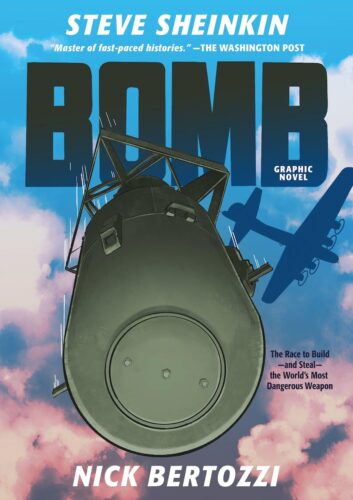

Dropping the Dual Interview Bomb: Steve Sheinkin and Nick Bertozzi Discuss Their Graphic Novel Adaptation

I mean, I get it. You attain a certain age and suddenly you understand why old codgers feel perfectly inclined to sit in their rockers and rail at the young ‘uns on how good they have it these days. I imagine I’ll the same before too long. Toothless. Crochety. Occasionally spitting sunflower shells into a cup by my side as I yell at the children playing in the yard across the street about how when I was a kid we didn’t have all these fancy, accurate informational books you children seem to have today. No, sir! Our books mixed fact and fantasy together like crazy and who knew what was true or not? Not like today with your lavish backmatter and timelines and bibliographies and cited sources.

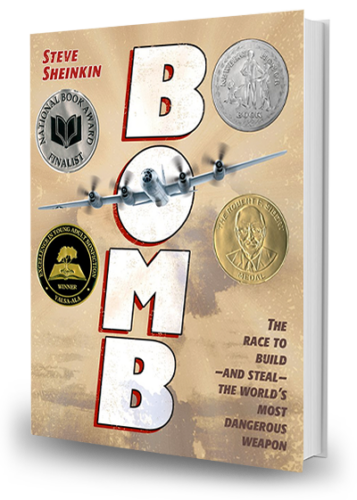

And what, may I ask, is the book that typifies all of this? Why that would have to be Bomb: The Race to Build – and Steal – the World’s Most Dangerous Weapon by Steve Sheinkin. Boy, that book won everything from a Newbery Honor to a Sibert Medal to a National Book Award Finalist position to a YALSA Award for Excellence in Nonfiction … and more!

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

That’s another thing you kids today don’t appreciate enough! Not only do you get Steve Sheinkin books, now you get comics adapted FROM Steve Sheinkin books! Whole new ways of reaching readers, they are!

Yes, if you hadn’t heard the news yet, it’s true. BOMB has been adapted into a graphic novel format thanks to the illustrative stylings of one Nick Bertozzi. Out today, the book brings Sheinkin’s story to life in a whole new fashion. And now that I’ve remembered that I am not, in fact, a toothless old reprobate (yet), I’m going to interview both men on the book and all that its adaptation entails:

Betsy Bird: Steve! Lovely to talk with you a bit about BOMB in its new iteration. We’ve seen young reader adaptations of nonfiction for adults but I’m wracking my brain and coming up short trying to think of graphic novel adaptations of nonfiction written for kids in the first place. Who came up with the idea of making BOMB into a comic? And why?

Steve Sheinkin: Thanks so much for doing this, Betsy! The idea for the graphic adaptation actually came from my publisher, Macmillan—from Jennifer Besser, and my longtime editor, Connie Hsu. Luckily, I had the remarkable wisdom and foresight to say, “Yeah, that sounds like a cool idea.” In terms of why… Well, I love comics and it was easy to start imagining how BOMB’s story of science, spies, and commandos could work well in the graphic novel format.

BB: And that meant getting Nick Bertozzi involved. Nick, thanks so much for answering some of my questions here as well. Truth be told, I’m a little curious about how you got involved with this particular project with Steve. How did you come to work on this? And were you familiar with BOMB before or was it new to you?

Nick Bertozzi: Connie Hsu, the fantastic Editorial Director at Roaring Brook Press, an imprint of Macmillan Children’s Publishing Group, asked me to draw BOMB, and though I hadn’t read Steve’s prose book, I was very excited by his nuanced and exciting take on the history. I was more than a little nervous to say yes because I knew I’d have to draw 250 pages of fedoras and I’d had a similar experience drawing bowler hats in a Houdini graphic novel. But Steve’s ending was so good I had to sign up.

BB: I get that. And speaking of that Houdini book, while I’ve seen you do a fair number of American history comics over the years, this is the first (and I admit that there may be others) where you adapted a children’s author’s nonfiction book into a comic intended for the same audience. You’ve adapted authors before (Pearl Buck’s The Good Earth comes to mind) but this seems unique. Was the process in adapting this book the same as for other books you’ve done in the past, or did it differ in some significant way?

NB: Steve wrote a graphic novel script for the adaptation which made the process very easy, especially since he writes in such a visual way. THE GOOD EARTH took much longer since I was compressing a 400-page book into 120 comic pages. I spent a few months just working on the script. I had to throw out entire chapters. I did try hard to get as much of Pearl Buck’s descriptive prose into the art.

BB: Let’s talk a little about that script. Steve, what have been some of the advantages of the comic version of this story versus the book itself? With Nick’s comments in mind, were there any passages that came across more clearly thanks to the visuals? Were there passages that were particularly difficult to adapt?

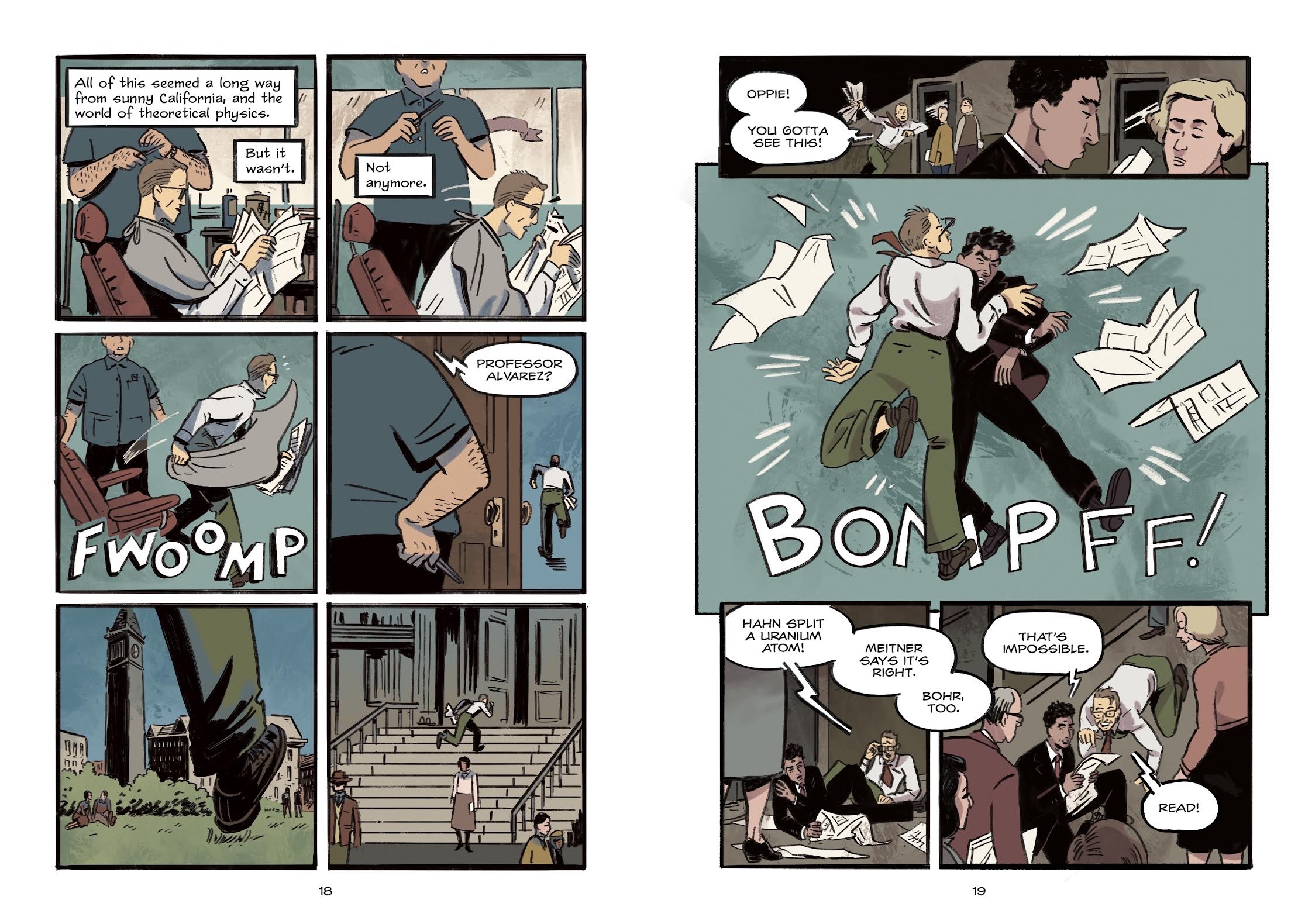

SS: The number one advantage is the chance to zero in on scenes in a way that’s not always possible with narrative nonfiction. I mean, sometimes we know these two people had this tense, high-stakes argument, but we don’t know what they said. With comics, I get to write the whole scene. I get to make up dialogue! Those hard-boiled detective scenes were especially fun to write.

Another advantage of comics is how useful visuals are when introducing scientific ideas—radioactivity, isotopes, things like that. Complex stuff, but much easier to grasp when you can see it. Turns out I’m a visual learner. That hadn’t been invented when I was in school, but it would’ve explained a lot.

BB: It’ll also make the book so much more accessible for today’s visual learners as well. But before we move away from this, I want to get Nick’s perspective on this adaptation process. Nick, did BOMB translate to a comic format easily or were there some rough patches in figuring it out?

NB: The 20-page commando raid section of the book took an exceedingly long time because I’d never drawn an action scene that took place in so many locations–an airplane, a winter mountainscape, a forest, a cabin, a ravine, a bridge, a heavy water factory, a boulder, a fence– featuring so many characters. And I always like to make sure every article of clothing or location is well-researched so the reference-hunt alone ate up time. Irene Yeom colored the heck out of the book and that section particularly.

BB: Can’t even imagine it. Steve, let’s look at some logistics on your end. I know that you’ve had a fair amount of experience with comics, between your own Rabbi Harvey series (to say nothing of the “Walking and Talking” comic interviews you conducted with different children’s book creators on my own blog over the years). Did you single-handedly figure out how each panel on each full-page layout would look for the new version of BOMB? Did you collaborate with someone instead? What was the process here?

SS: It’s true, I like to draw as well as write. But let’s be honest: I don’t have the chops to draw something like BOMB. I wrote the script in specific panels and pages. For each page, I specified what happens on Panel 1, Panel 2, etc. I could see it in my head—and sometimes sketched storyboards to check the compositions—but I knew we needed a really great artist to bring it to life. When Nick came onboard, we agreed that he’d have the freedom to combine panels or rearrange spreads. So it’s not only his amazing art but also his vision—almost like film editing—that makes the book what it is.

BB: And was there anything you had to cut out of the original book that you really wish you could have gotten into the comic?

SS: The sad truth is, you have to cut a lot to make 250 pages of text fit into 250 pages of comics. Just to give one example: Mo Berg. He’s the retired baseball player turned spy who was sent on this stranger-than-fiction mission to assassinate Werner Heisenberg, a great German physicist. I put it in the script, and it was in Nick’s early drafts too, but the story just wasn’t working with the more streamlined pacing of the comic. Mo probably needs his own book. Someone should really see to that.

BB: I’m up for reading that! Now, Nick, I don’t want to shy away from the amount of work you put into this as well. Tell us a little bit about your process. When you’re laying out the panels and figuring out the initial rough sketches, do your first drafts resemble the final product or do you tinker a lot with how to tell the story as you’re putting it down?

NB: For a long historical graphic novel like BOMB, I use InDesign to turn the script into panels, dialogue, narration, and staging, a technique I picked up from Alison Bechdel via Jessica Abel. This process helps to figure out where I can combine panels or where I need to stretch out a scene. The commando raid is very compressed to match the speed of the content whereas the first bomb test scene is stretched out a bit to underscore the scale of the event. From there, it’s nothing but tinkering throughout the rough penciling, finished penciling, and inking stages. I have to mention that Connie, and Steve gave the most-insightful, most-helpful notes I’ve ever received on a graphic novel. They pulled my best work out of me and I’m very grateful for the experience.

BB: And I’m grateful that you just name dropped both Alison Bechdel and Jessica Abel. Love them both! Steve, I just have to ask it – is there any chance that we’ll be seeing other books of yours getting the same treatment as BOMB here? Because I, for one, would love to see the opening sequence of FALLOUT put into panels.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SS: In short, I plan to do lots more. Yeah, that hollow nickel sequence in FALLOUT is meant to feel like the opening scene of a movie, so it’s nice to hear that you can see those images. I’m also thinking (as I often am) about Benedict Arnold. I mean come on: nonstop fighting, adventure, spying, romance. He’s America’s original loose-cannon action hero—born to stalk the pages of his own comic!

BB: I personally know some children’s librarians who would be very very happy if Benedict were to show up once again on their shelves. And finally, Nick, what’s next for you? What do you have coming out, for kids or adults?

NB: I’ve started working on a pitch for a graphic novel adaptation of Louisa May Alcott’s HOSPITAL SKETCHES. Though Alcott only served as a nurse in the War of Rebellion for a few short weeks, her prose is so descriptive and her sense of humor is so strong. And I have a pitch for a kids graphic novel about the cleanup of the Gowanus Canal.

Thank you for the terrific questions, they were very fun to answer!

BB: You kidding? You guys are the best! Hope to see all your books, no matter what they are, in the future soon.

Bomb, the graphic novel, is literally out today on shelves all over this great nation of ours. Pick it up and hand it to those juvenile history buffs just itching for more finely rendered stories. Many thanks to Morgan Kane and the folks at Macmillan for setting up these interviews. And thanks, of course, to Steve and Nick for so patiently answering all my myriad questions.

Filed under: Interviews

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Notes on March 2025

Halfway to Somewhere | Review

Fifteen early Mock Newbery 2026 Contenders

When Book Bans are a Form of Discrimination, What is the Path to Justice?

Take Five: Recent Middle Grade Nonfiction

ADVERTISEMENT