Review of the Day: Sugar in Milk by Thrity Umrigar, ill. Khoa Le

Sugar in Milk

By Thrity Umrigar

Illustrated by Khoa Le

Running Press Kids (an imprint of Perseus Books)

$17.99

ISBN: 978-0-7624-9519-1

Ages 4-7

On shelves now

It’s an old saying that states that if you told a childless person everything parenthood entails they’d never sign up in the first place. I’m not talking about the big things like guiding them on a true moral and/or spiritual path. I’m not even talking about the little things like changing diapers. I’m talking about the esoteric, nebulous, gray area things. The ideas and concepts and problems that are so vast and complicated that simplifying them for children can feel kind of like cheating. Take the issue of immigration. Some people simplify the issue to say that the United States is full up and can’t take any more immigrants. That we simply do not have enough resources. Other people simplify and say that there is plenty to go around if we’re willing to work together, share, and change. Happily, if I were to walk into a children’s library and ask for picture books about immigration I would find plenty of books that incline towards the latter attitude rather than the former. But let’s say a child wants to know why some people don’t like immigrants. Some picture books will try to explain this with metaphors about evil kings or military rule. Others take a subtler approach. Kings? Sure, the book Sugar in Milk has a king but he’s not the center of the story. He’s not even the most interesting element. And while this book doesn’t dive deep into why he reject immigrants initially, it does show in the simplest possible manner how such attitudes may change when confronted with ingenuity.

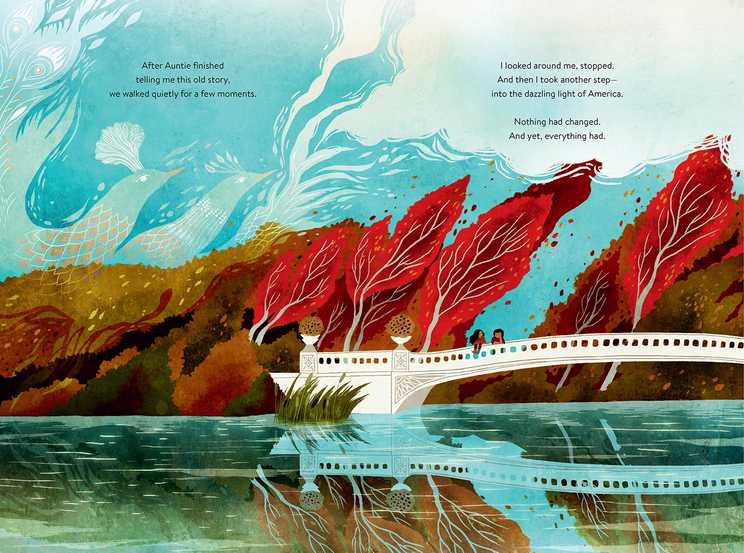

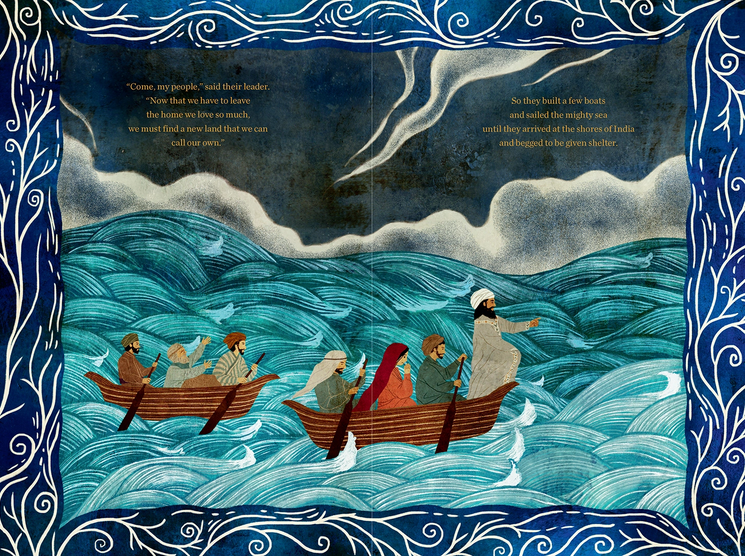

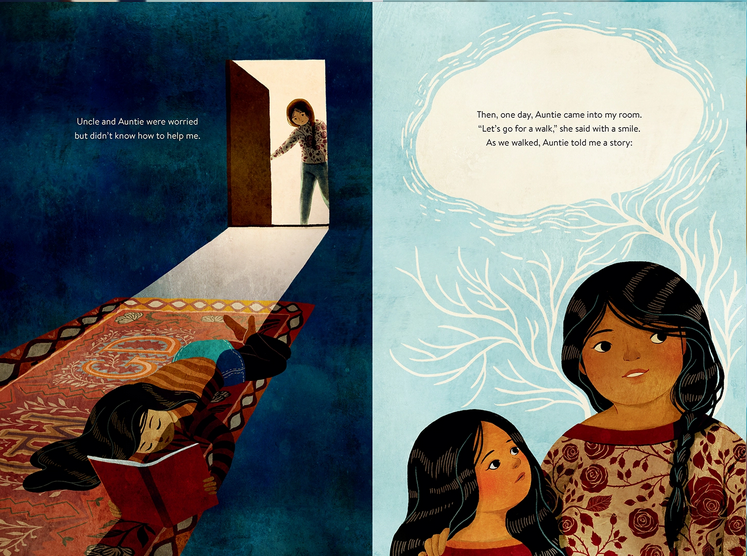

A girl is living in America but she is not happy. Though Auntie and Uncle shower her in gifts and books and beautifully colored walls, she misses her family and her cats. Sure she wants to make friends, but how? One day, Auntie takes her for a walk and tells her the story of a group of immigrants from Persia that was forced to leave home. After sailing for a long time they ended up on the shores of India. Unfortunately, the leader of India was not inclined to take in a people that looked different and couldn’t speak the language. After meeting them on the shore, the king found that the best way to convey his attitude without words was to fill a glass all the way to the very top with milk. You see? All full up. No room. Fortunately, the leader of the travelers was a clever man. Taking a spoonful of sugar from his bag, he stirred it into the milk, then handed it to the king. Getting the message, the king was rather charmed by the gesture and agreed to let them stay. Hearing this story, the girl thinks on the story, and slowly comes to appreciate this land she has come to. A land where there are friends to make and days to enjoy.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

The Parsi story about placing sugar in milk to convince a leader that there is a benefit to new cultures/people is not original to Ms. Umrigar. Indeed, the legend was told to her as a child growing up in India and she carried it with her when she moved to the United States. As a librarian ever on the lookout for folktales of any sort, I’d never encountered this story before and was moved by the succinctness of the tale. It doesn’t hurt matters any that Umrigar tells it without a word out of place. It gets the point of the story across to the reader without pounding it unnecessarily into their heads. Consider the unspoken message that the leader of the Zoroastrians conveys to the king. “If you let us stay, O Mighty King, we will live in peace, beside all of you. And just like sugar in milk, we will sweeten your lives with our presence.” If you’ve ever tried to write a picture book then you know how difficult it can be to convey an idea with a minimal number of words, but with all the emotions of a novel. Umrigar’s book consistently manages to give you heart palpitations with the shortest possible sentences. You are reading an artist at work when you read this book.

And speaking of what an author doesn’t say, let’s look at the framing sequence of this book a little closer. Umrigar doesn’t bother with explanations in general. Our unnamed heroine is a child immigrant. She’s come to a large city (NYC, perhaps) alone and the first sentence (accompanied by a shot of her walking with a suitcase in the snow) is, “When I first came to this country, I felt so alone.” We are not going to learn why she is here. We are not going to know why she left. We are not even going to know whom these people are that she’s staying with. She calls them Auntie and Uncle, but that could be a term of respect if nothing else. They clearly care about her, but as the book says, “my friends and my family were all back home.” Whatever she has left, she didn’t necessarily go because she was bereft. Now child readers don’t need everything spelled out for them. Generally speaking, the human brain takes pleasure in filling in gaps on its own. There are few things I love more than reading to a kid and seeing that little light bulb turn on in their noggins when they realize what’s going on in a book. The trouble here is that they’re never going to get any additional information. There’s no backmatter to spell out the situation. No note in the summary on the back of the book. You’re on your own with this one, kids! For most children, ain’t no big deal. For a few? A deal breaker from page one onward.

It was not until I was typing the name “Khoa Le” idly into my blog’s search engine that I came to the rather latent realization that I already knew her work. 2020 is turning out to be a bit of a banner year for Le. While Sugar in Milk is depicting a Parsi-American immigrant story, over at Carolrhoda Books, Khoa Le has also illustrated the Hmong-American immigrant picture book The Most Beautiful Thing by Kao Kalia Yang. Once I realized this I was actually a bit puzzled. On the surface the fact that Le has done both books seems obvious. Both titles are sumptuously drawn, one flitting back in time to a grandmother’s past and the other to ancient India. But when I placed the books side-by-side, I felt an overwhelming admiration for their differences. For all that the color schemes are similar, there is a delicacy to Sugar in Milk that varies wildly from The Most Beautiful Thing. Here, Le is playing with light, as when Auntie opens the door to see the girl stretched out on the floor of her dark room. She’s still filling every page with an overwhelming amount of detail (Auntie’s rose shirt alone is worth a paragraph, but I’ll restrain myself), but the entire feel of the book is different. I can’t describe it any better than that.

In the case of Sugar in Milk, Le is being asked to put a story within a story. It’s a common narrative technique but it poses a challenge for an artist. To confuse young readers as little as possible, it’s a good idea to do something that distinguishes the tale from the world of the person telling it. In the case of this story I found myself looking at what Le does with borders. It reminded me of the Evan Turk book The Storyteller in that way. Ultimately, the borders reflect the mood of the characters. When the King rejects the immigrants out of hand, the borders grow simple and dark. The vines that once curled around the story’s edges have faded and the outlines of leaves are there but there is nothing bright about them. Then, as the Zoroastrian leader conveys his message with sugar, they uncurl. They flourish. They blossom with new intricate vines, studded with leaves and plants and by the end they’ve deepened and burst into colors of their own. The first time you read the book, the borders do not catch your attention. However, you unconsciously understand on some level that this story is different from the one you were previously reading.

Why does a child want a book to be reread? Generally speaking it’s because there’s something in that book that appeals to them on their own level. Now over the last decade or so I’ve read a lot of picture books featuring immigrant children and their families. Some of those books were offensive or poorly written while others were dull or just sort of blended into the sheer number of picture books released each and every year. A couple stand out, mostly because they manage that impossible task of combining child friendliness (a kid will want to reread it) with good writing (an ADULT will want to reread it – never a given), and beautiful art. It’s the glorious trifecta of children’s book publishing and together Thrity Umrigar and Khoa Le have managed it with Sugar in Milk. Part fable, part realistic fiction, this is the kind of book that conveys its message effortlessly. It’s like they say – a spoonful of sugar helps the milk go down.

On shelves now.

Source: Final copy checked out from library for review.

Filed under: Best Books, Best Books of 2020, Reviews, Reviews 2020

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

One Star Review, Guess Who? (#211)

Kevin McCloskey on ‘Lefty’ | Review and Drawn Response

Notable NON-Newbery Winners: Waiting for Gold?

The Seven Bills That Will Safeguard the Future of School Librarianship

Take Five: Newbery Picks, Part Two

Gayle Forman Visits The Yarn!

ADVERTISEMENT

I’m such a fan of Khoa Le’s art and can’t wait to see this book for myself! A question: given that the story is about immigration, do you think Le intentionally chose to use borders for the story within a story to make a connections with the concept of international boarders and who can pass through them and who cannot?

*a connection

Well that’s a much more intelligent reading of it than I was presenting. I can’t think it’s a coincidence. Well spotted!