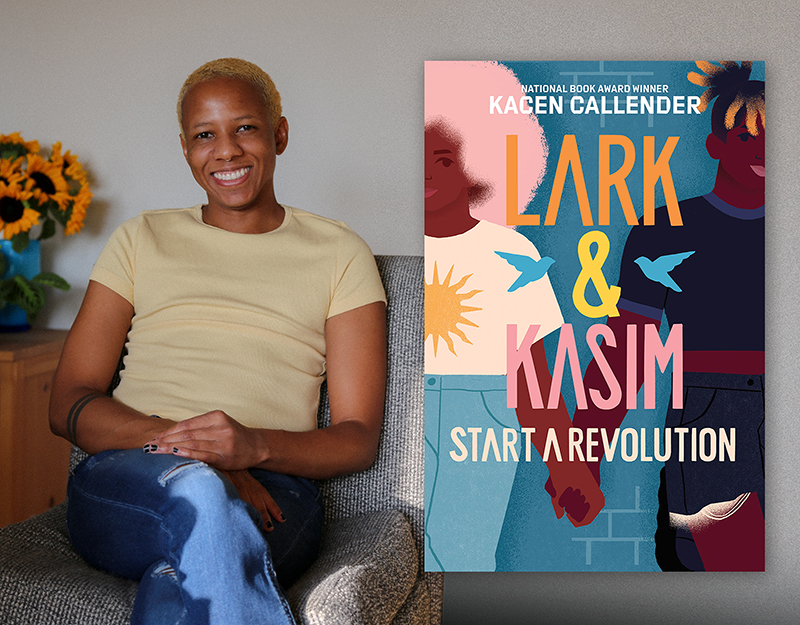

Review of the Day: Drawing on Walls by Matthew Burgess, ill. Josh Cochran

Drawing On Walls: A Story of Keith Haring

By Matthew Burgess

Illustrated by Josh Cochran

Enchanted Lion Books

$18.95

ISBN: 978-1-59270-267-1

Ages 6-10

On shelves now

There lives, within me, a horrible child. A real little monster. A useful little monster, actually, since it guides my reads on children’s books. Except that this interior devil child has a real thing with picture biographies. Put simply, it doesn’t care for them. Now I, mature 42-year-old librarian me, love picture book biographies and appreciate them in large part because they were fairly rote back when I was a kid. Unfortunately, the monster child that resides in my gray matter loathes most of them. For example, the other day I was reading a lovely picture book bio of Mr. Rogers and the child kept asking why it should care. A nice guy had a TV show but so what? What about the book would appeal to a 8-year-old today? I have a hard time answering some of these questions, so I pay extra close attention when a picture book bio soothes these concerns with every turn of the page. Like other bios of artists written for children, Burgess and Cochran’s consideration of Keith Haring could easily have explained with hoity-toity words why all good little children should know the man’s work. Instead they tell you the facts, and in doing so show you why the man deserves to be remembered. Never taking its eye off of what matters (that kids should find picture book bios interesting and not just something their parent/guardian/teacher/librarian makes them listen to) Drawing On Walls justifies its very existence by justifying the very existence of its subject. And my inner child critic is appeased.

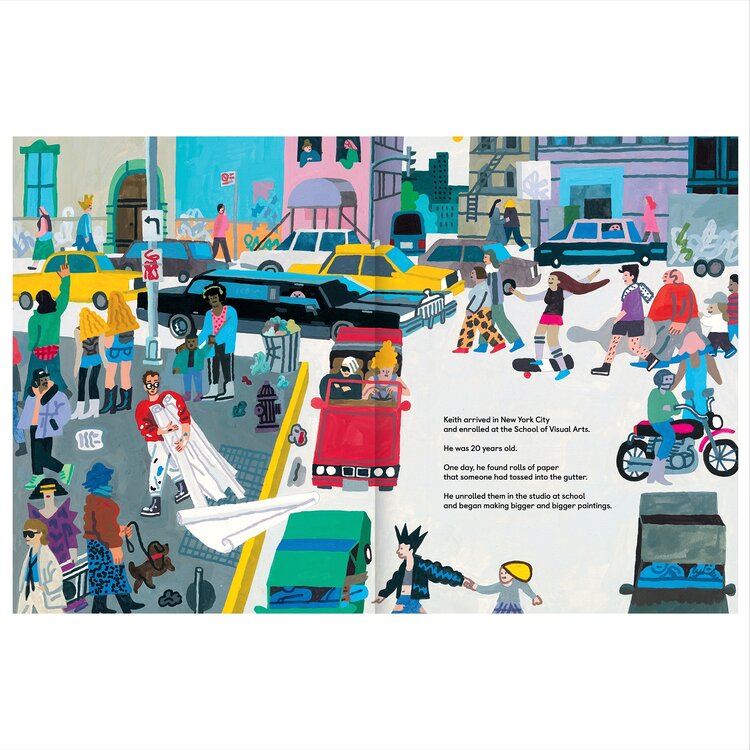

When Keith Haring was a kid he’d draw with his dad, do art with his sisters, and eventually create a studio in a friend’s garage. Art was always a part of Keith, but he needed to find his own style. Art school was a bust (commercial art just didn’t suit him) so off he went to NYC. There, Keith worked odd jobs until he was offered his own one-man show in Soho. Yet through it all, he mentored and taught and worked with kids and their creativity. For example, with high school students he created a 488-foot mural. And when he was diagnosed with AIDS? Well, he kept working as long as he could. A biographical note, notes from the author and illustrator, and list of sources is included in the back of the book.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

It must be kind of fun to write a picture book biography. Imagine all the different ways there are to tackle the subject matter. You could take a representative moment out of the subject’s life, or, better yet, childhood, and use it to explain why they were so important to the world. You could try to sum them up from childhood to adulthood. You could show them as adults, double back to childhood, then rush to their most important historical moments. The possibilities abound! In Burgess’s case, he gives you a brief glimpse of adult Keith at the start then pulls back into his childhood. Parts of the story are almost suspiciously perfect, like when you learn that Keith’s siblings were Kay, Karen, and Kristen (and they lived in Kutztown). It seems like a pretty standard way to begin, but take a look at what the author’s doing here. With Keith’s early life you see him showing his younger siblings how to make art, an act mirrored in Keith’s later life. Then, perpetually, throughout the book, Burgess takes time to bring the book back to Keith’s connection to kids. The best part of this isn’t merely the fact that it gives the book a strong theme, but also that it entices the child reader to be a part of the story. Kids reading this book are reading about a real artist, a great artist, who involved children in his public art. Keith acted like a child sometimes himself, like when he drew on the black subway panels with white chalk. But ultimately, this dedication to a through line or overarching theme also makes the book something a kid would not only want to read but also return to. Oh. And the book is poofy. You can squeeze the covers and they have a little bounce. I feel like it’s important for me to mention that fact.

In his Author’s Note, Matthew Burgess mentions that when he was shopping this book around, some publishers weren’t entirely on board with his approach. “I met some skeptical responses as I began to share the idea, primarily around Keith’s homosexuality and illness. Fortunately, my publisher Claudia Bedrick, and I saw eye-to-eye about the need for greater openness in children’s books.” I read this and felt a little stunned. I mean, it’s 2020 and book publishing is always coming out with titles with LGBTQIA+ content, right? Yeah, but then I thought about it and realized something. There’s a moment in this book when Keith is riding the subway with his partner. The text reads, “A few years later, when Keith was 23, he fell in love with a deejay named Juan DuBose.” The accompanying picture shows the two men cuddling together on the subway seat. Juan’s arms are around Keith and Keith’s head is resting on Juan’s shoulder. And I stared at that image, shocked to realize that I have almost never ever seen an image with that level of tenderness between two gay people in a picture book, nonfiction or fiction, in my life. We have strong bios of gay rights activists, yes! We have books on Stonewall and collected biographies of activists. We have stories of folks like Harvey Milk and Gertrude Stein and all that stuff, absolutely. But do we ever see a single cuddle? A snuggle? A small private moment that shows that two people really and truly do care about one another? It says something about our publishing industry when love of this sort is this rare.

Picture book biographies of artists face difficulties that pic bk bios of, say, marine biologists do not. To completely imitate the style of the artist feel hackneyed. Like a low-rent version of the very person you’re attempting to celebrate. That said, nothing makes my blood boil more than a book that lauds the artistic achievements of someone without ever showing the reader the art, or at the very least the style, that made them great. What you need is a kind of odd compromise between these two extremes. Ideally, you need someone who can invoke a general feel of the original artist without looking as though they are imitating them. To choose Josh Cochran for this particular project was nothing short of inspired. The man has created a whole swath of different murals over the years, a talent he shares with Haring. As for his style, it manages to invoke Haring without replicating him. Thick black lines and busyness don’t scare him off. Heck, he relishes them! Page through this book and you see this amazing balance between the subject and the subject’s passion. In his “Illustrator’s Note”, Cochran says that when he was a student at the Art Center College of Design there was a Haring mural across the hall from the library that he’d admire. “Every time I stopped to admire the piece, I would have the same two thoughts: this is the most incredible thing I’ve ever seen, and how did he make it?” It seems to me that an artist that appreciates the mastery of Haring is the ONLY kind of artist you can have illustrating this bio.

As I read through this book a couple times, I really came to admire what Cochran is able to pull off here. First and foremost, he zeroes in on a very clever way to draw your eye to Keith on every page. When Keith is present, his glasses are always prominent, and the white lenses pop out at you. For all that the pages are busy, as when he goes to NYC for the first time, Cochran has managed to avoid the inevitable Where’s Waldo-esque search that could come from trying to locate Keith on each and every spread. Now take a look at how the book is laid out. The endpapers are a mishmash of pink lines on a maroon background. Kinda Basquiat-ish, if I’m going to be honest. Turn the page and you find a pure white page of dedications facing a pure orange page of quotes. Turn the page again and now we’re on the title page and at the top is a line of children, walking to a destination. Where? Turn the page and now you, dear reader, are the canvass. Or maybe, to be more precise, you’re a wall. Keith is painting thick black lines on you while, behind him, those children we saw before are holding paintbrushes, prepping to fill in his work. So Cochran has both literally and metaphorically put you into the center of the story right from the start! And while the colors pop and the lines are big and black and thick, it’s almost as much fun to watch the design at work (scribbles spilling over a book’s gutter to start to fill the other side) as the art itself.

Any time we decide to pluck out a human from the morass of humanity and declare, “This person is worthy of celebration” we are making an enormous judgment call. No human being is perfect, but when you write history for children you find yourself wanting to avoid the complicated messiness of being human in favor of the easy simplicity of mindless praise. A good picture book biography, aside from finding a subject worthy of children’s admiration, finds a balance between myth and reality. It constructs narratives from the messiness of life. While you live, there’s no set path before you. But when you write about someone famous (or someone who deserves to be famous) you have to make it seem like their life had form and structure. To do that without being boring yet full of amazing artistic and design decisions, to say nothing of an appreciation for the reality of living, is no easy matter. Drawing On Walls is the kind of book that you wish other writers of children’s nonfiction would read. Because, honestly, if the little cynical child in my head can get into the groove of the story here, maybe we need to see more books like this in the future. Many many more.

On shelves now.

Source: Final copy sent from publisher for review.

Filed under: Best Books, Best Books of 2020, Reviews, Reviews 2020

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Name That LEGO Book Cover! (#53)

K is in Trouble | Review

Fighting Public School Book Bans with the Civil Rights Act

Take Five: Middle Grade Anthologies and Short Story Collections

ADVERTISEMENT