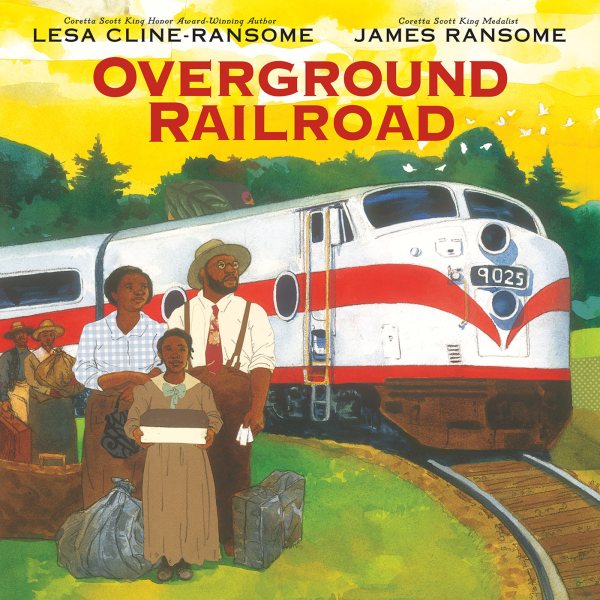

Review of the Day: Overground Railroad by Lesa Cline-Ransome and James Ransome

Overground Railroad

By Lesa Cline-Ransome

Illustrated by James Ransome

Holiday House

$18.99

ISBN: 978-0-8234-3873-0

Ages 4-7

On shelves now

The standard joke amongst children’s librarians is that we learn most of our American history through children’s books. But of course the unspoken suggestion there is that this is history we never learned in school. Now I don’t care how amazing your education was in the 1980s. Pretty much I can guarantee that unless you were part of the slightest sliver of students, odds are back in the day you had never heard of the Overground Railroad or The Great Migration. Heck, I only got the most superfluous smattering of information about the Underground Railroad, and most of that was due to Virginia Hamilton’s The House of Dies Drear, but I digress. Now that I have children of my own to whom I can read books like Overground Railroad by Lesa Cline-Ransome and James Ransome, it is taking all my restraint not to punctuate every other page of this book with little asides like, “Do you kids know how lucky you are to even have books like this right now?” and “Are you fully appreciating how much better your sense of history is going to be than mine ever was?” I am good. I don’t do that. I don’t do it even though I am simultaneously seething with jealousy over all the opportunities for a fuller education they’re getting while, at the same time, feeling so pleased that books like this one are being published. No series of rote facts, Overground Railroad puts you in the shoes of the ordinary people that had to leave everything and everyone they knew in search of a better life. Historical events like The Great Migration are vague. This book hands young readers not just specifics. It hands them people they can get to know and care about.

It’s early in the morning when they leave. Ruth Ellen, Mama, and Daddy. “We left in secret before Daddy’s boss knew.” Just the three of them with just a couple of bags, leaving everyone and everything they’ve ever known. Joining throngs of other people on the trains, going North. On the train they get some seats for a journey that’s going to be long. In the South they have to sit up front. In the North they move to seats farther back in the train. All the while they eat the food packed for them, listen to Ruth Ellen read from her book Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, and dream of the future. Dream until they arrive in New York City, “bright lights tall buildings shimmering against a sky bright as a hundred North Stars.”

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Something happened to Lesa Cline-Ransome and James Ransome. These guys have been making children’s books for years and years and years. They’re not newbies by any stretch of the imagination. Twenty years ago they were doing a picture book biography of Satchel Paige and they haven’t stopped since. But at some point in the last three years their collective career just took off like a shot. For my part, I’d always liked their books but Before She Was Harriet was the game changer. With that book, Cline-Ransome tipped the whole notion of a biography on its head. She told Harriet Tubman’s story all right, but she told it backwards in the context of each job that hero had ever held. It was unique, interesting, riveting, and deserving of more awards than it received. Overground Railroad doesn’t muck with timelines the same way Harriet did, but there’s something mesmerizing in the way it uses each stop on the train line as a method of marking the journey. Even if a kid doesn’t know the difference between Rocky Mount and Washington D.C., they pick up on the pertinent details. It also allows for all kinds of different discussions With this book I was able to explain to my kids the difference between making black people sit at the back of a bus verses making them sit at the front of a train and why, in both cases, it was awful.

I took my time examining precisely how James Ransome put together this art, and the stylistic choices he made to support the narrative. According to the publication page this book consists of paper, graphite, paste pencils, and watercolors all working together. Of course, the very first thing about this book that you see, aside from its cover, are the front endpapers. Split into four quadrants, Ransome shows the different methods black people had to take to go North, including walking, the bus, the train, and by car. You might miss on an initial glance the fact that overshadowing all these scenes, laid over them, is a cotton plant. It sticks out, touching every possible aspect of these four pictures, giving the impression that what these people are escaping is how that cotton has wormed its way into every aspect of their lives. The cotton is rendered very simply. It is present, but it is easy to miss if you’re not looking for it. There’s even a cotton plant featured on the book’s dedication page before the story starts and a field of them in the foreground of the page featuring the Author’s Note and a train escaping out of sight. For the rest of the book, Ransome keeps his images realistic. I loved the peachy pink of the early morning skies and when the artist chose to make something a bold block of color, patterned fabrics, or fine details. There is also a shot of Ruth Ellen and her family walking through a dining car past white people that I can’t stop staring at. The white people are made of a different shade of paper, often crudely cut out. They almost all stare, and there is a side-eye Ruth Ellen’s mama gives them that makes it clear that she is perfectly aware of the situation and is monitoring it.

By complete coincidence this is not the only book out in 2020 with this title. Coming out at pretty much the exact same time is the adult work of history Overground Railroad: The Green Book and the Roots of Black Travel in America by Candacy Taylor. All of this dovetails with what I’m seeing my own kids learn in elementary school these days. The Great Migration has gone from footnote in a child’s history book (if you’re lucky) to its own expanded unit. And children’s literature has done what it could to provide additional books and resources on this topic. Overground Railroad pairs beautifully with Jacqueline Woodson’s, This Is the Rope or Eloise Greenfield’s, The Great Migration. One detail I would have loved Ms. Cline-Ransome to include, though, is dates. The Author’s Note at the end spells out clearly how the owners that operated tenant farms exploited the sharecropping system. What it does not say is when in history The Great Migration took place. If I’m a kid and I see this book then I could be forgiven for believing it takes place right after the Civil War, and we know this is not the case. It didn’t have to be an extensive timeline or anything, but just a quiet mention of dates could save a bit of confusion on the part of the child readers (and, let’s face it, plenty of adults as well). As it stands, the sole indication is a newspaper someone reads during the story that declares the date to be May 15, 1939.

You don’t have to look very far to find contemporary stories of people fleeing oppression, heading North to look for a better life. The dates have changed but the reasons remain the same. The creators of this book draw no direct line between migrant stories and Great Migration tales, but there is one little sentence at the end of the Author’s Note that gives the reader a chance to think. She writes, “Overground Railroad is inspired by just one of the many stories of people who were running from and running to at the same time…” We teach our children history so that they can understand current events better. So that they will develop a sense of empathy and compassion and understanding for the ones who came before. So many of these stories have been lost to us, so I find great comfort in the storytellers that imbue them with new life. If you don’t read Overground Railroad you’ll continue your merry way, not knowing what you’ve missed. But of course, if you’ve read this far into the review, you do know. Now you can’t claim ignorance. And, all things being equal, neither will any of the children that are fortunate enough to get a chance to read this book. Unavoidable, necessary history.

On shelves now.

Source: Final copy sent from publisher for review.

Filed under: Best Books, Best Books of 2020, Reviews, Reviews 2020

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Happy Poem in Your Pocket Day!

More Geronimo Stilton Graphic Novels Coming from Papercutz | News

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

Environmental Mystery for Middle Grade Readers, a guest post by Rae Chalmers

ADVERTISEMENT