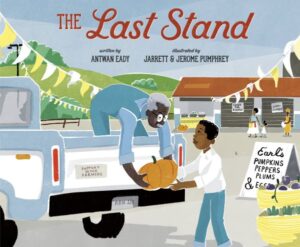

The Last Stand: A Talk with Antwan Eady and the Newly Caldecotted Pumphreys About the Book

I have a treat for you today.

If you’ve already seen a copy of the new picture book THE LAST STAND by Antwan Eady with art from Jerome and Jarrett Pumphrey then you know how good it is. This is a book that’s already been raking in the starred reviews. SEVEN of ’em, to be precise. We’re talking Publishers Weekly, Kirkus, Booklist, BookPage, etc. Not too shabby, right? I didn’t know any of that when I picked the book up to read for myself, and what I found on the page I found particularly intriguing. Here’s the publisher’s description:

“Every stand has a story.

This one is mine.Saturday is for harvesting. And one little boy is excited to work alongside his Papa as they collect eggs, plums, peppers and pumpkins to sell at their stand in the farmer’s market. Of course, it’s more than a farmer’s market. Papa knows each customer’s order, from Ms. Rosa’s pumpkins to Mr. Johnny’s peppers. And when Papa can’t make it to the stand, his community gathers around him, with dishes made of his own produce.”

Today, it is my utter delight and honor to speak to both author Antwan Eady and Jerome and Jarrett Pumphrey about the book, where it came from, and a whole host of other things that you will DEFINITELY want to know after you read the book for yourself.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Betsy Bird: Antwan, thank you so much for taking the time to answer some of my questions today. While this is certainly not your first picture book, it does feel like it may be your most personal so far. Could you tell us a little about how the idea behind THE LAST STAND first germinated? What sparked an interest in writing this book?

Antwan Eady: Thank you for having me. I knew one day I’d tell a story about the community I grew up with as well as communities I’ve come to know. I just didn’t know when I’d tell that story. However, in 2020 we witnessed food shortages, supply chain issues and more. And for so many of us, we found solace on Saturday morning trips to the farmers’ markets. There was fresh air, fresh produce, fresh everything. More importantly, we were also able to support farmers who’d gone above and beyond for us during such unprecedented times. That’s when I knew the time to go from idea to story was now more than ever. The Last Stand is a thank you to those farmers.

BB: I think it does precisely that. And Jarrett! Jerome! Thank you so much for answering my questions too! And congrats as well on your (much deserved) Caldecott Honor! So how did you come to the manuscript of THE LAST STAND? And what drew you to this project?

Jarrett Pumphrey: Thank you, Betsy! For having us and for the kind words. Well, I’ll be honest, I had to dig through my email to refresh my memory as to what exactly happened. What my excavation uncovered is that our agent Hannah Mann had forwarded us the manuscript along with a lovely note from Rotem Moscovich, editorial director of picture books at Knopf. Rotem gushed over Antwan’s text (rightly so) and thought we’d be a perfect fit for the art. She hoped we’d see what she saw—a beautifully rich, multilayered, intergenerational story that spoke to audiences both broad and specific. She also wanted us to hear Antwan share his own personal story about growing up in South Carolina, his Gullah Geechee culture, and the history of Black farming in America, so she included a video of him doing just that. Well, Rotem knew exactly what she was doing because, man, did we fall hard for this project. Antwan’s manuscript was everything Rotem said it was and after a brief call with Hannah to confirm that even though this would be the second intergenerational story set on a farm we’d be illustrating (see THE OLD TRUCK), there was absolutely no way we were passing on this project. We really wanted to help Antwan tell this story.

BB: I hadn’t thought about it, but you’re right. This is your second intergenerational farm tale. Huh! Along those lines, Antwan, you also take time to mention that “land is complex” citing sharecropping and lands taken from Indigenous and Gullah Geechee communities. What’s your own personal connection to the community featured in this book?

AE: I was born in Beaufort, South Carolina and raised outside of it in a self-sustaining community like the one we see in The Last Stand. Instead of a farmers’ market, our farmers sold produce and more out of their pickup trucks at convenience stores, on the side of roads, and, at times, they’d drive by our homes to see if we needed anything. Beaufort, SC, is also known as the Lowcountry. It’s a part of a corridor where African Americans, with predominantly West African retention, exist. And we’re known as Gullah or Gullah Geechee. The retentions I mentioned earlier are often seen in our customs and traditions, arts, and crafts, and in our food and language. There’s also a moment in the story where Mrs. Rosa teases Papa for moving like a cootah. Cootah is the Gullah word for turtle. And it’s one of the few words I remember my grandma saying repeatedly when we went fishing. There were always plenty of cootahs around.

BB: Thank you. Jerome and Jarrett, tell us a little bit about your process when you have a manuscript and you have to figure out how to present it. Do you two sketch out your ideas together or come up with them separately?

Jerome: This was only our second time illustrating a book together that we didn’t also co-author, so our process is probably still evolving, but what we’ve done so far is we read the manuscript separately to get a personal sense of the visual story (making notes and maybe a few thumbnails). Then we worked our way through the manuscript together, sharing our notes and thoughts, figuring out the visual story spread by spread.

Jarrett: At the time, Jerome was living in Florida. I was in Texas. So, it was a lot of Facetime and phone calls just talking through different ideas and taking notes. Lots of “Ooh, what about this…” inevitably followed by “Um, no, but what about this…” Back and forth. Anything goes. Good and bad ideas. We put it all out there. Eventually, we landed on something that was a blend of both our ideas, compositions that featured both our perspectives. Then Jerome took our notes and did the initial sketches for the dummy.

BB: Antwan, in your Author’s Note you write, “I’ve taken heartbreak and turned it into a story about a boy and his grandfather who now have the last stand at a farmer’s market in a community that can’t afford to lose it. I’ve taken the pain from our world to create beauty in another.” Picture books that do what you have done here stand as correctives and guides for our young readers. What then, to your mind, is the role of a picture book like THE LAST STAND beyond righting a wrong in the real world? What can this picture book do to help?

AE: The Last Stand brings farmers to the center stage. Thus, allowing young dreamers to know that it’s aspirational to become one. The Last Stand also brings Black farmers into a narrative that has overlooked them time and time again.

But, beyond righting a wrong in our world, The Last Stand leaves readers with hope. We see it on the last page where the Pumphrey Brothers are visually telling us that hope and change are on the horizon for this community. Sometimes it’s difficult for us to become (or believe in) what we’ve yet to see is possible, but now, we’ve created a place where hope and change exist. It’s a call-to-action to carry that feeling with us when we finish this story and take that feeling from Papa’s world to ours.

BB: I noticed that the text of THE LAST STAND comes in three acts. In the first act you have the boy and his grandfather gathering and selling. In the second the boy is on his own and he’s uncertain. And in the third it’s just the boy but he’s confident. You repeat specific images, like of gathering the eggs, between the first and third acts. When you’re first figuring out the art, is it clear how to illustrate such scenes from the get-go or do you come around to such decisions later in the process?

Jerome: Wonderful observation! There were some things that stood out from the get-go just on reading the manuscript, such as the rhythm of Earl’s and the grandson’s Saturday routine. There was this clear echo occurring between the acts. That did stand out to us, and we could immediately envision supporting that with similarly rhythmic imagery. It took a bit of experimenting to figure out what the compositions would be and how to have similar images that don’t feel too repetitive or dull.

Jarrett: We love a good visual echo. It’s such a great way to show how things both change and stay the same. We can’t always do it. In LANGSTON, for instance, I don’t think we did it at all—there was plenty else going on in that book anyway. But in this case, it made a lot of sense and occurred to us pretty early on. I think my favorites are the chicken coop scenes. We could have shown those scenes a number of different ways, and even made each instance entirely unique, but it just hit harder seeing it framed the same from inside the coop each time. The trickiest part, as Jerome mentioned, is just figuring out how to do it without it getting too repetitive. One day we’ll figure out doing a whole book where the camera never moves—like, we see an entire story unfold from inside the dog’s house or something—but here, the clear three-act structure made three the perfect number for looking-out-of-the-chicken-coop shots.

BB: Speaking of the gentle repetitions in the book, Antwan you go through the process of collecting the food and then taking it to market/delivery three times, which is reflected in the art. Once I noticed it, I saw that the book is essentially cut into three acts. Was that how you originally wrote out the story, or did you come to that format through the editing later?

AE: Thank you for noticing. Telling The Last Stand in three acts felt right/necessary. I knew I needed to show what a normal Saturday was like for Papa and Little Earl. I knew I wanted to leave readers with hope in the end. But it was in the middle where I wanted readers to understand who Little Earl is and what this community means to him, too. That was Little Earl’s hero’s journey. Of course, there was much story to flesh out thereafter. But the format was there originally.

BB: Jerome and Jarrett, when you were first coming up with ideas for how to illustrate this book, were there any ideas that you came up with that you eventually rejected?

Jerome: There were no scrap-everything moments on this project, which almost feels like a first for us. From first draft to final draft, the main changes were in tweaking compositions to ensure the best experience in taking in the visual story.

Jarrett: Yeah, this one was refreshingly smooth. I think it speaks volumes to how well Antwan crafted his text and how well we connected with it.

BB: That’s awesome. Antwan, did you know the Pumphreys before they came to work on this book? How do you feel about the final art?

AE: A dream collaboration! I knew them through their previous works like The Old Truck and The Old Boat. I’ve had conversations with them online, too, but I’d never met them outside of those spaces. But I was a fan, and they were a dream collaboration for me…one that I didn’t think was possible this early into my career. But what I didn’t think was possible, our editor, Rotem Moscovich, made possible. I can’t thank Jarrett and Jerome enough for sharing space with me here.

With regards to the final art, I feel like so many others. The Pumphrey Brothers are talented, so I consider myself lucky to have them lend that talent to my story. I stare at our book often and I feel joy on every page. It’s vibrant and beautiful. The community that exists here is the type of community I wanted to share with readers, and the Pumphreys delivered that (and more) for sure.

BB: Finally, what’s everyone working on next?

AE: I’m drafting/editing two picture books this year as well as a middle grade novel. So, I’m excited about completing those projects.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Also, The Gathering Table (illustrated by London Ladd) will be released next year. A companion story to The Last Stand, The Gathering Table is inspired by a special table in my life. It follows a family year-round as they celebrate special occasions around a table in their backyard where food and relationships connect, and Gullah Geechee culture and traditions are shared. I’m thrilled to be working with London, and I’m currently reviewing sketches.

Jerome: I’m working on illustrations for a beautiful story called SO MANY YEARS by Anne Wynter. It looks at the subject of Juneteenth in a way I haven’t seen before. I’m right in the middle of final art for this one. I’m doing the art in acrylic paint on wood panel.

Jarrett: And in the meantime, I’m finishing the text for the next book in our LINK & HUD hybrid graphic novel/chapter book series, LINK & HUD: SHARKS & MINNOWS. The brothers are back, and this time, their imaginations are wetter than ever.

I can’t thank Antwan, Jerome, and Jarrett enough for taking the time to answer my questions today. Thanks too to Kathy Dunn and the folks at Penguin Random House for putting this all together. The Last Stand is on bookstore and library shelves everywhere so go and take a look at it for yourself.

Filed under: Best Books, Best Books of 2024, Interviews

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Name That LEGO Book Cover! (#53)

Exclusive: Vol. 2 of The Weirn Books Is Coming in October | News

Fighting Public School Book Bans with the Civil Rights Act

North Texas Teen Book Festival 2024 Recap

ADVERTISEMENT