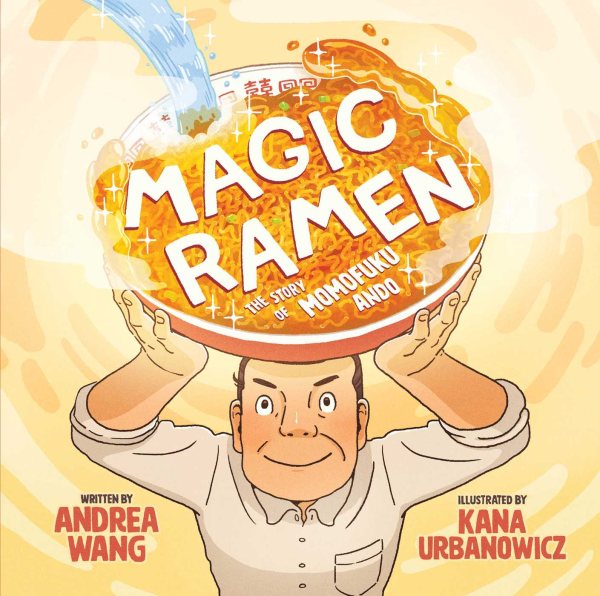

Review of the Day: Magic Ramen by Andrea Wang, ill. Kana Urbanowicz

- Magic Ramen: The Story of Momofuku Ando

- By Andrea Wang

- Illustrated by Kana Urbanowicz

- Little Bee Books (an imprint of Bonnier Publishing USA)

- $17.99

- ISBN: 978-1-4998-0703-5

- Ages 4-7

- On shelves now.

Sometimes, to train a child to be a reader with wide tastes and a full body of knowledge, it is imperative to train their parents at the same time. New parents today are often unaware of the sheer scope of topics they can read to their children. I sympathize. When we were kids you had your picture books, maybe your comic books (but almost never from the library) and then came the older stuff when you were able to read on your own. For nonfiction or informational books I can only clearly remember the “Childhood of Famous Americans” series, which probably wouldn’t pass muster as “nonfiction” in this day and age. Factual picture books existed but they were hardly numerous. These days, it’s an all-new ballgame. Never before have so many fun and interesting topics appeared on such a great grand scale. It is the wise parent that not only pairs their child’s interests to topics they already love (example: You like super soakers? Then read Whoosh! by Chris Barton about its inventor!) but seeks out fun informational picture books on topics never before tackled in the juvenile reader realm. One such book landed just this year and it is so successful a venture that at least six librarians of my acquaintance have raved about it to me. Magic Ramen: The Story of Momofuku Ando looks like a simple tale about the man who invented instant ramen, but look closer and you’ll see that what the book truly is is a paean to the necessity of failure, the beauty of persistence, and the pleasure that comes after messing up 99 times only to get it right on the 100th.

1946. World War II ended more than a year ago but Japan is still recuperating. One day Momofuku Ando walks along and sees a line of starving people waiting for horrendously overpriced ramen. The image burns itself into his brain and ten years later he still can’t keep from thinking about that line. What if it were possible to make ramen that was cheap and nutritious and delicious and fast? With those thoughts in mind Ando tries and fails to make the right noodles. Even as one solution appears, another problem rears its ugly head. Next he tries to figure out how to turn the broth into soup. When that’s solved he has to figure out how to make it instant. Though failure is constant, Ando finally comes up with the solution and as a result ramen noodles are a staple worldwide, helping hungry people, poor people, and busy people everywhere.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Now when I heard that this book was about the invention of ramen, I honestly thought that all ramen in the world was the instant kind. I’ve never been to Japan and my connection to ramen came solely through my college experiences with that big block o’ noodles you drop into a pot. Imagine my shock, then, when I see ramen mentioned on the third and fourth pages of this story. What can that mean? How can you invent something that already exists? I didn’t understand. What I also didn’t understand (aside from the rudimentary differences between instant ramen and the kind you make painstakingly by hand) is that this book isn’t just a food book and isn’t just a picture book biography. It is a food-related INVENTOR book! For years, children in schools have been told to do reports on inventors. This is not, in and of itself, a problem except that in the past the majority of books about such people were filled with white guys. These days you have so many more options. After all, inventing food is something kids can completely understand.

As with any picture book biography, you have to determine how best to frame your subject. Since the focus of this book is Momofuku Ando’s discovery, where do you start? Do you find some significant fact about his childhood and start way back then? Do you try to show every minute of his life from birth to death and onward? Or do you let the discovery itself lead the story by the nose? Wang opts for the latter option and the book is better for it. We don’t actually need to know much of anything about instant ramen’s creator above and beyond his empathy for the hungry and his desire to make a difference. Bog it down with further ideas and you get a soggy story. Not appealing.

Of course, the truly great informational picture books can not only adhere to the truth of their subject matter, but also say something to child readers that, hopefully, they’ll understand on some level. In the case of Magic Ramen the message is about messing up. Failure is absolutely necessary when inventing something new. So it is that we see Ando attempt to solve his problem from all kinds of different angles. We see how he gets ideas for new solutions, and how even as he figures those out, new problems raise their ugly heads, making even more solutions necessary. And does the man fail? He does. Over and over and over again. The repetition, which serves picture book narrations so well in storytimes, does double duty here as a means of drilling home how Ando had to persevere in his vision, even when things got tough. Wang follows that old bit of writing advice, show don’t tell. At no point does she ever turn to the reader and say, “And that’s why it pays to be persistent, kids.” She doesn’t have to. Ando’s tale speaks for itself.

If there was an award to bestow upon a picture book for Best Title Page Spread, you know I’d be lining up to cast my ballot with Magic Ramen. The book begins with cheery endpapers featuring cooking oil, flour, eggs, woks, etc. Turn the page and a very different sight meets your eyes. Before you lies a devastated post-WWII Japan. Most of the houses are rubble and wreckage. Makeshift structures dot the landscape here and there, and your eyes are drawn to the little pinpricks of light coming from various windows and burning oil drums. Everything is gray and bleak and obliterated. In this way, Urbanowicz is doing what a great informational illustrator should always strive to do. She is setting the stage, and advancing the plot. Without really feeling what it was like to see Japan at this point, you wouldn’t be able to grasp Momofuku Ando’s burning certainty that there was something he could do to help people. In fact, the first time you even see a well-lit scene, it’s a two-page spread of people waiting in line for a bowl of ramen. The brightest source of light comes from that large ramen bowl, while all around people’s breath puff out into the cold night air. The connection is clear. Ramen isn’t just the food these people need and crave. It’s light and life and a path out of the destruction. All this told without a word.

Artist Kana Urbanowicz lives in Kanagawa, Japan, which helps to lend the book a look of authenticity. Insofar as I can determine, these seems to be her first book here in the States, and she is long overdue. That first double page title spread is so dark and devastating that it doesn’t prepare you for what is, essentially, a pretty light and bouncy story. Urbanowicz utilizes a drawing style that has certainly been influenced by manga, but doesn’t adhere wholly to the form. I was particularly taken with the ways in which she chose to break up the images on the pages. She handles the layouts like an old pro. You might get a page split in half vertically, showing Ando’s process, facing another page in which the images are split in half horizontally to the same end. And what does her page of Ando’s victory look like? Well, the man doesn’t look all that different, holding up his bowl of ramen in triumph, but the artist places his studio against blooming cherry blossoms, giving everything a beautiful cast of pinks and purples. A book that is a pleasure to look at, as well as a pleasure to read, is a privilege.

If the book has a flaw it may lie in the endpapers. Wang takes a distinctly European attitude towards backmatter in a work of nonfiction. Which is to say, there’s not much there. No timeline, no glossary, no Bibliography or list of sources, none of that. There is an Author’s Note on Japanese surnames, a Pronunciation Guide, and an Afterword that contains pretty cool information, like that the first astronaut to eat ramen in space was Soichi Noguchi in 2005, or that ramen is given out to hungry people left homeless “through earthquakes, hurricanes, wars, and other calamities.” Alas, for some it will not be enough. Some teachers require that biographies cite their sources. Even so, I would give Magic Ramen extra points for failing to fall into the “fake dialogue” trap. So many works of picture book nonfiction fail to have the courage of their convictions and will fill their pages with words that were never said. Not ONCE does Wang ever do this, and the end result is a book more accurate than scores of other titles with fancy Timelines and Sources.

Magic Ramen, for me, is the kind of book that can bridge that gap between kids that like fact and kids that like fiction. Luring fiction readers over to the world of informational texts is one of my great pleasures in life. It isn’t all that hard, if the book is interesting enough, the text fun, and the subject original. This is the book that can convince a child that real life is just as full of kooky stories as anything you could make up. So here’s to the little bio unafraid to try something new. And, unlike Momofuku Ando, it gets it right on the very first try.

On shelves now.

Source: Final copy sent from publisher for review.

Like This? Then Try:

- Chef Roy Choi and the Street Food Remix by Jacqueline Briggs Martin and June Jo Lee, ill. Man One

- How the Cookie Crumbled: The True (and Not-So-True) Stories of the Invention of the Chocolate Chip Cookie by Gilbert Ford

- Mr. Crum’s Potato Predicament by Anne Renaud, ill. Felicita Sala

Filed under: Best Books, Best Books of 2019, Reviews, Reviews 2019

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

One Star Review, Guess Who? (#211)

Kevin McCloskey on ‘Lefty’ | Review and Drawn Response

Notable NON-Newbery Winners: Waiting for Gold?

The Seven Bills That Will Safeguard the Future of School Librarianship

Take Five: Newbery Picks, Part Two

Gayle Forman Visits The Yarn!

ADVERTISEMENT

Thank you. I was looking at this for my library, but was undecided. This sealed the deal. Also, fitting that today I brought ramen for lunch.

A group of librarians at my location all went out for a ramen lunch after reading this. It sort of forced our hand.

It’s a terrific book! I’m so glad you focused the spotlight on Andrea’s book.

Speaking of the Chocolate Chip Cookie book, did you know tomorrow is National Chocolate Chip Cookie Day?

https://www.cmlibrary.org/blog/summer-diets-aside-national-chocolate-chip-cookie-day-august-4

There is a charming movie, The Ramen Girl, about an American in Japan learning to make ramen.

I’m eager to read this book; the pictures look dramatic and funny at the same time, full of incredible detail. I do have to raise a reservation. It is very important to me that books about history be historically accurate. I looked up some information about Momofuku Ando’s life. He was Chinese, from Taiwan, but lived in Japan throughout World War II. I am always suspicious when the years of that war are absent from biographical material. I found only one reference, on The Guardian,which claimed that he had avoided military service, something which was really difficult to do in fascist Japan. From what I can see of the book online, there are descriptions of post-War poverty and hunger, inspiring Ando to develop his new food. What events led to that suffering? It’s misleading to kids to present his invention in a vacuum, as if some bad forces had intervened to deliberately cause this situation.(A page on Google images shows this sentence: “A long line of people wound down the street. It was winter and they shivered in their ragged clothes.”) Of course, I intend to read the book before judging it definitively, but I would be worried that kids reading it might have a grossly inaccurate idea of what exactly had caused these difficult conditions in Japan.

Having read it, I thought the acknowledgement that this was post-war Japan was pretty clear. Do you need the historical ramification of the reasons behind the inciting incident that caused Ando to research food that could serve starving populations? I think you could argue it either way. If the focus of the book were to remain in the immediate post-War time period then I’d say yes, you should give more background. But that section lasts four pages, mentions the war, and I think kids will get the impression that war causes poverty more than anything else. Not an inaccurate generalization to make. I encourage you to read the whole thing, though, and see what you think. More backmatter would have made me happy.

Of course, I will read the whole book. So far, I love the pictures, and everybody loves ramen noodles. I have written before about my concern that, the farther away an event recedes into the past, the more people feel license to paper it over, or at least to forget the more unpalatable parts. (I had much more serious issues with Thirty Minutes Over Oregon, which I felt was completely predicated on a trivializing of atrocities in order to promote a false and anachronistic sense of reconciliation.) I understand that the War itself is a small part of this book, but, then again, it seems that the whole invention of ramen grew out of the post-War experience of deprivation. So to me, the causes of that deprivation are pretty important. The author could have included it in the backmatter, or she could have introduced the post-War period of shortages as the unfortunate but inevitable result of a military dictatorship. War causes poverty, but many different reasons cause war. In this case, it was brutal aggression on the part of the Axis powers which led to worldwide suffering.

I read this to a group of 2nd/3rd graders yesterday, and they liked it. One kid noticed that nobody was wearing shoes on the spread where they’re all making ramen in the kitchen. That led to a whole discussion about how in Asia people don’t wear shoes indoors, and why not, and how some people in this country have also decided that not wearing shoes in their house is a good idea. It took the discussion of the book in a completely unexpected direction, but just shows why we read books!