Review of the Day: The Miscalculations of Lightning Girl by Stacy McAnulty

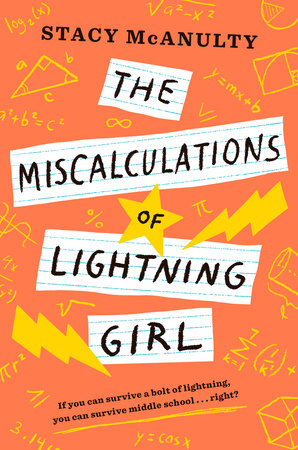

The Miscalculations of Lightning Girl

The Miscalculations of Lightning Girl

By Stacy McAnulty

Random House Books for Young Readers

$16.99

ISBN: 9781524767570

Ages 9-12

On shelves now

The world would have us believe that the left brained and right brained amongst us can never see eye-to-eye. Think about it. How many times have you heard a perfectly intelligent person say with a shrug, “I’m bad at math”? This is considered acceptable behavior amongst the literary. In fact, the sentence might, at most, elicit some sympathetic shrugs from listeners. Now imagine the person saying, “I’m bad at reading”. Disbelieving laughter might come, following by stunned silence. Why do we feel this way? Because at a young age the speaker, as a child, was probably victim of a bad math experience or (and this is very likely) heard a respected grown-up say those very words “I’m bad at math” and internalized them. I mean, truly, some folks just aren’t good at it because their brains don’t operate that way, but there’s a whole swath of people that don’t suffer that same problem. Where’s their literature? Who are their heroes? And while I admit that writing a novel about a math lover is taking a left-brain issue and planting it squarely in right-brain territory, I’m also truly grateful this book exists.

You know how your parents tell you not to go swimming during a lightning storm? Apparently no one ever told Lucy not to go climbing any chain link fences either. One minute she’s a normal 8-year-old and the next she’s been struck by lightning. The good news is that she survived it. The odd news is that it gave her superpowers. Okay, not really. She got left with a lot of neuroses and maybe some obsessive-compulsive disorders, but there was one upside. Lucy is now a certifiable math genius. Heck, she’s already passed the GED at home. With that taken care of, Lucy is ready to apply to all the best colleges. There’s only one snag in the plan – Nana. Nana is convinced that Lucy needs some socialization, so the next thing she knows she’s being packed off to the local middle school. As expected, it’s awful, but there are a couple silver linings. There’s Windy, the social activist with a big mouth that takes Lucy under her wing. There’s also Levi, the cynical photographer who can keep a secret. Math is easy for Lucy. Middle school is hard, friendships (and betrayals) harder, and ultimately deciding to stay or to go? That may turn out to be the most difficult problem of all.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

So let’s consider the wide and wonderful world of math in children’s novels. When I mention it, what books come immediately to mind? Maybe The Phantom Tollbooth or Flatland. Maybe The Number Devil or Gene Luen Yang’s Secret Coders series. You can’t think of all that many off the top of your head, though, can you? After a while you start asking yourself questions like “Does Alice Through the Looking Glass count?” I’ve seen plenty of novels seem to include math, but if the main character likes it then it’s usually played off as a quirk. For example, in Giant Pumpkin Suite, by Melanie Heuiser Hill, the main character’s math is present right at the start and then just sort of alluded to for the rest of the book. This is what makes Lightning Girl so extraordinary. As an author, McAnulty doesn’t skimp on the math. Nor does Lucy forget about it in the course of the story. Math is so integral to her being that it provides the answer on how to do the group project. It distances her from her friends. And at the end of the book we even have a section on Pi and another on Fibonacci. McAnulty is committing to the bit.

Disability is not a substitute for a personality. I’ve read countless novels where a character is solely defined by what makes them different. It can be a key component, absolutely, but if you make it all there is to know about the person then you find yourself in tricky territory. Boring territory, frankly. At the end of the book Lucy says, with a hint of surprise, “I’m more than just numbers”. Had the author done a poor job of bringing her to life, the reader might disagree with that little closing statement. Instead, you find yourself nodding a little. Lucy will never escape her accident. Not really. But she can still choose the kind of person she wants to be. And it’s because of her author that we, the readers, feel she’s capable of doing so.

As I read through the book, it was easy, as a 21st century adult, to identify many of Lucy’s quirks as a form of OCD. Why does no one else in the books, with the exception of Windy, seem to know about this? I took a step back. One important thing to remember is that even if we’re living in a world where people know what OCD is, that knowledge doesn’t mean they know what to do about it. Or how to handle it. Or how to explain it to classmates. The incompetence of real adults is always going to pave the way for the incompetence of literary adults. It’s all very believable, even if you wish it wasn’t.

There were other choices in the book that I found myself appreciating. Take how McAnulty writes characters. In this tale Lucy acquires two new friends. Friendships of three people tend to be very strong in children’s books. Just think of Ron, Harry, and Hermione. How do you create a trio without inadvertently referencing that classic threesome? Easy peasy, you just make sure that one of the trio is a cynic, the other a cock-eyed optimist, and the third a complete newbie to friendships in general. Or, as Windy tells Lucy at one point, “You don’t try to change people. It’s like you’re only trying to understand people.” Then there’s the bully. In many ways, Maddie is a pretty standard bully material. Disliking the hero from the get-go? Check. Hangers-on? Check. But even as she ratchets up the pain, McAnulty grants her moments of humanity, like when she gives Levi some money to buy himself a new lunch. She is awful, though. And after one of the more satisfying bully comeuppance moments in children’s literature, the author still does the standard it’s-not-okay follow-up to the moment but, c’mon. Still awesome.

Do you ever find yourself in a situation where you encounter an author that you honestly believe you’ve never read before, only to find that they’re the mild-mannered genius behind some of your favorite books? Man, I’ve been all over McAnulty’s new picture book Max Explains Everything (the single greatest breakdown of grocery store shopping you’ll find), little suspecting that the author was also behind Lightning Girl. This may be her debut novel but the woman knows how to write. In many ways this is just your usual fish-out-of-water middle school tale. But throw in all that math (she doesn’t skimp on the numbers), the character development, and the writing itself (a good dose of humor never hurts anything) and you’ve got yourself one heck of a fun, strong book. It doesn’t matter if the kids reading this thing like math or loathe it. It’s hard to resist a heroine (and a book) packed to the gills with electricity. This book? It’s number one.

On shelves now.

Source: Galley sent from publisher for review.

Filed under: Best Books, Best Books of 2018, Reviews, Reviews 2018

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

The Moral Dilemma of THE MONSTER AT THE END OF THIS BOOK

K is in Trouble | Review

Fighting Public School Book Bans with the Civil Rights Act

ADVERTISEMENT