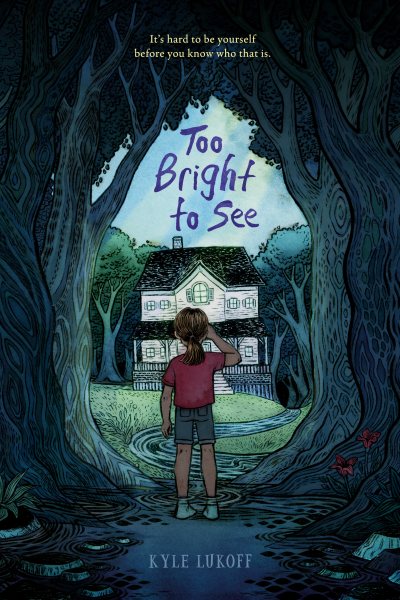

Review of the Day: Too Bright to See by Kyle Lukoff

Too Bright to See

By Kyle Lukoff

Dial Books for Young Readers (an imprint of Penguin Random House)

$16.99

ISBN: 9780593111154

For ages 9-12

On shelves April 20th

A great book can inspire a great review but it’s not a one-to-one correlation. Just because I’ve read an amazing book for kids, that doesn’t mean that I’m going to be able to string words together that make that fact tangible to anyone else. Many is the time that I’ve sat down to write a really ripping review only to find my fingertips failing over and over again to convey what it was about the book that was so very great. Authors, I have found, are still very kind when this happens. Your review might be a mighty font of mediocre and still they’ll tell you that it made them feel good. But other reviewers and members of the general public? They know. They know and you have to walk off realizing that you just completely failed to help place that book in the firmament of great children’s literature where it so richly deserves to be. Well not today, suckers! Today we are going to drill down and get right smack dab into the middle of why Kyle Lukoff’s Too Bright to See is as groundbreaking as it is. Because this isn’t just your average ghost story. When we talk about wanting to see a diverse range of books for kids, this is precisely what we should be thinking of. And yes, there will be oodles of spoilers. Best know that right now.

Uncle Roderick is dead to begin with. There is no doubt whatever, about that. Bug and Bug’s mom, who lived with him for many years, are distraught but getting by. Of course, for Bug, things are never actually normal. Their house is haunted (always has been) but that’s par for the course. What’s strange is that middle school is looming and Bug’s best friend Moira is determined to get them ready. That means makeovers, nail polish, shopping for clothes, the works! Bug’s not sure what to think about all this, even before the ghosts start acting increasingly strange. First there’s a broken bottle of nail polish. Then the destruction to a bedroom. As things escalate, Bug begins to suspect that this is the work of a brand new ghost. A familiar ghost. A ghost with a very specific message, but only if Bug’s ready to hear it.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Once I was on a plane flipping channels and I came across a ghost-related docu-series that appeared to have been strapped for cash in the course of filming. The television show was recounting a typical low-key haunting. Nothing like spooky noises or faces reflected in glass or anything like that. It was just that a woman had taken off her shoes by the front door, walked to the couch, and taken a nap. When she woke up the shoes were neatly tucked under the couch where she slept. Reader, I found this unspeakably terrifying. You can try to pull out all the usual horror techniques, but that simple act of something in your home not being quite right . . . that’s my nightmare. It is for that reason, then, that I highly enjoyed the scares Kyle puts in this book. There’s a kind of poltergeistish sequence that will probably get more attention from the kids, but for me the freakiest moment in the whole darn book is when Bug wakes up and sees everything in the bedroom has been thrown into chaos. Silently. While Bug slept. And now, if you’ll excuse me, I’m off to crawl under the covers of MY bed right now, never to return. I’ll spare you a description of the moment when Bug wakes up and opens a sock drawer.

Yet horror for horror’s sake rings hollow. You could get a ripping good yarn out of it, but horror is often most interesting when it gloms onto an aspect of society that someone, somewhere finds horrifying. The film Get Out is both a classic body snatcher storyline and a comment on race. Likewise, Too Bright to See takes little moments and makes them both scary and smart. The best of these is what Bug sees when looking in a mirror. Sometimes, we hear, the face in the mirror isn’t Bug’s. It does everything Bug does, perfectly, but it’s not BUG’s face. “It looks like someone’s idea of what I look like, without me behind it.” There are other examples of this, like the dream where Bug feels compelled to keep putting dresses on, even though they’re painful, and cannot seem to stop. Some kids will read, or even reread, this book and see what Lukoff’s doing with these moments. And when they do they’ll have this fantastic lightbulb moment. The kind of thing an author lives for.

There’s a moment at the end of the book where Kyle does something in his Author’s Note that I’ve never really seen before. He admits that if you tell other people precisely what this book is about you “might feel like taking away your friend’s chance to fully experience the story.” There’s an element of surprise about this book and Kyle addresses that. How does one discuss this book with other people, if you want to retain that element of surprise? He might as well be talking to reviewers too. You already read my warning up top that there would be spoilers in this review, so here’s the facts of the matter (which you may already know anyway): This is a trans narrative for kids, couched in language that could make sense to everybody. For example, at one point in the book Bug discovers information about transgender people under Uncle Roderick’s bed. “A lot of the trans people telling their stories talked more about a general feeling of not-rightness. Like people looking at you through a frosted glass window, guessing at what they were seeing.” And Bug, in the course of things, is discovering that he is trans. As this book becomes more and more famous (and it will) we’re going to have people approach it with assumptions of their own. And for them, reading this book will be about hearing about Bug’s journey. Bug, who doesn’t just feel like other people are looking at him through frosted glass. He’s seeing himself that way too, for quite some time.

What Lukoff does so well here is zero in on the changing self as self. This is perfectly stated when Bug critiques the “be yourself” advice that kids get. What “self” exactly? Books for kids do this all the time. “But those books never tell you how to figure out what your self is. They assume that you know already, and are pretending to be someone else for a while to fit in.” The book is so good at making Bug’s understanding of self as vague as it feels at that age. There’s a desperate honesty to it. Really, I kept thinking about how well Too Bright to See would pair with Pity Party by Kathleen Lane. Because that’s 2021 in a nutshell: The Year of Global/Bodily/Interior Uncertainty. Both books zero in beautifully on the dichotomy between what kids feel like and what they present. There’s a moment when Bug remembers being around a new kid named Griffin, trying to act “normal”. “Being around Griffin, just for a few minutes, felt like I was practicing how to be a better version of myself. It needs work, but maybe if I practice often enough it will start to feel natural. Maybe it will stop being something I have to practice, and something I’ll just be. Maybe that’s what growing up is like. Practice makes a person.” Don’t ask us, kid. There’s a whole slew of adults out there wondering that very same thing.

It doesn’t hurt any that the writing’s great. One such moment is when Bug is thinking about the different knots of kids in the cafeteria of the new middle school. “And I imagine myself floating past all of them, always on the outside, no one noticing me, because there’s nothing to notice. Like their groups form a complex molecule, a perfect organism, impenetrable and complete…” Or how about the time when Bug is wearing a dress borrowed from Moira: “It looks good, and makes my stomach hurt … More like I’ve swallowed my bike chain. Greasy and cold, rising up into the back of my throat, making me shudder.” Okay, I’ll stop myself now. But seriously, this is good stuff.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Kyle’s a former school librarian so you know he’s read a LOT of middle grade novels over the years. That can actually be a bit of a problem for a writer. I can’t speak for him, but I know that when I write I can sometimes have a hard time separating out different plotlines that I’ve already seen in books for children from the ones I myself want to write. The trick is to incorporate what you know. Take this book. At one point Bug has been given a surprise birthday party by Moira with a bunch of strange girls. It reads, “If this scene happened in a book, the older girls would be a little mean to me. Not outright bullying, but subtly making sure I know that I’m not one of them.” Oh god, it’s not just librarians like us that are tired of that trope. Kids are tired of it too. They are so familiar with the seemingly obligatory passive aggressive bullying scene that I can almost hear them all release a breath they didn’t know they were holding when Kyle wrote this. The girls who are hanging out with Bug? Nice people! Nice decent people. Did you know that they made nice decent people anymore? You wouldn’t if you read the bulk of MG novels out there. This book’s a breath of fresh air.

Now I’ll admit that it can be dangerous for an author to admit to the tropes of middle grade literature. Why? Well, why do you think they get used all the time? Easy drama. Take away that drama and what do you have? But the thing about this book is that there is plenty of drama. It just happens to be internal. And if the dang book ends with an understanding principal, nice kids, and a school that has five single-stall restrooms evenly spaced throughout the building, let it! You really can’t critique a book for giving its hero a supportive environment at the end. Anyone who says this ending is “unrealistic” will, in part, be saying that if a trans character doesn’t suffer at the hands of society then something is wrong. And that, my friends, is just stupid.

I’m an adult who reads books for children. Many, many books for children. Normally this isn’t a problem but on occasion I have to grab my own kids and use them to figure out if an author is doing something obvious or hidden. At one point in the book, Bug starts receiving messages from Uncle Roderick. The Ouija Board’s words give Bug a hard time, trying to figure them out. Looking at them, I thought it would be incredibly obvious to kids, but I wasn’t sure. So I grabbed the nearest 9-year-old and read the passage to her. To my infinite relief she was not seeing what I was. Not even slightly. It was both a relief and a reminder that when we critique books written for an audience to which we do not belong, we need to be careful about our assumptions.

Eleven years ago, trans author Jenny Boylan wrote the middle grade fantasy novel Falcon Quinn and the Black Mirror. And at the time we simply didn’t have any middle grade trans narratives, and that book seemed to be edging (slowly) in that direction. But compare that book then to this book now. Back then everything had to be couched in these metaphors so thick you could hardly see through them. Kyle Lukoff? His books are transparent. You see what he’s saying as he’s saying it, even if what he’s saying is couched in mystery at the story’s start. There’s not a wisp of obfuscation about the enterprise. Fans of ghost stories may find themselves disappointed that this book ends in self-discovery rather than a rip-roaring showdown with a furious phantom. They’ll get over it. The publisher sold this book to me as Doll Bones with a trans narrative and maybe that’s the best description you should hope for. Smart. Original. Necessary. Thank god we have this book now.

On shelves April 20th

Filed under: Best Books, Best Books of 2021, Reviews, Reviews 2021

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Top 10 Most Challenged Books of 2023

Double Booking | This Week’s Comics

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

ADVERTISEMENT