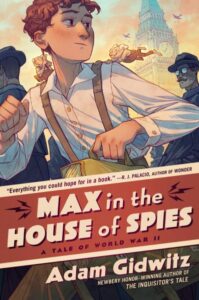

Review of the Day: Max in the House of Spies by Adam Gidwitz

A lot of children’s librarians started out as English majors. I’m not surprising anyone with this information, of course. And I’m no different than anyone else. When I was in college I dutifully went through my paces, learning such extraordinary new English terms as phallocentric patriarchy, post-colonial literature, magical realism, and more. That last one, magical realism, was the one that tended to flummox me. What precisely did it mean? I understood the definition you can now find on Wikipedia these days (portraying, “fantastical events in an otherwise realistic tone”) but where did the line fall between what was fantasy and what was magical realism? As I grew up and became a children’s librarian, this question followed me. I discovered that while most books for kids fall squarely into that “Fantasy” genre, there is the odd, occasional exception. Max in the House of Spies is an almost perfect example. Here we have WWII spy antics, hungry kangaroos, and a hero determined against all odds to help his parents, even if that means fooling Nazis. It also has two immortal creatures clinging to our hero’s shoulders, like a Greek chorus consisting entirely of a pint-sized Statler and Waldorf. I doubt anyone would disagree with me that this book is a fine example of magical realism. The real question then becomes, did it have to be?

Max is not happy. He’s an unwilling Kindertransport refugee, having been sent from Germany by his loving parents to London to stay with whatever family will take him in. Max is Jewish and separated now from his mother and father he’s incredibly worried. Those two are the people Max had sworn to protect (even though he’s just a kid himself). Vowing to find some way to return, Max is soon to discover that the family that has taken him in has distinct connections to Britain’s intelligence agencies. Now Max has a new goal: Become a spy for the British so that he can be sent back to Germany as soon as possible. Oh. And one more thing. He has two immortal creatures, a dybbuk named Stein and a kobold named Berg, permanently stuck to his shoulders for, potentially, the rest of his life. What could go wrong?

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Now Adam Gidwitz isn’t being easy on himself when writing this book. He could easily have gone a sloppier route and written something relatively formless in the vein of the Spy School series n’ such. Instead, he’s willing to grapple with enough complexity to feel authentic, but not so much he loses his child readers along the way. Take, for example, the degree to which the adults are on board with Max’s plan to become an Allied spy against Germany. Each responsible adult in the book is vehemently opposed to this plan. Not only is this more believable, but it also makes each one of those adults more inherently sympathetic. No mean task! Then there are the other complications. Gidwitz gets amazingly complicated in the character of Uncle Ivor, a defiant communist at a time when Stalin was not in favor in England. I liked very much the different aspects of his character. Finally, Adam takes time to acknowledge that while fighting Nazis (a downright heroic thing to do) the English also had their own fair number of anti-Semites and history of colonialism to contend with. Two characters in the book, Max’s schoolmate Harold, whose family hails from India, and Sergeant Toby Thompson from Trinidad (with ample time taken to explain the Trinidadian Revolution) don’t get much page time, but when they do appear they are three-dimensional characters quick to puncture any glorified idealism you might have about England itself. It’s a bold choice for any writer, but Gidwitz makes it work.

I like spies, sure, but my favorite genre for kids can pretty much be summed up as “clever kids being clever”. Max certainly falls into that category, since time and again Gidwitz makes sure that the reader can see Max outsmarting bullies of various shapes and sizes. Honestly, I’ve been trying to think of Max’s literary predecessors in this respect. Which is to say, seemingly powerless kids that through wit, cunning, and/or sheer audacious intelligence keep wicked adults on the ropes. Peter Pan, alas, fits the bill and so do Maniac Magee and Styx Malone. It’s interesting, but normally this kind of character is met secondhand. The narrator will be a veritable Nick Carraway to their Gatsbys. Gidwitz, in contrast, makes Max our hero and doesn’t separate from him. How does he make that work? Enter the dybbuk and the kobol.

So my current working theory about Stein and Berg is that they serve as one of the few methods Gidwitz has at his disposal to enter the mind of his hero. Since Max travels on his own to England, he has no friend or close companion to confide in. The closest thing he has are these two spirits. But really, more than anything else they’re stand-ins for the child readers. When Max does something we don’t understand, the spirits kvetch to an amazing degree. They spell out what we, the readers, are thinking ourselves. But this begs the obvious question: Are they necessary?

I wrestled with this very question for a while with this book. As far as I was concerned, Gidwitz has conjured up a cracking good spy thriller. Granted it’s clearly the first in a series (it ends just as he enters Germany again) but the spy lessons that Max has to participate in are sublime. I’ll be honest and tell you that though maybe Berg and Stein fulfill some greater purpose in future titles involving Max, here they could come right out. Oh sure, there is admittedly a moment near the end where one of the spirits proves its usefulness to Max on his current trajectory. This moment is foreshadowed earlier in the book when Max is asking the spirits to tell him a piece of information he couldn’t possibly know, so that he can verify it and know that he isn’t going mad. But beyond that, the only other reason I could imagine Gidwitz included them was to say something about a spirit of Germany that preceded the Germans, and had a magic of its own. Who’s to say? All I can note is that if they bug you, don’t worry. Stick with the book. Like Max, you’ll find them easy enough to ignore over time.

Without a doubt, Max’s training sequences in this book are the best of the best. Bar none, my favorite parts to read. And if you glimpse the backmatter included in this book, you’ll see the author did his homework in this regard. It ends far too soon, but that just means kids will be clambering for more when a sequel is produced. And who knows? Maybe they’ll like the kobold and dybbuk more than I did. Gidwitz appears to be having fun with this book, and a writer who knows how to have fun is a writer who knows how to get kids to have fun reading their books. Fun, fact-filled, exciting, and unafraid to ask the tough questions, dip deep into this one when you can. Then get ready to want to read the next one immediately.

On shelves February 27th

Source: Galley sent from publisher for review.

Filed under: Best Books, Best Books of 2024, Review 2024, Reviews

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Tegan and Sara: Crush | Review

The Seven Bills That Will Safeguard the Future of School Librarianship

Take Five: Dogs in Middle Grade Novels

Gayle Forman Visits The Yarn!

ADVERTISEMENT