Wutaryoo? An Old Question Gets a New Look, and an Interview with Nilah Magruder

Like a lot of libraries around the country, my own Evanston Public Library has been trying to figure out the best possible way to conduct an equity audit of our collections. Equity audits are where you take an in-depth, book-by-book look at the collection and determine, ultimately, how many BIPOC voices are represented. One of the factors that might not occur to you initially when looking at picture books is animal characters. Does your library contain more animal protagonists on the whole than BIPOC protagonists? One might think that most animal picture books are written by white authors.

Nilah Magruder enters 2022 with a picture book of her own. And, as you might be able tell from its title, her new picture book WUTARYOO is a sly comment on a question that a lot of BIPOC kids (and, let’s face it, adults) deal with on a regular basis. Given the opportunityu to ask her about the book and the myriad ways of looking at it, I pounced at the chance:

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Betsy Bird: Nilah! Thank you so much for joining me today. I have all kinds of questions about WUTARYOO and no clue where to start. Let’s begin at the beginning then. From what I understand, you’ve worked for Marvel in the past. The shift from comics to picture books seems short (picture books are just large pieces of sequential art, after all) but I know it requires you to tap into a whole different set of muscles. Where did this book come from and how did you come up with it?

Nilah Magruder: I’d been turning over a thought in my head for a long time. That thought was about how easy it is to feel untethered as a Black American, without a sense of “home.” Here in America, we live on stolen land, our ancestors brought here against their will, and to this day so many who live here see us as a blight on society. It is hard to feel at home in America, and yet Africa is not home either. I have no family there. I cannot tell you what nation or even what region my people are from. The only claim I have to Africa is the color of my skin. I was thinking long and hard about this and how to communicate it. It didn’t feel like a particularly safe thought to express, so whatever I did with it, I wanted to be careful. I am not an essayist or historian, but I am a storyteller. This uneasy thought was floating around in my head for years, but I wasn’t really thinking about it when one day I wrote down a few words that felt mythological, folklorish, about a small creature that felt very alone in the world. And suddenly the thought came rushing back to me and everything fell into place.

BB: I’m sure you’re familiar with the Dr. Rudine Sims discussion of windows and mirrors. The idea that kids not only need to see reflections of themselves in the books that they read, but windows only other lives as well. Often, books starring animals are held up as problematic because so many more picture books star animals than BIPOC characters in a given year. People also will say that it is uncommon to find many picture books starring animals, written by Black creators. WUTARYOO stands in answer. When you wrote the book, were you aware of these conversations? How do you feel your book adds to the conversation?

NM: I know the number of books starring animals versus books starring or written about BIPOC, but I was not aware of conversations around Black authors writing about animals. I find that interesting, since my childhood was so informed by animal tales. As a kid in Maryland, my mom often took me to events in Baltimore and Washington, D.C. to hear stories about Anansi and a cast of African animals. My mom told me about the stories of Brer Rabbit and Brer Fox from her youth. I grew up in the country on a track of woodland, what was once a great mid-Atlantic forest before highways and housing developments splintered it to pieces. It feels natural for me to write about animals and nature. My heart has always resided in the wilderness. I knew how to draw animals long before I knew how to draw people. For me, the world of Wutaryoo is a return to my roots.

I think animals are useful storytelling devices. I loved nature as a child, but I also wonder if I loved animal stories because I couldn’t easily relate to stories filled with white characters. Those stories didn’t reflect my experience. The act of reading has always felt like looking through a locked window. I did not know a story could be a mirror until I was an adult. It was much easier to insert myself into the fantastical world of an animal than a white character. Animals are not burdened by human social constructs and prejudice. There is something so comforting and inviting about them. I hope Wutaryoo is a story that children can feel safe and welcome in entering.

BB: What can a picture book with animals do that a more realistic story, say with human kids, cannot?

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

NM: I think there are many ways to tell this story. If I were to tell it with human kids, maybe I’d frame it with the experience of one of those heritage assignments you have in school, where students write reports on their family ancestry. That moment when your classmates are talking about ancestors coming through Ellis Island, and family crests, and centuries of history, and you realize your family’s records only go back to a great grandparent, maybe one or two generations farther if you’re lucky, because for a long time your ancestors were forced to abandon their language, and forbidden to learn to read or write. But this framing makes the context very specific… and there’s nothing wrong with that! I think telling this story with animals makes it more abstract, closer to the “concept” as it exists in my head, less of an allegory and more of a thought experiment. In this way, it becomes a safe place for children to explore the idea of belonging, to take ownership of it in whatever way speaks to them.

BB: Picture books are only just beginning to scratch the surface of issues of identity. How do you feel WUTARYOO speaks to Black identity, belonging, and found families?

NM: The question of identity is always hard because the answer is different for every individual. Wutaryoo is a reflection on my own identity as a Black American. I think it shows one facet of a complicated experience. I wasn’t sure exactly where the story was going when I started it, but what I eventually found myself thinking about is how *new* Black Americans are in the history of human civilization. How we’re still writing our tale… and on an individual level, that’s all any of us are trying to do. Where we start will always be a part of us, but identity is about who we become, as well. And we are social creatures, of course. Home isn’t just a place: it’s the friends and family we take refuge in.

BB: Finally, do you have any future plans to create more books for kids?

NM: Yes! I don’t know when the next picture book will happen; whenever I come up with a good enough idea! My first was How to Find a Fox (Feiwel & Friends/Macmillan), incidentally also a nature book. Currently I’m working on two middle-grade graphic novels: Creaky Acres (about horseback riding, Kokila/Penguin) and Reel Love (about fishing, Random House). I’m also writing a YA fantasy called Hex and Havoc (HarperCollins). I don’t plan to stop writing for kids anytime soon.

BB: Nor would we want you to. Thank you for speaking with us today!

Boy, I would really like to thank Nilah Magruder for taking the sheer amount of time and energy of thought to answer my questions today. WUTARYOO is on on shelves tomorrow (January 25th) so be sure to grab yourself a copy, stat. Thank you too to Sammy Brown and the folks at Harper Collins for setting this conversation up!

And, what the heck, to finish us off, let’s watch Kwame Alexander talking about the book:

Filed under: Interviews

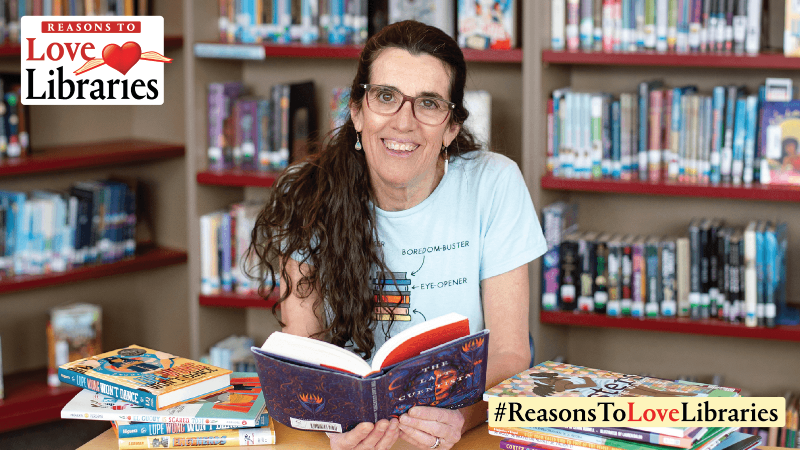

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

The Moral Dilemma of THE MONSTER AT THE END OF THIS BOOK

K is in Trouble | Review

Fighting Public School Book Bans with the Civil Rights Act

ADVERTISEMENT