Review of the Day: Shuna’s Journey by Hayao Miyazaki

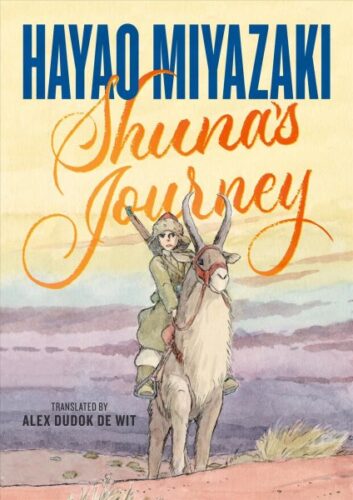

Shuna’s Journey

By Hayao Miyazaki

Translated by Alex Dudok de Wit

$27.99

ISBN: 9781250846525

Ages 9-12

On shelves now

In the pantheon of Miyazaki fans you have to rate yourself on a kind of scale. There are, after all, folks out there that make veritable pilgrimages to places like the Ghibli Museum, Mitaka in suburban Tokyo or the café Kodama in Nagoya, Japan. Then there are folks who’ve never even seen a Miyazaki film and can’t figure out what the fuss is all about. Myself? I fall fairly squarely in the middle. My first Miyazaki was Howl’s Moving Castle and mostly that was just because it was based on a Diana Wynne Jones book I liked. In time, however, I’d see other movies like Kiki’s Delivery Service, Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, and my personal favorite (which I’ve seen several times) “Castle in the Sky”. So I’m in a fairly interesting position to read and gauge a graphic novel of his which has been overwhelmingly successful in other countries for years but is only just reaching the States now. Shuna’s Journey, as is explained by translator Alex Dudok de Wit, precedes much of what we now consider to be Miyazaki’s seminal work. Loosely based on a Tibetan folktale, the book was originally published in 1983, two years before the launch of Studio Ghibli. Reading it now, it’s this epic, ancient, futuristic, sprawling storyline full of gods and slaves and ancient decaying civilizations. Remarkably it acts as a kind of Intro to Miyazaki in and of itself. The real question that remains, however, is how well it compares to the comics of today. Does it have what it takes to be a graphic novel for kids in the 21st century?

Copyright © 1983 Studio Ghibli

All rights reserved.

First published in Japan by Tokuma Shoten Co., Ltd.

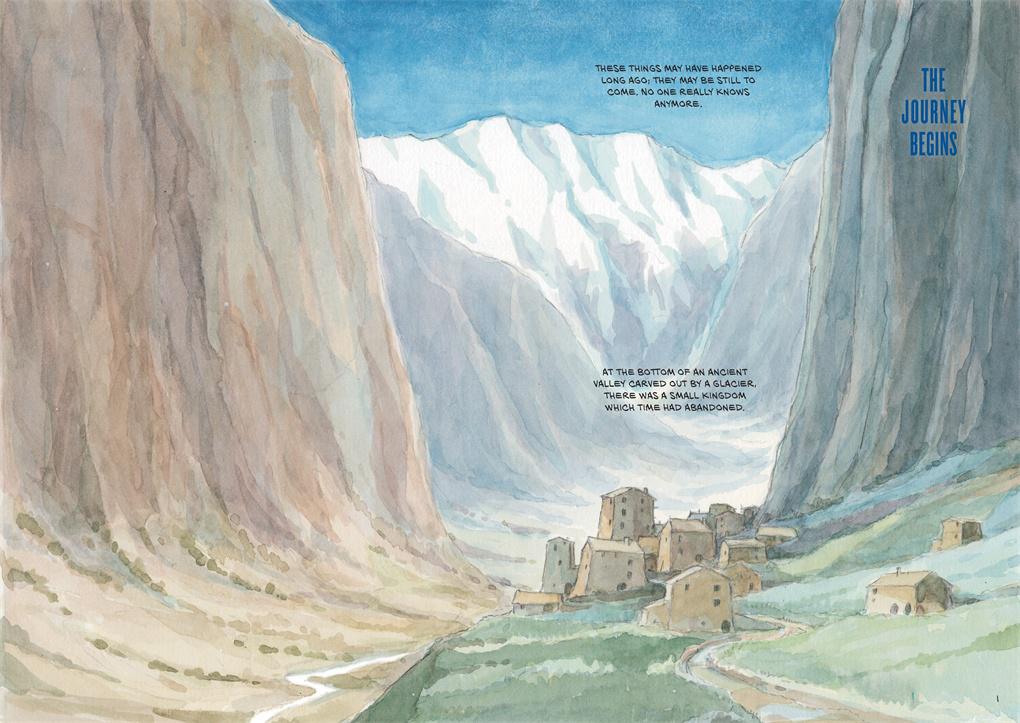

“These things may have happened long ago; they may be still to come. No one really knows anymore.” In this tale a small kingdom exists in an ancient valley, just scraping by. There’s hardly enough food to feed anyone. Here a prince by the name of Shuna lives, and one day, after rescuing a stranger, he learns of a grain that would feed his people indefinitely. The old stranger never found the food, but Shuna is invigorated by the quest. Against the advice of the elders he sets off to see the world and find the grain. Along the way he encounters slavers, a strange moon that travels across the sky at great speeds, kindness, cruelty, and at last a strange land where attaining knowledge means losing everything you have.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

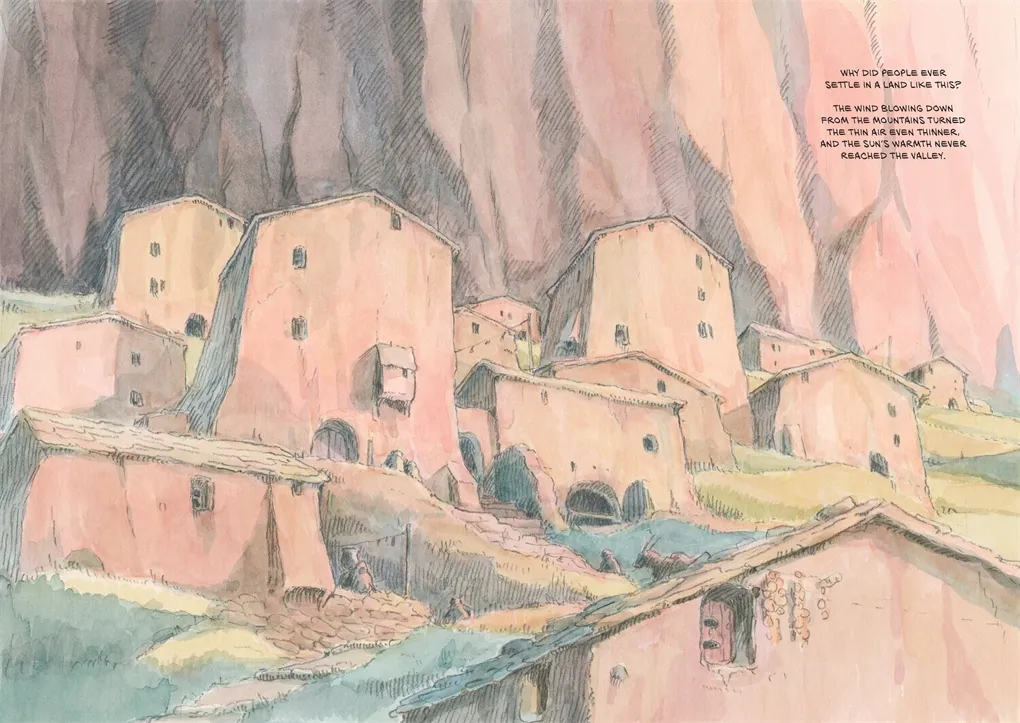

Epic. Definition: extending beyond the usual or ordinary especially in size or scope. Miyazaki has never been a man afraid of the big picture. Indeed, his films have a tendency to go big or go home. And clearly, after reading Shuna’s Journey this was always the case. I love a children’s book that makes big swings and it doesn’t get biggier or swinginger than this! First and foremost, there’s the story itself. In his Afterword, Miyazaki explains that the Tibetan folktale he based his story upon may have connections to reality. After all, the tale is all about bringing a cereal back to your country. Miyazaki notes that barley is a staple in Tibet but originated in West Asia. From such simple beginnings, though, he crafts an otherworldly reality that’s just as likely to yield wonders as horrors. Late in the book it starts to resemble nothing so much as Jordan Peele’s film Nope, albeit with more jolly green giants getting eaten alive by critters. Then there is the art, which Miyazaki painted himself. They look like watercolors and he just seems to be having such fun with this world. Ancient crumbling statues are the name of the game, but he’s just as adept at nature and architectural details as well. A second read and I picked up on details I might have missed the first time around. There are quite a few layers to the whole enterprise.

Copyright © 1983 Studio Ghibli

All rights reserved.

First published in Japan by Tokuma Shoten Co., Ltd.

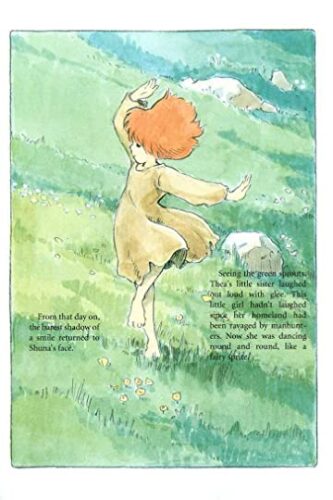

The world constructed here is strange and adding to that strangeness is the fact that Shuna goes on an unusual hero’s journey. To be perfectly frank, I’m not used to stories where you follow one character for 110 pages and then the focus switches to someone else for the remaining 34. The choice made here is to render Shuna utterly helpless for the final act of the storyline. Because he did an act of kindness early on, he is saved by those saved by him. Early in the story Shuna saves a girl named Thea and her younger sister from the manhunters. Later, when he has stolen some of the golden grain, his memory, speech, everything really is taken from him and it’s Thea that has to care for him until he is better. Thea is, herself, a strong character who can take care of herself and her sister very well once they’re on their own. As such, you don’t mind the shift to her perspective when it happens. It’s unusual but not unheard of and fits the folktale feel of the endeavor.

Cultural appropriation is something we Americans understand in a fairly limited sense. We get it if we’re already pretty well and truly familiar with the cultures doing the appropriation. When we aren’t, we get a touch confused. Shuna’s Journey is a rather good example of this. Reading this as a Yank it hadn’t really occurred to me that a Japanese creator taking a Tibetan folktale could be read as appropriation. Certainly this is, as the very first line of the book says, a story that could either be the past or the future, depending on how you prefer to see it. There are also elements of Tibetan culture, but it didn’t feel at any point that the creator was doing much more than taking the place more than a jumping off point for his own very different vision. Still, it’s something to take into account, even as you read.

Copyright © 1983 Studio Ghibli

All rights reserved.

First published in Japan by Tokuma Shoten Co., Ltd.

In his note at the end of the book, translator Alex Dudok de Wit says of Miyazaki’s book that, “it is unique in his career: He has never produced another standalone emonogatari book. Nor, I think, has he ever told a story as beguilingly strange as this one.” The words “beguilingly strange” are absolutely perfect. There’s hardly any other way to describe this book. It reads like a manga, from right to left, but as de Wit points out it prefers captions to speech balloons. He calls it an “illustrated story”, though I think “graphic novel” is probably the most accurate description at this time. Whatever you want to call it, there’s a feel you get after reading this book that is entirely its own. Eerie and unnerving, yet at the same time filled with beautiful and even calming moments, this is a book to entice those that have never seen a Miyazaki film and to enthrall those already under his spell. I’ll say it again. “Beguilingly strange”.

On shelves now.

Source: Final copy sent by publisher for review.

Filed under: Best Books, Best Books of 2022, Reviews, Reviews 2022

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Zachariah OHora on PBS

Girlmode | Review

The Seven Bills That Will Safeguard the Future of School Librarianship

Read Rec Rachel: New YA Releases for November and December 2024

Gayle Forman Visits The Yarn!

ADVERTISEMENT