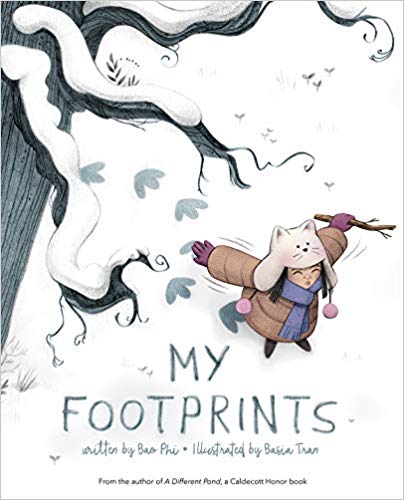

Review of the Day: My Footprints by Bao Phi, ill. Basia Tran

My Footprints

By Bao Phi

Illustrated by Basia Tran

Capstone Editions (a Capstone imprint)

ISBN: 978-1-68446-000-7

$19.99

Ages 4-8

On shelves now

Have you ever worked backwards from a picture book in an attempt to figure out how the author came up with the final product? No one can ever truly know a writer’s process except the writer themself, but as an exercise in revision it can be fun to try. For the best results, I suggest starting with a picture book that doesn’t slip into the crowd unnoticed. For example, in a given year I can read so many picture books that they all start to blur together. But when I read My Footprints by Bao Phi, the final product was so original and unusual that I couldn’t help but remember it months and months later. I returned to it, and just this evening I reread it to see what it was that stayed so clearly in my mind. For kicks, I tried figuring out how the author was able to reach the final product in the way that he had. Reader, I failed magnificently because no one, save Bao Phi himself, knows how this book was truly constructed. Fortunately, you don’t need to know. All you need to do is locate it, read it, and discover a story about family and frustration (not necessarily in that order) and fantasy. Welcome to a book that recognizes that every family is its own chimera.

Walking home in the snow from school, Thuy’s hurt. Kids at school are laughing at her again. Maybe it was because she has two moms, or she’s a girl, or because they’ve told her to “go back where you come from,” but whatever it is she faces it by turning her footprints into the prints of different animals. Small prints first, like birds or deer. Then bigger prints like leopards and bears. Finally enormous prints. And with the help of her Momma Arti and Momma Ngoc, the three are able to become magnificent, huge, magical creatures. Powerful and kind. Or, as Thuy puts it, “An unexpected combination of beautiful things.”

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

I couldn’t work out how Bao Phi wrote this book without first determining why it strikes me as so different from other picture books on the market today. So to start, let’s examine the opening of the book. People talk a lot about first sentences as they apply to novels, but picture books benefit as highly from a well placed turn of phrase. The first sentence of My Footprints reads, “Thuy sees those kids laughing at her again.” The reader has been dropped into the story not just at a moment in progress, but at a dramatic and emotional moment that will set off the whole book. Bao could have gone a far more standard route. Maybe begin the proceedings with something dull like, “One day Thuy was leaving school when she ran into two classmates she didn’t like very much.” My husband is a screenwriter and he has a phrase I’ve appropriated for picture book writing. Whenever you have something superfluous in your text, “it comes right out.” Anything preceding the actual first line of My Footprints comes right out. We don’t need to be eased into this. That first sentence grabs the reader’s attention immediately. It doesn’t ask for your permission to begin. It dives right in.

Part of the advantage of a book that leaps into the storytelling is that if you’ve been thrown just a little bit off at the start, you’re almost more willing to accept similar surprises in the text as you read. That first sentence is followed soon thereafter by, “The white crisp blanket of new snow cracks like eggshells beneath her feet.” So the author has plunged you into an emotional situation, then followed it up with delicious, familiar (to some) descriptions. It’s here that Thuy notices her footprints in that snow and starts turning them into different animals as she walks home. That’s a fun thing kids do anyway, but each one, you come to realize, has a connection to her anger and frustration. Bao also takes care to imbue the book with those conflicting emotions that take hold of us sometimes. There’s a moment when Thuy asks if snakes have butts and her moms laugh. “Thuy laughs at first too, then frowns. She feels like a sudden snowstorm.” I can already hear child readers become confused by her shifting emotions. The author opens the book up in this way, inviting kids and the adults reading to them the chance to talk about why Thuy might be acting the way that she is. Bao uses unexpected dips and snags in the text to give you the same sense of the roller coaster emotions that his heroine is feeling. It’s a textual risk, and it pays off.

And none of this is even talking about the central metaphor of the book. I like to talk a lot about books for kids that have messages. I’m not anti-message. I’m anti-poorly done messages. The least interesting children’s authors spell things out in great big blocks, because they are under the distinct impression that it is the more efficient method of teaching children. I can’t argue the efficiency, but lord can it be awful to have to read. A poorly written message is a clunky creature. It makes you all the more appreciative of authors like Bao Phi. In this book he’s telling a story about a girl who is urged by bullies to feel shame about her looks, gender, and family. To build herself up on the way home she embodies different animals. Then, when she is with her moms, they encourage her to join them as they become mythic creatures that are the embodiment of different animals joined together. The author gets close to giving away the game altogether when Thuy makes up her own magical creature, but somehow he manages to pull her back from the brink of obviousness. The metaphor is there for the kids to grasp and understand if they want to, but if they don’t then you get to see cool creatures like the phoenix and the sarabha, and that’s pretty darn neat in and of itself.

Artist Basia Tran is relatively new to the picture book scene. Using graphite and digital color, her style is intriguing. She makes choices that I like, while there are others I might change. For example, I was quite taken with the ways in which she plays with perspective. In one picture we look down on a cardinal in a tree who, in turn, is looking down on Thuy. I loved the meticulousness of the feathers on his back. I like too how the artist will sometimes break the text into long panels, or close-ups of Thuy’s face, and occasionally from below looking up. Of course, there are some things I might change with some small revisions. The first time we see Thuy’s moms, one has a shovel and is standing in the middle of the path to the house (makes sense) while the other one is standing with her own shovel like a statue, unaccountably in the middle of the yard. In Thuy you get this clear cut sense of personality and spark and sparkle. The moms, meanwhile, will carry the same expressions at the same time. They’re a unit, rather than individuals, and I get the reasoning behind rendering them that way, but it would have been nice if they’d been allowed a little more personality than we’re seeing here. It’s fortunate that Basia is so adept at giving the mystical its honest due.

In his Author’s Note at the end, Bao Phi writes that, “One thing that may be universal to all parents is, we want our kids to have an easier, better life than we did.” Having difficult conversations with your children, and not dismissing their problems, is one of the hardest parts of being a parent. It’s funny, but at first I thought that the parents in this book were avoiding that kind of a conversation with Thuy. It was only after I read it over a couple times that I realized how perfectly they were giving their daughter an opportunity to open up to them. Indeed, after she closes up, her imaginings allow her to say all kinds of things to them about her problems that she might never confess otherwise. I wouldn’t label this as a set of guidelines for parents, but it certainly models good behavior for adult readers. Add on the fact that it has realistic situations, an imagination used for the ultimate good, magical creatures, tip top writing, and plummy art and you have yourself a story like few others out there today. Want a book that’ll stick in your brain for long periods of time for all the right reasons? Chant along with me then . . . my footprints, my footprints, my footprints . . .

On shelves now.

Source: Galley sent from publisher for review.

Videos:

Filed under: Best Books, Best Books of 2019, Reviews, Reviews 2019

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

One Star Review, Guess Who? (#206)

UnOrdinary | Review

Navigating the High School and Academic Library Policy Landscape Around Dual Enrollment Students

Take Five: New Middle Grade Books in July

ADVERTISEMENT