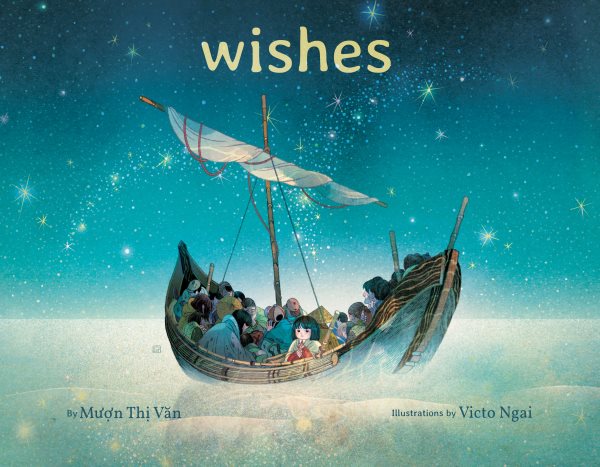

Review of the Day: Wishes by Mượn Thị Văn, ill. Victo Ngai

Wishes

By Mượn Thị Văn

Illustrated by Victo Ngai

Orchard Books (an imprint of Scholastic)

$18.99

ISBN: 978-1-338-30589-0

Ages 6 to 10

On shelves May 4th

It doesn’t happen often, but once in a while I’m faced with reviewing a picture book that makes me feel inadequate to the task. It is a daunting proposition to tell people about books that get everything right. The reviewer’s instincts are to gush, but when the material in the book is serious then that degree of enthusiasm may feel inappropriate. I have been a fan of the author and the artist of Wishes for a number of years, but separately. Mượn Thị Văn wrote the lyrical In a Village by the Sea in 2015. Victo Ngai illustrated the magnificent Dazzle Ships in 2017. They took time off. Did other things. Now, in the year 2021, they come together to produce a book that is perfect in its simplicity. The achingly beautiful Wishes joins such stories as Sugar in Milk by Thrity Umrigar as the immigrant story that both tells an important message and is itself a work of art. In all honesty, I don’t think I can do this book justice when I tell you about it, but I can at least give it my best shot. It deserves only the best.

“The night wished it was quieter.” A young girl peeks out the window at her grandfather. He’s just dug up what appears to be a canister to hold gasoline. Meanwhile, “The bag wished it was deeper” as three women fill it with food, carefully wrapped in leaves. Soon it becomes clear that the woman in the center is leaving. She’s taking her daughter, her son, and a baby (“The path wished it was shorter”) to a boat, into a storm (“The sea wished it was calmer”), under a blazing hot sun (“The sun wished it was cooler”), and finally to a boat of rescue. “And I wished . . . I didn’t have to wish . . . anymore.” A Note from the Author at the end describes how this story is based on when she and her family left in a boat from Viêt Nam when she was a child. They were saved, taken to Hong Kong, and eventually made their way to the United States.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

There is a special thrill that comes when you read a book, enjoy it thoroughly, look up the author’s previous works, and discover that you loved another book they wrote before. Years ago Mượn Thị Văn’s In a Village by the Sea was small and unassuming and its writing was phenomenal. At the time I called it “a melodic visual stunner” which isn’t a terrible way of describing this book as well. Of course, in this book the author has figured out a way to tell a tough story in a creative and entirely effective manner. The subject matter is potentially upsetting (as well it should be) so to soften it the storyline takes the p.o.v. of the inanimate objects that surround the child and her family. It’s as if the very things she’s leaving behind want to help but can only wish for things to be different. Wishing is often the last refuge of the powerless, and no one has less power than a child. So while everything from the light to the sea wish that they could change the circumstances of what they are and what they’re doing to these people, only the girl’s wish actually comes true at the tale’s end.

A co-worker of mine asked me the wholly reasonable question of whether or not this book is a picture book or a work of informational writing. Which is to say, where do you shelve this in your library? Mượn Thị Văn is basing this story off of her own personal experience. From the family members to the destination of Hong Kong, this book is her own story. But the framework, I would argue, places it squarely in fictional territory. First, you have the aforementioned writing, which gives voice to the voiceless elements that control our lives. Then there is the sheer simplicity of it. It’s not an automatic problem. After all, the Jane Goodall picture book by Patrick McDonnell, Me… Jane is often cataloged as nonfiction as well. But unlike Me…Jane there are no specifics at work. All the context is in the Author’s Note, and few children will be reading that part. And so, what we have is a book that is based on the personal and embraces the universal in how it tells its tale.

If the text is simple, never using a single word more than it needs to, then consider how those words feel when paired with Victo Ngai’s intricacies. It’s enough to make you think seriously about the ramifications of picture books that combine easy texts with highly complicated artworks. What does that do for a brain, young or old, that’s reading it? It also makes me think about other books that have done similar pairings. Not wordless books, but books with very easy words that tell a story against a raucous riot of color and tone. When a book keeps the storytelling short and the art elaborate, your head uses the visuals to fill in the gaps. There is a method of reading aloud to children called the Whole Book Approach that was developed by Megan Dowd Lambert with books like Wishes in mind. In this Approach, the children examine the art closely from cover to cover. You consider every element, every choice made by the artist, every part of the book itself. And with a book like Wishes you can then relate how all of this informs its story of survival and escape, suffering and safety.

Repeatedly, Ngai’s art thrills. I don’t know how she makes her art, but it is epic visual storytelling at work. Not that I didn’t occasionally have questions. One element that did confuse me in the art concerns the final shot taken from the boat. As the family finally reaches a city, the image initially struck me as at odds with the rest of the book. It looked futuristic with its many pyramid-like spires and a bird-like statue in the harbor. Honestly, it reminded me more than a little of Shaun Tan’s The Arrival, when the immigrants on the boat come into the harbor for the first time. I expressed my discomfort with this image to a co-worker who was quick to reassure me that this was a shot of Hong Kong. Little wonder I wouldn’t recognize it. And true enough, it is difficult to find harbor images of 1980s, but looking at the picture it appears to me more like Shanghai than Hong Kong. My friend may be right, but I wonder if the artist thought to make the city the family is traveling towards more dream than reality. If this is a picture book then why tether yourself to what’s real when you can give your heroes hope in a whole new form?

One thing that I’ll take away from Wishes is how well this book will work with younger children. The increasing sophistication of children’s literature means that these days difficult subject matter will often make it into books for kids. In 2021 alone we’ve seen Unspeakable about the Tulsa Race Massacre and Hear My Voice about the children detained at the southern border. Those books require context and may be better suited to children capable of processing true tragedy. Wishes is a bit different in that it couches its horror in distance and beauty. By having the world around the family passively comment on their situation, right until the daughter speaks at the end, and the art sweep you along so that even the cruel, hot sun is this lustrous ball of flame and palpable beauty, you can read the book and understand the horror but also distance yourself enough that small children are still comforted. The kids in this book are hot and hungry and thirsty, but their mother, the trusted authority figure, is always there with them. She never leaves a single one of them behind. And that’s a comforting thing. It’s something to hold onto when the world itself is big and confusing and scary.

I can’t pretend to know how Wishes will be welcomed into the world. All I can do is hope that it finds its home. We have seen many picture books about immigrants and refugees over the last few years. Some are metaphors. Some are set in the past. Some are set today. They’ve been told with the immigrants portrayed as rocks and in others as animals. Some have been good. Some have been terrible. All have been interesting, and Wishes comes to us as one of the best. The personal story combined with the pitch perfect storytelling and jaw-dropping art means that this book is special. Its story may be set in the past, but its message cannot age or decay. Find a child, read it to them, and count yourselves lucky that both they and you have been allowed to experience this story together.

On shelves May 5th.

Source: Galley sent from publisher for review.

Videos:

Watch the author and illustrator talk about the book in a recent Scholastic preview:

Filed under: Best Books, Best Books of 2021, Reviews, Reviews 2021

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

2024 Books from Coretta Scott King Winners

Family Style: Memories of an American from Vietnam | Review

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

ADVERTISEMENT