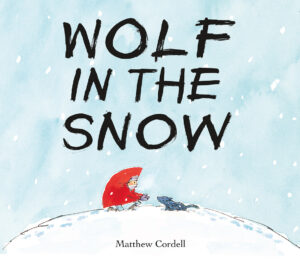

Review of the Day: Wolf in the Snow by Matthew Cordell

Wolf in the Snow

Wolf in the Snow

By Matthew Cordell

Feiwel and Friends (an imprint of Macmillan)

$17.99

ISBN: 978-1250076366

Ages 4-7

On shelves now

It’s hard to pinpoint exactly why it is that I love picture books as much as I do. Putting aside the usual reasons (brain growth, increasing a child’s capacity for wonder, parent/child bonding, and so on, and so forth) on a purely personal level I think what draws me to them time and again is that the form is so open to artistic expression and change. Unless it’s a sequel (or written by a celebrity, for that matter), every single picture book out there is an object that must stand or fall entirely on its own merits. An author or illustrator that has experienced success in the past is naturally going to incline towards the safe option of producing more of the same. If and when they stretch beyond their comfort zone into uncharted territory, that is the moment I prick up my ears and dust off the old eyeballs. Let us take artist Matthew Cordell as today’s example. Prolific? Baby, you don’t know the half of it. A mere glance at the number of books he’s illustrated in as short a time as he’s done it leaves a mere mortal wondering how such proliferation is even possible. But Cordell’s is a simple drawing style. A child-friendly series of pen and inks with watercolors. At no point would I have suspected him capable of the pinpointed shocks of realism that you get when you read his solo project, Wolf in the Snow. A clever mélange of wolf tropes, heartfelt storytelling, and a call for conservation so understated you could blink and miss it, the greatest praise I can heap upon this book is to say that it reminds me why I love picture books as much as I do; they’re constantly surprising me.

One girl, alone. She wears a red coat with a pointed hood, and in the light flurries of winter she traipses off to her school in the countryside. On the way home the snow begins to fall in earnest. Meanwhile, a wolf pack is making its way across the land. Its youngest member, a small cub, falls behind and becomes lost in a whiteout. When the girl crosses paths with the wolf she takes it in hand. It can’t walk in the drifts, so she bears it over streams, past hostile raccoons and owls, finally to its mother. The walk and weight of the cub has taken its toll on the girl, though. Unable to walk further she huddles into a ball. Fortunately, the pack surrounds her and through their howling they are able to call her family dog and her mother. Mothers and their children, one and all, reunited again.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

One of the most interesting aspects of the book is Cordell’s willingness to play with the child reader’s built-in expectations. If a girl wears a red hooded outfit and wolves are seen on the periphery then the likelihood that this girl is going to get eaten is pretty darn high. Now I’ve been wracking my brain, trying to come up with another book where the images are cartoonish while the animal threat is not. The closest thing I could think of was Neil Gaiman and Dave McKean’s The Wolves in the Walls. Like this book, there’s an honest shock when, in the midst of pure, silly illustration, you get these hyper-realistic pen-and-ink wolves emerging from the very walls. But where Gaiman and McKean used that moment for shock value, Cordell’s first look at a realistic wolf is ambiguous. My 2-year-old son, fed on a steady diet of fairy tales, knew from prior Three Pigs/Red Riding Hood experience that wolves are not good news and felt free to tell me as much. Yet these wolves, while nodding to their fairy tale antecedents, are also freeing kids from wolf-based prejudices. Cordell is leading you into the tale with a fairy tale premise, but when all is said and done he’s actually made a quiet case for conservation by the story’s end. Little wonder that he name checks the Yellowstone Wolf Project in his Acknowledgments at the story’s start.

As for the art itself, it’s so interesting to read and reread and reread again this book. You’d think that a nearly wordless story wouldn’t yield much in the rereadings unless it was chock full of tiny details or something. Cordell does have little details that reward closer examinations (the mom always wears green and the dad yellow, the wolf statue on the mantelpiece, etc.) but the real reason I like reading this book so many times is in how he conveys expression and emotion. For most of the book all you can see of the girl’s face are her eyes. A scarf is wrapped tightly around her mouth, so Cordell has seemingly, and with full knowledge of doing so, limited his heroine’s range of expression. Yet every feeling courses across her face beautifully. We see her exhaustion, her fears, her relief, and her bravery. We can also admire the ways in which Cordell can create water vapor in the air out of watercolors, or the muted pink of a setting sun behind a cloudy sky. The sole image in this book I had a problem with was of the wolf cub’s face when the girl reaches out to him, the first time, in supplication. A horizontal black slash below the eye makes it look like he simultaneously has his eyes both open and closed. I know the open eye is the one I’m supposed to be tracking, but that slash throws me off every single time. Otherwise, no objects from the peanut gallery over here.

As for the art itself, it’s so interesting to read and reread and reread again this book. You’d think that a nearly wordless story wouldn’t yield much in the rereadings unless it was chock full of tiny details or something. Cordell does have little details that reward closer examinations (the mom always wears green and the dad yellow, the wolf statue on the mantelpiece, etc.) but the real reason I like reading this book so many times is in how he conveys expression and emotion. For most of the book all you can see of the girl’s face are her eyes. A scarf is wrapped tightly around her mouth, so Cordell has seemingly, and with full knowledge of doing so, limited his heroine’s range of expression. Yet every feeling courses across her face beautifully. We see her exhaustion, her fears, her relief, and her bravery. We can also admire the ways in which Cordell can create water vapor in the air out of watercolors, or the muted pink of a setting sun behind a cloudy sky. The sole image in this book I had a problem with was of the wolf cub’s face when the girl reaches out to him, the first time, in supplication. A horizontal black slash below the eye makes it look like he simultaneously has his eyes both open and closed. I know the open eye is the one I’m supposed to be tracking, but that slash throws me off every single time. Otherwise, no objects from the peanut gallery over here.

Children’s book reviewers are prone to over-exaggeration and I am not innocent of this crime. I squee as loudly as anybody. I employ overused phrases like “the best” and “awesome” and “if you read only one book…” I even make occasional comparisons to the gods and goddesses of the field, so I’m going to preface what I’m about to say with a small explanation. I am about to invoke the name of Maurice Sendak. There is no Sendakian children’s author at work today. Not if we are to take into account the breadth and the depth and the sorrow and the humanity of his work. However, in his early years Sendak had a fine eye for page design and in this respect Matthew Cordell follows squarely in Mr. Sendak’s footsteps. Consider the book Where the Wild Things Are. As you read through that book you watch the margins. You pay close attention to what happens when images spread to the pages edges or contract into nice, tight squares. Wolf in the Snow is equally fascinating in this respect. I was utterly blown away by the myriad ways in which Cordell seeks to focus the readers’ attention on an individual, a group, or the looming threat of a given situation.

The book opens with a cozy image that, at the same time, takes up a full page. We’re accustomed to opening our picture books so as to meet the title page. Not so here. Cordell sets the stage instantly with a wordless family scene. We are watching this, through a window, from outside in the snow. After a turned page we get another full two-page spread that goes to the edges of the pages, showing the girl waving at her dog as she tromps off to school. Cordell is taking us from a cozy interior to a land with wide-open sky. A sky that could, potentially, cause that little girl some trouble. Now turn the page and look at what he’s done. The girl is now enclosed on the left-hand page in a tight bubble. On the opposite page, the wolf page is in its own bubble, but he’s set it up so that it seems that in spite of the miles between them, these wolves and this girl are inevitably going to meet. That’s when he finally let’s you have you precious title page, and none of the characters are anywhere to be seen. Just sky and snow. Snow and sky. From this point on the pages bleed to the edges, only to contract into those aforementioned bubbles as the girl and the wolf pup grow nearer and nearer to one another or when the girl confronts the wolf’s mother. And while Cordell does use panels on occasion for the sake of narrative brevity, for the most part he keeps his images big and bold and full-page.

The book opens with a cozy image that, at the same time, takes up a full page. We’re accustomed to opening our picture books so as to meet the title page. Not so here. Cordell sets the stage instantly with a wordless family scene. We are watching this, through a window, from outside in the snow. After a turned page we get another full two-page spread that goes to the edges of the pages, showing the girl waving at her dog as she tromps off to school. Cordell is taking us from a cozy interior to a land with wide-open sky. A sky that could, potentially, cause that little girl some trouble. Now turn the page and look at what he’s done. The girl is now enclosed on the left-hand page in a tight bubble. On the opposite page, the wolf page is in its own bubble, but he’s set it up so that it seems that in spite of the miles between them, these wolves and this girl are inevitably going to meet. That’s when he finally let’s you have you precious title page, and none of the characters are anywhere to be seen. Just sky and snow. Snow and sky. From this point on the pages bleed to the edges, only to contract into those aforementioned bubbles as the girl and the wolf pup grow nearer and nearer to one another or when the girl confronts the wolf’s mother. And while Cordell does use panels on occasion for the sake of narrative brevity, for the most part he keeps his images big and bold and full-page.

Snow and wordless books go together like hot chocolate and marshmallows. Just off the top of my head there’s The Snowman by Raymond Briggs and The Only Child by Guojing, but look into it sometime. There’s something about a snowfall that gives you a newfound respect for the silent form. Admittedly Mr. Cordell’s book is not wholly wordless. But it is the animals that are allowed to speak in this book. Not the humans. No one reading this book would want there to be any text, though. I’ve read some wordless books that require additional explanation from the parental units reading them. This book is commendable for its clarity. Everything makes sense, even if the characters don’t always do what you think they would.

And now, a moment of silence (no pun intended) for the cover hidden beneath Wolf in the Snow’s book jacket. Many is the library that will Mylar that cover in a thick plastic sheath and tape it soundly to the book inside. If they do, loads of children will miss that fact that under the cover is an entire photo album of the two main characters. On the front cover you have the girl and her parents. It is, actually, the only time in the book that you can see her not wearing her customary red coat. On the back cover is the wolf cub and its family. There is even a moment of true affection between the cub and its mother, unseen in the book itself. Whether these picture take place before or after the events in the book is difficult to say. I’m just grateful they exist at all.

If you were to describe this book in the simplest terms possible you’d just say it was a book of, as Kirkus put it, “kindness repaid.” And it is. Kids see quite clearly that the girl’s good deed has a direct correlation to the wolves’ subsequent generosity. But I’d also argue that the book has a lot more going on below the surface. This is a book the celebrates the art of picture book storytelling in a very pure form. It’s a book that reminds us that when characters walk through thick, white, falling snow, they are somewhat obliterated by all that whiteness. The page underneath is white too. Wolf in the Snow is a quest story, albeit a truncated one. It’s also a tale about mothers and their children and the comforts of home. Or, as I said before, it’s a book that reminds you why we should all be grateful that picture books even exist. Practical, artistic, original, experimental, and ultimately hopeful. If wolves and humans can get along this well, maybe there’s hope for us all.

On shelves now.

Source: Final copy sent from publisher for review.

Like This? Then Try:

- Brave Irene by William Steig

- Fox’s Garden by Princess Camcam

- The Only Child by Guojing

Professional Reviews:

- A star from Kirkus

- A star from SLJ

- A star from Publishers Weekly

Other Reviews:

Media:

And, naturally, the book trailer as well.

Filed under: Best Books, Best Books of 2017, Reviews, Reviews 2017

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Name That LEGO Book Cover! (#53)

Exclusive: Vol. 2 of The Weirn Books Is Coming in October | News

Fighting Public School Book Bans with the Civil Rights Act

Take Five: Middle Grade Anthologies and Short Story Collections

ADVERTISEMENT