Interview with Lynne Jonell: Cats, Rats, and Squishing Machines

Folks, one of the things I love about this job is the fact that I get to watch authors’ careers bloom and blossom. I see authors starting out or at the beginning of their careers and watch as they garner praise and flourishes throughout the years. Today’s example is author Lynne Jonell. Back in 2007 I very much enjoyed her book Emmy and the Incredible Shrinking Rat. She’s written so much since then, but her latest is the one that caught my eye. Recently Kirkus said of The Sign of the Cat in a starred review that, “Intriguing, well-drawn characters, evocatively described settings, plenty of action, and touches of humor combine to create an utterly satisfying adventure.” The book follows the adventures of a boy who can communicate with cats. So, right there. You’ve got me. Add in Lynne’s amazing answers to my questions (come for the interview, stay for the reference to a “squishing machine”) and you’ve got yourself a blog post, my friend.

Folks, one of the things I love about this job is the fact that I get to watch authors’ careers bloom and blossom. I see authors starting out or at the beginning of their careers and watch as they garner praise and flourishes throughout the years. Today’s example is author Lynne Jonell. Back in 2007 I very much enjoyed her book Emmy and the Incredible Shrinking Rat. She’s written so much since then, but her latest is the one that caught my eye. Recently Kirkus said of The Sign of the Cat in a starred review that, “Intriguing, well-drawn characters, evocatively described settings, plenty of action, and touches of humor combine to create an utterly satisfying adventure.” The book follows the adventures of a boy who can communicate with cats. So, right there. You’ve got me. Add in Lynne’s amazing answers to my questions (come for the interview, stay for the reference to a “squishing machine”) and you’ve got yourself a blog post, my friend.

Betsy Bird: Hello, Lynne! So let’s just start with the basics from the get go. Where did this book come from? I mean to say, what was the impetus that made you want to write it?

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Lynne Jonell: Hi, Betsy! The first and shallowest impetus for the book was that, back in 2006, I had sent a book off to my publisher but was still in full-steam-ahead writing mode. I wasn’t up for starting a whole new novel just yet, but I thought I could manage a chapter book.

Secondly, as a child, I had always wished I could speak the secret language of animals. Very quickly, a concept took shape—there would be a boy (I had never written about a boy, and it seemed like a new challenge), he could speak Cat (I love cats, plus it seemed that they would be privy to a lot of information—cats go everywhere, and no one worries about whether or not a cat is going to repeat what it hears), and he didn’t know what had happened to his father (every story needs a problem, right? I knew that much.)

Concepts won’t sustain a book for very long, though. For me, there has to be something underneath, some deeper thing that drives me to write a particular story. I usually have no idea what this thing is, or where it is rooted, but I can tell when it is there because I will have an image in my mind—something that haunts me.

When I have a vivid picture—no matter that it makes no sense yet—I know there is power somewhere, there is energy enough for an entire book. Then I will begin to write toward that image. For example, Emmy & the Incredible Shrinking Rat started with a dream of a piece of green paper with a curved line, and later an image of a cane carved with the faces of little girls.

When I have a vivid picture—no matter that it makes no sense yet—I know there is power somewhere, there is energy enough for an entire book. Then I will begin to write toward that image. For example, Emmy & the Incredible Shrinking Rat started with a dream of a piece of green paper with a curved line, and later an image of a cane carved with the faces of little girls.

When I was beginning to toy around with The Sign of the Cat, I saw a boy and a kitten in the sea, struggling to stay afloat as the ship they’d been on sailed away into the night. There was a man on deck of the ship, too. He watched the boy without expression, and he did not give the alarm.

Soon more images began to come—a tiger, a squishing machine, Duncan hiding in a closet and watching with horror as a man dug into a pie—and I couldn’t fit them all into a chapter book. I picked up the story from time to time, playing around with it, but it wasn’t until 2010 that some of the pieces came together and I began to work seriously on the book. Now, of course, I know what the book means to me—and it’s full of personal references—but at the beginning, I didn’t have the faintest idea where it was going.

BB: You’re no stranger to the world of fantasy, but sometimes I feel like you tend to keep one foot rooted in the real world as well. You’re not quite a magical realism writer, but when fantastical elements appear in your books they seem to happen in a world very much like our own. Is there any particular reason for that, do you think?

LJ: Yes, absolutely. My favorite books, as a child, were ones in which magical things happened to ordinary children, going about their ordinary business. Then suddenly—wham! The chemistry set made them invisible, the strange coin they picked up off the street gave them wishes, the nursery carpet turned out to contain the egg of a phoenix, the toy ship purchased in a dark and dusty shop could grow to carry four children, and fly… I loved the idea that maybe, just maybe, it might someday happen to me.

LJ: Yes, absolutely. My favorite books, as a child, were ones in which magical things happened to ordinary children, going about their ordinary business. Then suddenly—wham! The chemistry set made them invisible, the strange coin they picked up off the street gave them wishes, the nursery carpet turned out to contain the egg of a phoenix, the toy ship purchased in a dark and dusty shop could grow to carry four children, and fly… I loved the idea that maybe, just maybe, it might someday happen to me.

Children today may seem more sophisticated than we were, but that’s superficial… deep down, they are developmentally the same, and they believe in the possibility of magic a lot longer than you might think. I have had ten year olds ask me, very shyly, if the magic in my books was real.

That’s why I love to make the world of the book close to the child reader’s world. It seems as if the magic could happen to them, too, someday. And rather than magical realism, perhaps you could call my books “magical science”, because I always base the magic on some scientific concept, to make things even more plausible. For instance, in The Sign of the Cat, I was fascinated with the concept of critical periods of brain development.

There’s a famous study where normal kittens had their eyes covered for a few months after birth. When the covering was removed, the kittens were blind. Their eyes were normal, and there was nothing wrong with the optic nerve, but the connections between the brain and the optic nerve hadn’t been made during a crucial period. There are critical periods with hearing, too, and attachment (think imprinting, with baby ducks), and the acquisition of language.

I thought, what if there’s a critical period where humans had the ability to learn Cat? We wouldn’t know it, because cats can’t be bothered to teach anyone anything, and the chance would go by forever!

BB: What kinds of books did you read when you were a kid? I’m crossing my fingers for the name “Edward Eager” to appear, just so’s you know.

JL: Oh, sure, Edward Eager, of course—but his inspiration was E. Nesbit, and I loved her books even more. The Phoenix and the Carpet, and Five Children and It—masterpieces. I also adored Eleanor Cameron, anything by Ruth Chew (I loved The Wednesday Witch), Hilda Lewis (The Ship That Flew), Bedknobs and Broomsticks, the Narnia books of course, The Hobbit, anything by Elizabeth Enright, Eleanor Estes, Rudyard Kipling; I could go on and on…

JL: Oh, sure, Edward Eager, of course—but his inspiration was E. Nesbit, and I loved her books even more. The Phoenix and the Carpet, and Five Children and It—masterpieces. I also adored Eleanor Cameron, anything by Ruth Chew (I loved The Wednesday Witch), Hilda Lewis (The Ship That Flew), Bedknobs and Broomsticks, the Narnia books of course, The Hobbit, anything by Elizabeth Enright, Eleanor Estes, Rudyard Kipling; I could go on and on…

I also had an abiding fascination with fiction about Native Americans—the different tribes, how they lived, the various cultures. I had a deep and secret longing to go back in time, before European settlers arrived, and be a Dakota boy. I wanted to be a boy because, in the books, they always had the adventures—and I also decided I would have to have perfect vision, because I was terribly nearsighted and I knew I couldn’t steal horses and count coup when I couldn’t see past my nose. I think this period was at its height when I was in fourth grade, and I remember many summer mornings where I’d grab my favorite stick and go off to some vacant lot or field where I would become that Dakota boy for hours on end.

BB: I once ran a children’s bookgroup and held up a new fantasy for them to peruse. One of them groaned audibly when they saw the number on the spine. “No more series!” she cried. I don’t know that that kid was exactly the norm, but she did at least prove to me that there are kids out there that prefer standalone novels to series books. Is The Sign of the Cat a standalone or the first in a series? How did you come to make that decision?

JL: The Sign of the Cat is a stand-alone. I don’t know how that decision was made, actually—it seems that the book made the decision for me. A reviewer said that Cat was a good “series starter” and I wondered where that came from! But I suppose that everyone, when a book ends, likes to wonder what happens next.

BB: Would you call yourself a “cat person”? If so, do you think a non-cat person could ever write a book of this sort?

JL: I’m more a cat person than a dog person. I like the way cats are a little aloof, and don’t slobber all over you with their affection, and aren’t very needy—but they are capable of deep attachment once you get to know them. I like their independence.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

But I don’t own a cat, and I don’t think I needed to be a cat person to write this book. I am most definitely not a rat person, yet I wrote three books about rats!

But I don’t own a cat, and I don’t think I needed to be a cat person to write this book. I am most definitely not a rat person, yet I wrote three books about rats!

BB: If you could speak the language of any kind of animal besides cats, what would it be?

JL: Birds. I would so love to fly… I think they might speak very poetically about flight, and they could come to my windowsill and tell me all about it.

BB: And finally, what are you working on next?

JL: I’m working on a time-travel book based in Scotland. And yes—there was an image with this book, too. The first was a postcard of Castle Menzies. My grandfather, whose clan it was, showed me the picture when I was a child, and I never forgot it.

JL: I’m working on a time-travel book based in Scotland. And yes—there was an image with this book, too. The first was a postcard of Castle Menzies. My grandfather, whose clan it was, showed me the picture when I was a child, and I never forgot it.

The second image came 45 years later; I had a vivid mental picture of an acorn rolling out from a stone wall. I didn’t know what it meant, but I knew that the stone wall was part of the castle, and I also knew that it was time to get to work on that particular book.

BB: Well, many thanks to Ms. Jonell for joining us today. Now about that “squishing machine” . . .

Filed under: Interviews

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

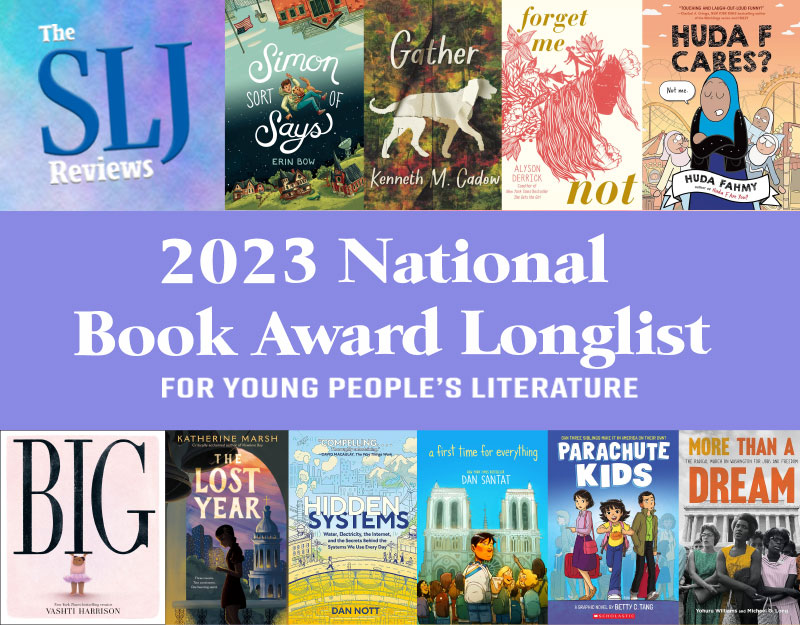

Report: Newberry and Caldecot Awards To Be Determined by A.I.?

Magda, Intergalactic Chef: The Big Tournament | Exclusive Preview

Fifteen early Mock Newbery 2026 Contenders

When Book Bans are a Form of Discrimination, What is the Path to Justice?

Fast Five Author Interview: Naomi Milliner

ADVERTISEMENT