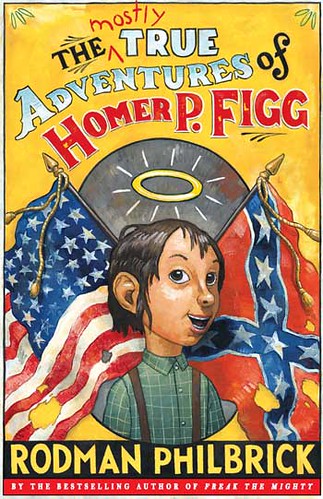

Review of the Day: The (Mostly) True Adventures of Homer P. Figg by Rodman Philbrick

Ah, the inveterate child liar. The chronic juvenile dissembler. Is there any more classic character you can name? Whether it’s The Artful Dodger, Huck Finn, Tom Sawyer, The Great Brain or Soup from the Soup books, there is always room in the canon for just one more boy fibber (girl fibbers are not yet appearing the same numbers, I’m afraid). Now the best tellers of untrue tales often come from Southern soil. They are born below the Mason-Dixon line and are capable of great feats of derring-do, all the while escaping their own much complicated shenanigans. Credit Rodman Philbrick then with coming up with a fellow that’s so far North that to go any farther he’d have to be Canadian. It’s Homer P. Figg it is. Orphan. Storyteller. And the kid that’s single-handedly going to win the Civil War, whether he intends to or not.

When you’re stuck living with a scoundrel there’s nothing for it but to make the best of things. And for years Homer P. Figg and his older brother Harold have made the best of living with their nasty ward and uncle Squinton Leach. A man so dastardly that he finds a way to sell Harold into serving as a soldier for the Union. The year is 1863 and when Harold ends up accidentally conscripted Homer is having none of it. Why his brother shouldn’t legally be serving at all! Without further ado Homer takes his propensity for stretching the truth and Bob the horse so as to catch up with the army and get his bro back. Things, however, do not go smoothly. Before he finds Harold again Homer must endure blackguards, nitwits, shysters, pigs, a traveling circus, and an unexpected tour of the stratosphere. It all comes together at a little place called Gettysburg, though, where Homer must face the facts of his situation and do his best to keep the people important to him alive. Backmatter includes “Some Additional Civil War Facts, Opinions, Slang & Definitions, To Be Argued, Debated & Cogitated Upon.”

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

I’m a sucker for a children’s book that knows how to coddle a tongue-happy phrase. Why just last year I was charmed by Sid Fleischman’s The Trouble Begins at 8: A Life of Mark Twain in the Wild Wild West with it’s delightful play on Twain’s flexible language. Now I’ve not read Philbrick before. Maybe if I picked up something like his Freak The Mighty or that The Last Book In The Universe of his I’d find a similar bit of wordplay. Whatever the matter, I found myself much taken with the syllables that get bandied about in Homer P. Figg. First there are the names. Villains get to luxuriate in monikers like Squinton Leach, Stink Mullins, and Kate and Frank Nibbly. Then there are the descriptive sentences. Leach’s villainy is pitch perfect, particularly since it is first introduced as “A man so mean he squeezed the good out of the Holy Bible and beat us with it, and swore that God Himself had inflicted me and Harold on him, like he was Job and we was Boils and Pestilence.” Another nasty character is described as one for whom “Every part of him smells of rot.” Actually, now that I look through my notes I see that a lot of the sentences I’ve highlighted as being fun descriptive passages have to do with odor. Like this later passage which reads, “The pungent perfume of the pig is still upon you. The suffocating scent of the swine exudes from your person. In a word, sir, you stink.” Catchy.

In the midst of all this wordsmithing it’s probably a temptation to let the language carry the plot and characters with little to no regard for the emotional content. But I like that Philbrick has couched this tale as an emotional quest of sorts. I mean, if you name your hero Homer then obviously there’s some kind of Iliad/Odysseus thing going on there. Particularly if you push said hero into a quixotic series of scrapes. I kept sort of expecting our own Homer to go blind at one point, but if Mr. Philbrick ever felt the urge to remove his Homer’s sight he did a noble job of repressing that inclination. Instead he builds on Homer and Harold’s relationship. One example comes when Homer thinks about a time when he climbed onto a barn roof when he was younger. “It was a mean thing, wanting to scare my big brother who had always been so kind to me. But if felt good, too, like I enjoyed testing how much he loved me.” So a book that could simply have been a series of unrelated incidents is held together by good old-fashioned brotherly love.

I mentioned at the beginning of this review what a novelty it is to find a casual liar like Homer coming out of the North rather than the South. And when Homer mentions on the very first page that he and his brother won the Battle of Gettysburg, then that he was from Maine on the second, I should have realized the connection. After all, I saw Gettysburg the film when it was in theaters. But it takes an author like Philbrick to put the pieces together for a reader like myself. Pieces he has a clear view of and isn’t about to mess up. He doesn’t romanticize war any either. At one point Homer makes a mad ride across a field of battle and what follows is an emotionless list of the horrors he witnesses along the way. Things like “Thirsty men sucking sweat from their woolen sleeves” and “A dead man on his knees with his hands folded, as if to pray.” Mamas don’t let your children grow up to be Civil War soldiers.

I was also interested to see that Homer mentions historical details that kids don’t always get a chance to see in school. Facts like, “when President Lincoln declared that slaves in the Confederacy were free, he didn’t dare free the slaves in he Union states like Maryland, Delaware, or Kentucky, in fear the border states might join the rebels.” Children’s literature has a tendency to sort of bypass that kind of information, but I think it makes a historical novel like this one all the richer for its complexity. And of course all historical novels for children grapple with a question that is never easy; How do you deal with terms that are historically accurate and odious to contemporary ears? I refer, of course, to “the n-word”. Now, to be perfectly honest, there are at least two villains in this book that should be tossing that word back and forth like it’s nobody’s business. Yet they don’t. They don’t and I admit that this didn’t ring untrue to me while reading the book. It was only later that I stopped myself and went back to see how Philbrick dealt with that conundrum. The answer is that the bad guys say either “slave” or “darky”. And there might be some problems with the “d-word” as well, were it not for a good Quaker man who corrects Homer on this point later on. “If a man has dark skin, say that he is colored, or that he is African.” I’m sure that some historians amongst us might have something to say about those terms as well, but as far as I can tell Philbrick covers his bases and doesn’t have to cheat. Later Homer also refers to two workers as “Indians” though he acknowledges, “These Indians are from China – similar eyes, but a different tribe.” Contextualizing ignorance in terms that modern kids can understand. A tough job.

No matter how tough the subject matter or the work, Homer P. Figg is a strong and snappy little novel. Funny and with a plot that keeps moving at a lightning quick pace. Very few readers will find themselves bored by what Philbrick produces here, and many will be caught learning a little something in the process. One of the best of its kind.

On shelves now.

First Line: “My name is Homer P. Figg, and these are my true adventures.”

Notes on the Cover: You know, I wasn’t sure what to think about this one at first. David Shannon on a middle grade? But the longer I look at it the better it gets. I mean, what does David Shannon mean to you? To a lot of kids, he brings to mind humor and hijinks. And with his David books now in their eleventh year, a lot of kids who have grown up with Shannon trust him to keep them amused. They’re going to gravitate to this book, and that’s a boon. So after some consideration, I am definitely a fan. Plus it has the additional added benefit of not looking like any other book out there. Bonus.

Other Blog Reviews:

- Eva’s Book Addiction

- Reading With My Ears [an audiobook critique]

- Sweet Reads [comes with recipe]

- Not Just for Kids

- The PlanetEsme Plan

- Cloudy With a Chance of Meatballs

- Sarah Miller

- The Goddess of YA Literature

Misc: An interesting piece in which Mr. Philbrick discusses the fact checking done on this book.

Filed under: Reviews

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

One Star Review, Guess Who? (#202)

Exclusive: Giant Magical Otters Invade New Hex Vet Graphic Novel | News

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

Take Five: LGBTQIA+ Middle Grade Novels

ADVERTISEMENT

I am interested in your take on David Shannon. Since he did three serious books of mine early in his career (THE BALLAD OF THE PIRATE QUEENS, ENCOUNTER, SACRED PLACES) it’s difficult for me to think of him as an illustrator of ”

Not sure what happened there–here is the entire post:

I am interested in your take on David Shannon. Since he did three serious books of mine early in his career (THE BALLAD OF THE PIRATE QUEENS, ENCOUNTER, SACRED PLACES) it’s difficult for me to think of him as an illustrator of “Humor and hijinks.” Of course you did weasel a bit and say “a lot of kids” feel that way.

But not this kid. I like his humor, I adore his serious side.

Weasel? Unnecessarily harsh words. After all, this cover is not indicative of his serious side. The style is much in keeping with David and other books along those lines. It looks like he’s deliberately invoking his sillier stuff. So that’s how probably how kids are going to interpret this cover. No weaseling here.

It is always really hard to get children interested in historical fiction. If they like history, they mostly gravitate to nonfiction. I loved all the historical references and the learning experiences this book provide. But topics like war are hard to sell if there are some other plot lines like brotherly love and some good ole’ humor.

After reading that line about Boils and Pestilence, I couldn’t stop thinking about that phrase for a week… 🙂 Loved it.

M. Germano

Read, Read, Read!

Too bad you can’t go back and edit comments…

“…war are A hard sell if there AREN’T some other plot lines…”

My Bad

Thank you, Elizabeth. No author could ask for a more thoughtful, or thought-provoking, review. As to the David Shannon cover, I can only think myself fortunate to have one of the best writer/illustrators creating a cover that really ‘says’ something about the contents. I’m especially fortunate because David created the cover for my first book for young readers – ‘Freak The Mighty’, as well as ‘Max The Mighty’, ‘The Last Book In The Universe’, and ‘The Young Man And The Sea’. And no, I’ve never met him but hope to one of these days!

Oh, what a lovely surprise. I’m glad you liked my review. And strangely enough I myself have met Mr. Shannon. He is the sweetest fellow this side of the Mississippi. A truly charming individual. I hope you get a chance to speak with him someday. Now I’m off to reexamine that ‘The Last Book in the Universe’ jacket.

I enjoy David Shannon’s artwork and don’t mean to offend; but honestly, I think that the cover art might scare away readers who would otherwise enjoy the book, but are too concerned with looking “cool.” Alas, there are such kids. I think the book, BTW, is an absolute winner.