Finding Answers: Leonard Marcus Looks at the Creation of Picture Book Worlds and Discusses the Global Children’s Illustration of PICTURED WORLDS

Sometimes a person finds themself in another country and they want to cast off all connections to their home country. For example, this past March I was in Bologna for the Bologna Children’s Book Fair and while I was perusing the bookstore they have on the conference floor I saw an amazing title. The store looked like this:

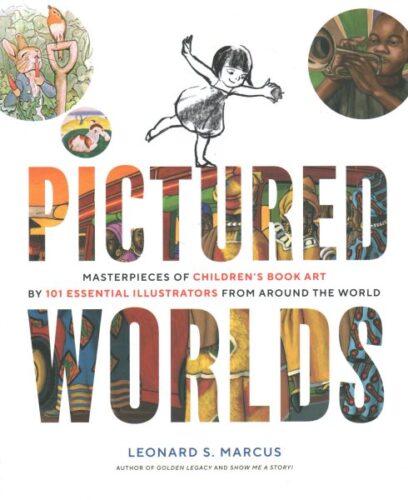

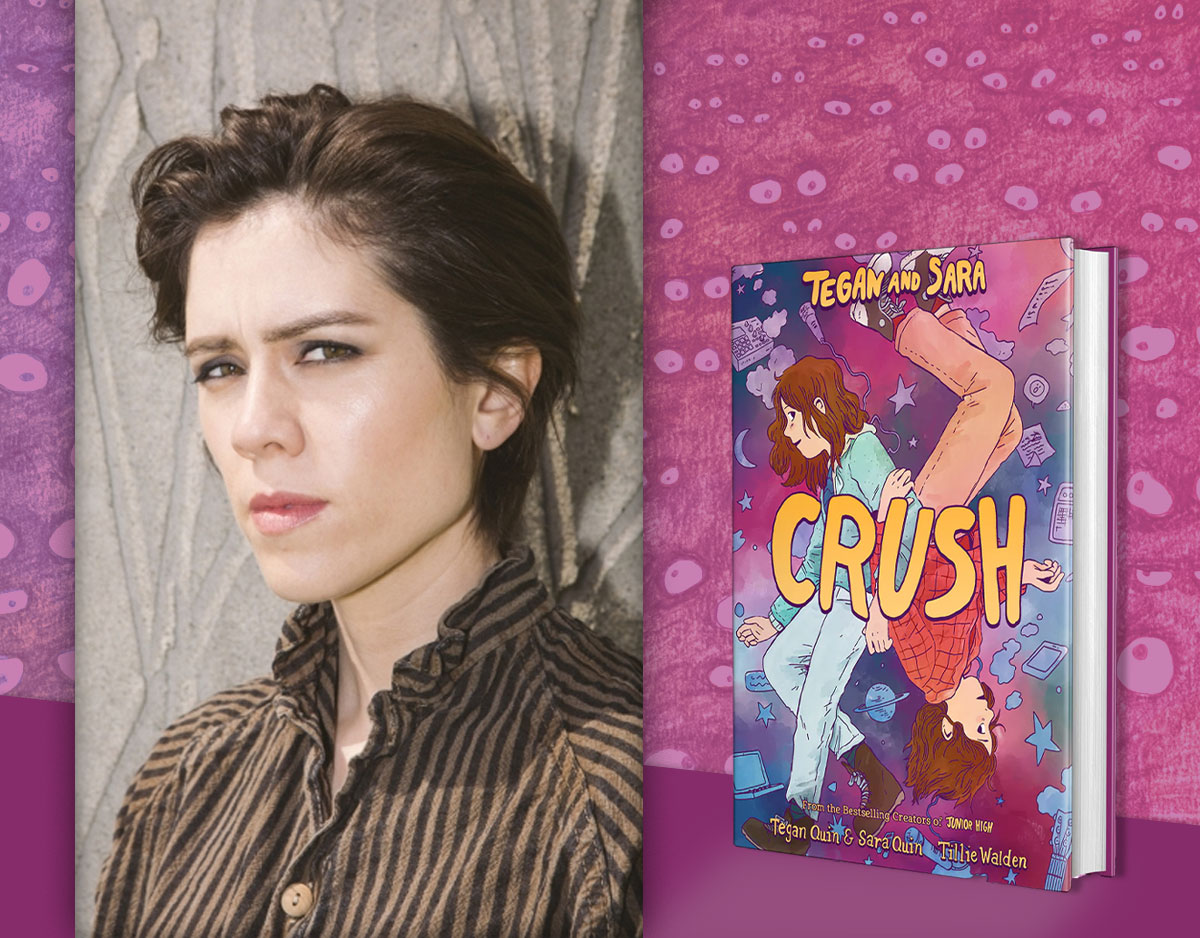

The book, like this:

Ist not that beautiful? It may have been American in origin, but for once I didn’t care a jot. A new Leonard Marcus book is, by definition, a happy event (and I have Minders of Make-Believe on almost permanent display in my library’s Staff Picks section, so you know I put my money where my mouth is). And this latest one is a a fascinating encapsulation of 101 illustrators worldwide.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Here’s the official Abrams description:

A lavishly illustrated, large-format reference book highlighting the work of 101 top children’s illustrators

The illustrated children’s book came of age in the 18th century alongside the rising middle-class demand for economic and social advancement. Inspired by philosopher John Locke’s prescient insights into child development, London publisher John Newbery established the first commercial market for illustrated “juveniles” in the West, and the impact of the model he set for books tailored to the interests and capabilities of young readers has spanned the globe, spurring higher literacy rates, cultural enfranchisement, and a better life for generations of children.

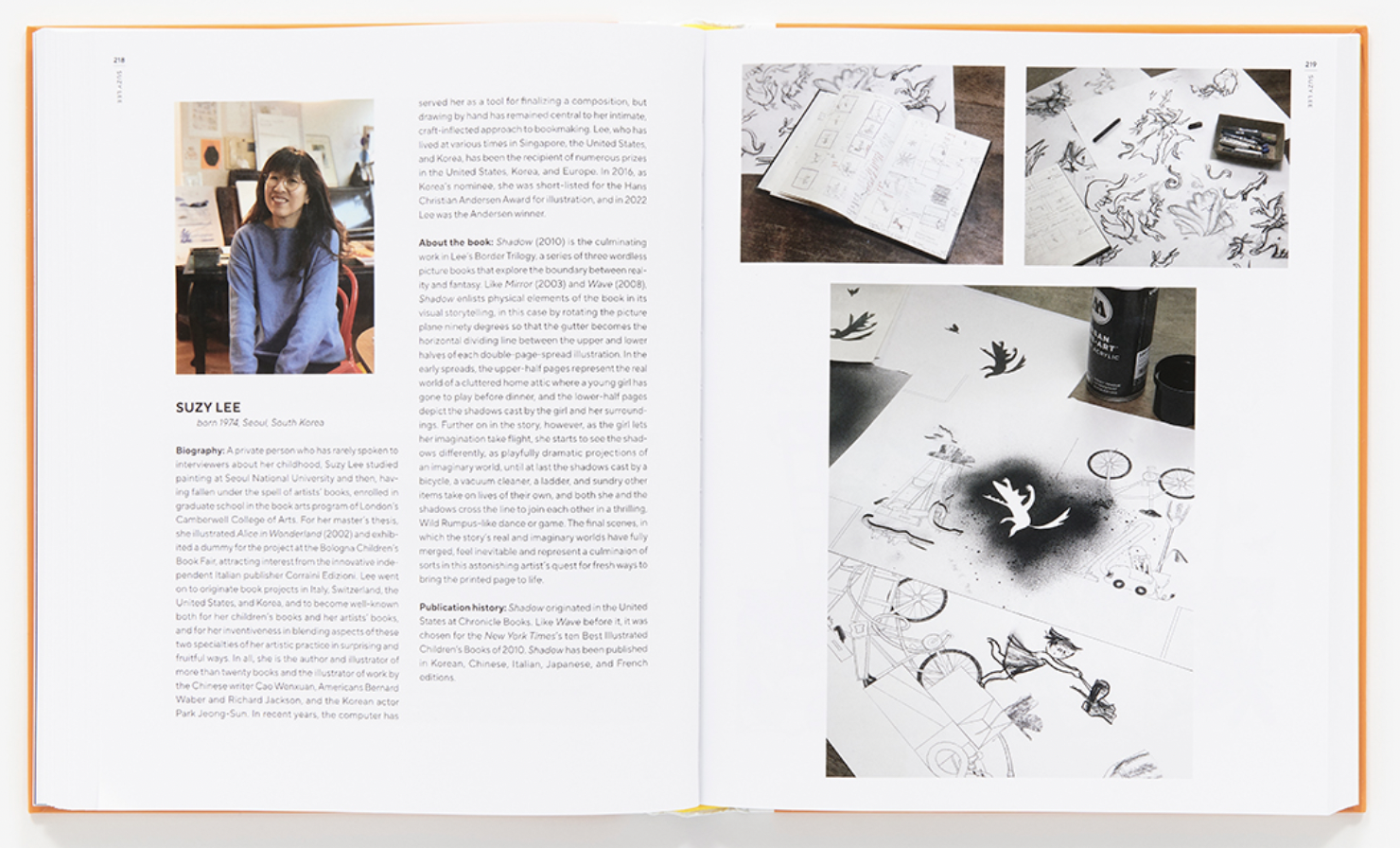

In Pictured Worlds, renowned historian Leonard S. Marcus shares his incomparable knowledge of this global cultural phenomenon in the definitive reference work on children’s book illustration. The author of more than 25 award-winning books, Marcus here highlights an international roster of 101 artists of the last 250 years whose touchstone achievements collectively chart the major trends and turning points in the history of children’s book illustration. While some illustrators explored in this lively volume (John Tenniel, Maurice Sendak) have become household names, Marcus’s wide-ranging survey also shines a light on several lesser-known figures whose unique contributions merit a closer look. The result is a sweeping chronicle of a vibrant art form and cultural driver that has touched the lives of literate peoples everywhere. Over 400 illustrations showcase landmark books from Great Britain, the United States, France, Germany, Austria, Italy, Sweden, Czech Republic, Russia, Japan, China, Korea, Bulgaria, Argentina, Cameroon, and more.

Each illustrated entry is comprised of an artist’s biography and career overview and a deep-dive look at a pivotal book and its legacy. Featured books include Ivan Bilibin’s The Golden Cockerel, Leo Lionni’s Inch by Inch, Richard Doyle’s In Fairyland, Kveta Pacovská’s One, Five, Many, Helen Oxenbury’s We’re Going On a Bear Hunt, Mitsumasa Anno’s Anno’s Journey, and Zhu Cheng-Liang’s A New Year’s Reunion, as well as the books that introduced such iconic characters as Alice, Max, Struwwelpeter, the Little Prince, and Winnie-the-Pooh. At once a celebration of illustrated children’s books and an essential reference work, Pictured Worlds encapsulates, in the author’s words, “the special nature of the illustrated children’s book as a cultural enterprise that is at once a rewarding art form, a bridge across cultures, and a ladder between generations.”

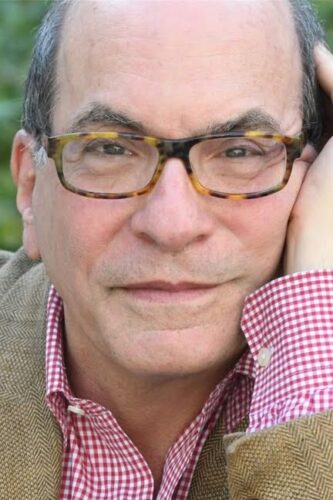

Leonard was able to sit down and talk to me about the work itself:

Betsy Bird: Leonard, thank you so much for speaking with me about PICTURED WORLDS. You’ve done any number of children’s book retrospectives over the years but with the sheer size and girth of this title I feel you’ve truly created what PW dubbed, “a definitive reference work” on the subject. Could you tell us a little about the origins of this book. How long have you intended to create a title of this scope and how long was this book in the making?

Leonard Marcus: PICTURED WORLDS was many years in the making. Around 2012, Peter Mayer, the legendary publisher who, after stepping down as global head of the Penguin Group devoted himself to running the art-forward Overlook Press, loved illustrated children’s books and asked me to write a book on the subject. He envisioned a hefty, wide-ranging, heavily illustrated international survey, a book that would look at–and beyond–the Anglo-American tradition and delve into obscure but historically significant achievements as well as the justly famous ones. I could hardly believe my ears but soon realized Peter meant every word of it. A friend at the time said, “Oh, you’ll be able to write that book in your sleep,” but as I got down to work it felt for a long time as if I could either sleep OR write it but maybe not do both: there was so much to know and understand. Sadly, Peter died in 2018. Abrams acquired Overlook and fortunately my book project made it through the transition, as well as the pandemic and world paper shortage, and was put in the care of my excellent editor Chelsea Cutchens, for all of which I am extremely grateful.

By 2012, I had been to the Bologna Book Fair once or twice and was keenly aware that we in the US never see a large percentage of the children’s books published each year around the world. As big as our publishing industry is, it represents only a fraction of the whole. Knowing this raised basic questions about how the publishing industry works from country to country and, apart from the economics of globalization, what cultural differences may also be responsible for some books “traveling” better than others from culture to culture. PICTURED WORLDS became an ideal opportunity to reflect on these questions and find some answers.

BB: On a related follow-up question, what did your research process look like?

LM: Over the years, I have written many articles, essays, and reviews about children’s books from other countries, and interviewed scores of artists, writers, and editors in the field whose careers reached back as far as the 1930s. So, I had begun my research for PICTURED WORLDS long before I knew where it was all headed. Happening on to picture books by the Japanese artist Mitsumasa Anno, for example, at the Cloisters Museum bookshop in New York during the late 1970s, and being blown away by Anno’s artistry and originality, was one of the experiences that inspired me to write about children’s books in the first place. I later had the thrilling chance to interview Anno. At one point, when he could not find the words to describe for me an episode from his grade-school years, he even sketched a few drawings as we talked.

Keeping an eye out for special picture books has been a favorite pastime during my travels. I learned about the Cameroon-born artist Christian Epanya during a visit to the Musée du quay Branly in Paris and about the Argentinian artist Isol on a trip to Stockholm. Writing a reference-book entry about Heinrich Hoffmann led me deep into backstory of the German classic Struwwelpeter, or “Slovenly Peter.” (Who knew that Mark Twain had been the book’s third English-language translator?) At ALA one year, Dorothy Briley, Clarion’s long-time publisher and an ardent IBBY supporter, handed me a copy of the Clarion edition of one of Czech artist Kveta Pacovska’s amazing experimental picture books; this was my introduction to another of the artists I later met–and wrote about in PICTURED WORLDS.

For the artists I included from earlier times, there were books to consult (monographs, biographies, and the like) and archives (both here and in other countries) to look to for source material. The internet streamlined many of my searches considerably but of course there were a lot of searches. I enjoy doing detective work, and think I would have made a pretty good sleuth, but research can also be slow-going and frustrating at times.

BB: Well, very much along those lines, you focus primarily on 101 illustrators from around the world, making this book less a question of finding the right names but of cutting them down to a mere 101. I wonder if you could speak a little to the process you underwent to determine what makes any individual artist “essential” in the eyes of this compendium?

LM: I realized from the start that I did not want to stick to just one definition of “essential.” Books can be significant, even history-making, for many different reasons. For instance, in The Diverting History of John Gilpin and companion books, Randolph Caldecott all but single-handedly invented the visual grammar of the modern picture book, showing illustrators from then onward how to “quicken” or animate the images on a page for maximum drama and humor. Caldecott’s greatest contribution was to the form of the picture book, whereas Beatrix Potter’s was to the genre’s attitude to childhood. Potter, who belonged to the next generation and grew up looking at the Caldecott originals her father avidly collected, and in The Tale of Peter Rabbit created what may have been the very first picture book to present childhood mischief as natural, rather than bad, behavior–a huge shift in the understanding of what picture books are there to communicate to young readers.

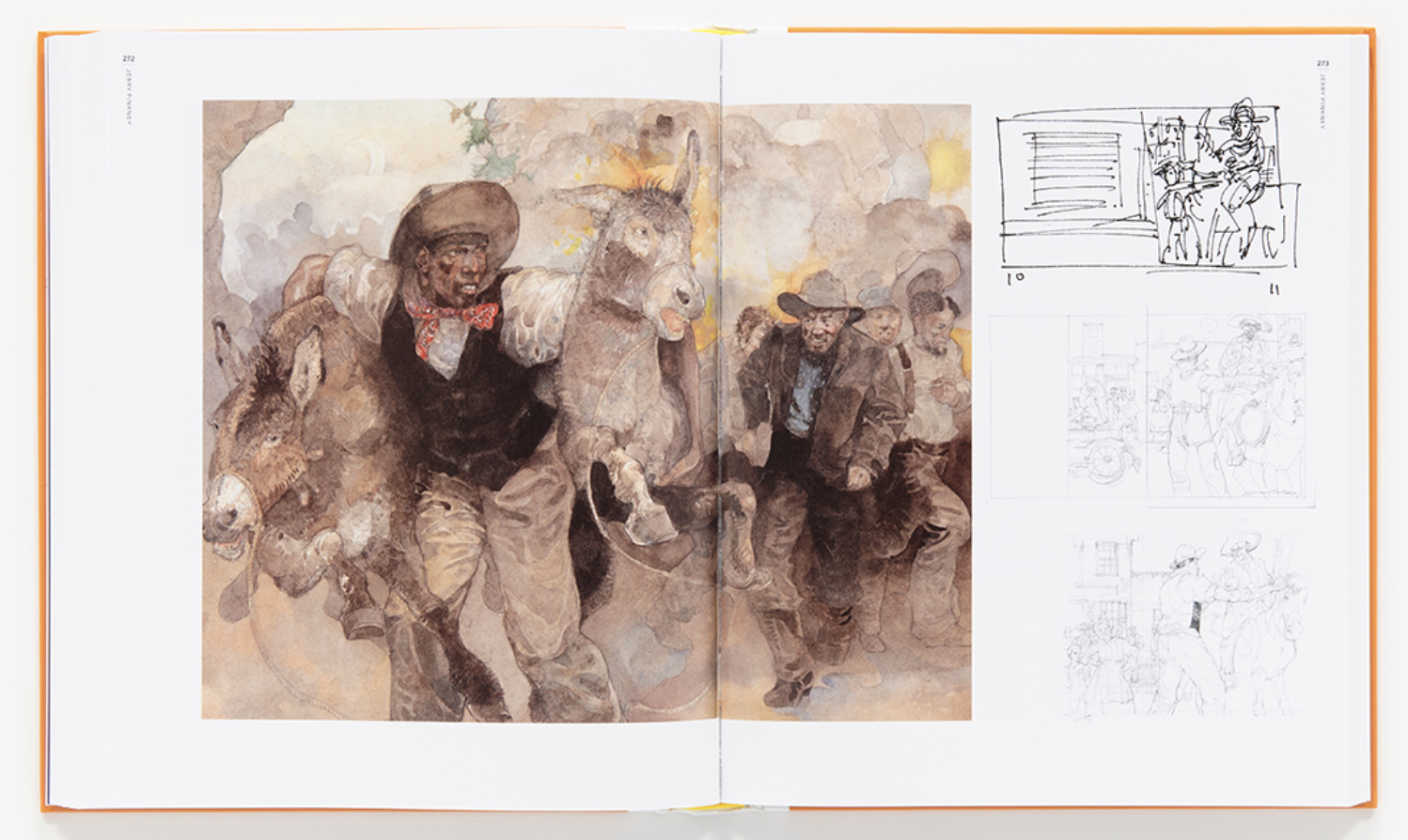

In the late 1800s, illustrated gift books became a major category of children’s book publishing and I thought it would be of value to let readers follow its development cross-culturally in essays devoted to Ivan Bilibin (Russian), Lothar Meggendorfer (German), Arthur Rackham (English), Edmund Dulac (French/English), Howard Pyle and N.C. Wyeth (American), and others.

I also chose key examples of changes in genre audiences and definitions. Goodnight Moon was created with children in mind who were thought by many in 1947 to be too young for any kind of book. Chris Van Allsburg’s Jumanji and David Wiesner’s Tuesday epitomized a relatively new kind of sophisticated picture book aimed at readers who were as likely to fall outside the traditional picture book age range as within it.

So, these examples will give some idea of my thinking about the final selection.

BB: To those that note that you’ve not included every nation on this lovely globe, it is worth mentioning that there are a great number of countries that have not yet made children’s literature a cornerstone of their own publishing industries. You allude to this a bit in your introduction but what are the hallmarks of those countries that have discovered the benefits of creating an environment friendly to children’s book publishing?

LM: The most common pattern is for children’s book publishing to thrive in countries with a rising middle class–where large numbers of parents are ambitious for their children’s future and see literacy as one of the keys. I was fascinated to learn that at almost the same time that eighteenth-century London printer-publisher John Newbery was establishing a commercial market for illustrated children’s books in England, a similar effort was in progress in another great commercial city half a world away: Edo (now Tokyo), Japan. The most spectacular recent example of a children’s publishing industry developing in response to middle-class demand is China, which had nothing resembling a children’s literature of its own until the start of the new millenium, when the door opened wide to Western cultural influence and an intensive effort to “catch up with the West,” as it was described to me on a visit there, began in earnest. I was surprised in 2013 when I learned that my book Dear Genius: The Letters of Ursula Nordstrom, was going to be published in China the following year but I soon realized why–and found myself on a plane to Beijing to speak to an audience of hundreds of Chinese publishers about America’s visionary publisher for young people and answer questions like, “What was Maurice Sendak really like?” and “What kinds of children’s books are most popular with American parents?”

A second impetus to children’s book publishing has to do with nation-building. Not long after the end of the American Revolution, Noah Webster produced children’s books designed to teach the young citizens of the new republic not only how to read but also how to spell like an American. (It was Webster who took the “u” out of “honour,” arguing that his simplified spelling was less pretentious and therefore more democratic in spirit.) Some of the most graphically spectacular picture books of all time were published in the Soviet Union in the years immediately following the Russian Revolution, their purpose being not only to get young people interested in books but also to feel a sense of excitement about the new society their parents hoped to create with their help.

BB: Aww. I remember going through the archives of NYPL with you, looking at those Soviet Union publications, back in the day. Now in this book’s introduction you make great mention of children’s book art museums that have proliferated around the world after the first museum of picture book art (The Chihiro Art Museum in Tokyo) was established. How many of these have you yourself visited? And what is the value to the American children’s book enthusiast to taking in illustrations from countries beyond our own borders?

LM: I’m a founding trustee of the Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art (Amherst, MA) and have been an adviser to both of the other US museums: the Mazza Museum (Findlay, OH) and the National Center for Children’s Illustrated Literature (Abilene, TX). I’ve been to all three. I have also visited the Chihiro Art Museum (Tokyo) and the Seven Stories National Centre for Children’s Books (Newcastle-upon-Tyne, UK). I still have several more to go!

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

As for the value of seeing the work of children’s book artists from other cultures, I think it’s comparable to the value of any form of foreign travel. In a culture other than one’s own, things we take for granted are apt to be understood and presented a bit differently. In the US, where we prize individualism as a value, illustrators tend to keep a story’s main character in the foreground and center stage. But in Japan, for instance, where community cooperation is a higher priority, that might not be the case. It can be refreshing and thought-provoking to realize that there are such different approaches to visual storytelling–and to living. Also, there are a great many illustrators from around the world whose work is so distinctive that it is worth experiencing on its own terms: the whimsical yet convincingly realistic elfin fantasies of Sweden’s Elsa Beskow and England’s Richard Doyle; the ingenious and surprisingly low-tech popup creations of Czech architect turned children’s book artist Vojtech Kubasta; the bell-clear picture book graphics of Russian/French illustrator Nathalie Parain; to name just a few. In recent years, computer graphics technology has pushed illustration toward a flat, graphic style that often reads as culturally neutral and visually bland. For that reason and others, there has probably never been a better time than now for children’s book artists in particular to look to the illustration art of the past, and to the art from other countries, for inspiration.

BB: And finally, I’ll end on an unfair question. The book is of 101 international artists. If the book were, instead, 102, who would have made that last mention?

LM: As you’ve suggested, in an ideal world PICTURED WORLDS would have featured many more than 101 artists both past and contemporary. But even a big book can only be so big and still work from a publishing standpoint. So, I’ll just mention one artist I am especially sorry not to have been able to include, in his case because we were unable to locate the copyright holder: Vladimir Lebedev, who in 1926 illustrated a post-revolution-era Soviet picture book called Circus with a text by Samuil Marshak. Lebedev’s brightly hued, avant-garde building-block graphics are a joy to behold and to me they represent the highpoint of an idealistic moment in book making for children that Lebedev further helped to bring about in his role as one of Soviet-era publishing’s leading art directors. Picture books like his were printed in paperback editions at affordable prices and went back to press often. Lebedev was apparently so passionate about his work that he revised the illustrations of Circus from one printing to the next. Don’t you love that? Picture book people tend to be that devoted to their art and audience, and I think just about any of the illustrators I wrote about would have jumped at the chance to do the same.

I absolutely love that we ended with Lebedev in our interview. What better way to conclude than to invoke an artist so dedicated to the craft of picture book illustration?

I wish to thank, profusely, Leonard Marcus to submitting to my questions today. Thanks too to Gabby Fisher and the folks at Abrams for setting this up in the first place. Pictured Worlds is available now for purchase wherever fine books are borrowed or sold. Take a look. Expand your mind.

Filed under: Interviews

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

The Origins of THE WILD ROBOT with Peter Brown

Kagurabachi, vol. 1 | Review

The Seven Bills That Will Safeguard the Future of School Librarianship

Cindy Crushes Programming: Anime Club, by Teen Librarian Cindy Shutts

Gayle Forman Visits The Yarn!

ADVERTISEMENT

I MUST read this. I love Soviet-era illustrations (and the propaganda posters of the era are amazing) and Marshak’s books. Wonderful!

What a fabulous interview! Thank you, Betsy!