of one’s own opinion piece. Still, I think you should stand by what you’ve written and if you want to clarify a point you need to write a separate post for that very topic.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Which brings us up to speed for today! Now, two days ago I posted my review of Mockingbird, which was tough since I hadn’t written a critical review in a while. And not long after it came out, author Kate Messner and her commenters made a really good point about said review on her LiveJournal blog. At one point I complain about the fact that the author didn’t divulge her own personal connection to the material (which is to say, her daughter has Asperger’s and the book is about Asperger’s but she never mentions her daughter in any of the accompanying material). Kate rightly pointed out that what I was saying boiled down to a proclamation that an author is obligated to divulge personal details in a book if that book has a bearing on their real life.

That is not what I meant. This was poorly worded on my part, because while that is what it sounds like I’m saying, my intent was different. My point was that finding out the author’s connection to the source material was important because the material itself felt inauthentic. So when I got to the end I wanted clarification that Ms. Erskine knew about Asperger’s and wasn’t just making stuff up. When I didn’t find any evidence of the research she had conducted, I was confused about why she hadn’t mentioned her own personal connection.

Kate commented with, “Hmm…so playing devil’s advocate then… if a book feels inauthentic when you read it, but you find out the author has done research and/or has a personal connection, does that change things for you?” And herein lies the real question. Does it change things? Would my opinion of a book shift if I discovered an author either had or had not done their homework?

So I decided to test the idea out. I mean, I honestly don’t know the answer to this, but I had an idea. Let’s take five different middle grade novels and look at how I once viewed the text versus how they acknowledged their research or personal connection to the text. For my own sake, I wanted to see if I was consistent in my opinions.

My first book to consider was Singing Hands by Delia Ray. It came out in 2006 and I remember liking it quite a bit. The story was about a girl and her sister born to deaf parents. Did the author acknowledge any research done for the title? Well, in the “Thanks” section she writes, “I would like to thank Douglas Baynton for his generosity in providing insight about deaf culture and for his sensitive and expert critique of the original manuscript for this book . . . and to the Reverend Jay Croft and the members of Saint John’s Church for the Deaf for welcoming me into their lovely sanctuary . . . I am also indebted to Karyn Zweifel and the staff at the Alabama Institute for Deaf and Blind.” All well and good but it’s important to remember that this story takes place in 1948 and is historical. And since actual places and schools for the deaf are included in the text, that undoubtedly necessitated Ray’s research. So not a perfect example of what I’m looking for.

My first book to consider was Singing Hands by Delia Ray. It came out in 2006 and I remember liking it quite a bit. The story was about a girl and her sister born to deaf parents. Did the author acknowledge any research done for the title? Well, in the “Thanks” section she writes, “I would like to thank Douglas Baynton for his generosity in providing insight about deaf culture and for his sensitive and expert critique of the original manuscript for this book . . . and to the Reverend Jay Croft and the members of Saint John’s Church for the Deaf for welcoming me into their lovely sanctuary . . . I am also indebted to Karyn Zweifel and the staff at the Alabama Institute for Deaf and Blind.” All well and good but it’s important to remember that this story takes place in 1948 and is historical. And since actual places and schools for the deaf are included in the text, that undoubtedly necessitated Ray’s research. So not a perfect example of what I’m looking for.

The next book I examined was Hurt Go Happy by Ginny Rorby. Unlike Singing Hands, Rorby’s book is a little more contemporary. In the story, a partially deaf girl bonds with a chimp that knows sign language. Rorby writes in the Acknowledgments – “I began by reading books by deaf writers and by authors with deaf parents. Between working full time and graduate school, I managed sporadically to attend a few summer session sign language classes and wish to start by thanking Vicky Yancy at College of the Redwoods for her guidance in understanding the deaf community.” Yes . . . but since the book was examining not just the deaf community but also the world of chimps that can sign, Rorby had to do the research she did, right? Admittedly if she hadn’t mentioned any research at all, that would have colored my enjoyment of the text. Is that fair? In this case, I think so, but we still haven’t found a fair comparison to Mockingbird.

The next book I examined was Hurt Go Happy by Ginny Rorby. Unlike Singing Hands, Rorby’s book is a little more contemporary. In the story, a partially deaf girl bonds with a chimp that knows sign language. Rorby writes in the Acknowledgments – “I began by reading books by deaf writers and by authors with deaf parents. Between working full time and graduate school, I managed sporadically to attend a few summer session sign language classes and wish to start by thanking Vicky Yancy at College of the Redwoods for her guidance in understanding the deaf community.” Yes . . . but since the book was examining not just the deaf community but also the world of chimps that can sign, Rorby had to do the research she did, right? Admittedly if she hadn’t mentioned any research at all, that would have colored my enjoyment of the text. Is that fair? In this case, I think so, but we still haven’t found a fair comparison to Mockingbird.

Anything But Typical by Nora Raleigh Baskin hits a little closer to the mark. Like Mockingbird it took the risk of writing in the first person. Its hero, Jason, is a high functioning autistic boy and the book was considered authentic enough in its voice to garner a Schneider Family Book Award from ALA (as did Hurt Go Happy, back in the day). Did Baskin mention where she got her information? Well, the Acknowledgments (in the front of the book) read, “To Estee Klar-Wolfond, founder of the Autism Acceptance Project, who answered all my e-mails and then spoke to me (for a long time) on the phone, which turned everything around and helped me find my way into this story. To Michael Moon, current president of the Autism Acceptance Project (TAPP.com), who read a slightly-later-than-first draft of this story and gave me the greatest praise: ‘I was touched by the book for I could relate back to my childhood.’ Coming from him, it meant the world to me.” Huh. So Baskin did research the subject seriously before writing about it. Interesting.

Anything But Typical by Nora Raleigh Baskin hits a little closer to the mark. Like Mockingbird it took the risk of writing in the first person. Its hero, Jason, is a high functioning autistic boy and the book was considered authentic enough in its voice to garner a Schneider Family Book Award from ALA (as did Hurt Go Happy, back in the day). Did Baskin mention where she got her information? Well, the Acknowledgments (in the front of the book) read, “To Estee Klar-Wolfond, founder of the Autism Acceptance Project, who answered all my e-mails and then spoke to me (for a long time) on the phone, which turned everything around and helped me find my way into this story. To Michael Moon, current president of the Autism Acceptance Project (TAPP.com), who read a slightly-later-than-first draft of this story and gave me the greatest praise: ‘I was touched by the book for I could relate back to my childhood.’ Coming from him, it meant the world to me.” Huh. So Baskin did research the subject seriously before writing about it. Interesting.

Before rushing to any conclusions, let’s look at the flipside of the Acknowledgment situation. Consider now the highly acclaimed and very much beloved The London Eye Mystery by Siobhan Dowd. Think back to when this book first came out. Compared to Mark Haddon’s The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time, Dowd’s novel is a kind of locked room mystery. A boy goes up in The London Eye (that mighty English ferris wheel) and when his booth returns to the ground there is no one in it. This book got FIVE (count ’em) FIVE starred reviews. Ted, the hero, seems to have Asperger’s (though it’s never named) and like Mockingbird his story is told in the first person. The kicker? The Acknowledgments do not mention any research Dowd did. In fact, I don’t recall any objections at all to this book at the time.

Before rushing to any conclusions, let’s look at the flipside of the Acknowledgment situation. Consider now the highly acclaimed and very much beloved The London Eye Mystery by Siobhan Dowd. Think back to when this book first came out. Compared to Mark Haddon’s The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time, Dowd’s novel is a kind of locked room mystery. A boy goes up in The London Eye (that mighty English ferris wheel) and when his booth returns to the ground there is no one in it. This book got FIVE (count ’em) FIVE starred reviews. Ted, the hero, seems to have Asperger’s (though it’s never named) and like Mockingbird his story is told in the first person. The kicker? The Acknowledgments do not mention any research Dowd did. In fact, I don’t recall any objections at all to this book at the time.

What we can take away from this is the fact that clearly research is not always necessary. Or can we? Ted’s situation is never specifically named. Like Emma-Jean Lazarus he’s a different child, but not necessarily one with a label. Did I feel that Caitlin in Mockingbird had more of a label attached to her situation? And, if so, did I think that this necessitated research on the author’s part?

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

All I can really say to that is that when you compare the writing in Dowd’s book vs. Erskine’s the difference is in the reception. Folks are divided over Erskine, whereas they were universally supportive with Dowd. Why is that? Is it merely the quality of the writing, or is there something else at work?

I mention this last book The Boy Who Ate Stars by Kochka, if only because in a way it ties up everything that an author should not do. When this book came out in 2006 it was one of the first autism-related middle grade novels I’d encountered. Unfortunately, that particular novel turned the idea of an autistic boy into a kind of metaphor. A manic pixie dream child, more symbol than a flesh and blood person. When looking for how the author did the research the Acknowledgments only mention the French Ministry for Foreign Affairs. No autistic groups or personal connections. Clearly autism was simply a means to an end with this book.

I mention this last book The Boy Who Ate Stars by Kochka, if only because in a way it ties up everything that an author should not do. When this book came out in 2006 it was one of the first autism-related middle grade novels I’d encountered. Unfortunately, that particular novel turned the idea of an autistic boy into a kind of metaphor. A manic pixie dream child, more symbol than a flesh and blood person. When looking for how the author did the research the Acknowledgments only mention the French Ministry for Foreign Affairs. No autistic groups or personal connections. Clearly autism was simply a means to an end with this book.

So there we have it. And what do we have? Well, the only thing I can conclude from my findings is that when an author (or even a book’s copy) mentions that a character has a specific disability, I want some evidence that the author has a working knowledge of kids in that situation. Does an author have to divulge personal information? Not at all. Had Mockingbird said in the Author’s Note that Ms. Erskine merely had a working knowledge of the subject, that would have been enough for me. I’m not asking for credentials but rather proof that you cared about your subject.

Now, on the other hand, if a book doesn’t mention a specific disability but only hints at it, apparently that’s fine not only with me, but with the literary community at large. Why is that? Do we have to be told what to think in order to think it? Are our opinions entirely reliant on extraneous outside information? I don’t know, but what I do realize is that when writing reviews in the future I’m going to be very conscious of how my interpretation of a text is influenced by not only the words in the story, but the words about the story that accompany it. And I need to figure out if that’s a good or bad thing.

What think you?

Filed under: Uncategorized

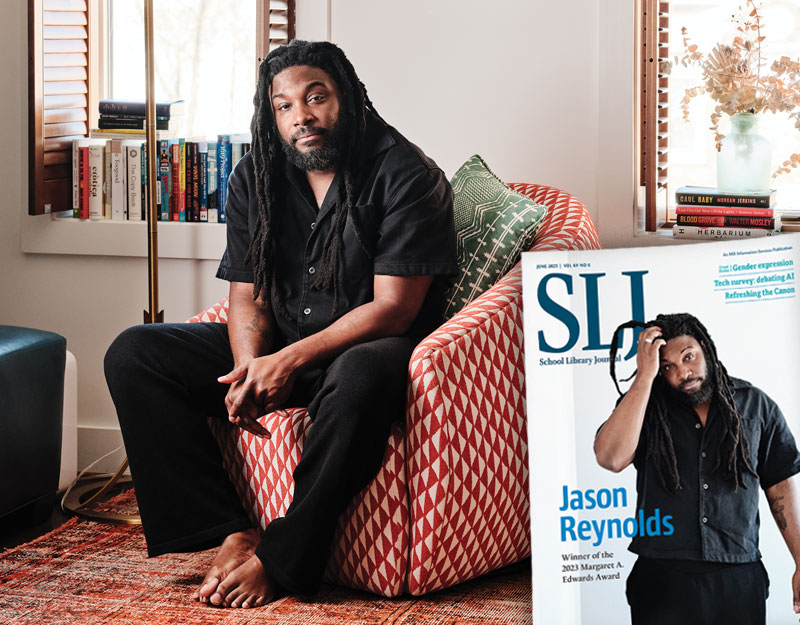

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Happy Poem in Your Pocket Day!

Family Style: Memories of an American from Vietnam | Review

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

ADVERTISEMENT

we may have one of those situations where there is a blurry line between questions of authenticity and a convincing narrative voice. had problems with MOCKINGBIRD, didn’t with LONDON EYE MYSTERY, and for me the issue with erskine’s book was that i kept getting pulled out of the narrative by the voice. first person is difficult to pull of in this particular situation because from what i can tell the author has to write more than the character might know, understand, or can clearly articulate. if the way a first person narrator thinks on the page keeps drawing my attention away from the story then that’s a problem, for me, and no authorial acknowledgment at the end is going to change that.

I suspect this has more to do with reaction to story than it does to anything else. If nothing in the writing pulled you out of the flow, you wouldn’t care about whether the author had researched out the ying-yang: the book reads well and feels right to you. When things stick in your craw, I bet that’s what sends you to the next question: hmmm, inauthentic or authentic? Unless, I bet, it’s a topic you know a ton about, in which case you would know if it was “right” or not and then simply focus on the writing/story itself.

I also think we bring our knowledge and experience to everything we do, including reading. As a result, “authenic” can actually mean many different things to different people: someone who’s lived with an Asperger’s kid has one view of what’s real, someone who isn’t personally familiar but has read about it has another, and someone with no experience at all has yet a third. But all of them might find a technique or character distracting or unlikable or, even if true, a problem in a story.

Personally, I don’t think an author owes any information about research or personal connection to story to the reader. That’s not to say that such backstory can’t impact how we read things (imagine reading James Frey before or after his news), but I really think the work stands on its own.

So, if I writer doesn’t mention their research in an author’s note, she must not have done any? Why in the world would you think that?

And demanding that people flash their disability card before you approve their book is just . . .not okay, Fuse. Someone’s disability is not a free pass to write book on the subject.

That was my entire point. I’m trying to figure out whether or not research is in any way essential to a reader’s response. And clearly it’s not if we take something like The London Eye Mystery into account. The question is whether or not a personal reaction should even be affected by research done. I’m not asking for someone to “flash their disability card”, though that was an initial reaction in the initial review. What I am trying to do is figure out if that’s even important at all. And the conclusion, you’ll note, appears to be “not really but sometimes it’s nice if the author shows they care”.

“I’m trying to figure out whether or not research is essential to a reader’s response.”

I think you’re on the wrong foot and I’m not making myself clear. There’s a difference between doing or not doing research and whether or not you put that information into an author’s note. I cannot believe that Dowd didn’t do a lorryload of research for her book. Why would you need to see an Author’s Note to believe that? Research is a necessary part of a book, but it’s not the only necessary part. You can research for years, or live with a child with a disability for a lifetime, and still write a bad book. The only thing the Author’s Note does, to my mind, is prove that you were writing in good faith. And asking people to prove their good faith upfront is just, sorry, words fail me and I’m in a rush, it’s just . . . not okay.

While research is a necessary part of a book, it’s very clear that not everyone does it.

I agree with David and Greg that feeling an author’s take on a topic is inauthentic has more to do with your own personal depth of understanding than the author’s work. While I don’t think I have owed anyone any notes in the back of Mare’s War, for instance, it seemed to really electrify discussion with librarians and teachers. I wanted people do know that this was fiction with a nodding acquaintance with facts, and wasn’t entirely my supposition. This may or may not be important to all writers.

That being said: I’m struggling to revise a novel with a main character who has spina bifida, and am intent on not making the character’s disability a plot element. I think that is what can feel inauthentic. Having not yet read Mockingbird, though, I’ll decline to comment specifically until I do some more research…

Hey Betsy,

I always thought the acknowledgements are a place to thank people, not a place to prove whether or not you did your research. I have to believe every author researches what’s important for his/her book. If a book feels inauthentic to you, you should trust yourself to find the reason in the text of the book, not the text of the acknowledgements. That’s my two cents. 🙂

I’m using Acknowledgments and Author’s Notes interchangeably, but you’re right, Brenda. The Acknowledgments are not the same thing as the Author’s Notes. Now Hope, I hear you saying that we should always assume that the author has done research and shouldn’t require them to say as such. That we should always immediately hold the authors in good faith. That’s very interesting to me and it gets to the crux of the argument. I think that this shows the essential difference between writing fiction with non-fiction elements versus writing non-fiction. Non-fiction requires that you show your work. And fiction, you say, does not. Is that right?

Oh, I just wanted to add one more thought. We talk about this sometimes in our critique group. The truth is stranger than fiction, right? But fiction has to be believable in order for it to work. So a defense of, “But that’s what really happened,” doesn’t hold water. If the story and voice aren’t believable, the author’s work isn’t done. It doesn’t matter what’s “real” or not.

Interesting post. I think that everything you need to know should be in the pages of the story. If the author does his or her job then you should feel the connection not only to the character but to any disability or whatever else the character is going through. Again authenticity should be found only in the pages of the book. It is incumbent on the author to be able to utilize and synthesize any and all research into the book. If you have to have additional source material to be convinced of the authenticity or to feel a connection to characters or story then the author has not done his or her job well. Acknowledgements are just that and shouldn’t be used to gage one’s caring or not caring of what they have written. Although I have not read “The boy who ate Stars.” if the author’s intention was to create that character as “a manic dream like child” and did it well and you felt a connection to the character and it was powerful on it’s own merits then I don’t see a problem with it. You may have felt slighted because you didn’t connect with the story and wanted some kind of additional resources to make up for it. But the fact the author didn’t list any more than one resource shouldn’t be a barometer of whether or not he cared.

Thanks for the thought-provoking post!

It occurs to me that the lengthy acknowledgements page or author’s note is a fairly new thing in fiction. I wonder if it’s fueled in part by our celebrity culture–we want to know everything about our authors. We want them to have detailed websites; we want them to blog; we want them to be John Green (aside: I wonder how much of John Green the man do we know from the vlogbrothers, even though we all feel we know him, in the way people feel they know Oprah). People seem to want a transparency that we didn’t need thirty years ago in children’s lit, except for the most beloved of authors (Laura Ingalls Wilder, for example).

Whether or not the portrayal of Caitlin rings true is obviously subjective, but anyone who is interested might look at the review by a young woman named Kimmy, who posted her thoughts on both GoodReads and Amazon. She loves the book, in spite of a few quibbles; and her feeling, as a young woman with Asperger’s Syndrome, is that the Asperger’s part of it mirrors her own childhood experiences very closely.

Hi Betsy,

Just want to say how much I appreciate your thoughtfulness in this post–It’s been really interesting following the debate about this book here and elsewhere. In your discussion re: research I’m reminded of an article (series of articles?) by Betsy Hearne called ‘Cite the Source’ that was originally published in SLJ. She argues that in order to fully respect folk and fairy tales, authors should have a clear statement about the sources they used for their book, even if they made significant changes. In order to respect the source, we need to know what it is!

I think some of that is what is going on here. I haven’t read Mockingbird yet, or most of the other titles in the post, so I can’t comment on particulars, but I think clear references to SPECIFIC research show a kind of respect for the characters/the subject, especially when a disability (that doesn’t seem like quite the right word, but it’ll do) is named. I don’t think it’s unreasonable to advocate for authors to include that kind of information in An Author’s Note, and I’m not sure what Hope’s objection to encouraging authors to “prove their good faith upfront” is, nor am I sure that requesting through author’s notes is necessarily doing that.

Anyway, this is a great discussion — thanks!

I love this thought-provoking discussion. While I think it’s interesting to know about an author’s experience with subject matter, I think it is very dangerous to say the book is more authentic when the author has direct, personal experience with it. Where then, would we draw the line? I get letters from readers all the time about my first book, LESSONS FROM A DEAD GIRL, which deals with child sexual abuse. Readers ask, “Did this happen to you?” and I think, what does that have to do with anything? Of course it’s a natural thing to wonder. But should I, as the author, have to give out personal information about myself in order to, what? Confirm it’s authenticity? Would it make them like the book more or less to know if I was abused? I sure hope not. I know this is a jump from your original example, but those jumps happen awfully fast when we move in a certain direction. Do we limit who can write books about autism to people who have children with autism? Of course not. But the review felt dangerously close to saying it would make the book more authentic if they did. I know that’s not what you meant to imply, of course.

Thanks for starting this important discussion!

Jo

I think Ms. Bird DID find several examples in the book where the voice of Caitlin sounded inauthentic to her, which she mentioned in the previous post. I also did not care for Mockingbird for several reasons and I think because it has received several favorable reviews, I was perhaps looking for a reason to validate this work as being “good”. If the author had mentioned in acknowledgements, author notes, or even just included a separate “for more information” section in which she mentioned websites about Asperger’s, dealing with grief, etc., it may have added something to the book for me. Granted, I still wouldn’t have enjoyed this book because, like Ms. Bird, I also found Caitlin’s voice to be highly annoying, but I would have appreciated knowing all the sources that the author used and may have actually looked up some of the sources to see if children with this disability actually acted like she did.

A nonfiction book without references obviously would not hold much authenticity without mentioning any sources. In like manner, I think fiction books whose plot deeply revolves around something that is nonfiction (a historical event, a disease, a school shooting, etc.), should at least mention some sources readers can consult for further information on the subject.

I tend to think a novel is independent of authors’ notes, and even intentions, and even research, i.e., there’s the novel & then there’s that other (and this may be important) stuff. First, does the novel work on its own, independent of the other? And then second, has the author presented the history, experience, etc., accurately? For example, a historical novel can work as art, but inaccurately depict the historical setting.

This is fascinating, and I’m really grateful for the post. Gives me something new to think about.

My own gut response is that it shouldn’t matters to a “reader” but that a “reviewer” approaches text differently. More critically. That’s their job.

Even so, if a book is just purely amazing, one doesn’t care, right? If the text convinces you (through voice, detail, information, etc) that the author knows the subject, you’ll assume a high level of research or personal experience. It’s when the text leaves you unconvinced that you’ll hunt for the author’s note.

That said, it is possible for a good writer to do the research, or have a personal experience with a situation/disability and still write unconvincing prose. I’d be most concerned that an author’s note about a mediocre text might talk readers into believing in the book. Because, “Well, I didn’t love the book when I first read it, but maybe I just didn’t understand.” Or something like that.

I find it interesting that we’re discussing this about disability, specifically. The topic extends to cultural/ethnic/religious/historical contexts too.

Laurel said: “I find it interesting that we’re discussing this about disability, specifically. The topic extends to cultural/ethnic/religious/historical contexts too.”

Actually, I was hoping the discussion might branch into that area as well. Look at books like Bamboo People by Mitali Perkisn or A Long Walk to Water by Linda Sue Park and the research they did. Are the books any less thrilling if you don’t know the real world background?

Really interesting discussion. I’m leaning toward agreement with those who have stated a novel’s back matter shouldn’t play into a reader’s assessment of the novel itself. Betsy, you wrote in a comment, “I think that this shows the essential difference between writing fiction with non-fiction elements versus writing non-fiction. Non-fiction requires that you show your work. And fiction, you say, does not. Is that right?” I would say that is right. Every fiction book (barring, possibly, a fantasy) has nonfiction elements, but the basic assumption is that the story is made up. Therefore, I don’t think authors should feel obligated to document their research in a fiction book’s back matter. What “non-fiction elements” would call for an author’s note, anyway? It’s fuzzy territory, deciding what kind of material is unfamiliar enough to most readers to call for it. But ultimately, I think passing off fiction as nonfiction (e.g., James Frey) is a crime, whereas a fiction book that feels inauthenthic to certain readers is just that: a fiction book that feels inauthentic to certain readers. Objective v. subjective.

That said, I would be disappointed if I read a novel purporting to take place at a certain time in history or a certain part of the world and later found out the author had “gotten things wrong.” I suppose that’s an instance where I would prefer there to be an author’s note about liberties taken with the setting or historical events.

Questions were raised for me precisely because of the Author’s Note. I felt there was a disconnect between the book and the AN. As the mom of an aspie, I read the book and felt it was written by an insider. I would have been curious but I wouldn’t have needed to know about the author’s research or experiences. But, then I read the Author’s Note, and concluded that I must have been wrong; for various reasons the author’s note did not feel written by someone with experience with Asperger’s. And then my googling began.

Betsy, Anything But Typical is written in first person, but in a neurotypical voice.

First sentence(s): “Most people like to talk in their own language.

They strongly prefer it. They so strongly prefer it that when they go to a foreign country they just talk louder, maybe slower, because they think they will be better understood.”

more from p1:

“and I will tell this story in first person.

I not he. Me not him. Mine not his.

I will try-

To tell my story in their language, in your language.”

The whole first page of ABT says a lot about ‘talking in their own language.’

Erskine is doing something very different and challenging in that Caitlin is speaking in her

own language.

As a non-fiction author, I know how important credibility is and it is part of most evaluations by editors and later in reviews.

As a school librarian, I must confess I turn to the back cover or flap, looking for something about authors unfamiliar to me and I read prefaces and acknowledgments. I don’t do this out a sense of judgment but curiosity. I like finding out more about why the author wrote this book and I do use that knowledge in book talking with my students or hand selling a book to one kid. Kids like knowing these things about author’s as well. I would imagine in this case I would tell my students that the author’s child was autistic.

Just something to consider beyond the adult reviewing process.

I’m a reader, not a reviewer, and I’m a huge fan of acknowledgments and author’s notes and such. If a book’s subject matter interests me, I do often want to learn more, and will often check out the author’s sources for more on the topic.

When a character’s words or actions seem wrong to me, and there is evidence of the author’s knowledge, I’m much more likely to consider that I held too narrow a stereotype of “what it’s like to have/be ___”. In the absence of such evidence, I’m more likely to conclude that the author got it wrong than that I did. Likewise, if an author gets some part of their story factually wrong and I know they know otherwise, I’ll assume they made a deliberate choice. If they get something wrong and I can’t tell that they know it, I’ll just assume they’re shoddy. It’s not fair, it’s not valid, it’s just how I read.

As others note, if I’m well into the story, none of this really comes up. It’s only an issue if something keeps pulling me out.

Fascinating discussion. I started a blog post in response and have revised it several times after talking to others and reading the comments here. I would have to agree that in the best of all possible worlds the text needs to stand alone. That said, I also would note that every reader brings something different to their reading of the work. Someone with firsthand experience with something in the text may respond substantially differently than someone who does not. I can think of some highly lauded books that did not work for me because I was very familiar with elements in them and so things that rang incredibly false for me didn’t for most readers. Similarly, I can think of other highly lauded books that I enjoyed, but drove friends who were close to the setting crazy with all the inaccuracies. (My blog post, by the way, is about my need for knowing more about the research done for fictionalized stories set in unfamiliar places and/or about real people. http://medinger.wordpress.com/2010/10/28/whadya-need-to-know/)

Betsy, my post is about just that featuring A Long Walk to Water!

Left out one important phrase in my post re: Anything but Typical. I am going to add in a few more sentences from P1:

“…people like to hear things in a way they are most comfortable. The way they are used to. The way they can most easily relate to, as if that makes it more real. So I will try to tell this story in that way.

And I will tell this story in first person.

I not he. Me not him. Mine not his.

In a neurotypical way.

I will try-

To tell my story in their language, in your language.”

For those who don’t like the voice in Mockingbird, this first page in ABT is food for thought.

I want to suggest, as a new topic, that not all books are written for all readers.

Isn’t it possible that the best book about a subject (I’ll use epilepsy, since I have it myself) for someone who knows the subject well might NOT be the best book to introduce the subject to someone? Simply because the “insider” voice that might make other epileptics feel understood will be hard for outsiders to relate to, without additional “introductory/explanatory” information that would make the book feel clunky to the insider?

Not sure exactly how this relates to the author’s note topic. But I find it interesting. Books written to “educate the world” about a subject might actually be less appealing to those it describes.

Then, too, not all epileptics experience seizures the same way. In fact, few do. It’s possible in some cases that the more researched a book gets (when there isn’t a personal experience at the base of the story), the more homogenized the book will get.

So interesting to mull all this.

Laurel, I don’t think there is ever a “best book on the subject” whatever the subject is. I think with most topics there is a continuum over time. First, mainstream books ignore the issue of epilepsy entirely. Then you get nonfiction about what it is, and memoirs of people with epilepsy. Then you get fiction wherein characters have epilepsy and it is a Very Special topic (Jodi Picoult territory). And finally, real integration has taken place and you get fiction in which characters have epilepsy, but the story isn’t about that (as in David Levithan’s books with GLBTQ issues). I think a lot of the frustration with white washing has come from the desire to see books about POC that are fully integrated into libraries and bookstores; neither treated as Very Special nor invisible.

To bring it all back around, from the reviews I’ve read, Mockingjay sounds like a Very Special treatment of two issues, while The London Eye felt fully integrated.

Two sidelights come to mind for me here. One of the knocks against self-publishing is that a self-pubbed book hasn’t gone through the publishing system and thus hasn’t gone through gatekeepers and gotten that level of acceptance/approval. The idea is that readers respond when they see, say, Simon and Schuster on a book – it’s a reputation thang. What I’d note is that readers here in this convo aren’t giving a book ANY credence because it’s gone through said system. Here it’s all about the author.

Also related to changes in the publishing/reading/responding landscape – much as I said earlier that the work should be allowed to stand on its own, I think it’s also clear that an author has to stand with their work. In this day and age, if you research poorly and/or misrepresent things in a book that gets any attention (or not, prolly), you gotta assume that your mistakes will come to light. This is a good thing, I think – accountability matters – and will probably probably inform author choices in a way that, perhaps, will lend credence to those choices. Or not, of course, as we do all bring our own life experience and perception into play no matter what….

I think some of this may just be a question of changing cultural expectations. What we’ve come to expect for authoritative authorial voice with real-life issues has changed dramatically over the last 35 years. Non-fiction for children and young adults wasn’t particularly transparent about its sources until Hazel Rochman’s 1986 Booklist article, which directly confronted the lack of solid documentation, and prodded people into providing the necessary information. To me, the question seems to be less “Should fiction writers be engaging in a practice which non-fiction writers have engaged in forever?” and more “Should this gradual change which occurred in children’s non-fiction, as spurred by critics, be followed by a similar trend toward increased documentation and explanation of the writer’s authority in children’s and young adult fiction?”

My gut instinct is no, because it seems a little too close to authorial intent for my liking. Generally speaking, I’m happier when I don’t know, for example, if Lois Lowry thinks Jonas died at the end of THE GIVER. I like the text to stand on its own and allow me to choose my own interpretation. I don’t think knowing what personal connection the author has to the subject matter is that far off. With nonfiction, I see how the question of authority makes sense; facts are facts, and need to be presented as such. I’m not sure the same principle applies to fiction. The CHARACTER’S authority to speak on the subject, rather than the author’s- the authenticity of the character- seems much more important.

Whether MOCKINGBIRD succeeds or fails on those merits is another question entirely, but I don’t think it does- or should- have anything to do with the author’s choices of what to disclose.

uh, death of the author anyone? okay, case closed, we can all go home!

Back from a day at the races, Betsy, and no I didn’t say that we should assume that an author does research and I never said we should assume their good faith. I am very suspicious of books written about the fad of the day. What I said was that you are wrong to assume that if an author doesn’t list her research, she must not have done any. That strikes me as silly.

I love a good Author’s Note, but to me, a good Note is one that shows me where to look for more information, not one that proves an author did her homework. When it comes to judging the book, I don’t give a rip if the author is writing in good faith. You can be a mercenary creep and write me a great book and I’m fine with that. I don’t think anyone should be persuaded that a book that didn’t work for them is somehow okay because the author has street cred.

I might be less likely to think you are a mercenary if you show me why you wanted to write a book, but I hope it won’t change my opinion of the book. I think that to *demand* you show me your good faith is insulting. And to encourage you to use your child with a diability as proof of something, is offensive. She’s a child. She shouldn’t be “used” by anybody.

This has been quite a long and interesting discussion so I’m not sure whether I have anything truly interesting to add, but…

…as a reader, I want an author’s note to answer my “did that really HAPPEN?” questions– usually when I’m reading historical fiction. I’ve read historical fiction books which have frustrated me at the end because they DIDN’T have an author’s note, and I really wanted to know where the fiction ends and the history begins.

But when it comes to contemporary fiction, I don’t care so much. In fact I’d rather NOT have an author’s note saying “As the parent of/teacher of/myself someone who is fill-in-the-blank-character-trait-of-character-here, I knew I had to write about someone who is fill-in-the-blank-character-trait-of-character-here.” THAT makes it feel topic-of-the-week, instead of just being about a character who happens to have certain traits or experiences. You can research aspects of a character’s personality/occupation/hometown/interests/whatever, but in the end the character should be a CHARACTER and not a representation of whatever-trait-you-researched. And having an author’s note SAYING a character is a representation of something just cheapens the whole experience of reading a book, meeting new (albeit imaginary) people in the pages.

I don’t want Caitlyn to be a perfect representation of someone with Aspergers. I want her to be Caitlyn. And I have to say that Caitlyn DID ring true to me, personally. She’s not, say, exactly like my brother, but why would she be? She’s her own (albeit imaginary) person!

And, I should add, finding her voice annoying shouldn’t be the same thing as finding her voice INAUTHENTIC. It actually reminds me of a WIP I have tucked away because I will never find a decent ending for it: I’d had it written in first person, and a critique partner told me the main character’s voice was annoying. (The main character was pretty much exactly myself as a 12-year-old: ouch). I ended up fixing that by going to third person, because there really wasn’t any way around it– the main character WAS annoying, but seeing her from the outside softened her. I don’t think Mockingbird would have worked in third person, though, so we’re stuck with a narrator that some people are just going to find annoying, I guess.

“And, I should add, finding her voice annoying shouldn’t be the same thing as finding her voice INAUTHENTIC.”

Great point, Rockinlibrarian.

Wow. Really intriguing discussion! What comes to my mind is that just because an author is the parent of a child with a disability that might influence voice doesn’t guarantee that the writer is capable of capturing that voice and conveying it in the context of a plot.

It seems to me, Betsy, that the book didn’t quite work for you, and you were looking for reasons. (Hmm. Were your reasons Authentic?)

On a sidenote about voice and autism, I am currently teaching a teenage boy who is either high-functioning on the autism scale or has Asberger’s (opinions differ), and his voice varies significantly: when he talks about one of the two (yep, 2) topics in life that fascinate him, he sounds like he’s 15, really quite articulate. When he talks about anything else, he sounds like he’s about 6.

And a group of children with Asberger’s will have different voices, though perhaps as a group they might have a broadly typical sound–not sure how true this is?

I have read books where the voice sounded like “author imitating his or her Platonic ideal of a kid”; that’s obviously a pitfall regardless of the main character’s personality and/or disability.

In regards to Emily’s comment: I had no intention of adding an Author’s Note to my book, The Runaway Dragon, until late in the editorial process, when I realized that if my editor didn’t recognize the fairy tales I was alluding to (tongue-in-cheek), the kids certainly wouldn’t. The AN ends up introducing young readers to the possibly unknown world of fairy tales beyond Disney, or at least I hope so.

I’m late to the discussion because I was on the road yesterday, but I just want to add that I appreciate this follow-up, Betsy, and frankly, find this whole conversation fascinating. Interestingly enough, one of the commenters on my blog today suggested that perhaps reviewers should cite THEIR sources if they’re going to take issue with the authenticity of a voice…which brings me to this. A review is ultimately, an opinion. Sometimes it’s a well-experienced, well-respected opinion that’s supported with examples – but at the end of the day, it’s still one opinion. If everyone who chimed in about liking a book or not needed to cite research to support that opinion, I suspect we’d be having many fewer conversations. And conversations like this one are good, all around.

I like what Laurel said: “…not all books are written for all readers.” But thank goodness we have so many different voices, so many choices, for so many kinds of readers.

Excellent, Kate. What a beautiful capper to all this. Not that it’s necessarily over, but you’ve summed up the value of these discussions expertly. Thank you.

I wonder if this whole issue of readers expecting fiction writers to present their qualifications to write about “subjects” is the result of a couple of decades of reading problem books. If a book becomes about a problem instead of being a story about someone whose problem is part of his/her characterization, what the author knows about her subject can begin to “show.” That’s when readers can feel as if they’ve been reading nonfiction and wonder about the author’s research. Ideally, readers should be so lost in a work of fiction that they aren’t aware of the factual material supporting the story.

I think readers didn’t raise research questions about The London Eye Mystery because it was a mystery with a protagonist who happened to have Asperger’s. The Asperger’s was merely part of his characterization, so the book didn’t read like a problem book. Whatever research the author did or whatever she may have known about Asperger’s merely supported the character, plot, and setting. As it should in a work of fiction.

Hey, and what a literary salon you had going here, Betsy.

A very interesting point–how real is real enough? I don’t look at the acknowledgments for research notes myself, and I tend to take all fact/historically-based novels with a grain of salt. If I’m really interested in a subject, I’ll do a little research on my own to see what lines up with the novel. Mostly, I’m looking for a story that highlights interesting aspects of real life (like living with Asperger’s/deaf parents/in the 1920s). If glaring inconsistencies come up, it totally takes me out of the narrative and I question everything else going forward. On the other hand, I don’t want to read a novel that feels like a research paper.

Also, there are so many different experiences for people dealing with a particular issue, it’s hard to say that there’s an “accurate” way to write about something like Asperger’s. Everyone dealing with it (a person who has Asperger’s, his/her parents, his/her friends, etc.) has a different experience. So in novels, I’m looking for that one person’s story, not perhaps the most typical story.

Wow, fascinating discussion! I feel I can’t stay silent for fear of what that might imply. Apparently, an Author’s Note that did not include the research I’d done implied that I hadn’t done any. I do need to set the record straight on that. In short, I’m a nerd. I always have been. To me, research is the only thing that makes fiction believable. I could not write a book without researching the conditions, the times, the people, the situation, the culture, the feelings, the emotions, etc.

I researched MOCKINGBIRD for five years. I researched through books and articles. I researched through workshops and seminars. I researched through interviews and observation. And, of course, I researched by living it. But simply living it is only one perspective and, in my opinion, not enough. I didn’t think an Author’s Note had to be about research. Mine was not. It was a personal note, about thoughts and feelings and motivations — perhaps (note to self!) that’s best left for interviews and blog posts outside of the book.

Thanks for everyone’s thoughts!

Kathy

Coming to this very late. I was on vacation last week and “disconnected” from all my favorite blogs.

One point I don’t think anyone made, but I apologize if it has because I’m reading through so many “catch up” posts, is that I think in these days, I would think an author would want to make at least a mention of research and or personal connection. Not so much for the reviewers, if you’re reviewing a book on the merits of the writing, it should stand on it’s own, but more for the many knowledgeable individuals or groups who would or could choose to target a book about a topic about which he/she/they consider themselves knowledgeable and therefore the book inaccurate or inauthenic.

My example would be to take us away from autism or physical challenges and take us to something like writing about a historic event or person, or a race or nationality other than the writer’s own. Nowadays, I think, thanks to all of the great listservs and blogs with discussions like this all of us are more sensitive to issues of authenticity and the portrayal of all types of people in books where readers, particularly impressionable young readers, are exposed to inaccurate or inauthentic portrayals.

I’m of the school of thought that believes fiction writers can write whatever sort of story they want about whatever type of characters live in their imaginations, but in this day and age, books are judged by more than whether it is well-written.

If I ever took to writing a piece of historical fiction or a book with characters other than my own race or ethnicity I would be sure to include some information on my research or qualifications to write about the characters just in anticipation of criticism.

Again, I don’t think authors need to provide this type of information for fiction and that the writing should be judged on its own, but they may end up being criticized for lack of it, nonetheless/