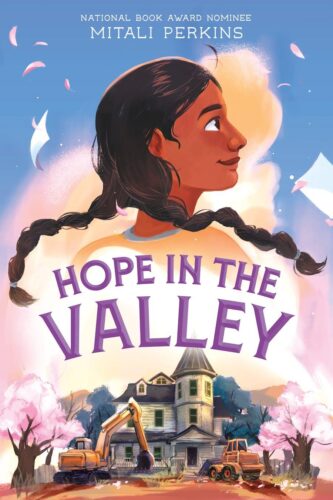

Hope In the Valley Twofer: An Interview with Mitali Perkins AND an Exclusive Excerpt!

I’m getting greedy in my old age, folks. Time was when I’d be content to do an interview here and an exclusive excerpt reveal of a novel for kids there. Now? I want it all, baby! Both an interview AND an excerpt! This bad behavior may never be corrected either, because today I’m getting precisely what I want. Not only are we going to talk to the one, the only, the great Mitali Perkins about her July 11th release of her latest book Hope In the Valley but we’re going to read some of Chapter 5 as well.

Here’s a little description of what Kirkus called, “A riveting, courage-filled story,” for you to kick things off:

“Twelve-year-old Indian-American Pandita Paul doesn’t like change. She’s not ready to start middle school and leave the comforts of childhood behind. Most of all, Pandita doesn’t want to feel like she’s leaving her mother, who died a few years ago, behind. After a falling out with her best friend, Pandita is planning to spend most of her summer break reading and writing in her favorite secret space: the abandoned but majestic mansion across the street.

But then the unthinkable happens. The town announces that the old home will be bulldozed in favor of new—maybe affordable—housing. With her family on opposing sides of the issue, Pandita must find her voice—and the strength to move on—in order to give her community hope.”

Mitali was kind enough to answer some questions for me about the book:

Betsy Bird: Mitali! Thank you so much for taking the time to talk with me today! Just to kick us off, could you tell us a bit about where the idea for HOPE IN THE VALLEY came from?

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Mitali Perkins: My fiction is often rooted in both the personal and the political. I wanted to write a novel about a shy, old-fashioned girl who doesn’t want to grow up and resists change, because that, in a nutshell, was me in seventh grade. Also, since affordable housing is such a controversial and crucial issue here in California, I sought to delve into the historical roots of the zoning and planning issues that got us into such a quagmire. I went to college in Silicon Valley during the time when orchards (the place used to be called the Valley of Heart’s Delight thanks to their magnificent blooms) were torn down and replaced with commercial office buildings, housing developments, and mini-malls, so I set the book in that era. I studied political science as an undergrad, got a master’s in public policy, and am still hooked by the weirdness and wonder of local government in the United States.

BB: Oo. I love that term: “weirdness and wonder”. I confess that this may be the first middle grade novel I’ve seen that talks in any way about affordable housing and the debates on either side. I’m always particularly interested in how complicated and complex issues are discussed in books for kids. What were the points that were the most important to you for this book to hit?

MP: I never like vilifying characters (let’s call them tropes) to hammer home my personal beliefs because I believe children are capable of navigating nuance. They might be even better at it than we are because they are less rigid and still in formation. In most of my books, I try to give my young readers dignity and space to think for themselves when it comes to justice and goodness. What compassion might we offer an unemployed, dedicated father who seeks to put rice on the table for his family by poaching tigers illegally (TIGER BOY)? Is a Burmese soldier the bad guy if he’s abducted and forced to fight in a ruthless army (BAMBOO PEOPLE)? How do rule of law and the grace of a particular family’s narrative clash along the border wall (BETWEEN US AND ABUELA)? What happens when the privacy rights of a first mother conflict with an adoptee’s desire to know about his family of origin (FORWARD ME BACK TO YOU)? And so on.

In HOPE IN THE VALLEY, I created characters who express a range of opinions around a property for sale in their town — should they preserve it for history’s sake, let the market determine what happens, or employ it to maintain diversity and equity now and in the future? In the fictional town of Sunny Creek, as in small towns and cities across the United States, many people care deeply about the flourishing of their community. We disagree, however, about the means to get there. Essentially, my novel explores this broad question: How might we honor good from history while not letting the past impede a more just future?

BB: You’ve been writing novels for kids and teens since 1994, I do believe. In that time you’ve seen just huge changes hit the publishing market. How have these changes in publishing affected your writing over the years? Are there aspects of HOPE IN THE VALLEY that you don’t think could have been published in the past, or does it not feel too different to you today?

MP: I have an amazing video of you and several other librarians dancing Bhangra at one of my book launches a hundred years ago. You were good, actually, but I could definitely use the footage as blackmail for several other participants. Awkward dancing might be the perfect metaphor for my career because the market and I have been out of rhythm since the start. An odd intersection of identities might be the problem. At first, some doors were closed because I was delving into my Bengali-American heritage and writing books featuring brown protagonists in other parts of the world without including any western bridge characters. So, so many rejections came my way. Over the last couple of years, I’ve written a few faith-forward books, but the market doesn’t seem to like that Jesus is my guru. Oh, well. I’m getting better at my craft and some of my books still Bhangra their way to readers. It’s a marvelous vocation.

BB: Darn tootin’ I was good. And yeah, I think you’re right about getting Jesus in the book. Shannon Hale can get a little in there, but I feel like she’s the only one in the commercial market. So was there anything in this book that you wanted to include, but just couldn’t for one reason or another?

MP: Not really. I always write spare and have to flesh out my plot. What makes me happy is that in HOPE IN THE VALLEY, my main character Pandita pens the poems I wrote when I was twelve. Could the seventh-grade version of Mitali, scribbling verse in her notebook after yet another hard day at school, have predicted that her poems would one day be published in a novel? No way. And yet, here we are.

BB: Indeed! Finally, what’s next for you! What can we hope to see in the future?

MP: I’m under contract for another MG novel with Macmillan and my editor Grace Kendall and I are in conversation about that one. I’m so grateful for her and my wonderful agent, Laura Rennert—she’s represented me for my entire career, which I know is unusual. This fall, I have a Christmas picture book coming out from Penguin Random House called HOLY NIGHT AND LITTLE STAR, illustrated (illuminated might be a better word) by *the* master of color, Khoa Le. And then next year, another picture book, BETWEEN MY HANDS, releases from Macmillan. It’s a collaboration with the talented Naveen Selvanathan, who is the art director at Netflix. You want more? Here you go: I’m currently writing a mystery for Charlesbridge set in a Bengali village before Partition called THE GOLDEN NECKLACE, and am also under contract for a nonfiction book with Broadleaf Books that explores the intersection of justice and art. JUST CREATIVITY was inspired by a question I had the privilege of asking the late poet Mary Oliver, “How might a poet serve the poor?” In short, I’m a busy, satisfied writer, Betsy. Thanks so much for hosting me and supporting my career over the years.

And thank YOU, Mitali, for answering my questions so generously.

Now, folks, I am pleased to reveal to you, an excerpt from Hope In the Valley:

CHAPTER 5

A roar of machinery outside my window jolts me awake. I leap to my feet. It’s morning. I’m still wearing my overalls and T- shirt from yesterday.

And then I remember: the demolition! I dash to the front door and hurl it open. Screeching to a halt on the porch, I gasp. What time did they start? How could they have done so much? Bulldozers and tractors are tearing down the old barbed wire enclosure, and our secret entrance is gone, along with the oleander bushes and the rosemary. Even the weeds are being ripped up in the claws of the bulldozers.

I try to see behind the machines to the house and the orchard. Looks like the fruit trees are still there. With the bushes and weeds gone, I can see the roof of the old

Johnson house. It’s still there, too.

For now, at least.

I have to get to our swing!

I race down the stairs and across the street. Baba shouts my name, but I don’t stop.

One part of my brain registers the sharp asphalt under my bare feet. Before they hit dirt, a burly dude in a construction hat blocks my way.

“Stop, kid!” he yells. “You can’t go in there! Where’s your mother?”

Before I can answer, Baba’s beside me. “I’m her father. Sorry, sir.” He pulls me away from the man.

“Baba! I have to get in there!” I shout to be heard over the machines.

“Why?”

I move closer and he leans toward me: “I . . . I used to sneak through the fence sometimes.” My confession is about one centimeter from his ear.

Baba’s head jerks back. “What? But that’s dangerous!” he yells. “I can’t believe you did that!”

I tip his head back down so he can hear me. “Be mad at me later, Baba, but you’ve got to help before it’s too late. I’ve hidden some . . . writing inside a pillow on the porch swing. Could you ask the workers to find it?”

He claps a hand to his forehead. “Ay, Bhagavan!”

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

But he goes over to the man who stopped me. They talk, and after raising a hand to pause the machines, the man disappears. Baba waits by the fence. I imagine big boots walking to the house, long strides covering ground faster than Ma’s or mine. After what seems like forever, the man returns. My stomach sinks; he’s shaking his head.

When they’re done talking, Baba comes back. “Sorry, Pandu, but there’s no swing on the porch. The owner had everything moved off the property—furniture, books, papers—early this morning. I thought I saw a moving truck from my study window, but didn’t pay much attention.”

I swallow. Hard. “Are you sure? If I could go over there myself and look, maybe—”

“It’s a demolition site now. It was dangerous before, and it’s even more so now. Let’s go home.”

The roaring starts up again. Baba takes my hand and leads me back across the street. My heart is pounding along with the machines. The noise is not as loud in the front hall once the door is closed, but the bulldozers still sound like artillery.

Ma’s handwritten letters.

My letters to her.

And that photo I loved so much.

Gone.

Thanks to Mitali and to Chantal Gersch and the folks at Macmillan Children’s Publishing Group for agreeing to both an interview and an excerpt today. Hope in the Valley is on shelves everywhere, July 11th.

Filed under: Excerpts, Interviews

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

The 2024 Ninja Report: Bleak

Review| Agents of S.U.I.T. 2

Navigating the High School and Academic Library Policy Landscape Around Dual Enrollment Students

Read Rec Rachel: New YA May 2024

ADVERTISEMENT