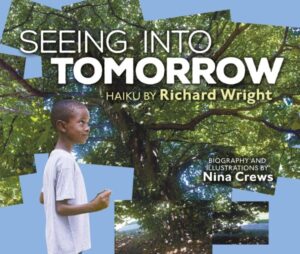

Review of the Day: Seeing Into Tomorrow by Richard Wright and Nina Crews

Seeing Into Tomorrow

Seeing Into Tomorrow

Haiku by Richard Wright

Biography and illustrations by Nina Crews

Millbrook Press (a division of Lerner)

$19.99

ISBN: 978-1-5124-1865-1

Ages 6-10

On shelves now

I hate that phrase, “A picture’s worth a thousand words”. It’s trite. Simplistic. And horrendously true. Pictures have power. Take the story that’s been handed to us about African-Americans for decades. The images that appear in our news all tell stories of black violence, crime, and poverty. Stories that people buy into because, after all, can’t you believe your eyes? Children’s books could be a respite from that kind of misrepresentation were it not for the fact that they’re often little better. If you’re a black boy looking for some kind of representation in your books of brown-skinned American boys that aren’t (A) Slaves (B) Former slaves or (C) Living during the Civil Rights Era, good luck to you. And photographs? I mean, finding children’s books with photos to begin with is hard these days. Oh, there was a time back in the 50s and 60s when you might find a book like J.T. by Jane Wagner and Gordon Parks Jr., but in spite of the fact that the printing costs of photos in picture books is cheaper than ever, the publishing industry generally treats photography as an embarrassing art form that’s only good for accompanying nonfiction texts. Enter Nina Crews, one of the few photographers working today that regularly includes photographic images of contemporary black kids in her children’s books. She’s paired her work with poetry in the past, though it’s usually of the nursery rhyme variety. Now with Seeing Into Tomorrow she tries something new. The haikus of the great author Richard Wright are paired with image after image of black boys running, walking, riding, and just generally staring into a natural world that is this close to showing them the future. A tomorrow that we would all like to see more of.

It’s becoming a good year for the great African-American writers of the 20th century. James Baldwin’s only book for children Little Man, Little Man is being reprinted, there’s a novel of a boy discovering the world of Langston Hughes in Finding Langston by Lesa Cline-Ransome on the horizon, and now Richard Wright has his very first collection of haikus in a form for young readers. Originally published after his death in 1998 in the collection Haiku: This Other World, Nina Crews has selected a svelte twelve from a possible four thousand. With each poem she constructs squares of photographed images of nature. Forests rise, skies are pieced together, and the poems are featured alongside brown boys that help to embody everything Wright is implying. A brief biography of Richard Wright appears at the back of the book alongside A Note On the Illustrations and well-curated suggestions for Further Reading.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Let’s head off at the pass the whole “what is haiku?” question right here and now, if we can. As far as I can ascertain, there are several ways to tackle that question. You’ve got the folks that adhere to the strict 5-7-5 syllable style, and do not think much about the subject matter. Then you have the folks that point out that the 5-7-5 style is a Western construct. In fact some children’s books (like Jon J. Muth’s Hi, Koo) don’t adhere to it at all. Then there’s the subject matter, which, in traditional haiku focuses on nature and how we, as humans, relate to it. In the case of this particular book, Mr. Wright adheres to the 5-7-5 format and he also makes certain that even a poem about the railroad feels a part of nature (after all, trains are experienced by most folks in an outdoor setting). Ms. Crews for her part has selected a wide variety of types of nature, all the better to accompany with her images.

Let’s head off at the pass the whole “what is haiku?” question right here and now, if we can. As far as I can ascertain, there are several ways to tackle that question. You’ve got the folks that adhere to the strict 5-7-5 syllable style, and do not think much about the subject matter. Then you have the folks that point out that the 5-7-5 style is a Western construct. In fact some children’s books (like Jon J. Muth’s Hi, Koo) don’t adhere to it at all. Then there’s the subject matter, which, in traditional haiku focuses on nature and how we, as humans, relate to it. In the case of this particular book, Mr. Wright adheres to the 5-7-5 format and he also makes certain that even a poem about the railroad feels a part of nature (after all, trains are experienced by most folks in an outdoor setting). Ms. Crews for her part has selected a wide variety of types of nature, all the better to accompany with her images.

Out of curiosity, I wanted to see if anyone had ever collected Wright’s haikus for kids before. To my astonishment (or was it sadness?) I found that anytime Wright’s haiku comes up in a children’s book, he’s just one of many poets in an anthology. There was the National Geographic Book of Nature Poetry, Firefly July, African American Poetry (the one edited by Arnold Rampersad and Marcellus Blount), and a few others. Good books, sure and certainly, but why has no one ever rated Wright’s haikus worthy on their own merits for young readers? Why indeed. Perhaps no one felt equal to the task. Haiku, after all, is difficult to display in a children’s book format unless you know how to tackle the material in an interesting way. And photographs are, to my mind, mighty interesting.

Years ago I organized a panel of photographers working in the field of children’s literature. And, since this was New York after all, I had to make sure that Nina Crews was included. You simply can’t think of artists that illustrate children’s books with photographs (or can you even call it “illustration” at all?) without thinking of Ms. Crews. She was one of the first artists unafraid of Photoshop, producing books like The Neighborhood Mother Goose, working with large publishers. I always enjoyed her work, but I felt like I was waiting for something. Something on a grander scale or something. Turns out, I was waiting for Seeing Into Tomorrow. Because it isn’t just her selection of the twelve Wright poems that deserves notice. Look how she’s changed her own style to match. First off, there’s the fact that she’s placing her subjects in nature. Because she lives in Brooklyn, so much of Ms. Crews’ work has been set in the city. And, to be honest, it still is sometimes. If I’m not much mistaken the poem of the boy walking the dog looks an awful lot like Prospect Park.

Years ago I organized a panel of photographers working in the field of children’s literature. And, since this was New York after all, I had to make sure that Nina Crews was included. You simply can’t think of artists that illustrate children’s books with photographs (or can you even call it “illustration” at all?) without thinking of Ms. Crews. She was one of the first artists unafraid of Photoshop, producing books like The Neighborhood Mother Goose, working with large publishers. I always enjoyed her work, but I felt like I was waiting for something. Something on a grander scale or something. Turns out, I was waiting for Seeing Into Tomorrow. Because it isn’t just her selection of the twelve Wright poems that deserves notice. Look how she’s changed her own style to match. First off, there’s the fact that she’s placing her subjects in nature. Because she lives in Brooklyn, so much of Ms. Crews’ work has been set in the city. And, to be honest, it still is sometimes. If I’m not much mistaken the poem of the boy walking the dog looks an awful lot like Prospect Park.

Still, there are true moments of nature beyond the borders of NYC. Her Photoshop work has grown more natural over the years. But most interesting to me was how the backgrounds are cut into overlapping squares and rectangles. I thought long and hard about why she chose to illustrate the book in this way. Then I noticed how well the haikus fit into the blank spaces inside or beside or under the photographs. Haiku, should anyone ask, is supremely difficult to make visually interesting. I’ve seen librarians discount haiku collections where the design overwhelmed the subject matter. Not so here. Here, the font is large and the presentation cool and clear and calming. As for the photos, what could come off as disjointed instead becomes an extension of nature itself. The boys featured here are both part and not part of the backgrounds. And why just black boys? As she explains in her “Note On the Illustrations”, after learning about Mr. Wright’s own youth, she wanted, “the reader to imagine the world through a young brown boy’s eyes. A boy, like Richard Wright, who found wonder in the world around him.”

There is also the occasional in-joke for die-hard children’s literature fans. It was my co-worker who pointed out to me what was going on with one particular poem. The text reads, “Empty railroad tracks: / A strain sounds in the spring hills / And the rails leap with life.” The picture features a freight train coming from wooded hills while a boy and his grandfather watch. I don’t suppose it ever occurred to me to wonder who that older man might be. I had forgotten that Nina Crews is part of a longstanding children’s book legacy. Her mother was Ann Jonas, perhaps best known for the picture book Round Trip. Her father? None other than Donald Crews, the genius behind that picture book / board book standard Freight Train. And there he is in this photograph, big as life, with Nina’s own son, watching a real life freight train chugging on past.

There is also the occasional in-joke for die-hard children’s literature fans. It was my co-worker who pointed out to me what was going on with one particular poem. The text reads, “Empty railroad tracks: / A strain sounds in the spring hills / And the rails leap with life.” The picture features a freight train coming from wooded hills while a boy and his grandfather watch. I don’t suppose it ever occurred to me to wonder who that older man might be. I had forgotten that Nina Crews is part of a longstanding children’s book legacy. Her mother was Ann Jonas, perhaps best known for the picture book Round Trip. Her father? None other than Donald Crews, the genius behind that picture book / board book standard Freight Train. And there he is in this photograph, big as life, with Nina’s own son, watching a real life freight train chugging on past.

I’m trying to think of books to compare this one to. Trying to think of books about black boys that give them their proper due. A couple years ago I tried counting all the middle grade novels about African-American boys printed in a given year. I came up with five. That number’s slightly higher these days, but black boy pride is still too rare. Maybe things are looking up, though. Last year the Derrick Barnes/Gordon C. James picture book Crown: Ode to a Fresh Cut won a Caldecott Honor and a Newbery Honor. This year Tony Medina’s 13 Ways of Looking at a Black Boy (another book of poetry) is getting rave reviews. With Seeing Into Tomorrow these books make a trifecta. It’s not enough. Let’s fill the shelves with strong black boy characters. Let’s make them so prevalent and common that people start arguing with one another over which one is their favorite. And to start? Let’s read Seeing Into Tomorrow. A book with a foot in the past and a strong future ahead of it.

On shelves now.

Source: Copy borrowed from the library for review.

Like This? Then Try:

- 13 Ways of Looking at a Black Boy by Tony Medina

- Crown: Ode to a Fresh Cut by Derrick Barnes

Interviews:

- Nina sat down with James Preller to answer 5 Questions about the book.

- And this is neat. Nina sat down with the folks behind Can I Touch Your Hair? to talk about the commonalities between their books in this conversation.

- And Seven Impossible Things Before Breakfast spoke with her at Kirkus here.

Video:

Here’s an interview with Nina where she explains even more about the book:

Filed under: Best Books, Best Books of 2018, Reviews, Reviews 2018

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

One Star Review, Guess Who? (#202)

Exclusive: Giant Magical Otters Invade New Hex Vet Graphic Novel | News

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

Take Five: LGBTQIA+ Middle Grade Novels

ADVERTISEMENT